A few days ago on this site some commenters noted that many professionals, especially leaders, do not have the inclination or opportunity to truly do any deep reflection on their craft until after retirement. For myself personally that has certainly been the case. Part of that process for me has been renewing the effort to learn more and reread and relearn some of the more challenging and ambiguous concepts I was taught earlier in my career. More on that at the end; but first please consider the synopsis below of a discussion I had recently in another forum.

Machiavelli is a fascinating and complex historical character. He was an early champion of a pragmatic and morally relativistic philosophy of realpolitik that ethicists would eventually label as consequentialism or utilitarianism; sometimes reduced to a simple statement that “the ends justify the means.” Machiavelli lived in a time of an almost constant series of conflicts between city states and Papal political machinations and territorial ambitions. Constantly shifting alliances, ‘court intrigue’ and reversal of military fortunes was the norm as ‘Princes’ maneuvered overtly and covertly for relative dominance. A real life chess match or “Game of Thrones” minus the dragons.

That was the political / military ‘game’ that Machiavelli enthusiastically participated in – albeit as a mid-level player with perhaps outsized influence – during his adult life. By the time he was in his late 40s he had developed a signature philosophy and made the effort to write it down and share it initially with his contemporaries and then with posterity. I have extracted just two quotations from Machiavelli’s The Prince that are illustrative of what he believed in and preached. “Hence it is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity.” And also, “Therefore it is unnecessary for a prince to have all the good qualities I have enumerated, but it is very necessary to appear to have them.” Ideas like that – in many cases taken out of full context – contributed to popular perceptions of Machiavelli’s views being both indefensible and amoral if not immoral. For the record I have always found Machiavelli’s thoughts to be rational and valuable if considered in their entirety.

Clausewitz tells us, “War is merely the continuation of policy by other means” and therefore “there can be no question of a purely military evaluation of a great strategic issue, nor of a purely military scheme to solve it.” Sun Tzu also highlighted “the close relationship between politics and military policy, and the high social cost of war.” But both of those men were proficient and experienced soldiers and viewed, referenced and wrote only briefly about politics from that limited perspective. Machiavelli, on the other hand, was an amateur soldier but was undeniably a professional and talented politician. He was able to describe – in terms that soldiers can relate to – what war looks like as seen through an unapologetically political lens. He innately understood what we now call power relationships and interpersonal dynamics.

Machiavelli’s ideas were controversial even in his own time. The Roman Catholic Church banned his writings. Later his philosophy became indelibly associated with acts of political extremism because it was explicitly used to rationalize genocidal policies like the NAZI “Final Solution.” Today terrorist organizations almost by definition use Machiavellian thinking to try to justify their heinous crimes (means) against innocents in furtherance of a twisted but in their minds sacrosanct goal (end). They obviously believe that their sick ends justify even the most despicable means – even if they never actually heard of Machiavelli.

But those disturbing facts should not be allowed to detract from the larger veracity and utility of Machiavelli’s astute perceptions. This may be surprising, but his philosophies are not just applicable to ruthless ‘bad guys’. “The ends justify the means” is in fact a fundamental and universal principle that is and always has been considered in all political and military decision making in democracies and dictatorships alike. Every leader applies that brutally honest standard to every consequential decision whether they acknowledge it or not. Oftentimes we say it in this more palatable way “it is for the greater good” but the underlying logic is the same.

I’ll share two examples. In the 1930s an organization called the “Tennessee Valley Authority” (TVA) was part of an initiative to bring electricity to impoverished rural areas. To do so required the displacement of thousands of people so that rivers could be dammed and valleys flooded. Many of those people did not want to go but were forced out – a good number literally at gun point. I would certainly be willing to argue that it was “for the greater good” but those people forcibly removed would not. And it represents just one of countless domestic political decisions that are clearly based on the positive ‘ends’ justifying the not-so-positive ‘means’.

