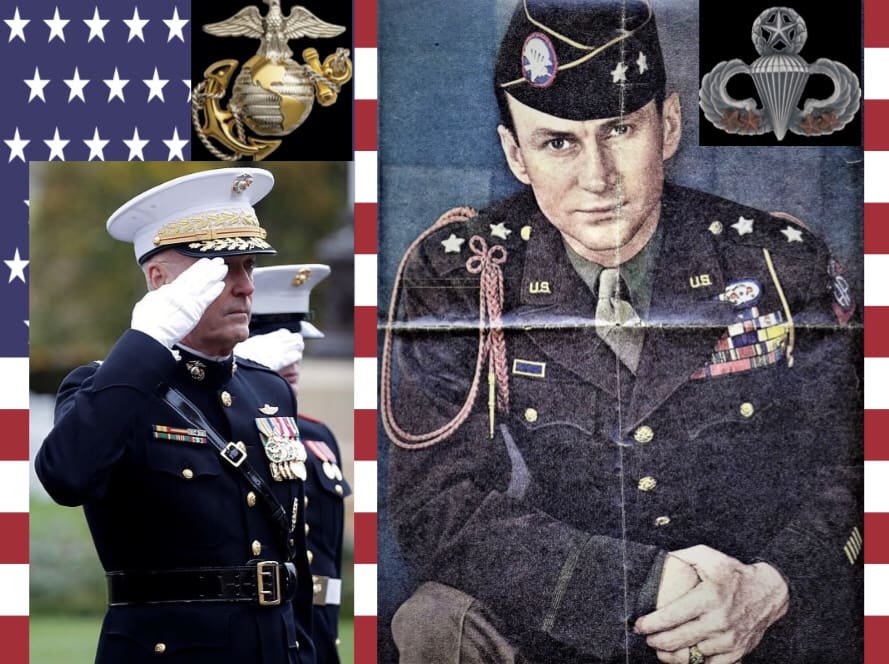

This article is about Pinks & Greens or OGs or whatever we eventually call the newly approved U.S. Army dress uniform. However, it is about larger concepts as well. When I was a lieutenant in the 2nd Bn, 505th PIR, 1985-88, I had the great good fortune to get to spend time with LTG(R) James Gavin (picture right). He had been the WWII commander of the 505th and later the 82nd Airborne Division. He made four combat jumps during the war and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) twice. During the mid-80s, he was our honorary Colonel of the Regiment. He took the ceremonial duties seriously and came to almost all of our unit events during that time. I took every opportunity to talk to him and we even had a couple of one-on-one discussions about leadership. It was an honor and an education. When General Gavin’s health began to fail, COL(R) Benjamin Vandervoort took over the duty. Vandervoort had commanded the 2nd Battalion during the war and he too had earned two DSCs. He was played by John Wayne in the movie “The Longest Day” and did break his ankle during the Normandy jump. He recovered, jumped into Holland, and was seriously wounded by German mortar fire at Nijmegen three months later.

From a professional development perspective, I have had many such fortuitous encounters over the years. Heck, I had Aaron Banks over to my house for dinner and beers when I was a Detachment Commander in 5th Group and spent an afternoon chatting with John Singlaub in the Group area on one warm summer day. Both were WWII Jedburghs and Special Forces legends. Therefore, these historical figures are perhaps a little more real and relevant to me than they may be for the current generation of soldiers. Big wars make big heroes and fewer and fewer of these giants are still with us. We may never be blessed with their likes again. I have talked a great deal about symbolism before. How important it is to appreciate and perpetuate unit histories, heraldry and special customs. These intangibles are not trivial. Instead, they are key building blocks in creating and sustaining unique group identities and unit cohesion. However, symbols only have as much power as we consciously imbue in them. If leaders teach soldiers that the service uniform is anachronistic and superfluous they will treat it that way rather than displaying the appropriate respect. Not esteem for the clothing item itself, but rather for what the uniform represents. That should not happen. Good units revere their symbols and take pride in their uniforms.

The Army has made this fundamental mistake many times. Despite having won a worldwide war on multiple continents, the Army actually suffered an identity crisis and loss of confidence after 1945. Because of the atomic bomb, there was a growing belief – even within the ranks – that traditional ground combat itself was obsolete. Rapid post-war demobilization gutted experienced officer and NCO leadership. Tiny budgets barely supported constabulary duties in occupied countries like Germany and Japan. Readiness, training and basic unit cohesion was not a priority. This leads us to Task Force Smith and the dark early days of the Korean Conflict. Marine Corps funding and state of training was not significantly better that the Army’s. However, there were considerably different levels of esprit between the Army and Marines. This disparity is evident in the retreat from Chosin Reservoir. In that campaign, Marine units maintained good order and performed notably better than many Army units. It was not gear or tactical training that made the difference but rather a shared unit identity and stubborn pride that proved to be the critical factor. Make no mistake, symbols like the Eagle, Globe and Anchor (EGA) and the uniform of a Marine only mean something in combat because the Corps makes the concerted effort to give those items significance and power.

Unfortunately, the brutal but ultimately indecisive Korean Conflict did nothing to reestablish Army confidence in itself. Rather, the “lesson” of Korea was that the early and widespread use of atomic bombs would be necessary to avoid any future, similar strategic stalemate. Therefore, the Army decided it needed a new “modern” identity. That in turn meant discarding prominent symbols of the old Army. The Army dress uniform or “Dress Greens” that most of us grew up with was one of the misguided results. That new dress uniform was deliberately cut in a business rather than martial style. More obviously, the color had no historical connection with any previous Army uniform. Furthermore, although there was still conscription, the Army began – for the first time – to sell itself to the American people as a job rather than a profession. It was a huge mistake precisely because it erased a strong identity and replaced it with a muddled professional ethos that was inferior and less resilient.

The Army has an unfortunate habit of forgetting history and disregarding heraldry because, I suspect, there are too many people who do not think it is important for combat readiness. Those people are wrong. On the other hand, the Marine Corps has been exponentially more successful in avoiding similar identity pitfalls. For example, on the left side of the picture is GEN Dunford, the current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, visiting Belleau Wood this last week. While his uniform is perhaps not identical to the early 20th Century Marine dress uniform, it is close enough that a WWII Marine would instantly recognize it, as would just about every American – and many people in other countries around the world. Are dress uniforms important in shaping that desirable and unbreakable unit identity? I say yes. However, one need not take my word for it; the evidence is clear that the Marine Corps’ leadership thinks so and has thought so for generations.

It is no coincidence that the American people have much more difficulty in identifying their own soldiers. The Army has done a bad job of establishing an enduring “brand” or strong collective identity like the Corps. It is sad but all too true. The Army has had a strong sense of distinctiveness in the past, most notable during the post-Civil War period (1866-1898) and the post-WWI period (1920-1940). Both time periods saw an all-volunteer but woefully underfunded Army in which a career was no less than thirty years and selfless service was almost a given. The first era was indelibly shaped by leaders like Sherman and Sheridan and gave us the classic blue uniform. Leaders like MacArthur, Marshall and Eisenhower left their mark on the second while wearing P&Gs. It is only fitting, in my opinion, that we reestablish a link back to the uniforms of that period.

Some argue that because less than perfect or even bad decisions have been made about uniforms in the pass we must now forgo making any future decisions. Nonsense. When it becomes clear that a decision is not achieving the desired result it is the obligation of a leader to make a correction. Many of the mistakes in this arena were made in the name of cost cutting in one way, shape, or form. The Army has always been penny wise and pound foolish. Probably that is because the return on the investment in symbols and esprit de corps is only discernable in the toughest of situations. Others argue that dress uniforms have no utility because they are not worn often enough to be “cost effective.” Since when has the intrinsic value or the symbolic power of an item depended on frequency of use? Take the American Flag for example. It is unquestionably one of the most powerful symbols of our national identity. It has always been with me – whether it was visible on my uniform or not – because I have long since internalized its meaning and power. When going into battle, soldiers now wear it on our sleeves while Marines do not. Yet it accompanies and bolsters the resolve of all of us – visibly displayed or otherwise. A dress uniform may not get much use but it should nevertheless mean something when it is worn – no matter how infrequently.

