Lately there has been quite a bit of talk about the connection between history, professional military education and quality training on this site. Perhaps we can all initially agree on a couple of facts to frame some additional discussion. First, war is a bloody art form much more than it is a science and requires continuous study and practice to truly master even at the tactical level. Second, planning, managing and conducting good training is also an art – and in many ways is just as hard to master. For the sake of brevity, I am going to address training separately in part two of this article so that we can concentrate on history as a component of professional education up front.

So how can studying history help make you a better soldier and build stronger units? To be sure there is an important caveat; any “lessons” gleaned from history cannot and will not give definitive answers to today’s military questions. The past is not some accurate predictive tool that can somehow be used to prophesize future outcomes. Nevertheless, the study of history certainly often provides valuable context that can and does serve to inform decision makers in the present. Therefore, it is safe to say that seeking to understand events and characters in history does indeed teach and enlighten.

Obviously countless others have had a similar opinion about the enormous utility of historical study. I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that a great many notable historical figures have been self-acknowledged students of history. That has certainly been true of military leaders. Roman generals like Caesar studied the writings of the ancient Greek warriors intently. Not just to learn how they fought, but also how they successfully trained, motivated and sustained those earlier formidable armies. Later others studied Caesar’s campaigns to capture his insight into war. Each generation in turn contributing and perpetuating an unbroken military historiographic circle of life.

We now live in a golden age of information. I have more educationally sound books about all aspects of warfare throughout history sitting on the shelves in my home than were ever available to any general in WWII. Moreover, my collection is extremely modest compared to the exponentially greater volume of material accessible through any modern digitally empowered library. It would be a shame – really a crime – if those of us with that kind of fingertip access to vast reservoirs of information did not take full advantage of all of that educational abundance.

Based on my own personal experiences, I have always been able to learn a great deal about my profession from men and women who died long ago. Military philosophers and theorists like Clausewitz still speak to me. Over time I internalized his concepts, Sun Tzu’s teachings and Machiavelli’s advice and was no doubt the better soldier, trainer and leader for having done so. For me, reading “Lee’s Lieutenant’s” and “This Kind of War” or “The Uncertain Trumpet” was never some academic exercise that was not destined to serve any practical purpose. I learned to appreciate history from the example set by the leaders I met early in my career. In turn, I have tried to pass on that historical sensibility to those I have had the privilege to serve with, lead, and mentor over the years.

In fact, studying books like those above was vital to my vocational education and eventually critical to whatever success or failure I might achieve while practicing my profession. Most importantly, I was able to make better and timelier decisions in ambiguous and challenging circumstances than I would have if I had not had that reasonably broad and sufficiently deep historical exposure beforehand. I simply would not have full confidence in any senior military leader who had no informed sense of history.

To be clear, I am not talking about a formal educational or degree producing program. No one needs to run off and get a PhD in Military History in order to be a good soldier or capable leader. Indeed, we can start at the small unit level with resources we already have readily available. How many leaders out there have made the effort to teach their subordinates their unit’s unique history – let alone the Army’s service history? I can tell you that the answer is not enough. What campaign streamers do you display on your colors? What battles do the elements of your unit crest represent? Why is your unit called the Manchus or Cotton Balers or Devils in Baggy Pants. Of course you might ask, is that “minutiae” really truly important to know? How will that information help “kill the enemy” or keep my people alive?

The answer is simple and ancient in origin. Expending the energy to inculcate a unit’s history helps build stronger teams. The Roman Legions understood this dynamic. Even today, the USMC – better than any of the other services – still understands and leverages this important bonding practice. So why doesn’t the Army do the same? Some units certainly do, but far too many do not even try. Some units consider it a waste of time and a distractor from other priorities. I would argue that the leaders of those units have the wrong priorities. They are shortchanging the professional development of their soldiers and failing in arguable their most important duty. That is to build motivated, cohesive, and ultimately winning teams.

And no, this does not mean a unit has to “stand down” or curtail other training to get it done. Some still serving NCOs or former NCOs out there probably think I am trying to put another rock in your already-too-full professional rucksack. The fact is that particular rock has always been your responsibility. You are the keepers of a unit’s history, and by extension the Army’s history, and have always had the responsibility to pass on that knowledge to your soldiers. The majority of NCOs do not need a reminder. They know they have the mission and do a superb job. But far too many do not – probably because they were never taught what right looks like when they were growing up. You cannot set the example or effectively teach what you don’t know or don’t value.

