September 23, 2015

Aaron Barruga

The tactical training industry exploded in the mid 2000’s. This period coincided with the height of the Iraq War (Petraeus’ Surge), and the fighting that took place in Afghanistan’s mountainous border with Pakistan. During this time, American media also covered the entire spectrum of warfare. Brutal house-to-house fighting in Fallujah and coalition airstrikes in Kunar were brought into the American household via the Nightly News.

Wartime coverage provided by news outlets is not a new phenomenon. However, the 2000’s brought about some of the most prolific changes to spectatorship of modern warfare through the use of social media and user generated content. Armed with a M4 and a helmet camera, hundreds of soldiers have uploaded their experiences to websites that are devoted specifically to battle focused media. Before “YouTube fame” was a common term, thousands of spectators had viewed Blackwater snipers engage Iraqi insurgents, and Delta Force Operators perform hostage rescue.

Exposure to wartime coverage through traditional news outlets and the more recent mediums provided by the Internet has altered our methods for determining source credibility. First, when an individual watches an accredited news outlet, he subconsciously creates metrics for what “right” looks like. With regards to combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, viewers create conventions that align with the following checklist: (1) The events are taking place in the desert (2) there are soldiers running around in uniform (3) I see guns-conclusion: this is what combat looks like.

Viewers then use these models and apply them to other forms of media. When watching combat footage on the Internet, the same checklist can determine what “right” looks like. The closer a YouTube video aligns with what is shown from an accredited news outlet, the more likely a viewer is to consider the content legitimate (yes, fake combat footage does exist). The cumulative effect of building heuristics to determine credibility is that we may properly construct our interpretation of what “right” looks like; or we may empower the wrong individuals and concepts.

The Rise Of Tactical Entertainment

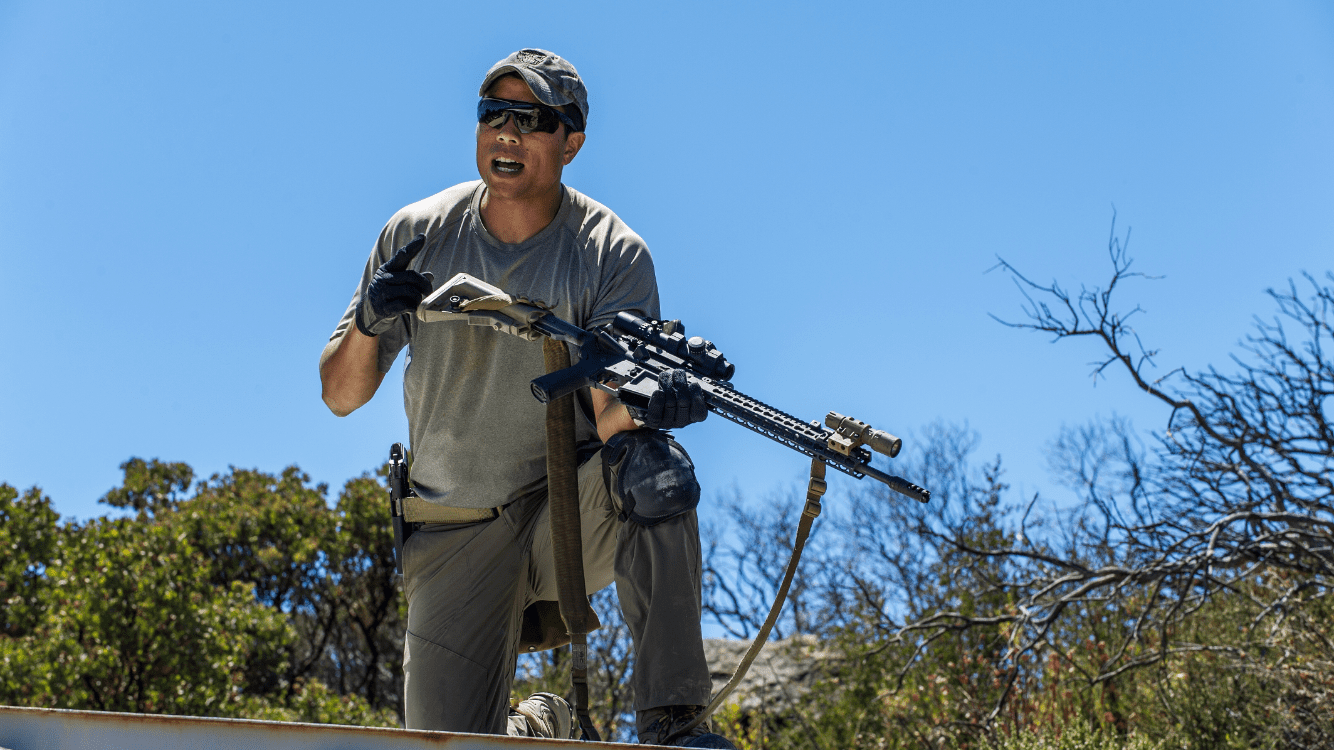

Commercial tactical instruction benefited from wartime coverage delivered by both accredited news outlets and the newer forms of user (soldier) generated Internet content. For trainers posting videos to YouTube, they only need to look like what consumers consider “right.” This task is easily accomplished by: wearing camouflage or North Face-style pants and shirts, having a cool looking gun, and most importantly-growing a beard.