Other times the Army has been driven by some vague sense that we needed to discard history in order to effectively move into the future. Wrong again. Service and Unit histories are cumulative, built over generations, and become more powerful over time. We do not shake the etch-a-sketch, erase unit histories and start over after each conflict. A point I tried to make about the 5th Special Forces Group Flash some time ago. Except for the 82nd, none of the WWII Airborne Divisions had a history. None of the 500 series Parachute Infantry Battalions or Regiments had a history. Leaders recognized the need so they expended a great deal of precious time and energy to build a collective identity. Mostly that involved symbolism. Jump Wings were essentially the paratroopers EGA, and jump boots clearly set him apart from all other soldiers. Moreover, creating that mystique was not a training distractor but rather essential in preparing those soldiers to prevail in combat. Today, Jump Wings and bloused jump boots may seem inconsequential and even unnecessary in a peacetime garrison environment, but they meant a great deal at Bastogne. Ask any man who was there.

I admit I have been surprised about how many people have waxed nostalgic over the old Dress Greens. By my recollection, from day one people were constantly bitching about how unmilitary they looked and especially about the god-awful color. As early as the mid-70s, surveys consistently showed that soldiers would have preferred to re-adopt a P&G type uniform. Several times, including the mid-80s, there was even serious movement in that direction. Instead, the Army doubled down and made the situation worse. First, as a cost saving measure the Army stopped issuing the well-liked Khaki summer Class-B uniform; then replaced the tan shirt – the last vestige of the older era uniforms – with a blue-green version also without any historical precedent. The last major decision that converted the Dress Blue, formal uniform, into the ASU actually ruined two uniforms at once. Kluging the purposes and the heraldry of both into a hybrid that serves neither purpose well. The blue pants and white shirt of the ASU make a particularly unflattering Class-B uniform. And it does not help unit cohesion that there is an accommodation for a wartime service unit badge on the ASU pocket, but no place for the current unit of assignment.

However, even now the situation is not hopeless. It is up to leaders. Uniform items can mean everything or nothing. The Green Beret for example is just a piece of dyed wool – but just try to take it away from someone who has earned it. The Airborne Maroon Beret was not important until GEN Rogers took in away in 1978. The Airborne community made their displeasure known until they got in back in 1983. If berets are not important, why are people still re-litigating the Ranger Beret decision twenty years later? These pieces of headgear are significant – as are badges, tabs and unit patches – but only in as much as they are a visible reflection of the unit’s identity and character. Unfortunately, as we all know, the Army failed to give the black beret any power when it became standardized service headgear. I expect better results from the P&Gs simply because they do reflect history, are indeed iconic, and the American people can actually tell that it is the uniform of a soldier.

As to the question of cost, a new dress uniform purchase – of any flavor – can be a considerable individual expenditure. However, in the time between announcement, availability and required to have dates, soldiers have the opportunity to plan and budget for the eventuality. Many soldiers need not worry at all. Approximately 75% of soldiers get out after one term or less, 50% of officers leave after completing their initial obligation. Because these uniform changeovers are deliberately spread out over years the majority of soldiers will never need to buy the new uniform and will leave service with whatever they were initially issued. Even if that were not true, I think the current Army leadership has made a decision that is good for the service. They have reembraced storied organizational history and it is long overdue. In fact, I would like the Army to go faster and further and issue P&Gs to all soldiers RFI style – the sooner the better. Moreover, it should come with a pamphlet that outlines the history AND the Army should pay for initial fittings and additional tailoring every three years or upon promotion to sergeant and each grade after. It would be a small investment that could pay huge dividends. I also look forward to ASUs reverting to a cleaner formal “Dress Blue” status. No doubt P&Gs will provide a more suitable and professional looking Class-B configuration as well. In any case, the Army will only get out of this uniform change whatever leaders put into it.

Bottom line: Do I think a modern soldier – commissioned, warrant, noncommissioned or enlisted – can and should be proud to wear a dress uniform reminiscent of those worn before and during WWII thru Korea by leaders like: James Gavin, Matthew Ridgeway, Reuben Tucker, Robert Frederick, Aaron Banks, John Singlaub, Lewis Millet, Hal Moore, Audie Murphy and William Darby – just to name a few? Damn right I do.

Administrative addendum: Earlier discussions on this site about this subject has been contentious at times and frankly overly personalized. We have all – myself included – resorted to ad hominem attacks when we are angry. I have said it before and will say it again; in adult and professional debates, smearing an opponent’s character does nothing to strengthen an argument, provide evidence in support of a position, or prove a point. Another thing, I am the soldier I am today because of NCOs. I actually sought a commission on the advice of an NCO. I came out on the SFC promotion list at just nine years of service (which at the time was fast for infantry). I was feeling confident in my enlisted career prospects at that point. My First Sergeant sat me down and gave me a different perspective. He said, “You are doing great. In four years, you will probably have my job. Or, in four years, you could be commanding an infantry company. I think you would be good at that too. Which would you prefer?” I thought about it and decided I was more intrigued by the challenge of command and dropped my OCS packet soon after.

In doing so, I benefited from the full support of my chain of command, NCOs and officers alike. These were the kind of professionals I grew up with and admire. They reinforced what I had always been taught. NCOs and officers are teammates and partners in building and leading units. I have never had time for anyone who – for any reason – cannot be a teammate deserving of full trust and confidence. I have done some things in my career, drunk and sober, that are worthy of a reasonable amount of ridicule. I have made more than my share of bad decisions that merit being called out. Good teammates – of all ranks – have consistently done that for me when necessary; and I am the better leader and person for it. While there has been a very few occasional exceptions – the odd bad leader – I have served in units where the relationship between almost all NCOs and officers has been one of mutual respect and shared purpose. That should be the standard. NCOs denigrating all officers or officers disparaging all NCOs is unhelpful, unprofessional, and unnecessary. Good leaders do not do that. It is never “us versus them” in good units.

Finally, I would never have the audacity to equate my service to those who saw combat in WWII, Korea or Vietnam. Those stalwart soldiers participated in engagements of a size, scope, duration, hardship and danger well beyond anything I ever experienced. However, I am confident enough that the length and girth of my professional “resume” is adequate when compared to most soldiers that have served since Vietnam. Not the longest or the most impressive…but not embarrassingly small either. So – although I do not see any sense in it – if someone feels any compelling need to measure his resume against mine to judge who is or is not a “real soldier,” I suppose we can go down that rabbit hole. However, I would prefer a more productive and reasoned discussion. I expect that a good number of people may take a divergent or even opposing position from mine. That is fine. I will not question your intellect, professionalism or your integrity just because we disagree. I only expect the same in return.

De Opresso Liber.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

As always, Terry Baldwin lays the truth out plainly.

I dislike the uniform change, but his clarity is effectively the last word. Hope the Big Green listens to the tailoring and educational guidance laid out.

Damn well said Sir. Damn well said indeed.

“In fact, I would like the Army to go faster and further and issue P&Gs to all soldiers RFI style – the sooner the better. Moreover, it should come with a pamphlet that outlines the history AND the Army should pay for initial fittings and additional tailoring every three years or upon promotion to sergeant and each grade after. It would be a small investment that could pay huge dividends.”

Word.

This tailoring is also an unspoken reason why the Marines typically look good in their dress blues: the uniforms are tailored, not off the rack. Having a tailored uniform would do a lot to improve the image of the soldiers as well as having some pride in the uniform. And once a year you’ll have to be sure you fit in the uniform…weight standard forcing function if there ever was one.

Great write up-

In my time in the Army, the “Class A” uniform (which is how we referred to it) played little to no significance. Early in my career in the 75th, we wore the “Class A” uniform at the Ranger Ball, that was it. I was smoked for hours each time it was inspected and a “deficiency” was noted prior to my first Ranger Ball. I may have worn it 3-4 times while serving 8 years in the Regiment. I took pride in wearing it.