Let us consider the recent deaths of civilians in a U.S. airstrike in Mosul. The accidental killing of civilians in war is not usually considered a ‘war crime’ unless there are other factors like ‘gross negligence’ involved. But a good number of people – even Americans – would likely consider any airstrike that apparently killed more than 100 innocents “an extremely wicked or cruel act” a.k.a. an ‘atrocity’. But those air missions in support of fierce house to house fighting by Iraqi forces remain our best ‘means’ of achieving the worthy ‘end’ of ISIL’s occupation of Mosul. So today and tomorrow and the next day pilots will climb back into cockpits and they will drop more bombs. The alternative is to do nothing – and that is not an acceptable option; not for us, not for the Iraqi government and ultimately not for the people of Mosul.

What is disquieting for most people is that the ‘good guys’ and the ‘bad guys’ use the same Machiavellian reasoning to justify their respective actions. But there is no avoiding reality. There are few if any truly important decisions that are black and white. A political or military leader would not be able to function if he or she cannot make hard and morally ambiguous gray decisions. The Legislative process would be impossible and even the most just war could not be prosecuted if the ends NEVER justified the means.

That is not to say that we have to therefore accept any and all ‘means’ in order to achieve our ends. No rational person would have supported massacring those people in Tennessee in order to dam a river. No leader in uniform thinks that “killing them all and let God sort them out” is an acceptable ‘means’ of liberating Mosul. It is illogical and bizarre to argue that one can somehow “save” a village (desired endstate) by destroying it (unsuitable means). There are serious and often harsh judgements to be made and scales of just and unjust, acceptable and unacceptable that leaders constantly try to balance.

In professional military education programs today Machiavelli is usually examined and earnestly debated only in terms of ethical or unethical behavior. He practiced what we now call “situational ethics” as a virtue. But is it? Soldiers are in a business that routinely involves killing and destruction. In fact, as long as we follow the Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC), the controlled application of violence and the threat of violence by military forces are socially and legally sanctioned. We are empowered to use lethal force largely at our own discretion. But with power comes equal responsibility – and equal moral ambiguity. There are countless examples. Sherman’s march to the sea for instance. He essentially argued that by causing immediate suffering and burning Atlanta and other towns the war would end sooner and that was actually the most humane and militarily sensible thing he could do. I would agree. A similar argument was made in 1945 with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Again I for one would agree that Truman made the hard but ‘right’ decision.

That is what Machiavelli was able to describe so well – a realistic and pragmatic world view in which leaders have to make very difficult decisions that are invariably shades of gray and almost never black and white. When I order an air strike to support my ‘troops in contact’ I have to accept the fact that I cannot be sure that innocents will not also be killed by those bombs. Soldiers must make those kinds of tough decisions in war every day. Sometimes “situational ethics” is what one has to work with. And yes, that routinely looks a lot like the “ends justifying the means”. War is not morally or ethically neat and tidy – and neither is life – and that is why conscientious professionals still read and study Machiavelli for pertinent insight.

So why Machiavelli and why now you might ask? The answer is simple; to enhance my own education I signed up for an online Master’s Program in Military History this last December. It looks like a great learning vehicle and allows me to make good use of my remaining G.I. Bill benefits. And that is something I would recommend for anyone with educational benefits available that you have not yet used. Don’t let them go to waste. Of course the class workload has also cut into my ‘free time’ for other writing projects. I won’t lie to anyone; it hasn’t been very much fun to put my nose back against an academic grindstone. In my case it has been a very long time since I was last a student. But I firmly expect the end will justify the means.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (RET) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments.

