There has been a lot of interest and commentary lately about the Army’s new physical fitness test the Army Combat Fitness Test or ACFT. For the purposes of this article, I will refer to it generically as a Physical Training Test or PT Test for short. Part of what I will be arguing here is that the name of the new test is something of a misnomer. A PT Test – by any name – is not a good standalone gage of the “combat fitness” of an individual or a unit. Indeed, the discussions about the subject on this site and elsewhere on line got me thinking about my personal experiences and observations of successful and unsuccessful physical fitness programs. Visits earlier this year to Fort Benning and last month to Fort Campbell reinforced my own direct experience the last few years I was on active duty. The Army has grown smarter over time about individual fitness and now achieves as good or better results – and with far fewer injuries – than we did in the so-called “good old days” with unit PT centered on long formation runs.

As I considered the subject, I realized that PT Tests and the testing process were never that useful to me as a leader. Certainly, there were a couple of exceptions. Prerequisite testing to get into Ranger School and the SFQC can and does cause anxiety for the candidates and I was no exception. Other than that, in my long career in Infantry and Special Forces “line” units, PT Tests were simply a routine administrative requirement that provided only another data point to indicate if the unit fitness program was working or not. In terms of judging whether my unit was combat ready, PT Tests scores were of little or no relevance. Frankly, in as much as statistics matter, I was a lot more concerned about individual marksmanship scores and in some cases how recently we had completed requalification on infiltration techniques like HALO or SCUBA. Or perhaps how many people I had on hand with advanced skills in demolitions or long range shooting (snipers). Granted, in Special Forces, baseline physical fitness is rarely an issue, but I would say essentially the same thing about the various infantry units I served in over the years.

While we all often use the analogy, combat is not a sporting event or collegial competition.

I agree wholeheartedly that some sports medicine and physical training techniques are applicable to building physical fitness in soldiers. Some extreme sporting events like ultra-marathons might even approach the kinds of physical exertions seen in combat. However, beyond that, the analogy falls apart. NO competition or sanctioned sport I am aware of requires the participant to intentionally and continuously risk death or catastrophic injury. The fear that combat naturally engenders can be debilitating and sap the strength of even the most physically fit – but otherwise unprepared – soldier. Indeed, the physical and especially the psychological demands on soldiers in combat are not analogous to anything an athlete ever faces in a sport. Soldiers have to perform when they are not at their physical peak. They have to function at an acceptable level with little sleep, less than optimum diet and in austere environments and in all weather conditions day in and day out. In other words, sustained combat requires endurance and mental toughness beyond anything that a brief PT test can possibly measure. That is why longer duration stressful programs like Ranger School are considered so valuable a tool in preparing leaders for combat.