Later, in CAG, I wore the “Class A” three times for DA photos. Three times in a span of 12 years. That was more or less a chore for promotional purposes- served no real purpose other than a once every few years haircut, shave, and making sure that the salad on my uniform matched that of my records.

While I appreciate the nostalgia and historical significance of all of the uniforms I had the privilege of wearing, it may be difficult for many to “bond” with the dress uniform because it was never significant during their time in service. I think that’s why so many are at odds with the new Pinks and Greens- just my two cents.

Darkhorse,

Certainly true. I would never suggest that uniforms are the most important or only leg that supports a unit’s identity. Nor should they be. But they are a more important component than I think some – including the Army itself – recognizes. I am sure you would attest that the units you mentioned do a good job of inculcating the unit’s ethos in new people. Moreover, I think you would also agree, people that do not internalize those organizational values – and live them – either don’t get in or don’t stay long.

I only wore various Class A uniforms occasionally during my service as well. Up to and including the ASU configuration. In the last few years it seemed like I only wore them for funerals. Thankfully not that many, but I cannot think of a more significant purpose for wearing a dress uniform. And each time, in every uniform, I was proud to represent SF, the Army and the Nation itself to the family of the fallen. Well worth what I paid for the uniforms and then some.

The Corps tells their recruits from day one that it is privilege to wear the uniform of a United States Marine. Every serving Marine I have ever met believes that. And, from what I have observed, they tend to act accordingly. I think that is a good thing. That example, and the Army’s own history, leads me to believe it would be beneficial if more soldiers felt the same way about our uniforms.

TLB

I agree with you wholeheartedly. I am merely attempting to share why I believe others don’t like the recent change/update/upgrade from one dress uniform to another. I think many have likely worn one or two times and are going to have to switch again. I would be beyond annoyed having to purchase yet another option while hardly ever wearing another. Thanks again for the article, Terry.

1. Fully support the new Greens. Absolutely. Will make the Army recognizable again.

2. Think the Army doesn’t honestly wear their service uniform enough. In WWI / WWII it was so recognizable b/c Soldiers wore their dress or service uniform all over the place. Now soldiers are looked down upon if they mention wearing a service uniform.

3. Sometimes the Army puts so much focus on identity it actually harms recognition and pride. There are so many random unit patches and crests I see that

3. Sometimes the Army puts so much focus on identity it actually harms recognition and pride. There are so many random unit patches and crests I see that I can’t even identify (generally sustainment or CSS units). Unlike the major BCTs/DIVs which are instantly recognizable, these units are not and many of their own Soldiers aren’t even familiar with their own patches history or symbolism much less take any affiliation / pride in them. Makes it easier for the USMC since all their Soldiers can affiliate with an EGA.

*Marines, not soldiers. Fixed it for you. 😉

Agreed absolutely.

One area where Army gives itself a pass is allowing wear of the utility uniform in environments more appropriate for what we once called the Class B or even Class A uniform. I attend a multi-agency working group where Army is the ONLY military service in its utility uniform. And we’ve gone even further, creating the “low signature” duty uniform of unit polo and 5.11 pant. You know, because OPSEC.

LTC Baldwin, your arguments would be more compelling if there was any indication at all that the Army would learn from your essay and their past mistakes….

We can speculate on the odds of that happening.

My own (primary) service, the US Air Force, has made many of the same choices and errors…..but without the history, except that inherited from the Army… But the change from our own blue service to the abortion inflicted by McPeak, and then made slightly less offensive, but suffers from the same deficiencies the Army choices have suffered.

Even the emblem of the AF has changed 4 or 5 times in the last 30 years…..I have no idea what it is that Airmen are supposed to believe in these days…

Quite. When the AF announced the swap to OCPs I posited keeping enlisted stripes on the sleeves as a connection to enlisted heritage. We always had them there in our utility uniforms and never went to collar chevrons like the other services. Unit heraldry could be supported with the so-called “operator” hats sporting unit patches which are nothing more than a churched up ball cap that is itself not without precedent not only in the AF but other services as well. Yes, stripes would have to be resized. And? Or, TSgt and below on the sleeves, MSgt and above on the chest. Not without precedent again, SNCOs used to wear epaulet rank in the service uniform. What about in body armor? You wear a combat shirt and appropriate insignia.

The AF constantly tries to reinvent itself as the “newer and younger” service with all the whiz bang toys. Speaking of emblems, the AF coat of arms tie tack I got in BMT in the 90s was quickly replaced with the Hap Arnold winged star which was shortly replaced thereafter with the stylized, modern version and now who knows what is current. The metallic EGA stickers the Marine recruiters hand out haven’t changed in over 30yrs, we can’t figure out a tie tack.

People decried the “Billy Mitchell” style service dress test article with the high collar but I saw an actual, smart military uniform that called back to a founding father of our service. There is plenty of history to draw from and be proud of but no one is taking a look.

Good points

I won’t miss the sleeve stripes at all

LTC Baldwin once again hits the 10-ring.

Every military problem is, at its core, a leadership issue. Good leadership is also the solution to every military challenge.

Historical Army uniform silliness is reflective of leadership problems, as is the institutional resistance to maintaining Army lineage. The ever-changing uniforms are just a symptom of the disease, not the disease itself.

Army leadership tends to focus on new and shiny things, believing that trotting out new and shiny things will fix what ails the Army…ignorant of the fact that the ailment is leaders fixated on new and shiny things as solutions.

Sometimes the new shiny thing is a new felt hat for everyone, other times it’s a new MACOM parked in Austin, or a new unit that trains foreigners…or a new APFT.

Fortunately, there is a cure to what ails the Army. The cure is good leadership, starting at the top, leadership that demonstrates that standards are applied evenly without regard to rank or patronage. Leadership that instills confidence in the force. The hard part is finding leaders that are up to the challenge. They are out there, but the Army has been chasing them all away.

DOL,

JMG

JM Gavin,

I agree. I do think they are many more good leaders out there than not. The trick is not just to simply retain them but also to empower them. Unfortunately, the Army struggles and consistently comes up short in that area as well.

TLB

a good article, but the claim that the Marines performed better than the 31st RCT at Chosin is not clear cut. The Army regiment on the East side of the reservoir was mishandled by higher leadership – a thrown tegether unit urged to advance more quickly than was wise. It was also much smaller than the Marine division on the West side of the reservoir. Unit cohesion did break down but only when nearly all the leaders were killed or wounded and the ammo depleted…before that the 31st Rct was outnumbered 6 to 1 and killed 4 to 1 of the enemy. only about 10-12% of the regiment was alive and uninjured after they were overwhelmed. They fought themselves to death.

A A Ron,

Good points. I think “not clear cut” is a good way to say it. Since most of the senior leaders like MacLean (sp?) and Faith were killed in the process, we may never know exactly why certain decisions were made. Like why the units of the 31st were initially so widely dispersed as not to be mutually supportive. Which allowed them to be isolated and defeated piecemeal. And why did it take MacLean so long (2 days) to react in any meaningful way to the overwhelming Chinese threat. By then it was too late.

I do not claim to be the definitive source for any period of military history. So, I did some quick checking. In 2000 there was an effort to give the soldiers who fought at Chosin recognition by way of a Presidential Unit Citation. I think this is what Moustache 6 (below) is referring to. But even the citation itself says that at Chosin the 31st was a “unit” in name only. It was a cobbled together collection of poorly trained soldiers with almost no experienced company grade officers or senior NCOs.

And as you say, they were markedly ill-served by their senior leadership. The Marines, on the other hand, had the experienced leadership and simply did not suffer from those same problems. I have nothing but the highest respect for anyone and everyone who fought there. But as a professional soldier looking at it objectively, I have to conclude that the Marine Corps did a good job and the Army did a bad job of preparing their respective forces to succeed – not just survive – on the battlefield.