Tags: Terry Baldwin

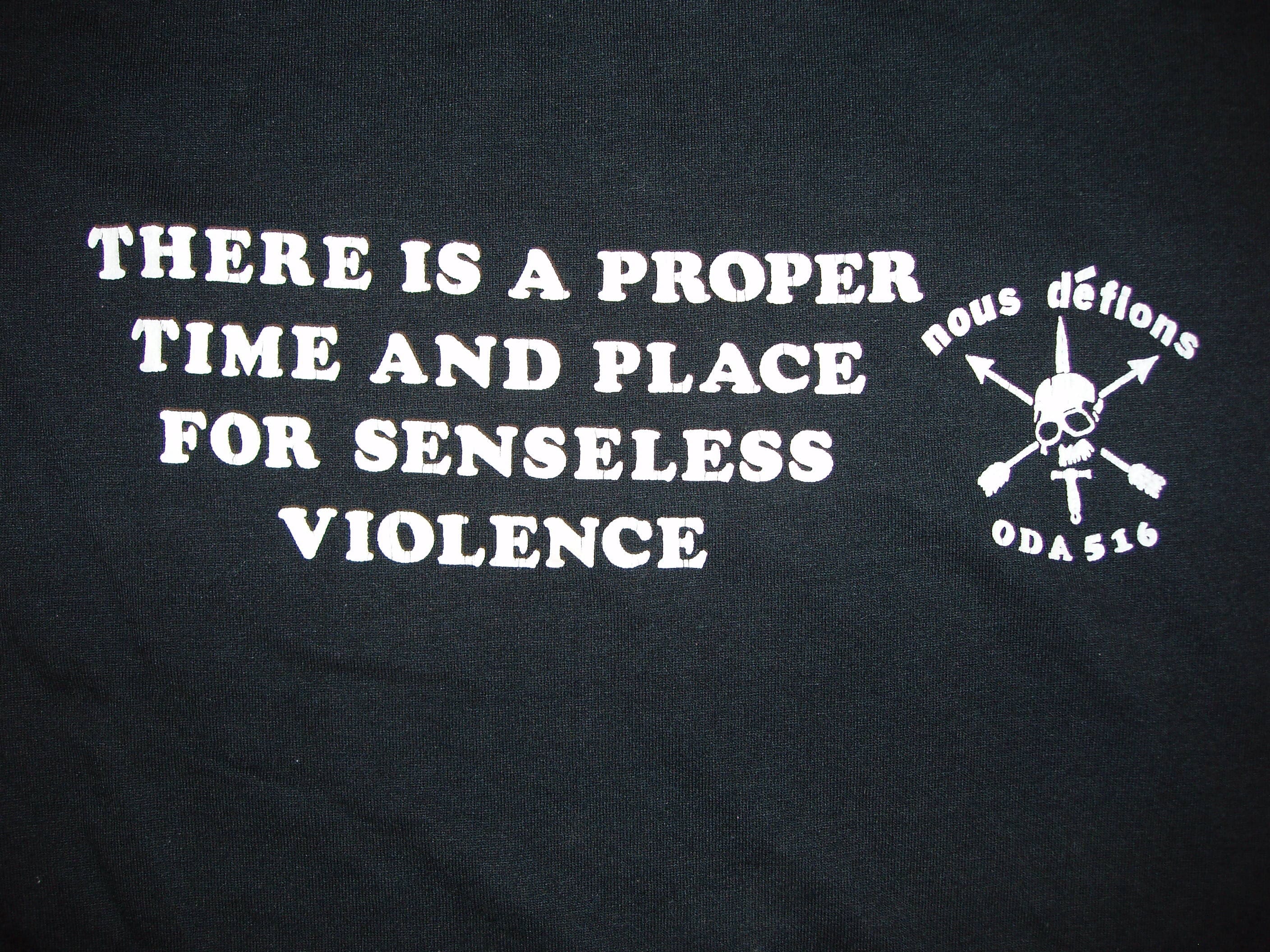

ODA 516, interesting, That was our team…

G1E,

Mine too, and that was our motto, 91-93.

TLB

Arguably the best scholarly article ever published on Soldiersystems.net.

Um, everything this article states about Machiavelli and The Prince, is incorrect. The Prince was written for Lorenzo Medici, the recently installed prince of Florence, which ceased to be a Republic, once Giovanni Medici, became Pope Leo. So, no it wasn’t satire. Please study history.