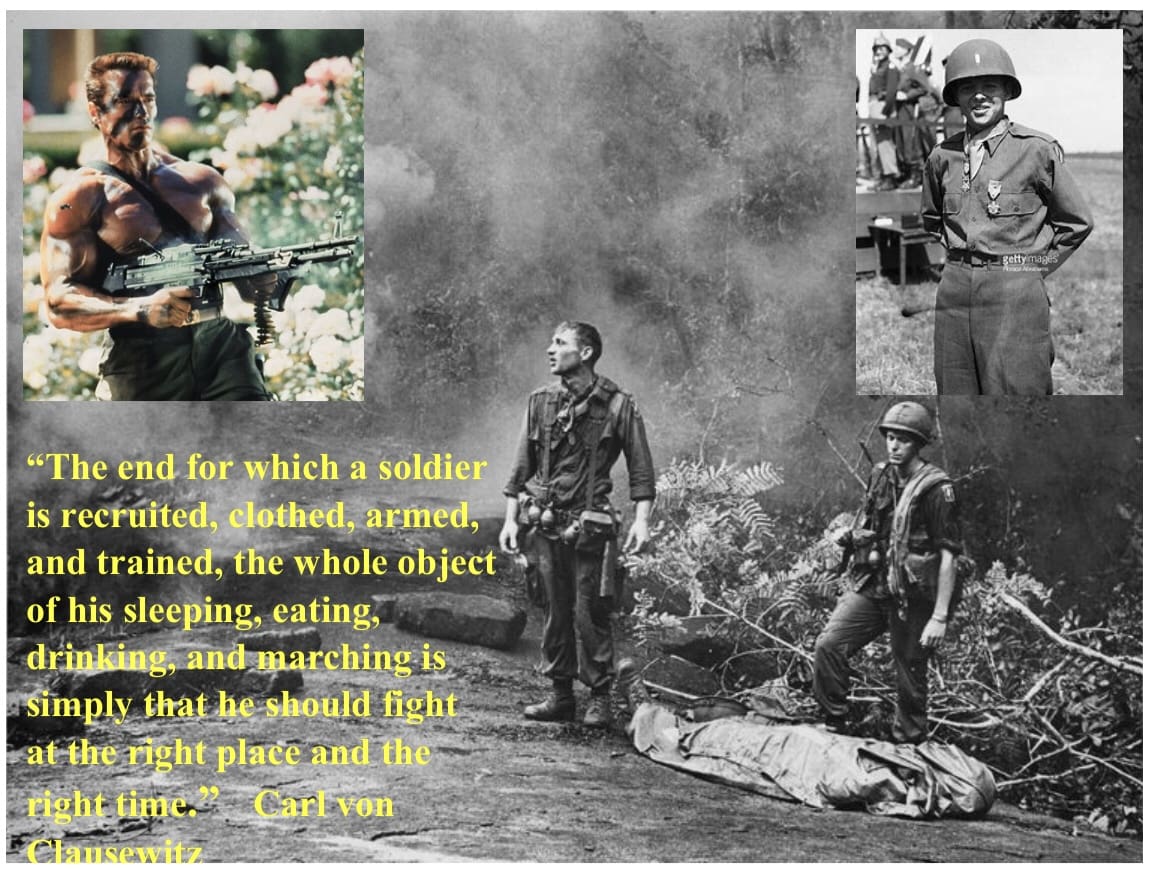

As I have mentioned many times, when I came into the service in 1975, all of my NCOs and the majority of the officers were Vietnam combat vets. Some of the Colonels and CSMs were Korean War vets too. Most of them smoked a lot, and a good many drank way more alcohol than polite society thought acceptable. I am sure those vices reduced their physical fitness by some mathematical factor. Did that really matter? What I do know is that these leaders were exactly the kind of “rough men” that Orwell spoke so eloquently of…and they were nothing if not HARD. Each had been physically and psychologically challenged in the crucible of jungle warfare and had passed the test. Sustained combat is difficult, frustrating, mean and always exhausting. The attached famous picture of members of the 173rd Airborne Brigade speaks to that unforgiving reality. What kind of soldier is best prepared to face that challenge? On the upper left, we have an imaginary commando. He has an impressive physique and the movie is fun to watch but we all know he is play-acting and is not combat ready. Still, because of popular culture that is what many – including some in uniform – think a combat ready soldier should be built like. On the right, we have a short skinny kid named Audie Murphy who was undoubtedly combat ready; this despite the fact that his physique was always unimpressive. That is how many a real combat soldier actually looks. I have no doubt that Arnold Schwarzenegger in his prime could bench press, or dead lift much more weight than Audie Murphy ever could. Nevertheless, if I could choose which one I want at my side in combat it is no contest. I choose Audie Murphy.

I never met Murphy or Schwarzenegger so I am not going to say much more about them. Instead, I am going to talk about some real soldiers I did know. Four in particular that I met while serving in the 1st Bn, 27th Infantry in the 25th Infantry Division in 1982-83. This was before the “Light Infantry” initiative of the mid-80s. In those days, infantry battalions of the 25th were referred to (at least by airborne qualified personnel) as “Straight Leg” or simply “Leg” infantry. This meant that we were not organized to be delivered by parachute and did not have enough organic helicopters to routinely be airlifted into battle. Therefore, we walked everywhere with always too heavy rucksacks on our backs. I am not going to name three of the soldiers in this story because it is not relevant to the points I am trying to make. They were my Battalion Commander, Brigade Commander and a Sergeant (E-5) who worked for me. I was a Staff Sergeant and was leading a Scout Section at the time. The fourth soldier was a SFC (later 1SG) named Jim Myers who was the TOW platoon sergeant in the battalion.