Obviously, we need to work diligently on correctly that problem at the unit level. However, we should not stop there. What are some of the positive aspects of studying history for broader professional development? Below I have selected three relevant quotes from my favorite fiction book, “Starship Troopers” by Robert Heinlein. For those not familiar with the work, be advised that the book has absolutely nothing to do with the movie series of the same name except the title. I have literally read the book a hundred times or more and always carried a paperback copy with me on deployments. I also loaned it out many times. But it was not the plot or the characters that keeps drawing me back. Rather it was the core ideas; the embedded concept of civil responsibility and duty as well as selfless service and even insight into conflict and war itself.

As many of you know, Heinlein was a brilliant, unique and even odd historical figure. He wrote science fiction primarily and never saw combat himself. Yet in Starship Troopers, Heinlein was able to capture the quintessential rationale of voluntary military service and martial virtue. He clearly intended to present more of a philosophy of duty than a practical military theory or strategic concept of war. Still, his book is a recognized military classic and has been on the recommended reading list for the Army and the USMC for many years. That is not to say that all of Heinlein’s ideas were original. He was well read and had an inquisitive mind so I suspect he had read at least potions of Clausewitz and Sun Tzu and quite possibly Machiavelli as well.

I appreciate this first quote because it perhaps explains why Sun Tzu still resonates after more than two thousand years. Why Clausewitz and Jomini are still read intently to be both interpreted and misinterpreted by countless professional soldiers. And perhaps it also explains why no more contemporary authors have ever been able to convincingly threaten their intellectual authority or supplant them.

“Basic truths cannot change and once a man of insight expresses one of them it is never necessary, no matter how much the world changes, to reformulate them. This is immutable; true everywhere, throughout all time, for all men and all nations.”

The second quote might appear to be no more than a restatement of Clausewitz’s basic theory. And I am reasonably sure that was Heinlein’s original source. But it does expand on the idea that in war it is the application of coercive violence and not killing itself that is actually the military “means” to the political “end” or “objective” that Clausewitz referred to repeatedly.

“War is not violence and killing, pure and simple; war is controlled violence, for a purpose. The purpose of war is to support your government’s decisions by force. The purpose is never to kill the enemy just to be killing him . . . but to make him do what you want him to do. Not killing . . . but controlled and purposeful violence.”

Lastly, I have used what I call “the cooking analogy” below many times to try to explain the notion of military education and realistic training providing immense value added on and off the battlefield.

“…unskillful work can easily subtract value; an untalented cook can turn wholesome dough and fresh green apples, valuable already, into an inedible mess, value zero. Conversely, a great chef can fashion of those same materials a confection of greater value than a commonplace apple tart, with no more effort than an ordinary cook uses to prepare an ordinary sweet.”

Unfortunately, higher-level professional training and education is largely undervalued in the institutional military. That is a counterproductive but systemic organizational attitude. To use Heinlein’s analogy, the services consequently only manage to consistently produce good “fry cooks” that can perhaps reliably fashion an edible meal but have a limited repertoire. In other words they are generally “tactically sound” in the most limited sense but not necessarily adaptive, multifunctional or innovative in any way.

We simply do not produce many world-class chefs; i.e. master craftsmen or artists with more advanced skills that can take the raw material and other means provided to them and produce results approaching a tactical, operational or even strategic work of art. We need military artisans who can be hard fighters AND consummate trainers AND equally deep thinkers. Leaders that have the intellectual tools necessary to profoundly reflect on the art and artifices of war and the disciplined aptitude to translate the resulting thoughts into practical applications. The enduring challenge for us remains how to identify, cultivate and encourage the intellectual development of more martial master chefs at every level.

That brings us to the final point for now. It would certainly be possible to put a committee together and “distill” the more advanced works of Sun Tzu, Clausewitz, et al into 3×5 cards of command approved military axioms that every soldier could carry in his or her breast pocket. Laminated of course and dutifully memorized and regurgitated on command. But that will not make us any smarter. To seek legitimate understanding of Sun Tzu and the others it is important to consider the social, cultural and historical context in which they lived and wrote. In other words, it takes intellectual effort. There is no shortcut.

If simply taken literally, out of context, or only partially and imperfectly understood, Sun Tzu’s or Clausewitz’s or Machiavelli’s ideas can be truly dangerous rather than helpful to a soldier or politician trying to make a decision with life and death implications. Therefore, the services – especially the Army – would clearly be best served by providing more opportunities for high quality, practical and continuous professional education at all levels. This could start by making the effort to instill a deeper appreciation of history in Army leaders of all grades. That is probably the single most useful thing we can do to improve the U.S. Military’s tactical, operational and strategic rate of success in the future.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

Tags: LTC Terry Baldwin

The uses and utility of military history go a lot further than all too many of us think. It is not just the great sages like Clausewitz, Jomini, and Sun Tzu whose lessons that we need to study, but the little things like “Hey, two commander’s ago, we tried doing things just the way the new guy wants to do them… How’d that work out?”.