Cameron,

I never said it was satire. Nor did I ever imply that it was the only influential work written by Machiavelli. The article is not focused on The Prince – although the conversation has gone in that direction. I provided just two quotes from The Prince in paragraph three above.

Do those quotes seem satirical? I don’t think so. The second says essentially that your (real) personal character and your public persona need not be the same. I think that represents sound, albeit cynical, advice for any public figure.

TLB

Thank you Terry! Very thought provoking and well written.

– Steve

Great article! I wish the general public would read articles like this.

Very good summation of “the ends justify the means”. Most people think that Machiavelli concocted an evilness with that phrase, but most that understand it, are the ones that actually read The Prince.

An inspiring and impressive article. All I would presume to add is Mushashi’s A Book of Five Rings, is another book that is mandatory reading

I thought I’d plumbed the depths of commissioned historical ignorance, but just when I think I have… A new contender appears. I had to read this twice to make sure I was

Before you make the fairly common mistake of reading The Prince as a serious work of political philosophy, you first have to ignore everything else Niccolo Machiavelli ever wrote, and all the surrounding historical context.

The Prince is pretty clearly satire, not a work of actual political advice for how a “Prince” should conduct himself and the affairs of his nation. It is in the same vein as Swift’s A Modest Proposal, where he advocates the raising of Irish babies for meat, as a means of dealing with the Potato Famine. It is, in other words, purest Juvenalian satire, not the serious work of real-world political philosophy every halfwit takes it for. He is making mock of a then-current political figure, Cesare Borgia. This isn’t exactly some bit of esoteric lore, either–Google up “The Prince as satire”, and you will find reams of scholarly work making this case. If you actually bother to go dig up the rest of Machiavelli’s oeuvre, you will find that everything else he ever wrote was quite at odds with how and what he wrote in The Prince . Niccolo Machiavelli suffers from the fact that the only major work of his to make it into translation into English and widespread notoriety was The Prince , and instead of it being treated as the satire it was, the translations treat it as a serious work–Which was quite in keeping with the prejudices of the time, in the English-speaking world.

Niccolo Machiavelli was a Florentine patriot, a man whose position and nation was trod under by the Borgias, who he loathed. The Prince makes no sense as a work of practical political advice to the men he hated, and is unlike anything else he wrote. As Juvenalian satire, however? It becomes quite clear that we have been misreading this work nearly since it was translated. Doubt me? Do your own research, and don’t stop with the conventional wisdom–Go read the rest of Machiavelli’s works, learn the actual historical context, and see if you don’t find yourself seeing the same things I did. The Prince is not what it is being sold as, here or anywhere else.

Note: The above was posted from a tablet. This isn’t.

Seriously, you have to really work at things to read The Prince, and not cotton onto the fact that it’s a totally unique work, different from everything else Machiavelli ever wrote. I ran into this the first time I read The Prince, because it was sold to me as a part of a collection of other pieces of Machiavelli’s writing. If you read the rest of his work, the contrast is really quite glaring–And it makes taking The Prince as a serious work nearly impossible, once you key into the background information that most English-speaking folks don’t bother to dig into.

Niccolo Machiavelli was a Florentine (although technically not a full citizen) during the era it was a powerful independent republic. He served as a diplomat and official in the military administration of the Republic, until the Medici’s hit town. His family was intertwined with the leadership of the Republic going back generations–He was not, in plain, the big believer in tyranny he’d have had to have been to write The Prince as a serious work.

There’s a hell of a lot of context surrounding The Prince that has to be ignored or left out, before you can even begin to take it as a straightforward work of political philosophy and advice. Lots of people treat it far more seriously than it warrants, and I suspect that when Machiavelli wrote it, he was venting his spleen–Which is why it is so damn readable, and the turn of phrasing used throughout is so cattily vicious. The man was pissed-off, and unable to really speak clearly, being as he’d been under torture and was still living in areas under the control of his enemies.