SFC Myers was a friend and mentor of mine and a great professional influence on me. He had joined the Army in 1956 and gone to jump school as a combat engineer at Fort Campbell. After a couple of years, he got out but reenlisted in 1966 to go to Vietnam. He served 4 tours in country with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. He was a short guy and because of his size and previous engineer experience he was routinely called on to do tunnel rat work. He had a picture that was taken as he was crawling out of one of those holes before collapsing it with explosives. In the process, he also earned a couple of Bronze Stars with Vs and four Purple Hearts. My wife and I used to meet up with Jim on Waikiki or one of the other beaches on Oahu on the weekends. So I got to see him with his shirt off many times. On his chest he had one long scar from his right hip up to his left shoulder. There were four distinct bullet holes equidistance along that scar thanks to an AK47 burst he took on his last tour. Not surprisingly, doing pushups and sit-ups was always a struggle for him. Still, he could ruck much younger men into the ground and I swear that if you look up “tough as nails” you will see his picture.

SFC Myers retired in 1988 and passed away about 10 years ago. He was my hero and I wanted SSD readers to meet him. Another positive role model during that time was my Battalion Commander. He had earned two Silver Stars in Vietnam with the 1st Infantry Division. He was a big guy about 6’3” and was a chain smoker as I recall. He had received just one Purple Heart during the war. A mortar shell had landed near him and shredded the muscles in both legs. He apparently had to endure some two years of physical therapy after they put him back together as best they could. His legs remained twisted like warped wood. He walked with a limp and it was painful to watch him run. Yet, he led all the unit road marches – including a three day, 70 miler that we did just before Team Spirit 83. More importantly, he was always out at training actively teaching, coaching, mentoring and leading by example rain or shine. Despite not being what some would consider a PT stud, he was probably the single best infantry battalion commander I ever served with.

On the other hand, my Brigade Commander was almost exactly the opposite. He was tall, tan and fit. However, I never once remember seeing him out at training in the rain or the mud or at night. I never saw him with a rucksack on his back and that is noteworthy in a leg infantry outfit. I learned a lot about bad leadership from him and for that I am grateful. He did have one idiosyncrasy I will highlight here. He liked to run by himself out to unit training on sunny days. He did not like to wear a standard PT uniform on his runs. Instead, he wore ranger panties, running shoes without socks, and – I kid you not – a gold chain around his neck with a silver dollar sized gold medallion. I know all this because he did not wear a shirt but rather a generous coat of coconut tanning lotion slavered over his entire body. Before anyone asks, I have no idea who on his staff was tasked to put the lotion on his back. He would come out, put his hands on his hips, display his toned physique, and grace us lesser men with his presence for a few minutes before running on his merry way. Because of this odd and frankly disturbing habit, he was known in the Brigade un-affectionately as “Disco.”

Sadly, the Brigade Commander had a certain cult following among a few of the junior officers and even some of the junior NCOs. He was young and dynamic and looked like the central casting version of the steely-eyed infantry officer of the movies. My Scout Platoon Leader was one of those guys. It was clear that he idolized the Brigade Commander, saw him as the better professional role model, and was frankly ashamed that the Battalion Commander could not and did not project the same kind of “studly” image. Since he could not differentiate form from substance, the Lieutenant saddled me with a buck sergeant who was a semi-pro bodybuilder. One look at the kid’s guns and the tiny waist and the LT just knew this had to be a superior NCO. Of course the fact that a line company had sent him to us was an obvious clue that they had no use for him. I quickly found out why.