TLB

East of Chosin by Appleman goes far in correcting what has passed for the popular telling of how the Army performed at Chosin. I had the privilege of knowing and speaking with the 502nd’s honorary colonel who served there after his service with the 502nd in WWII and was adamant that there was no comparison between his experience in WWII and what the 31st RCT faced at Chosin.

Had the 31st RCT not held for days against numerous Chinese divisions that even included armor the Marines would have faced those divisions and done so without an airfield to resupply and evacuate wounded. A little known fact is the 31st RCT proportionately engaged more enemy with a formation 30% smaller (even smaller if you consider the 30% ROK draftees who largely abandoned their posts) and inflicted more casualties than any similar sized Marine unit. Further no Marine unit suffered the loss of almost every officer and senior NCO down to the platoon level.

The Navy has gone out of its way to recognize the service of the 31st RCT who with their absolute destruction in detail made the Corps historic withdrawal possible. The continued disparagement of the 31st RCT is one of history’s greatest sins. There’s a reason the Commander was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Many Army units did not react well to the Chinese formal entry into Korea. Unfortunately the 31st RCT seems to get thrown into the mix likely because of their proximity to the Marines who did an excellent job. A thoughtful unbiased study of the battle East of Chosin reverses most if not all preconceived notions. Even a quick read of Task Force faith on wiki is a good start.

Will,

As I said earlier, I mean no disrespect whatsoever to those that fought there. My critique, which even the Army’s own official history acknowledges, is that the U.S. Army initially deployed units like TF Smith and the 31st that were undermanned, underequipped, poorly trained and – most importantly – critically short of leadership at the small unit level. These units were failed by the organizational / institutional Army which was the only point I was actually trying to make.

While I was at Leavenworth (98-2000) I read several of Appleman’s books, “East of Chosin,” “Disaster in Korea,” and “Escaping the Trap.” Also Toland’s “In Mortal Combat,” Fehrenbach’s “This Kind of War,” and Blair’s “The Forgotten War.” I did a couple of papers on Korea while at CGSC – although none specifically focused on Chosin. All those books are still sitting on my bookshelf and I recommend them.

It is true that at Chosin individual soldiers displayed valor and tenacity and endured unimaginably hardships with honor. All Americans can be proud of that. However, I do not think that can mitigate – and certainly does not absolve – the Army, MacArthur’s HQ, the 10th Corps or even the TF senior leadership from their culpability for this massacre.

It is also true, as you say, that the 31st bought the Marines time and attrited the enemy thru their sacrifice. In hindsight we know that now. They did not know that then. Neither delay or attrition was ever the mission – or the intent – of the 31st’ leadership. They were simply fighting to get out of a trap and moved as quickly as they possibly could to break contact and reach a more secure position held by the Marines.

Again, no intent to disparage anyone on my part, but those do still appear to be the basic facts.

TLB

Terry never said you were trying to disparage the 31st. It was a general comment as history for a long time portrayed the 31st in the worst light. A since discredited Navy Chaplain’s description of the survivors of Chosin were at the heart of that story and it has been repeated and stuck for a very long time.

I disagree a bit with your characterization of all Army units around Chosin. There actually weren’t many besides the 31st as I remember and all but one (the missing 31st BN) were company sized or smaller. Most Army units in the area not wiped out became part of the Marine’s withdrawal like the tanks sent to support the 31st that the Marines integrated into their defense. I think if you compared the Marines at Chosin across the whole Army’s withdrawl in response to China’s entry you’d have several stark examples to support your point vs your stated sample of Chosin.

Disagree that the 31st was critically short leadership at the small unit level that is until they were killed in combat. They weren’t necessarily undermanned. The battalions were full strength (with ROK draftees) they were missing a battalion though. Maybe the correct term is undertrength? As for leadership, I agree with your assessment from Maclean and up. Battalion and below acquitted themselves well.

Wholeheartedly agree on your comments reference Mac and 10th Corps, just criminal.

For all of TF Smith’s failings, any unit equipped and tasked as TF Smith was would have failed even if every soldier was from Delta. No amount of training would have enabled six 105 howitzers, a half battalion without AT weapons and no air support with stopping two regiments (10-1) of tank supported infantry.

I believe you made outstanding and entirely accurate assessments of the Army’s bigger mistakes and for brevity’s sake weren’t able to connect the dots down to the impact at the battalion and below level. The problem though is many people don’t know the story at the battalion and below level and it leaves the impression that the rot is all the way through. The 31st RCT is a poor example to use as a failure of leadership though the decisions that got them there which were made at higher were classic examples of gross leadership. LTC Faith knew that when he dropped a handful of medals in the snow after being decorated by the division commander who flew in and then out of Chosin with little care about the life or death fight that was occurring.

All of this is minor to the excellent points you made reference uniforms, instilling personal pride and creating a sense of cohesion that the Army does at unit level instead of across the force.

Will,

I agree that there were a number of examples of less than stellar performance by Army units during the initial Chinese intervention. Of course, relitigating the Korean Conflict was not my focus or intent, so I did not single out the 31st – or any other unit – in the article. The conversation just went that way. I also agree with your previous comments that the 31st was unfairly singled out for criticism without appreciation of the full context of the tactical situation.

That is a continuing challenge with these short articles. I try to make brief – and admittedly shallow – historical connections without delving too deep into the larger complexities, ambiguities and nuances that are always involved in historical events. Hopefully, as happened this time, the discussion can fill in some of the blanks I leave behind.

TLB

I always look forward to LTC (Ret) Baldwin’s observations.

I think this is his best to date.

Excellent post, thanks for sharing. Hopefully that will quiet the naysayers a bit. Though if the Army wants to connect to its heritage, I hope it will walk back its “encouragement” that the uniforms be referred to as greens rather than pinks and greens.

It is a shame that the Army adopted Scorpion rather than Multicam proper. It could’ve chosen the better pattern, and the one that a generation went to war wearing. Instead, it chose the pattern’s prototype, the one that won the contest in 2004, the one that should’ve been adopted in the first place. It reflects poorly on them as an organization, like a big reminder of Army incompetence that every soldier wears.

Lose_Game,

It is true that military leaders have an obligation to be good stewards of taxpayer provided funds. However, it is just as true that the cheapest solution is rarely the best solution. I have found that any decision based primarily on “saving money” is almost inevitably a bad decision.

TLB

Well-argued and cogent, making a better case than the guys still on active duty are making. I’m almost reconciled to the idea, after reading this.

But, I’m still sitting here with that little voice in my head going “Here we go again–Yet another iteration of Shinseki’s Syndrome…”.

Maybe this time will be different, and the uniformed bureaucrats will manage to do something with a uniform that isn’t actually detrimental to the morale and esprit de corps of the actual living, breathing Army. After living through the morale-busting embarrassment that was the black beret fiasco, and watching the same sort of ginned-up enthusiastic portrayal of the way the new ASU was going to fix everything, well… I’m cynical and untrusting. These people manifestly do not know what the hell they are doing.

I don’t think the people running the Army today actually know how the hell it worked in the past, works now, with all their asinine little changes, or have a good idea of how to make it work in the future. The uniform issues are just a symptom; LTC Baldwin rightly points out that the AG uniform we all referred to as the Class “A” was partially adopted back-when as a New Coke-esque attempt at rebranding the Army, and pretty much failed. Remind anyone of a multitude of other recent brilliant ideas, like the black beret or the ASU…? Doing the same thing repeatedly, and expecting different results is commonly defined as…? Yeah; insanity. We has it, in this regard.

And, the old Greens failed for a lot of the same reasons I fear that the P&G uniform is going to fail, because they’re going at this crap that they’re trying to address with it, that of “brand and identity”, via the same purblind idiocy that Shinseki imposed on us with the black beret. You do not fix fundamental issues with identity and “branding”, a term I really loathe in this context, by issuing a shiny new uniform item.

The root problem isn’t in the uniform, it’s in the goddamn Army culture itself, how we do business, and we’re not even beginning to address the very real and very basic issues–Mostly, because we don’t even recognize them ourselves. We’ve all been swimming in this murky water for so long that we don’t ever recognize the problems, or what was changed from the ways of the past that actually, y’know, worked.

