The issue of poor foreign language capability among SOF operators, particularly US Army Special Forces, rolls around about once a decade, usually flip flopping with the lack of racial diversity within SOF.

Last month, the Government Accountability Office released a report entitled, “Special Operations Forces: Enhanced Training, Analysis, and Monitoring Could Improve Foreign Language Proficiency.”

No kidding, even the title belies what any amateur detective could tell you. What’s amazing is that if it’s so obvious, why isn’t it being done? I mean they sound like simple, measured responses to any training deficiency. As is generally the case, the situation is more complicated than you’d expect.

The GAO found that for the last several years, SOCOM did not meet its language proficiency goals. This has long been a challenge within Army SF which has relied on its language capability to interact with foreign forces, both government as well as civilian.

About 20 years ago, the Marine Corps got into the SOF game with the formation of Det 1. Basing itself off of traditional Marine capabilities, it had a serious special reconnaissance and direct action bent and it was really good at it. But SOF is political and Det 1 was an experiment. There was no interest in yet another SR/DA unit in the mix. The only way the Marines could get a permanent component within USSOCOM was to agree to pick up some of the Foreign Internal Defense missions traditionally accomplished by Army SF who were themselves concentrating on SR and DA missions during the GWOT. The Marines set up what was known as the Foreign Military Training Unit.

For the Marines, this new mission meant cultural and language proficiency. Initially, the Marine Corps embraced the mission, but today, MARSOC looks much different and has settled back to mission sets it is more comfortable with. Regardless, they’ve retained language capability for their Critical Skills Operators and MARSOC is where SOCOM finds its lowest language capabilities, joining Special Forces’ long struggle with the issue.

Both the Army and Marine components of SOCOM know there’s an issue and are trying some things out. For instance, a few months ago, Army students with 2nd Special Warfare Training Group participated in a language trading course hosted by Marine Raiders. The experience included instructors from the SWCS course. It’s a step in the right direction.

I’d hazard a guess, having served as a linguist in the command, that SOCOM has never met its language proficiency goals. Much of the problem is that on top of the many mission essential tasks an operator must maintain proficiency in, the command as well as the operator’s parent service dumps loads of HR-focused annual training requirements. There aren’t enough days in a year to do it all. The GAO report acknowledges that there are competing training requirements.

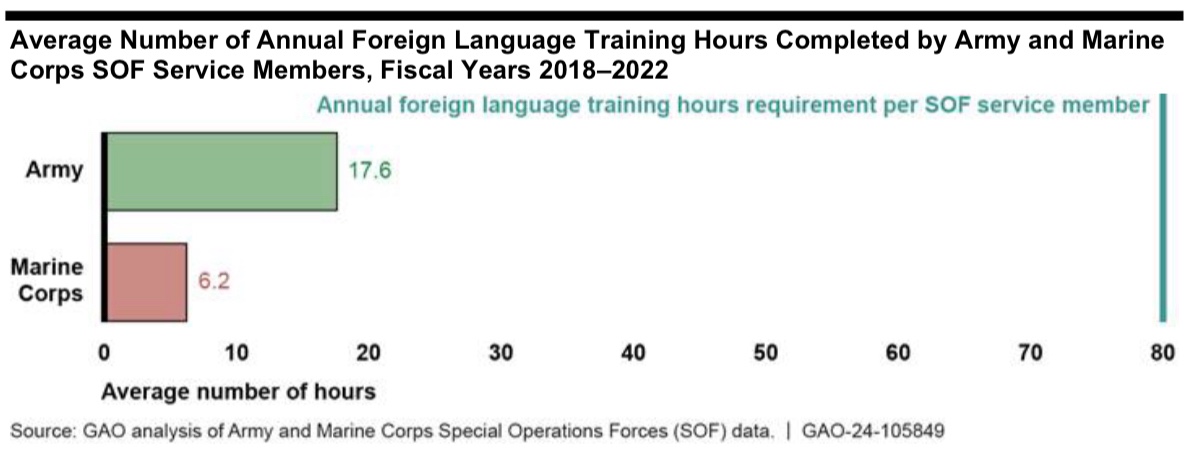

However, based on this chart, you’ve got to wonder why Army SOF personnel are getting three times the amount of training of SOF Marines. Sure, they’re both facing lots of required training, but culturally, the Army side seems to pay more attention to the capability. Regardless, they are both falling woefully short of the minimum 80 hours of foreign language training per year.

One of the GAO’s findings is that commanders aren’t being held accountable for unit members not attending language proficiency training. Less than half of SOF personnel attend the training, so the question is, “Why?” Tracking the issue might help, but commanders are already being tracked for many other training requirements there isn’t enough time in the calendar to fulfill.