So, the satire is subtle, I’ll grant. But, when you take it in comparison with his other, more straightforward works? It is almost impossible to read it as anything but satire, and were the people who it was targeted at to have taken it as serious advice…? Yeah; ask Cesare how that all worked out for him.

Kirk,

I agree that The Prince is different from Machiavelli’s other works. I disagree that it is satirical in nature. And yes, I am aware that some have made that claim.

Below is just one random passage from The Prince. No mockery or satire that I can detect – subtle or otherwise. I’ve also read his L’Arte della Guerra (The Art of War) which is largely lifted from Vegetitus. The man did have range.

“Thus King Louis lost Lombardy by not having

followed any of the conditions observed by those

who have taken possession of countries and

wished to retain them. Nor is there any miracle in

this, but much that is reasonable and quite natural.

And on these matters I spoke at Nantes with

Rouen, when Valentino, as Cesare Borgia, the

son of Pope Alexander, was usually called,

occupied the Romagna, and on Cardinal Rouen

observing to me that the Italians did not understand

war, I replied to him that the French did not

understand statecraft, meaning that otherwise they

would not have allowed the Church to reach such

greatness. And in fact it has been seen that the

greatness of the Church and of Spain in Italy has

been caused by France, and her ruin may be

attributed to them. From this a general rule is

drawn which never or rarely fails: that he who is

the cause of another becoming powerful is ruined;

because that predominancy has been brought about

either by astuteness or else by force, and both are

distrusted by him who has been raised to power.”

The rest of the text is written in exactly that same fairly straight forward style. “Iustum enim est bellum quibis necessarium” war is just which is necessary. Again I don’t see any good case that he was being satirical in his use of language.

Machiavelli was a player. He dedicated The Prince to Lorenzo de’ Medici. Did he have an ulterior motive? No doubt. Probably to ingratiate himself with a potential up and comer. Was he trying to topple those in power – or just poke them in the eye – though his writings? If so he was too clever by half because it had no such effect when it was contemporaneously published.

Based on Machiavelli’s writings, he is widely considered the father of modern political science. So I am not the only one who takes his philosophical musings on politics seriously. If you choose to see them as more tongue in cheek, so be it. We’ll agree to disagree.

Excellent discussion.

TLB

It’s satire. It can’t be anything but, considering the rest of his work, and his life.

Read the rest of his writings, and his full background. Machiavelli was basically the Donald Rumsfeld/Dick Cheney of the Florentine Republic, only with a classicist bent and able to write superlatively. He’s noted still for his turn of phrase in Italian and Latin, and considered one of their better historians.

I read The Prince in high school, as part of a recommended reading list from a history teacher that was having to deal with a very bored student. Didn’t get much out of it, decided to re-read it in my twenties, which was when I found other stuff of Machiavelli’s in the same collection. Reading that second time led to some considerable cognitive dissonance, because much of what he wrote sounded like it could have come from the Founding Fathers–And, indeed, he was very influential with them, just not via The Prince. You’ll find a lot of his thinking reflected in a great deal of things the Founders wrote and discussed, just with the serial numbers filed off because The Prince and its misinterpretation had already polluted his reputation. Read Machiavelli on militias in relation to a republic, and then do a quick compare/contrast with the Founders on the same issue–You’re going to find a lot more continuity of thought than you would think possible, and if you take The Prince at its outward value, you’re going to be left wondering which was the real Machiavelli. I’m going with what’s congruent with the vast preponderance of his work, which leaves The Prince as either the antithesis of the man, or… Satire. Being as he only ever intended it for close-hold circulation amongst trusted friends while he was alive, I’m going to fall in on that explanation for why it’s so different from the rest of his work.