Let’s examine the real issue here, which is that whole “brand-and-identity” thing. The Army is abysmal at that stuff, because we make decisions about manning, unit establishments, and all the other things that actually go into creating and maintaining the Army “brand-and-identity” in a state of willful ignorance. The uniform isn’t the problem–The problem is how we do ninety percent of our daily business.

Where the hell is the connection with the new soldier with his unit? How can you build “brand-and-identity”, when ninety percent of your units are treated as disposable abstracts? Where the hell is 24ID, these days, anyway? What happened to the 9th? Where is there any emphasis on teaching tradition and history in the training base? The Marines learn Marine history almost as a sacrament, throughout initial entry training. We do it, if at all, as an afterthought. I guarantee you that the majority of junior enlisted in the Army only bother to look up unit history if they’re going up for Soldier of the Month, or something similar.

The unit I had the strongest connection with over the course of my career, which was the 15th Engineer Battalion, was shut down for convenience’s sake back around Desert Storm. How the hell am I, as a private soldier, supposed to develop an identification with my unit or my Army, when my unit, my fucking home, is treated as some administrative abstraction, and willy-nilly destroyed because it didn’t fit in the all-sacred, all-holy plan? That was my goddamn home, my community, my family, and the Big Army assholes just kinda casually shut the place down, one day, in an absence of mind? WTF? You want me to identify with an entity that does that shit to my nearest and dearest?

And, there are a lot of people out there in the Army who are gonna be thinking “What the hell is he going on about…? It’s just a unit… We got lots and lots of those…”.

Which is the ‘effing problem, right there–We’ve institutionalized anomie and disconnection, along with mediocrity and mendacity. I’d be willing to bet that most reading this, if they bother, will simply not “get it”–And, those are the ones who are also going “Oh, cool… Keen new uniforms!”.

Doesn’t matter what you put us in, the underlying problems are still going to be there, and just like with the beret and the ASU, they’ll still be there when all y’all come up with the next bright idea in this arena.

And, I’m supposed to identify with the larger organization that casually wreaks this destruction on my home and the community within it? Really? Do people really think the bonds are between individual and the abstract Army, as opposed to between individual soldiers and their low-level units?

You get down to it, I could really give two fucks and a damn for the abstract idea of the “Army”. I served for the men on my left and right flank; my unit, my leaders, my friends. And, the goddamn Big Army? It constantly strove to destroy or break up those relationships. That’s the root problem, right there–We treat human beings and the relationships they develop as though they were so many spare parts and fungibles. We’ve done that with unit identities and histories to the point that I don’t even really understand why we even bother with having colors and guidons, any more. They are, sadly, essentially meaningless. What soldier today would identify with his unit colors enough that he’d die to keep them out of the hands of the enemy, as Lieutenants Coghill and Melvill did for the 24th Foot’s Queens Colors at Isandlwana?

Most of them would probably walk right by them on the way out of the building, after hearing the fire alarm go off. And, why is that?

Because the Army is inept as all hell at building cohesive identification between the soldier and his unit. Until that gets addressed, the friggin’ uniforms are merely costume.

That’s a point that Shinseki failed utterly to grasp; to the Ranger Regiment, that black beret was freighted with meaning and the Rangers were rightly connected to it. It meant something to them. Taking it, and handing it out to the rest of the Army basically severed that connection, and since there wasn’t a connection for the rest of the Army to anything meaningful, he turned a valuable unit symbol into… Costume.

Putting that thing on didn’t make me feel like a better soldier, it made me feel like some Stolen Valor faker. I still remember the distaste I felt that day, for the order we were given, and the inept fools who gave it to us. I honestly don’t think there would have been any way to fix that, either, and make any of us “legs” feel right about wearing that beret–I’ve been around too many guys from Ranger Regiment that I respected to have ever been able to wear that thing without having done exactly what they did to actually earn it.

And, the fact that Shinseki and his staff could do that, not understanding the actual effect of the whole thing on all of us, Rangers and line dogs? Blows my mind, to this day–How can anyone at that rank and time in service have been that goddamn blind?

The whole treatment of our historical units, and how we just “assign” colors and unit identities by deactivating in Germany, and reactivating on some post back here stateside is symptomatic; there’s just about zero continuity to the whole thing: One day, you’re PFC Smith in the gloried and honored 1/23 Infantry Battalion, and the next, some jackass comes along and tells you that, no, instead, you’re in the 1/15 Infantry, and you need to learn a whole new unit history… If you’re even gonna bother; after all, they’ll likely make you 2/27 next week, or you’ll PCS soon.

What. The. Fuck? Seriously? You expect the troops to bond and identify with a unit where you just gratuitously FedEx the colors back from Germany to them…? Where is the personal connection? The continuity? You don’t even have the courtesy to fly ’em back, escorted by the then-current CSM, who might bring along with them a healthy dollop of corporate identity? “Here are your new colors… Let me tell you about them, and the men who served under them… In their names, I entrust them to you… Carry them with honor.”.

We can’t even be bothered to do that, leaving the actual details of the unit identity as mere ciphers in a seldom-read book the CSM might have in his office. It’s like unit identities don’t even matter, or something…

And, the troops see this casual attitude, and respond appropriately. The colors get FedExed? Sure, we’ll treat them with a similar cavalier attitude, too. It’s abundantly obvious to all of us lower enlisted scum that our units, which I repeat and reiterate for those blind to that fact, are our homes, communities, and brotherhoods… Well, they are meaningless to the faceless bureaucrats that run Big Army. So, guess what? There’s no point in investing yourself into the “brand and identity”, when that’s how it’s going to be treated.

And, y’all think you’re gonna compensate for and fix this whole thing, by issuing a new uniform? It is to laugh.

This is what pisses me off about the uniform issue, when I think about it: It’s an utterly inept attempt to fix issues that arise out of the impersonal and arbitrary way we do this sort of thing, and IT ISN”T GOING TO WORK. You’re going to change the clothes we wear, and that’s it.

The substantive and very real problems with identity, morale, and cohesion? Just like with that idiot Shinseki’s beret “initiative”, those fucking issues are still going to be there, effectively unaddressed. The clothing we wear is utterly meaningless, when there’s no real substance or connection to what’s supposed to be behind the symbology of what they represent. Symbols only have the meaning we assign them–If there is no connection between the man, the idea, and the symbol, then they’re meaningless and without truth.

Who the hell cares about the 291st Engineer Battalion, the men who arguably stopped Joachim Peiper cold during the Battle of the Bulge? Today? Nobody–Because that unit is dead, killed by the Army, which saw no value in keeping it on the active roll. Their unit crest is meaningless to a modern soldier, because there is no real connection for them to it, or anyone who served under it. They could stand that unit up tomorrow, and all that history would signify to the troops in it some more trivia they’d need to memorize for Soldier of the Month boards. A few of us might look at that history, and feel a twinge of connection and unit pride in what the guys in it during WWII did, but we’d be the weirdos. And, why? Because the Army is constantly and actively severing all of the ties between individual soldiers and their units. All the time. The last stab we made at “fixing” that issue was CARS, and we all know how well that worked out. Just like COHORT.

The basic problem here isn’t the uniform; it’s the impersonal and completely back-asswards way we do everything related to all this vitally important “cohesion and morale stuff”. Starting by changing the uniform, yet again, well… That’s just more of the same inept top-down BS that Shinseki tried with the black beret. The actual problems start down at a much lower and far more intrinsic level, where we “soldierize” civilians and turn them into members of our organization. You do the analysis of it all, and the disturbing thing to realize is that there are street gangs and religious cults out there that have a better grasp on how to do this “stuff” than our Army does. You’ll never see the Hare Krishna types saying “Well, we need better identification with our brand, so let’s do some focus groups on picking a different robe color…”.

