When long gunning it’s common to have an observer with a spotting scope, so it’s important to communicate in a useful language such as Minutes of Angle (MOA) or MIL Dot/increments in scope reticles. In 1988, I was issued my first MIL Dot scope as an 82nd airborne sniper and mounted my fixed 10 power scope to an M-14. Soon after came the spotting scopes with MIL Dots, and life as a sniper/spotter team became much easier. Without reticles or using a red dot, you would still communicate with the shooter by correcting him in feet/inches.

All telescopic sights have windage adjustments that are graduated in Minutes of Angle (MOA) or fractions thereof. A MOA is 1/60 of a degree. This number equals about 1 inch (1.0472 inches) for every 100 yards and 3 centimeters (2.97 centimeters) for every 100 meters. This continues beyond 100 yards, so 2 inches at 200 yards, 3 inches at 300 yards and so on. My 2 inch standard is about the size of the apricot looking fruit at the base of the brain stem called the “Medulla Oblongata”. If you’re a sniper that can shoot a sub 1 MOA, then you can shoot less than a 2 inch group (5 rounds) at 200 yards. A sniper’s commander should know his sniper’s capability before asking him to take the shot. A sub 1 MOA sniper is capable of hitting the apricot out to 200 yards, thus severing the brain stem and lights out! Wind isn’t usually a factor until beyond 200 yards, so I like using a 200 yard zero with my .308 bolt gun.

Shooting beyond 200 yards we need to account for the wind and use the MIL Dot/increments on the cross hairs of the scope and hold into the wind after the observer relays to the shooter how many MILs to hold into the wind. The condition that constantly presents the greatest problem to the shooter is the wind. The wind has considerable effect on the bullet, and the effect increases with the range. This result is due mainly to the slowing of the bullet’s velocity combined with a longer flight time. This slowing allows the wind to have a greater effect on the bullet as distances increase.

It’s important to zero your long gun during all seasons because for every 20 degrees of temperature change, the bullet will rise or drop 1 MOA, so if you last zeroed on a 40 degree winter day and your shooting on a warmer spring day of 80 degrees, your round will climb with the temperature 2 inches at 100 yards just from a 40 degree change. The desert environment can easily have a 40 degree difference within one day. Humidity will also change 1 MOA for every 20 degrees of humidity, but as the humidity raises the bullet will drop due to thicker air density.

Paying attention to the elements and environmental factors is the beginning of becoming a “Train Observer”.

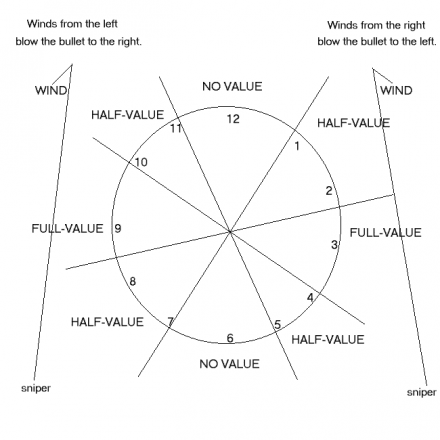

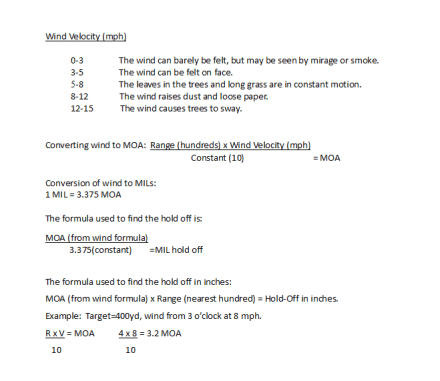

Since the shooter must know how much effect the wind will have on the bullet, he must be able to classify the wind. The best method to use is the clock system. With the shooter at the center of the clock and the target at 12 o’clock, the wind is assigned the following three values: Full, Half, and no value. No value means that a wind from 6 or 12 o’clock will have little or no effect on the flight of the bullet at close ranges.

MOA x R = Hold (inches) 3 x 4 = 12 inches right

The only thing that I can say when buying a scope, “is good glass isn’t cheap”, so you get what you pay for.

Respectfully, Daryl Holland

Daryl Holland is a retired U.S. Army Sergeant Major with over 20 years of active duty experience, 17 of those years in Special Operations. Five years with the 1st Special Forces Group (SFG) and 12 years in the 1st SFOD-Delta serving as an Assaulter, Sniper, Team Leader, and OTC Instructor.

He has conducted several hundred combat missions in Afghanistan, Iraq, Bosnia, Philippines, and the Mexican Border. He has conducted combat missions in Afghanistan’s Hindu Kush Mountains as a Sniper and experienced Mountaineer to the streets of Baghdad as an Assault Team Leader.

He has a strong instructor background started as an OTC instructor and since retiring training law abiding civilians, Law Enforcement, U.S. Military, and foreign U.S. allied Special Operations personnel from around the world.

Gunfighter Moment is a weekly feature brought to you by Alias Training & Security Services. Each week Alias brings us a different Trainer and in turn, they offer some words of wisdom.

Good stuff. Thanks.

The most informative Gunfighter Moment I can remember. Great job.

This was one of the most consicly written and intuitive Gunfighter Moments I’ve read; the reason I look forward to weekend SSD. Every hunter and marksman should read this essay from Mr Holland. Thank you.

I hate to be “that guy” but there is an inaccuracy in the article that is actually not a surprise as it was thought to be the case and taught even when I went through SOTIC.

The part I am referring to is about Humidity. The school house and lots of people for years believed what is posted above to be true (at the time). However, in todays circles, even in civilian precision shooting it is known that the higher the humidity, the LESS DENSE the air becomes, creating less resistance (drag).

Less resistance allows the bullet to travel faster and thus raises it’s point of impact, which in turn requires the shooter to lower his elevation.Humidity has little effect at shorter ranges ( under 600m for 308;300 for 5.56). A 20% change in humidity(from the humidity when you zeroed or later in the day even) for 1 MOA is a correct rule of thumb and the rule of thumb is Humidity up=sights down; humidity down-sights up