I read him again, in my thirties, when I was researching what went into the Revolution in Military Affairs back when Maurice of Nassau was re-introducing drill and other features of classical disciplined warfare in the modern era. And, backing into it, who did I discover was extremely influential with Maurice and those around him? Niccolo Machiavelli, again not through The Prince. His Art of War and Discourses on Livy were highly influential on that crowd, and probably contributed a great deal to the formation of the Dutch Republic, and through that, to our own. Swiss militia doctrine? Dutch drill? Machiavelli and his “other works” are there, somewhere in the background.

There’s more to Machiavelli than just The Prince, and I really find it highly annoying that people read that work unironically, and with a straight reading of his meaning. He wasn’t writing to say that the conduct he was describing in it was to be emulated, or that it was good, any more than Swift was advocating for the sale of Irish babies as adjuncts to fine dining. Machiavelli is remembered as some kind of monster, when in fact he was a staunch republican in the old sense of the word, a man who was tortured by the Medici and the Borgias because he fought for the Florentine Republic. The Prince wasn’t even published until five years after his death, and he’d only ever circulated it to friends, more than likely as a “take that” to Cesare Borgia who by that time was a fully-failed wannabe tyrant. He should be read for so much more, and remembered for more than that cynical work, The Prince.

I don’t think Niccolo would like how he’s remembered, today, and would be shocked to find his reputation is what it has become, and what it was based upon. The Prince is not at all what you’re interpreting from it–And, that’s not just some off-the-wall opinion I’ve pulled out of my ass, either. There are a lot of people who are far more familiar with the material and the era that have the same opinion.

Given how much influence the rest of Machiavelli’s work has had on modern military thought, and the basis of our republic, I’m actually rather appalled that people are still writing things like this piece. It’s like writing an article about the English language and its evolution, while leaving out the influence of Latin and emphasizing the things English takes from the other derivative Romance languages.

I think at the least, an acknowledgement of the alternative interpretation as a Juvenalian satire should be included, because the sad fact is that most people dismiss Machiavelli as an apologist for tyranny and bad governance, while quite the opposite was actually the case. If only for the influence he had on men like Maurice of Nassau, and the Founders, he should be read and remembered for his other works besides The Prince.

I’m neither agreeing, nor disagreeing with most of the above. I would like to agree with one thing only that Kirk has said, and that is that sometimes words, meaning, and context do get lost in translation. I have seen it, in a completely different case, trying to translate another language into English.

I’m going to have to find some time to catalog as many versions of the English versions for any differences before I find an Italian version(s) to compare it to.

I think you’re going to find that most of the comparison information you really need isn’t necessarily in the actual translations and original words, but in the surrounding matrix of history and events.

I’m having to pull a lot of this out of really deep memory–The last time I really dove into this particular milieu and question was awhile ago, and when I last was paying attention to the issue, the interpretation of The Prince as satire was (I thought…) well settled.

Hell, Garrett Mattingly was making the case for this back in the 1950s, fertheluvamike…

http://www2.idehist.uu.se/distans/ilmh/Ren/flor-mach-mattingly.htm

I think he makes a very convincing case, and I have yet to find anything to disagree with in what he says. Granted, I’m not a Renaissance Italy expert, I don’t speak Italian or Latin, but having been through more of Machiavelli than just The Prince, I’m pretty well convinced that this work was intended as a cunning satire he wrote for private circulation among his friends. One thing that is telling is that there has yet to be found a fancied-up presentation-grade copy of this thing that he would have submitted to the Medici or the Borgias for their personal perusal–And, if the theory he changed his mind and wrote this as an attempt at regaining favor with them were true, you’d think that there would have been such a thing. As well, The Prince did not see wide circulation or publication in Machiavelli’s lifetime, and if he’d really been writing this thing in full seriousness, that’s something else that should have happened.

I think the entire situation surrounding The Prince argues for it being a dark satire he wrote to vent, and the problem has been that everyone has taken it at face value. You compare it to the stuff he was “writing to convince” with, and there’s this massive difference in tone and language that just leaps up at you, even through translation. As well, the fact that he’s only ever taken on this “advice to tyrants” posture in the one work, while laying out the pitfalls and benefits to a republican form of government in everything else he ever wrote…? Yeah; satire.