But, that’s basically what we’re doing with this whole uniform changeover crap. If you’re sitting in the Army, and look up to notice your bosses are treating things like this as though they were Ford looking to put together another ad campaign, well… If you’re not disturbed by that, you’re not too well connected yourself with what bonds soldiers to one another and their units.

I hate to say it, but the fact is, this “initiative” (Lord, how I hate that buzzword…) ain’t going to fix the fundamental problem that they’re groping towards fixing with it. And, because of that? They might as well put us in gray jumpsuits, for all the good the fancy new duds are going to do for addressing those “fundamental issues of identity and branding”.

I really don’t think that the people running our Army have a goddamn clue what motivates people to be soldiers, or what to do with the ones they do manage to motivate by accident. If they had, I seriously doubt they’d have shut down AKO for retirees the way they did, and the rosters of our active units wouldn’t look like someone was playing musical chairs with the guidons and colors…

Damn…

I never really saw that side of the institution. I was blessed to serve in an ARNG unit with very deep roots that maintained an incredibly deep roots in it’s history and a point of pride in it’s heritage. Where I knew of E4s who went on to be the state CSM and, now looking from the outside, see my former PFCs who deployed becoming unit leadership as NCOs.

We knew the history of the unit and prided ourselves on carrying the torch in our unit’s specialty. To the point where I switched services and STILL consider our company insignia, official and adopted, to be a point of pride in my office. Where even though the AD/ARNG partnership has replaced their SSI, the old unit SSI is a known and reverenced piece of the heritage.

I’ve always been told “the USMC prides itself on the service, the Army prides itself in the unit”. It makes me sad to know I had a rare experience in this context. That the Army more often than not regards its units as disposable. I guess I’ve been fortunate to have been in an “incestuous” National Guard unit where even when culture has added and changed the roots remain firm.

The National Guard does it differently, and I think, better. At least, with regard to the whole “identify with the unit” aspect. Even when the idjits up at the Guard Bureau willy-nilly decide to re-mission the unit, and change the entire branch from one thing to another, the unit’s cohesion remains. I recall dealing with one Artillery outfit that re-flagged and re-classified as an Engineer outfit, and they were basically still the same unit with the same people, just re-trained. They made it work, and it was interesting to observe, because the unit cultures were so different between branches.

Some aspects of the whole thing I’d like to see Big Army take up, but making it work the way the Guard does it? It would probably break down on the details. And, in a big-picture way, might even be a bad thing in some ways.

What’s really kind of disturbing to realize is that none of that is really intended or planned, either–It’s just kind of the way it works out, with how we run the Guard. You’re not gonna find an articulated plan anywhere that made that cohesion and identity come about–It just grew. Despite the institution and its policies…

Which is precisely why this uniform thing ain’t gonna have the wonderful effect everyone is hoping for.

I just recognized something you wrote here as being significant:

“We knew the history of the unit and prided ourselves on carrying the torch in our unit’s specialty. To the point where I switched services and STILL consider our company insignia, official and adopted, to be a point of pride in my office. Where even though the AD/ARNG partnership has replaced their SSI, the old unit SSI is a known and reverenced piece of the heritage.“

That bit about the SSI? That’s why this uniform thing won’t effect squat for change or fixing things; the key issue here isn’t the symbols, but the relationships, the brotherhood they represent. With a Guard unit, you can change the role, the mission, the guidon, and everything else, but… The people remain the same, and the interpersonal relationships, loyalties, and knowledge that are essential to cohesion and identity are still there, unaffected.

It’s the people, stupid. The PEOPLE. Everything else is dross, and unimportant. The uniform, the equipment, the mission–Change those all you like, and so long as the essential brotherhood remains intact, you’ve got a solid military community–A unit. Keep ripping those communities apart and continue to base them on constantly shifting sand, and they will never get past the point of casual indifference on the part of their members.

Try to reverse-engineer the whole thing by handing out spiffy clothes that don’t have a connection to those things that actually bond the community? All you’re doing is rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, as the water rises around your feet.

Kirk, do you see value in keeping people within narrower communities? IE: Keeping individuals within CO, BN, and BDE for longer periods in their career and move upwards within those closer organizations? Similar to the above observation on ARNG units?

If you want my honest opinion on the matter, I think we ought to start by just stopping everything we are doing that contributes to chaos and turbulence in the ranks. Instead of evaluating every goddamn personnel assignment decision based on what is good for an individuals career, we ought to bias everything towards what is good for the unit, instead. Change command in a combat zone because LTC X needs an assignment, and LTC Y has completed his tenure? Madness. Command ought to run from pre-deployment through the end of a full-on recovery phase–And, screw “career progression”.

Kirk,

Perhaps you could share some of your experience. Perhaps without giving away too much if you want to maintain relative anonymity, but it would be good for everyone to understand where you are coming from.

Hmmm. Experience? Watching them swap out our brigade commander midway through OIF I. Both of them were great guys I liked working for, but… Continuity? And, what that swap says to the troops? “Oh, yeah… BTW, the commander is going to another job that’s more important than you and your welfare, so suck it up, buttercup… His career is more important than you and the unit…”.

The other issues are ones I’ve seen down at the platoon/company level, where we were switching out key leaders almost as soon as boots hit the ground upon redeployment. This is an issue that kept cropping up, because what would happen is that there’d be “that guy”, the one who was the rock on deployment number one, who always volunteered to be out doing the difficult missions, and taking the brunt of it all. Swap out his key leaders, or send him to another unit nearly immediately, and “that guy” is suddenly among strangers who don’t know what he did or how much stress he was under–So, they let him go to the head of the line and keep beating his head on a wall during the next deployment, because he had already “been there, done that…”, and it just seemed like a good idea to use him for those really tough route-clearance missions.

After all, he was the expert with the most experience, yes?

Only thing was, the cumulative pressure and continual exposure to blast overpressure caused TBI, and after his second tour, his performance dropped. By his third, including (if I remember rightly…) about his sixth command team, he was slipping. And, because there was no continuity of supervision, let alone leadership, they kept letting him go to the head of the line and be first out of the wire.

By the fourth deployment, he was a wreck, and completely unrecognizable as the bright young junior enlisted guy I’d sent to the E-5 Board back around the end of the ’90s. And, I specifically blame that constant turbulence in his leadership–Nobody had the continuity to see that he was being broken, and I only saw occasional snapshots of him, since they’d PCS’d his ass immediately upon our return from OIF I. I kept in touch with him periodically, and I’m telling you, that lack of continuity was what did it–They kept using him, and eventually used him up. By the time I last saw him before I retired, he was done, an utter wreck. If I remember right, due to issues relating to the behavior changes stemming from TBI, he was given a less-than-honorable discharge, which I thought was a crime. He’d had something like 16-plus documented TBI incidents when they went to count it all up, and God knows how many that didn’t get reported or documented. And, the hell of it was, no one leader knew of more than a few in any of his multiple units. He had been on four full deployments, and in four different units, with I don’t know how many chains of command. The company commander he’d had in 2003-04 got wind of him being discharged, and went ballistic on the guy who had the misfortune to be his last company commander before discharge, and what they found when they compared notes was utterly devastating to how we manage troops. Due to the lack of continuity, and the constant turbulence in his units, nobody had caught what was going on with him, and they basically let him put himself out there and self-destruct. I can’t blame the individual commanders, because they didn’t know what he’d done on his last assignment, or what he’d been like before it all took effect, but… Jeez, what a condemnation of how we do business with the troops.

And, if you think there weren’t guys like me watching that, unable to really do anything about the whole travesty, and who weren’t profoundly angry at the sheer wanton waste and destruction of what was a superlative soldier? You’d be wrong.

And, most of that crap happening is due to commanders going in and out of command like so many kids playing musical chairs. New guy coming into the unit after redeployment? He knows nothing of what those troops did on that deployment, and naturally takes the attitude of “Well, what have you done lately…?”. He sees a guy struggling with alcohol issues, and doesn’t know that that staff sergeant spent a day and half pulling burned husks of troops out of the vehicle ahead of him that hit an IED, some of whom were initially still alive, or that he was supposed to be on that vehicle… All that new guy knows is that there’s this staff sergeant promotable who’s got issues with alcohol and being late. He doesn’t know what he was like before that day in the desert, and he usually really doesn’t care–Because our system doesn’t want him to, nor does it think he should.