To me it seems like a cultural issue. If they want effective language capabilities then they are going to have to demand it at the unit level and that falls on commanders, at all levels.

The average SFOD-A or 12 man A-Team commander is a Captain who gets about 24 months of command time. For the vast majority of Special Forces officers that is his only action guy time. Consequently, he is going to hope for an operational deployment and fill as much of the rest of his command time with training on the more exciting aspects of his mission letter, like weapons training, infil skills, and so on. For most, the last thing he is going to want to do is spend a couple of months with his team in language immersion training. Now, put the Warrant Officer in charge for a while and he’s going to insist on it, particularly if it’s down range somewhere and away from the flagpole. While the Captain is focusing on the Officer Efficiency Reports which are going to make or break his career, the Team Technician and the Team Sergeant are looking at the long view and the investment in personal and well as team capabilities. I can only imagine that MARSOC faces similar challenges.

Historically, when SF teams have needed language capabilities they relied on one or two of their guys who are either native speakers or are just good at picking up languages to carry the weight. During the GWOT, teams were assigned interpreters or ‘Terps because so many teams were regionally focused on other areas and their trained languages were all but useless in the Middle East. This latter circumstance helped further erode focus on inherent language capabilities both within SOF as well as associated enabling intelligence specialities.

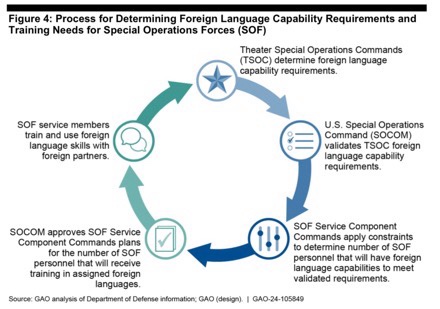

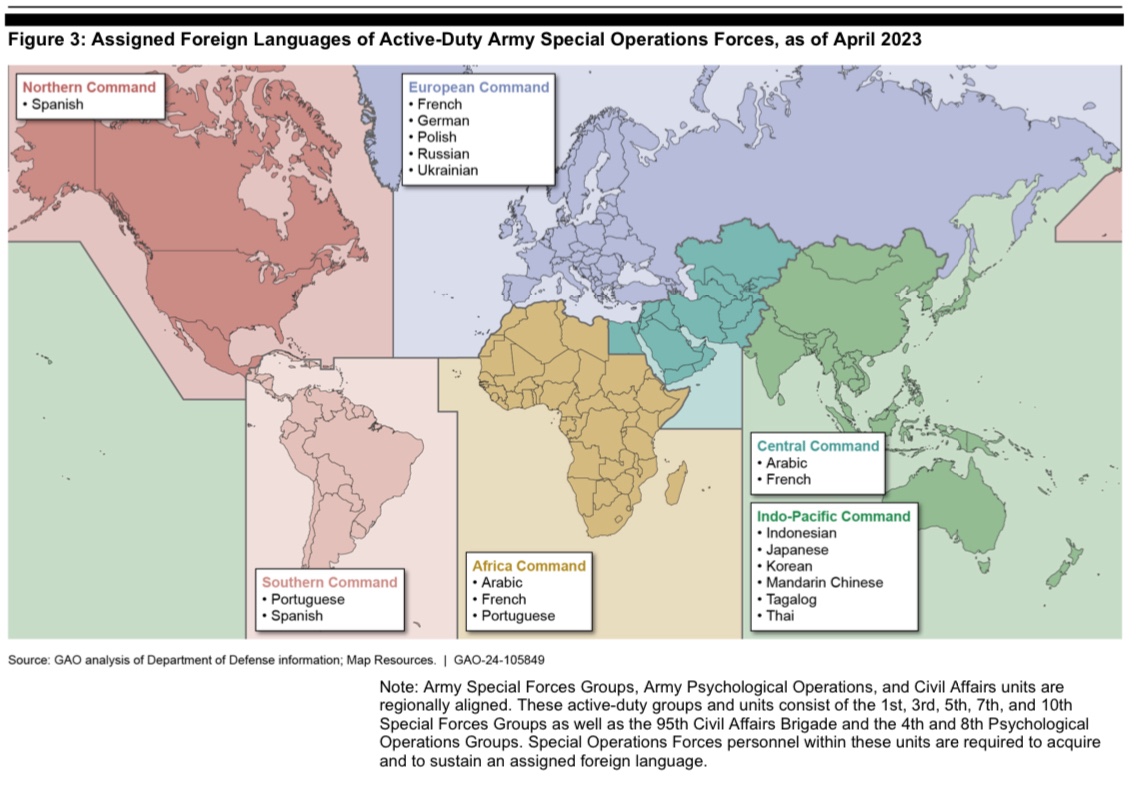

This leads to another major challenge, the breadth of language requirements within the command.