Kirk,

I really do appreciate your keen insight on this subject. Minus the “I’m right and anyone that doesn’t agree with me is obviously stupid” component. I know that is a classic gambit and never goes out of style but it doesn’t strengthen your core argument.

Conflicting interpretations of all of Machiavelli’s works, perhaps most especially The Prince, are out there. But there is no consensus that he was being satirical when writing The Prince. Nor is it accurate to imply that view somehow represents the majority opinion of professional historians. It does not.

I am more familiar with the context of Machiavelli’s writings then you are giving me credit for. I didn’t just read The Prince in isolation and jump to a allegedly false conclusion as you charge.

I know that Thomas Jefferson had a copy of Machiavelli’s The Art of War on his personal bookshelf. As likely did other Founding Fathers. Clausewitz specifically identified Machiavelli as one of his influences in political thinking.

And as Mike Nomad notes below, Machiavelli himself directs the reader to his own Discourses on Titus Livius in The Prince. Which begs the question, why would he provide a cross reference if The Prince was “dark satire” not to be taken seriously?

I truly enjoy this kind of dialog. My purpose is not to convince you or anyone else to agree with me. I have provided my perspective. You have provided yours. Hopefully this will encourage others to read Machiavelli for themselves and come to their own individual conclusions.

Someone once told me that the purpose of education is not to achieve some singular unity of opinion but rather to improve the intellectual quality of our heated debates. Sua Sponte!

TLB

I have to admit that my original post was intemperate and more confrontational than I would now mean it to be.

The thing with Machiavelli that drives me nuts is that everyone looks at The Prince as being nearly all of him; that’s how he is remembered. But, as you acknowledge above, there’s a hell of a lot more depth to him, and works that are completely at odds with The Prince.

That you cite Jefferson as one of his readers? That is not accidental, at all. His influence, through his other works, permeates a huge background swathe of both European military history, and our own political background. I’m not kidding when I say that a lot of what the Founders wrote and thought about the militia is basically Machiavelli with the serial numbers filed off.

As well, there’s the early influence on the things that went into the Dutch re-development of drill and the recreation of Roman discipline and military policy. His fingerprints are all over the professionalization of the European military order as they transitioned from feudalism to what we would recognize as modern practice–Which, again, comes down to us through men like Myles Standish, who learned his trade as a soldier under men who were greatly influenced by Machiavelli’s ruminations on republics and military philosophy. His influence can be discerned in much of the early colonial militia set-up and administration, probably through the influence of men like Standish.

This is why I find it irritating in the extreme when he is presented only as this eminence grise behind tyranny. A full appreciation of his work and lasting influence (which, thanks to The Prince is hardly ever honored) requires that even if one takes The Prince at face value, you have to mention the “minor” fact that the vast preponderance of his work and contributions are at complete odds with The Prince.

There’s a much broader picture here to be presented, and I fear that you’ve only barely touched on the one dark corner of it all. Which is what set off my intemperate initial response…

I’ve also got to commend you for your patience with me, and your gracious responses. I need to learn not to post in the heat of the moment, and consider my responses with more temperance–Although, I do have to point out that by only presenting the one commonly held aspect of Machiavelli’s work, and not at least mentioning the other 99% of his oeuvre, you’re almost certain to find someone like me who’s going to be set off by your not mentioning the other aspects of his work.

I’m dead serious about that, too–Machiavelli deserves a far better reputation than he has attained in the English-speaking world, if only because of how his other works influenced a whole raft of things, right up to our own military history until the National Guard acts.

Seriously–Go digging through what he wrote, and do a quick comparison to the portions of our Constitution relating to national defense, and I think you’ll find yourself going “Damn…”. I know I sure as hell did–Much of the Founder’s thinking about national defense policy is almost a point-by-point rehash of Machiavelli’s work discussing the same issue.