The kid made sure to educate me on his detailed training and dietary requirements. He had to get 8 hours sleep per night and at least an hour at the gym twice a day. He required 5 high protein meals per day that he needed time to prepare himself. Messhall meals or C-Rations were calorically insufficient for his needs. Not to mention that if he was preparing for a competition he would need additional time. Of course, he assured me that he would otherwise be available for unit training. He really said that. I did learn some interesting things about bodybuilding from him and from Schwarzenegger. First and foremost, bodybuilders are not as healthy as one might think from looking at them. They practice unhealthy tricks to make their muscles “pop” like dehydrating themselves before a competition. They train their muscles for show not go and deliberately and severely limiting their fat intake means they have little stamina. They are great for short bursts of activity – say for an hour or less – but flag quickly. This kid could easily max a PT test but literally could not keep up on a road march of several hours even after others took his ruck and weapon.

In short, despite his well-developed muscles, this young sergeant was actually not physically fit enough to be in the infantry let alone the scout platoon. Unfortunately, I was not able to get my LT to see that. He actually wanted the guy to take over the platoon’s PT program and turn us all into bodybuilders! Luckily, I had a little juice of my own in that battalion. I went up the NCO chain to the CSM and then we both went to the Battalion Commander. Shortly thereafter, the sergeant moved to the Brigade HQ to be the Brigade Commander’s driver. Together I am sure they could pose for a nice recruiting poster but the truth is that neither one was much of a soldier. My LT never forgave me. He actually thought we had lost an asset rather than removed a combat liability from the platoon. In terms of vehicles, the Brigade Commander and that sergeant were racecars. We all know that racecars look sleek and powerful on dry, purpose built paved tracks. However, they do not do well when conditions are less controlled. Say when the track is wet and those cool machines are all but useless off-road on rough terrain. On the other hand, the Battalion Commander and SFC Myers were high mileage but still reliable pickup trucks. It should be obvious that when there is dirty, heavy work to be done, a pickup truck is much more valuable than a racecar.

Indeed, I have always trusted guys that perform reliably day after day like pickup trucks more than those flashier types who require higher maintenance. Effective PT programs are important. I have believed that, preached that gospel and hopefully set the right example my entire career. However, as you can see here, I do not give too much weight to PT tests. I know this new one is more logistically burdensome than the simpler test it replaces. I expect that it will be a better indicator of overall physical fitness but admit that I do not think the juice – in terms of measurably improved soldier fitness – will be worth the more cumbersome squeeze. I draw your attention one last time to the attached picture. Everything a leader does should focus on preparing your individual soldiers and your unit collectively to fight and win in the harsh reality of sustained combat. Physical fitness is just one of many components that build combat readiness. Keep it in the proper perspective. Finally, always remember that the picture on the left is an imaginary soldier and the picture on the right is a real soldier. I assure you that particular real soldier is in every way the better role model.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

Great article. Very true

In a war filled with heroes that young guy in a helmet, that looks too big, single handedly killed hundreds of German soldiers. Audie Murphy RIP and thank you for your service

Some of the toughest men I’ve met are the most unassuming. They were just plain fit and “ready”.

I recently had a chance to meet Gen. McCrystal. I don’t know why, but I had this image in my head of giant physical stature to match the legend. But here was this man, tough as woodpecker lips, a focused, driven accomplished warrior, who you would probably just walk by on the street if you didn’t know him.

That just once again reinforced to me, it’s about preparation, not just PT.

Thanks for the article.

Terry, once again, an outstanding article. Thank you.

Thanks TLB! Missed you at ASUA, see you at SHOT if you attend.

T

Did not do AUSA this year. Maybe next. Sorry I missed you. Have not thought about SHOT but will consider attending. I will let you know. Saw M.V. (also known as manatee or sea cow) at the reunion last month. He is looking tan, fit and rested. Thanks!

DOL TLB

True words. Great article. Thanks for sharing.