And, shit like that is why we have problems with cohesion and why the troops don’t identify with the unit or the Army. They see an organization that’s impersonal, and that demonstrably doesn’t effectively care about the people that make it up. All it takes is one new commander who doesn’t know the individual issues of his new unit, and bang, zoom… There goes years of carefully built commitment to the unit and the Army. What really sucks, though, is that the poor bastard really isn’t to blame–It’s just how we do business, and how we train these guys. Nobody has the mission of looking out for the unit’s corporate interests, or the interests of the individual unit members, so… Shit happens. And, when it happens to guys you know, that breaks the bonds of institutional loyalty, as well as those bonds you’ve got with your leaders.

I’ll never forget reaching out to a commander we shared, looking for help with a guy who’d broken his back to make that young captain look good, and who now needed a character reference. The look of utter bewilderment he had when I asked for his help told me it was a waste of time, and so it proved to be.

You reward men like that with promotion, and success? Guess what? You get precisely the behavior you reward from everyone else. The commander is swapped out, for “career progression”, and what does that tell PFC Smith about the Army’s priorities? It sure as hell isn’t the unit; it’s everyone else’s personal interests, with the most benefit going to the higher rank.

Just what the hell does the Army think the mandated award policies do, in the long run? “All Sergeant First Class and above will get a Bronze Star, and no junior enlisted will receive anything higher than an AAM or Certificate of Achievement”. WTF? Y’all want PFC Smith to invest his loyalty and love in an organization that does things like that? And, you’re surprised when he declines the opportunity to re-enlist, thinking of how Staff Sergeant Roberts got ground into hamburger in Iraq, only to return to the US and get PCS’d over to a unit leaving for Afghanistan in three months? To fill “critical personnel shortages”? Some of which were caused filling the very unit that just returned?

Fix the madness that is our personnel system, and a lot of things we see as broken will fix themselves.

Kirk,

Thanks for sharing that. I have to admit that I never personally experienced what you are describing. In SF Groups (and SOF units in general) it is essentially the same folks rotation after rotation. Even most of our support guys stay in Group for many years and multiple rotations.

Because of that we can maintain better visibility and keep track of the sorts of injures or accumulative deployment pressures you are talking about. The OPTEMPO is high, but that kind of unit stability helps immensely. Of course that is exactly what we have been talking about that is missing from many conventional units today.

TLB

SOCOM and the other elites have much less of the BS we’ve allowed to take over in the rest of the Army. What’s good about that is that there is something to point at and say “Let’s do it like that…”, and what’s bad is that a lot of the guys over in SOCOM are highly influential, and they’ve got no real idea about what’s going on out in the line units. Their lives are not ours, and vice-versa.

Looking at what I’ve written above, I may have “anonymized” a bit too much, and included stuff I heard about happening after I retired. The gist of it all is accurate, though–We really did break a guy exactly like that, and it was a team effort on the part of a bunch of different company commanders.

I think that there ought to be continuity of command from pre-deployment through to well past re-deployment, and that we ought to be taking a leaf out of the Canadian Army’s books, and doing a mandated unit-level stopover somewhere like they do in Cyprus, in order for the troops to decompress and re-acquaint themselves with what it’s like to “not be in Holland” anymore.

For anyone missing that reference, that’s a common saying from the time of the Spanish wars in the Netherlands, where the rules of daily life for Spanish soldiers were not quite what they were in Spain. Upon return, the custom was for a misbehaving Spaniard to be called out by his friends, by them saying “Are we here, or are we in the Netherlands…?”.

There are a lot of things we should be doing differently, but the first place I’d start would be in reducing turbulence out in the units. The idea that we need to have this huge cadre of half-assedly experienced officers to rapidly beef up to a mass-conscript army? That necessity died out in the late 1970s, but we’re still doing manning, command selection, and personnel management as though that were a critical goal. I’m not sure that it was ever a good idea, given the syndromes it gave rise to in Korea and Vietnam–Punching a ticket should not be a reason to be in command, and the criteria should be simple: What is best for the unit?

That’s probably the biggest thing we’re screwing up: The entire ethos and mentality of how we do things. Everyone is concerned for their oh-so-important and sacred career, and nobody cares about the unit. Commanders see their time in command as being the point of it all; the Army has seen fit to lend them a company in order for them to look good and do great things–Or, so they are encouraged to believe in all too many cases.

The reality is that the needs of the unit must come first and foremost, because no matter what, none of us are more important than that entity, because that’s the key element to victory in war. One great soldier doesn’t accomplish anything by himself, but a dozen mediocre ones led well, and with good cohesion and team work? They can win battles together.

And, that’s what we’ve lost sight of, and need to get back to.

Kirk,

Well said and spot on. If you haven’t already read MG (RET) Aubrey “Red” Newman’s articles that used to be the mainstay of Army Magazine I recommend them. IIRC, he was a rifle company commander for nine years – yes, nine years – in the 1930s.

His articles were collected in several books back in the eighties titled “Follow Me!” and are no doubt out of print but may be available on ebay or elsewhere on line. He focused on leadership and teambuilding, but his work also gives insight into how personnel management was done in the old Army. Hint, almost none of it was centrally managed.

TLB

Somewhere, I’ve got a bunch of his stuff collected, and most of his books. Great stuff, and it gives you a lot of insight into what changed from “back when”, when we were a much smaller army and didn’t do everything on a production-line basis.

I think we’d do well to utterly abandon most of the massive bureaucracy that we built to fight WWII with. Go back to the way it was done pre-WWII, and have the units run their own basic training, with their own people, and put company commanders back into real command for the entire process of creating soldiers. We have forgotten the full spectrum of what the job is, having broken it down into production-line tasks for creating mass conscript armies. With modern distributed organization, I think it would be possible to maintain standards, and decentralize training back out to the units, which would have the effect of improving a lot of things–If you’re the guy who’s gonna be the squad leader of the knuckleheads you’re training to be soldiers, you’re not gonna pass on trash that can’t pass a PT test or that has demonstrated disciplinary problems. As well, decentralization puts the commanders out there back in charge of everything they should be, from initial entry training to mission performance.

We didn’t used to do things the way we do now, and there’s nothing saying we have to keep doing them this way. The massive bureaucracy and institutional training base makes no damn sense for a modern army not based on mass conscription, and I don’t think we’re going to be fighting a mass conscript war again for a good long time–Professionalization is here with us to stay, for at least as long as it stuck around before Napoleon. Power down, and distribute all that crap, I say…

“Approximately 75% of soldiers get out after one term or less, 50% of officers leave after completing their initial obligation.”

It’s not the uniform causing that, although the UCP I wore my last few months certainly reinforced the decision to leave after surviving 5.

Big Army has big ideas that are terrible in execution; poor leadership/mentorship and lack of esprit de corps kills retention.

I wonder how it is in the Coast Guard…

What you’re saying goes to the core of the issue, although the retention rates may simply signal a bump in the turnover rate reflected by modern culture–“Jobs for life” ain’t really a thing, these days, and the Army is naturally going to reflect that.

There’s another set of numbers that they don’t, and probably cannot or will not even try to, and that’s the set of numbers that reflect the amount of identification soldiers have with their service. With Marines, they’re like vegans or crossfitters; that’s like the first or second thing they’ll tell you about themselves. With the Army, a lot of the time? It’s “Oh, yeah… I was in the Army for a coupla’ years…”, and that’s something you hear to your surprise after knowing the guy for ten-fifteen years.