For that fact alone, he deserves a more thorough and complete consideration than he usually gets. To a degree, I think The Prince is a vastly overrated work, in terms of its relative importance as a part of Machiavelli’s contributions and work. It’s one short pamphlet-length work that he probably threw off in fit of anger after the fall of his country and ensuing torture, and compared to the volume and content of the rest of his writing, it really should be considered almost incidental apocrypha to his overall work–Even if he meant every word of it without the slightest hint of irony.

Great discussion, thank you!

While I haven’t taken it as satire , neither have seen it as an instruction manual. I tend to look at The Prince as a bit of a warning or guide to enemy tactics. ” This is how they think,and how they will react” sort of thing.

Outstanding Sir. Thank you very much. This article is just another example of why I try to read SSD on a daily basis.

Great article Terry! My take on this my be slightly different from the above commenter; I’m reading this as an explanation of the decision making process at the tactical level (and some times strategic from my personal experience). What is taken as a wartime (and in everyday life) euphemism “the ends justifies the means” most people who say or think those words have no idea where they came from. I think this article puts those words into a historical context. Terry, next time I see you I’ll buy you a beer and explain some of the thinking (like what you have written above) that went into running a province in IZ and how it had strategic value added to the east. T

T,

You are exactly right. This was meant more as a piece on real-world decision making using Machiavelli as the vehicle.

The discussion went sideways from my original intent. But it has been an interesting conversation.

I look forward to sitting down with you and talking about it some time in the near future.

TLB

I wasn’t aware there was a The Prince as Satire contingent. Talk about laughable lack of context…

Machiavelli spent 14 years in the diplomatic corpse, during the gap between rounds of Medici rule. After the Republic fell and the Medici regained control, Machiavelli was imprisoned, tortured, released, and put out to pasture.

He wrote The Prince in 1513, after his release. Machiavelli most likely dedicated The Prince to L Medici to keep from getting his (Machiavelli’s) neck stretched. Dedicating a satire to Medici, given the immediate history, would be about the most stupid thing Machiavelli could do.

Looking at The Prince as satire would then further discount other work, specifically his Discourses on Titus Livius. At the beginning of the second “chapter” of The Prince, Machiavelli makes reference to his early work on The Discourses, telling readers to go there for discussion on Republics, as he is focusing his analysis in The Prince to that of “Princely States.”

Getting into the chronological re: The Discourses does present a problem. They were not completed until 1517 (so, after The Prince), and not published until some years after his death.

I have always read The Prince as something not to be completely taken literally. Rather, parts of it read as Disinformation. That would be entirely keeping with Machiavelli’s intellectual prowess and a desire to see Florence become great (again).

For those wanting The Prince with context, grab the Norton Critical Edition (Robert M. Adams). Runs about $20 USD.

Sir,

Excellent article about the “dirty” part of weighing best outcomes and worst outcomes when decision making.

This analysis is particularly relevant when the US, as a matter of national policy, decides to get into bed with different governments and regimes that have very different ideas about ethical conduct.

Sort of “Well, I wouldn’t do that, but if my buddy over there does it, and isn’t too overt about it, and it gets some results… I’ll just convince myself my hands are clean.”

Of course, where and how to draw that line is a subject of endless debate.

As you side, trying to find the right balance there is difficult, at best.

Mick.

Awesome article and even better discussion!

Could it be that The Prince was neither satire or a how to? But, written specifically for Medici? IOW, he wrote for a specifically intended audience and adapted his writing only for that audience.

When I was going through under grad’ and for my masters, I always checked the political leanings for my professors and wrote for that audience specifically. (And yes, I did take an inordinate amount of showers to get the ick off) I didn’t betray my beliefs, but I didn’t flaunt them either.

Does those means justify the ends? Graduated with 3.8 in both degrees, so yea.