I’m excited about this new PT test because of my many people it’s going to expose. If you watch what you eat and treat fitness as a lifestyle, you will do well on the test. If you don’t, and your version of hard, combat focused PT is a light three mile job and some calisthenics, you will suck on this test. And this PT test will expose you in a way that the APFT never would. The meat eaters will excel. The people who only pretend to be fit will be bared for all the world to see. And there are far too many folks on staff, in leadership positions, or in other jobs who don’t have much oversight from the hours of 0630-0800 who are going to be exposed.

One scale, regardless of your age, MOS, or gender? ? While it’s understandable that the “kick your ass out of the Army” minimum standard will be lower for some of those populations, being able to finally rack and stack a formation based purely on how fit they actually perform on one test will be great for the fitness culture of the Army. There will be nowhere to hide anymore for weak people. You will need to have good cardio AND conditioning AND speed AND strength, or your entire formation will be able to see that you suck.

Forgive the typos – fat fingers and a touch screen will do that :/

You really need to read LTC Baldwin’s article again.

Rudy,

No problem with the typos. I get the gist of what you are saying. I second what JM Gavin said. First, I do not think that the new PT Test will actually do what you think it will. Nor should you expect it to. People sliding on PT or hiding out is fundamentally a leadership problem not a fitness problem.

I believe the new programs can improve fitness and I expect they will. But a PT Test is only an inspection tool to help leaders shape, manage and gage the effectiveness of a unit’s PT program. A PT Test is NOT a punitive disciplinary tool and should NOT be used as one.

In other words, a good leader should encourage soldiers to see PT – including testing – as a positive, NOT as a form of punishment. My other point is that events other than PT Tests like road marches, obstacle courses, combatives or even a well designed multi-day field problem can also help leaders judge real “combat fitness” in ways that no PT Test can.

I mentioned the 70 mile road march our battalion did before TS 83. 25 miles on each of the first two days and 20 miles on the last day. Not at an EIB pace, we marched 12 hours a day so just over 2.0 miles an hour. The point is that it was not just physical exercise but was also a team building event and a gut check.

The intent was not to make people “fall out’ or fail but rather for units to complete the march intact. A good number of platoons had no one drop out including the Scouts. Funny, but that young stud I mentioned was not there. He conveniently had a competition to prep for. The fact is that he was scared. He had the muscles but not the guts. Bottom line: I am trying to say that muscles are good but guts are even better.

TLB

TLB,

Thank you for speaking the truth. Physical fitness is not the be all end all. In 2005 I deployed to Iraq as an AH-64A pilot. In my company was a CW4 who’s first combat tour was Vietnam in 1970 or 71. He was 58 when we deployed, and always described his fitness level as “Round is a shape”. It always drew a laugh.

That being said, his aviation experience was extensive. To those of us that flew with him, we relied upon his mentorship and experience. Some worried about his fitness for the deployment. Whenever I was asked about his fitness, I just said, “I think you have more important things to worry about” In the 10 months we were in Iraq, CW4 Don Campbell flew over 600 hours. More than anyone else in the company.

Fitness is an important part of a Soldier’s life. It helps to mitigate the chance of injury and reduces recovery times after heavy exertion. But combat experienced leadership (formal and informal) is a precious resource. As we reshape our Army after another long and protracted conflict, we work to squander that experience by prioritizing PT Tests and PME over practical experience. The juice isn’t worth the squeeze. I wish the Army would spend as much time reviewing, evaluating and training (at all levels) the lessons learned from the last 17 years of conflict as they have spent on PT tests, Pinks and Greens, and PME.

TLB, please keep up the good work.

Tom

Cool beans

ANOTHER outstanding article.

At the core and in keeping with what is fundamentally important. is it’s always about leadership.

This goes for physical fitness, marksmanship, maintenance, fieldcraft, the “combat readiness” of a unit etc.

The Army has tons of tests to gauge all these things (well maybe not fieldcraft) but they have to be tempered by a discerning eye as to what really translates into combat effectiveness. The Army all too often creates minimums for a large organization to attain guaranteeing an acceptable level of success.

Just as it has been in the past remains true today. Leaders drive the train. They can be happy with the status quo and what looks good on paper or they can challenge themselves and their soldiers to excel.