The idea that we start fixing this by addressing the ephemerals first is madness. You want to fix the Army’s issues with this set of issues, then the first thing you need to do is acknowledge the fact that the Army needs to stop treating soldiers like so many widgets coming out of a factory somewhere, and begin actually building unit cohesion in an effective and consistent way. Slapping a band-aid made of CARS or COHORT on top of the sucking chest wound that is our personnel management system won’t do it, nor will any new uniform. Fix the way we think of our people, how we treat them, and everything else will follow naturally, including pride in uniform and appearances.

I feel like the stereotypical cop in a slasher movie; the teenage girl has called me, describing the obscene phone calls she’s been getting, and I’m tracing the line to find out where they are coming from… She’s calling, calling, and I’m trying to convince her that the calls are coming from inside the house…

The Army is that teenage girl, frightened out of her wits because of the issues we’re having with retention rates and all the rest. The difficulty is, she won’t accept that the calls are coming from within her own house, and that she needs to deal with that fact before anything else. We’ve got the problems we have with this arena because of the things we’re doing, and until we address those foundational causes, changing the uniform is going to fix nothing.

Joe,

Of course, I was not implying that uniforms were having any direct influence on retention. The factors Kirk and you are talking about are much more significant in influencing soldiers to stay or go.

Those numbers are approximately the normal attrition rates for the Army. As far as I know, the other services are not much different. The vast majority of people, officer and enlisted, serve just one term and go on to other phases of their lives.

The fact is that is generally a good thing. We need fewer sergeants than privates and fewer captains than lieutenants. The services – and the Army specifically – struggle with mixed results to retain the most talented. Keeping quality people is much more important then just retaining a certain quantity of people.

TLB

Kirk,

Thank you for taking the time to weigh in. I appreciate your perspective and your passion about all of this. I totally agree with you that team building, unit cohesion and bonding have been damaged and not helped by decades of deliberate Army unit and personnel management policies.

I just found out a couple of months ago that the newest unit in the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) is the 1st Bn, 26th Infantry, Blue Spaders. A unit with a long and storied history associated entirely with the 1st Infantry Division. I got to chat with some of the kids in the outfit and this is no ding on them, but I could not help but wonder who thought this was a good idea?

That is a rhetorical question. I know the answer. For decades the Army has been racking and stacking unit linages and has made countless decisions to save as many unit flags as possible regardless of all the negative consequences you so rightly point out.

I agree that needs to stop. I also agree that a new uniform will not change that dysfunctional dynamic. However, I submit that a new uniform will not make it worse either. And, as I have argued, I do think it is a positive first step. Thanks again for reengaging in the discussion.

TLB

Yeah, that’s nuts. It’s like the people making these decisions have zero familiarity with the whole idea of what a unit identity is supposed to be, or how they work.

As I said, I don’t know why they even bother. They might just as well shut the whole thing down, and go to anonymous gray outfits with numbered units that have no expectation of maintaining any kind of identity, because that’s the practical effect of how they’re managing all this stuff.

What good is CARS, for example? Does anyone even identify with their “regiment”, at all? So far as I can see, we’ve turned it into just another piece of bling to stick on the dress uniform, and that’s it. The whole concept was flawed from the beginning, in my opinion, and all it’s played out as is another expense when it comes time to do a dress uniform inspection.

I don’t think that the people behind all this have one damn clue about what makes these things work, out in the real world. For them, it’s just career-enhancing movement of pieces on a game board, and the “unit identities” they are thinking they’re enhancing don’t actually exist the way they conceive them. You don’t just stick units up on a board, randomly associating them like some kind of demented quilter, and expect anyone to identify or care about them.

You could probably randomize the divisional unit associations, to some degree, but the key and essential thing is the anomie and disconnection we create with our personnel management system that goes hand-in-glove with this moving around of unit flags. The way we do it all, they might just as well throw the whole system out, and start doing unit designations using random alphanumeric codes they generate like so many CEOI instructions…

Kirk,

In that example, the Blue Spaders are now part of the Strike Brigade along with two battalions of the 502nd. I am guessing since it was the 1st Bn, 26th that there are no Spaders left in the 1st ID? That cannot be right.

Ironically, the individual regimental affiliation business works pretty well for ARSOF units like Special Forces and the Ranger Regiment. However, that is related more to the coherent nature of those units rather than any intent by the Army.

Good discussion. TLB

Excellent Kirk! You get it.

What I’ve got is chronic hypertension from giving a fuck about my Army, and watching the inept and delusional way it’s been run, and looks to be continuing to be run, on into the future…

Abstractly, I honestly kinda like the P&G uniform, and if it were in a vacuum, I’d probably like the idea. The problem I have with it is the expense, the recent change to the ASU just having been completed, and the fact that the idiots behind it all really think that it’s gonna address the issues they’re saying it will, in terms of that “brand and identity” thing. It’s not going to fix an ‘effing thing in that regard, because the problems they rightly perceive as existing aren’t sourced in the costumes we dress the troops in, it’s how the hell we’re running things on a daily basis.

Vacuum state, with no other impingements? It’s a decent uniform. I’ve got some issues with the practicality of the taupe slacks, but it looks good on the right model, with proper tailoring. What it’s gonna look like on general issue, in massed formations moving across grassy fields, and with guys serving as ushers at ceremonies, and actually, y’know, doing stuff? I have my doubts.

The P&G uniform was worn by officers, who aren’t exactly noted for doing more than stand around in their dress uniforms and look good. That was the point–The worker bees who were out marching in close formation and actually doing stuff…? They weren’t wearing taupe pants, and for good reason.

Ah, well–This looks to be a done deal, and even though I suspect we’ll be back in here in a few years decrying the foolishness of this decision, I can’t do much about it.

Kirk,

And then you had to put in a little dig about officers. I’ll have you know that standing around and looking GOOD while doing it is not as easy as it might seem.

TLB

It’s not a dig; that’s y’all’s job. If you’re getting your hands dirty, then the shit has hit the fan, and the rest of us haven’t done our jobs.

In any ceremony or unit function, the officers are supposed to look good–It’s the rest of us who’re supposed to be doing the dirty work, getting muddy and waiting the tables, so to speak. That’s the role you guys play, and even though we’ve kinda ignored that in our Army, for years, that’s what you guys do, especially working with folks like the Koreans.

What we dress our officers in shouldn’t include the expectation that they’re going to be doing physical labor in those uniforms, although that happens. The P&Gs are going to be nightmares for those times you guys are doing stuff, like being on the serving line at Christmas in dress uniform. Honestly, I think you guys can kinda start planning to write off a pair of slacks once a year, from that alone. The one thing people who wore those things have mentioned consistently was the ease with which they stained. Maybe fabric technology has improved, but I’m still seeing gravy stains rendering ’em unserviceable. When I did serving line duty, in the Class “A” uniform, that really didn’t show up after they were dry-cleaned.

Again… Not a dig, just an observation of fact. You commissioned folk are supposed to look good, and set the example. As such, a sharp-looking and impractical uniform ain’t really an issue–Which it is for us hewers of wood and carriers of water.

Kirk,

I stand corrected. Good point about the roles of officers and NCOs being different. Traditionally, and in good units, the roles are mutually supportive and synergetic. I have it as something I want to discuss in a future article.

Finding the right balance – at the small unit level especially – is often particularly challenging. Specifically because the platoon level is where the most junior officers and most junior NCOs first learn how to interact effectively.

If you have ever read James McDonough’s book “Platoon Leader” he shares a relevant story. He takes over a platoon in Vietnam. The platoon is already routinely sending out squad ambush patrols almost every night.

McDonough has been taught that an officer does not ask his men to do anything he would not do. Therefore, he joins every patrol for a couple of nights thinking he is doing the right thing, sharing risks with the men, and setting the right example.

His NCOs saw it differently. While it was not his intent, they thought he was micromanaging because he did not trust them to do their jobs.

McDonough was properly chastised but explained his reasoning (which he should have done in the first place) and they all learned from the experience. From that point he only joined those ambushes occasionally as was more appropriate.

TLB

I’m guilty of sometimes tarring the entire commissioned side of the house with the brush I should really only be using on certain specific elements in it, and I really shouldn’t do it. For that, I apologize.