Based on 2020 requirements for required languages and associated proficiency levels (level 1 for basic survival to level 3 for professional proficiency), the Theater Special Operations Commands within the Geographical Combatant Commands identified 80 foreign languages.

Generally, the armed services want to limit their language programs to those which it has a likelihood to encounter operationally. It’s just easier to manage.

Note this report lists the command’s language requirements. While the intelligence community holds its actual linguist requirements close to the chest, it’s well known that the low density requirements exist because of SOF requirements. For example, I was a French and Haitian-Creole linguist. Those duty positions were unique within SOF, whereas Russian, Chinese, Spanish, and Arabic linguists are found across DoD.

As you can imagine, the management aspects of this enterprise, consisting of 80 languages with linguists in five components is rather daunting. What’s more, it’s rare that you’ll have the right linguists at the right place, at the right time due to the enormity of the mission set and the limited number of SOF personnel. Such a situation led to the use of local interpreters discussed earlier.

It’s no wonder USSOCOM is investing in Artificial Intelligence / Machine Learning capabilities to assist with language translation challenges. However, these technologies may be able to also assist with training, particularly in low denisty languages which are more difficult to arrange training for.

It should be mentioned that both Naval Special Warfare Command and Air Force Special Operations Command suspended their command language programs making the Army and Marine components the focus of this report. Neither of those commands did any better in maintaining proficient linguists when they had programs.

However, all of the SOF components continue to have assigned linguists whether or not they have a command language program. They are generally a mixture of operations and intelligence personnel. Intelligence language programs may be managed separately due to occupational specialty requirements.

On a final note, this report focuses solely on the capability of 18-series, PSYOPS, and Civil Affairs personnel on the Army side and Critical Skills Operators for MARSOC. It does not include the assigned linguists within the intelligence community assigned to these units even though some of my examples stem from my experience as a Crypto-Linguist with 3rd Special Forces Group in the 90s and observations as an intelligence officer assigned to Air Force and Joint SOF units later in my career.

There’s no easy answer here, but it starts at the unit level. If they focus on languages and regional cultural skills, they will develop them. Another training status slide at MacDill isn’t going to improve the outcome.

You can read the full report here.

You’re right Eric, it’s a complicated issue. I was on a team that had six different trained languages present but the only one we operationally used was Arabic. It’s difficult to maintain and test something that you only use in the classroom once a year. Most guys learned slang Arabic to get around but couldn’t test in it to any degree.

TR

You hit on my issues especially the OER/FITREP polishing. All services suffer from checking boxes for the OER. The current system of promotion is too rigid, too focused on getting boxes checked versus actual performance. The requirement for “diversity” does not let any office focus on his job. Rather than have well trained specialists we have “diversity”. You kill your career by not taking “diverse” jobs. The promotion systems also focuses on every officer being the CNO/Chief of Staff. DOPMA ‘86 and “Joint requirements” destroyed the officer corps. Let the eager check the boxes for Flag positions and let the majority of officers focus on mission accomplishment and being good in their craft.

DOPMA is an industrial-age personnel system. However, it is the Services, the Services’ respective cultures, and the communities and functional area that determine what is considered valuable to enable an officer to progress through the system. General/Flag officers are required to be Joint Qualified Officers by the time they are promoted to O-7. That requirement needs to be completed by the second half of an officer’s third decade in uniform. The Services push those timelines left to identify the “go getters.” Not all communities value a diverse background. For example, its not uncommon to have Air Force and Navy fighter pilots remain in flying billets for 15 years before “checking the box” with a 24-month Joint tour, and returning to squadron command.

If the Service and community value things like language proficiency, then the community leadership will promote officers that emphasize that capability in their units.

Thank you for the thoughtful analysis Eric.

Better pay incentives for maintaining the tedious and time-consuming pursuit of a legit language capability is one solution. Focusing on fewer languages based on threat is another. Slowing down promotions and decoupling rank and pay to some degree is yet another, particularly junior SOF officers. Who wouldn’t, in hindsight, have benefitted from spending more time in the junior officer ranks? IOW, slow down the promotion/check the block race for the junior O’s but keep the pay raises coming on a regular basis. We could learn a lot from the aviation community and some of our allied partners. Once you’re field grade, the promotion pace can accelerate based on ability and career promise because 99% of us are basically glorified paper pushing staff/leaders to LtCol and then either doing your final 05/06 command with head held high or going all in checking all the yes man/kneepad blocks needed for GO.