GREAT article. Thank you for writing it and explaining the fact that performance trumps looks every time.

Great point that sports does not prepare for combat.

With that said, I coached NCAA D1 football back in the early 90’s and here are some sayings from that time:

‘Looks like Tarzan, plays like Jane’

‘All show, no go’

‘Pro bowl body, junior high heart’

In our society, there are a lot of men who need to stop focusing on how they look and start focusing on what they can do.

“In our society, there are a lot of men who need to stop focusing on how they look and start focusing on what they can do.”

Greg, that is without a doubt the best comment that i’ve read on this site today. And its 110% true. We are a society that values looks and appearance over substance and ability. I’ve seen far too many people that are great on the outside, but completely rotten within, and vice versa.

I’ll gladly take the quiet courage of a skinny Audie Murphy over the muscles of Schwarzenegger any day!

Skinny, light, tough and fast is good! “Mr T” type SF hulks in Afghanistan just didn’t feel or look right!

Not from US so potentially missing some of the nuances of the view points expressed so far.

A great debate is happening here at the moment over whether the armed forces in general should move to role related tests without any gender or age discriminators. In fact the process was started by a political goal of opening all trades to women when in fact if it is followed to its conclusion it will make it much harder for women to stay in some roles e.g. artillery which were already open to them.

With far more levels and nuances in the system for role definition for example an infantry private thru to sergeant (which would be everyone at a platoon level, our squad commanders are corporals) would have different requirements to staff sergeant > WO1 (colour sergeant to highest NCO/WO rank) in the same battalion.

Likewise armour and artillery would have different requirements emphasising upper body strength over endurance to some degree.

The whole question of combat fitness boils down to this: Do you have what it takes to win and survive?

Where we’ve gone off the rails is due to the inability of the system to clearly and cogently analyze and define what we really need to be able to do, and then design a means of training and testing for that.

The problem with the classic APFT is this: One man’s pushup is not the same as anyone else’s. A big muscular guy who is classically proportioned is going to be doing more real physics-defined work with every rep than someone else who is built differently, and despite the fact that the APFT scores each rep with same value, the effort produced and work delivered is not at all equivalent. This is a major problem, when you go to start actually performing missions with guys who max out the APFT, and yet who can’t keep up on worksites or humping rucks cross-country. It’s even worse when you add women into the equation, with their gender-normed APFT scales. I’ve yet to encounter an ammo crate or weapons system that adjusted its weight and mass to the person trying to pick it up or use it, so to say that a 98lb female who maxes her APFT has the same intrinsic combat value as that 180lb male that only scores a 250 or so…? That’s flatly untrue, and a complete failure of the thought process going into this whole “combat fitness assessment” we’ve been doing for the last few generations. The classic APFT measures an individuals fitness level, but says nothing useful about whether or not that individual is “fit for purpose” in a combat arms MOS.

I think we really need to drastically rethink much of what we are doing with regards to this, and begin thinking in terms of objective real-world standards: What actual physical tasks does a soldier need to be able to perform? Cool beans if the guys and girls can do stuff like rope climb thirty feet or do a few dozen chin-ups, but the real question is, can that individual actually do the job? Trust me on this–When you’re forming a human chain to load out trucks with ammo boxes, you probably don’t want to place yourself next to that fun-size female troopie who can do a 300 on her APFT, but whose muscle mass doesn’t allow her to actually, y’know, control those heavy-ass boxes as she’s passing them along. I still have the occasional twinge where a young lady dropped a crate of 5.56mm on my right foot several decades ago… She did great on the APFT, but couldn’t hang with doing what the supposedly “less fit” males could do with ease.

As we seem hell-bent on integrating women into the combat arms, this stuff is getting more and more important; we need honest, realistic, and completely objective training and testing. It matters not how many times you can lift your flyweight little ass up to do a chinup; what matters is whether or not you can lift that damn crate of ammo up into the truck, and hack doing it for hours on end as you make up for the MHE that was supposed to show up, and didn’t.