Absent of robust credentials, individuals that look the part are able to build massive brands around their methodology. Under these circumstances, training begins to value flair over function, and concepts that are incompatible with fundamental skills are relabeled as doctrine. Furthermore, the accelerant qualities of social media create communal consensus. From the consumer’s point of view, how can something be wrong if it is wildly popular on Instagram? Consequently, source credibility, experience, and judgment can be measured more by social media following than real world experience.

Crossfit Case Comparison

In the early 2000’s, Crossfit exploded among the exercise industry. Individuals unfamiliar with Olympic-style weightlifting were now snatch-clean-lift-swing-battleroping themselves to exhaustion and injury. However, the prevailing mindset among Crossfitters was that pain meant growth. Unfortunately for thousands of Americans, pushing through pain meant exacerbating various forms of tendonitis.

Why did Crossfit gain robust popularity? First, Crossfit’s business model is extremely conducive to franchising. Spending $500 on a seminar to become “certified,” allows gyms to open their own Crossfit franchise. Second, the randomness of Crossfit’s programming does produce results, however, these results are not targeted towards goal specific performance. Rather than enhancing sport related abilities, Crossfit only makes people good at working out. Third, the communal effects of working out in a group formed camaraderie that made any physical activity more enjoyable due to the added social components.

Crossfit’s methodology has been challenged since its inception; however, counter-arguments were unable to gain traction due to the ubiquitous popularity of Crossfit. How can a concept (franchise) that exists globally be wrong? In the past few years, accredited news outlets and exercise professionals have vigorously criticized Crossfit’s methodology. As a result, gyms with Crossfit franchises have reverted back to being Olympic weightlifting establishments; and institutions that choose to remain Crossfit specific have restructured their programming to incorporate material that focuses on injury avoidance and meaningful programming.

Crossfit is not bad, misunderstood and poorly taught Crossfit is bad. The same holds true with tactical shooting instruction. Similar to Crossfit “instructors” that are parroting information they learned in an eight hour seminar, unaccredited tactical instructors can regurgitate information at a base level, but will always fail in expanding upon on a concept due to lack of experience.

One Sided Dialogue

Contrary to law enforcement and military organizations, commercial training is driven by what consumers are more willing to pay for. Mission success relates more to increasing profit margins than remaining honest to the fundamentals of a discipline. Distortion of knowledge by commercial firms proliferates because legitimate tactical organizations (LEO/military) do not even participate in the conversation about tactics and training. Does the marksmanship NCO for 1st SFOD-D care about what is being written in the comment section of YouTube video? No, or at least not until he retires and starts his own commercial training company.

For credible instructors, scrutinizing an unaccredited, but popular instructor is too risky.

Regardless of being right, challenging an instructor means challenging his brand and potentially alienating his client base. Moreover, challenging an individual backed by multimillion-dollar firms can expedite ostracism from the industry. Consequently, the Tier One credentials valued by government agencies to perform real world missions go undervalued in an industry driven by clever marketing and brand exposure.

A common business axiom is that you should focus less on highlighting the flaws of a competitor’s brand, and spend more effort emphasizing the strengths of your product. Although this applies to business, this concept is incompatible with academically advancing knowledge within a discipline. With regards to tactical shooting instruction, credentialed individuals should absolutely critique flawed methodology. Why-because lives are at stake.

Although social media has contributed to the proliferation of questionable instruction and tactical entertainment, it has also facilitated exposure from reputable sources. Mike Pannone of CTT Solutions recently wrote an op-ed that rigorously critiqued a pistol carry method known as the temple index. In Pat McNamara’s upcoming training DVD he frustratingly addresses search and assess methodology. Although Mike and Mac will not change the minds of the individuals that staunchly defend the temple index and search and assess, they will influence the opinions of thousands of spectators that are observing the arguments.

Compounded Effects By The Year 2020

The consequences of learning poorly recited tactical information is apparent, however, to properly understand the significance we must look at the compounded effects. Over the next few years, tactical medicine is going to be the next trend in training that gains explosive popularity. Although marksmanship-style courses will not go away, the market for this type of training is entirely saturated by both credible and questionable instructors.

Poorly regurgitated tactical medicine training poses a specific threat to patient survivability. Individuals that have been improperly trained will worsen certain wounds and injuries in such a matter that it may cause permanent damage or loss of life. In 2005, shooters highly scrutinized open enrollment tactical courses taught by individuals with questionable backgrounds. In 2015, Instagram has undermined much of the source verification process. Real world experience can now be waived if an instructor has tens of thousands of followers. At the current pace, there’s no reason to assume that tactical medicine training will not suffer the same dynamic by the year 2020.

Aaron is a Special Forces Veteran and teaches classes in Southern California. Check out his website at guerrillaapproach.com and follow him at instagram.com/guerrilla_approach