Military history isn’t just dry, dusty tomes of ancient sagacity and wit; it goes on around us on a dsily basis. Young officers and NCOs are encouraged to work their way through volumes of approved lore, but they would better served to study more recent and pertinent things, like organizational AARs and histories (which generally need major improvements). The creation, formalization, and promulgation of institutional memory is something we do badly, overall. That needs to change, if we are going to be able to identify and fix a lot of our problems. Ignoring history the way we often do is a pattern of behavior that stems from some deep roots in our institutional cultures, and while it sometimes serves us well to look at problems and situations with fresh, unprejudiced eyes, it more often results in us re-inventing the wheel in a continuous and entirely wasteful manner.

“…the little things like “Hey, two commander’s ago, we tried doing things just the way the new guy wants to do them… How’d that work out?”.”

YES. This. One hundred thousand percent this!

That said, this is really a separate and not entirely related point having to do with institutional memory. TB’s point that people with a deeper breadth of knowledge tend to better handle situations they have no specific training for or direct experience with is equally valid.

Pete, I have to disagree with you. In my opinion, much of our problem with effectively inculcating and teaching military history at the “big picture” level actually starts down in the weeds, at the micro-level we term “institutional memory”.

I knew a lot of guys who read all the books on the reading lists, and were left with absolutely nothing to take away to daily life. Why? Because, they’d lost the connection between the words of wisdom they’d absorbed, and saw them as abstractions, things useless in daily life. And, by-and-large, they were. To them.

You want to use a tool, like military history, you have to have a mindset conducive to that, and be able to discern the benefit to you in daily life. Read Jomini, and then try to look around your average infantry unit, and look for the application of what you just read in daily life. It ain’t there on the surface, easily visible.

You want to fix the higher issues of our poor use of military history, you need to address the problems down at the lowest level. Institutional memory isn’t working when the only guy in the unit that remembers how things went pear-shaped the last time this bright idea of the new commander was tried is the superannuated E-6 riding out his term to retirement in the Ammo NCO slot. He’s unlikely to be listened to by anyone but his peers, and the only real benefit to the whole thing is a bunch of mid-grade and senior NCOs get to stand around at coffee breaks nodding their heads wisely and going “Told ya so…”.

You want working institutional memory, you need an officer corps that understands, respects it, and does its best to actually create and maintain such a thing. The vague premonitions you hear mumbled in the back ranks when a new policy is put out don’t do you a damn bit of good–What should have happened is that the new policy or procedure should have been run past the “keepers of the flame”, and then thought about. If you don’t have anyone bothering to spark that flame, keep it going, and then respect it? Well, guess what? It’s just more useless verbiage thrown out there that sounds good.

I think a major part of the problem with our macro-level military history stuff starts down at this nanoscale, where we have no respect for what went before us at the lowest levels of operations. A young lieutenant who isn’t mindful of, or even aware of the lessons of his peers that preceded him in that position isn’t likely to grow into a battalion or brigade commander who will be able to read, process, and utilize historical lessons out of someone like Slim. You want to see successful use and respect for military history on the broad scale, you need to start out at the small level, and work up.

I think every junior officer and NCO ought to keep a daily journal “for the record”, and then use that to write up a short summary of their time in their position, which would be combined with those of their subordinates and seniors. Yeah, you’ll likely have some problems with maintaining fidelity to “what really went on”, but you’d be inculcating the uses and value of history to those you’d have read those journals and summaries before taking over that position. Like continuity books, but with the supporting “why we did that that way” included.

Start small, and the bigger picture stuff will fall into place. Right now, most junior officers and just about all the NCOs see the reading-list history as useless-in-daily-life abstractions. Make a connection to the here-and-now, and you’ll see a lot of improvement. Or, so I think.

Kirk,

I agree with what you are saying. People tend to appreciate and value only what they perceive to be useful right now. Currently a lot of people do not see history as useful. Even recent practical unit history like you are talking about. It just becomes more information that is written down but never read.

Yes, some have to be pushed, but I have seen many see the light after being introduced to some palatable “gateway drug” like Starship Troopers or Killer Angels or Gates of Fire. Leaders sometimes need to do a little more pushing.

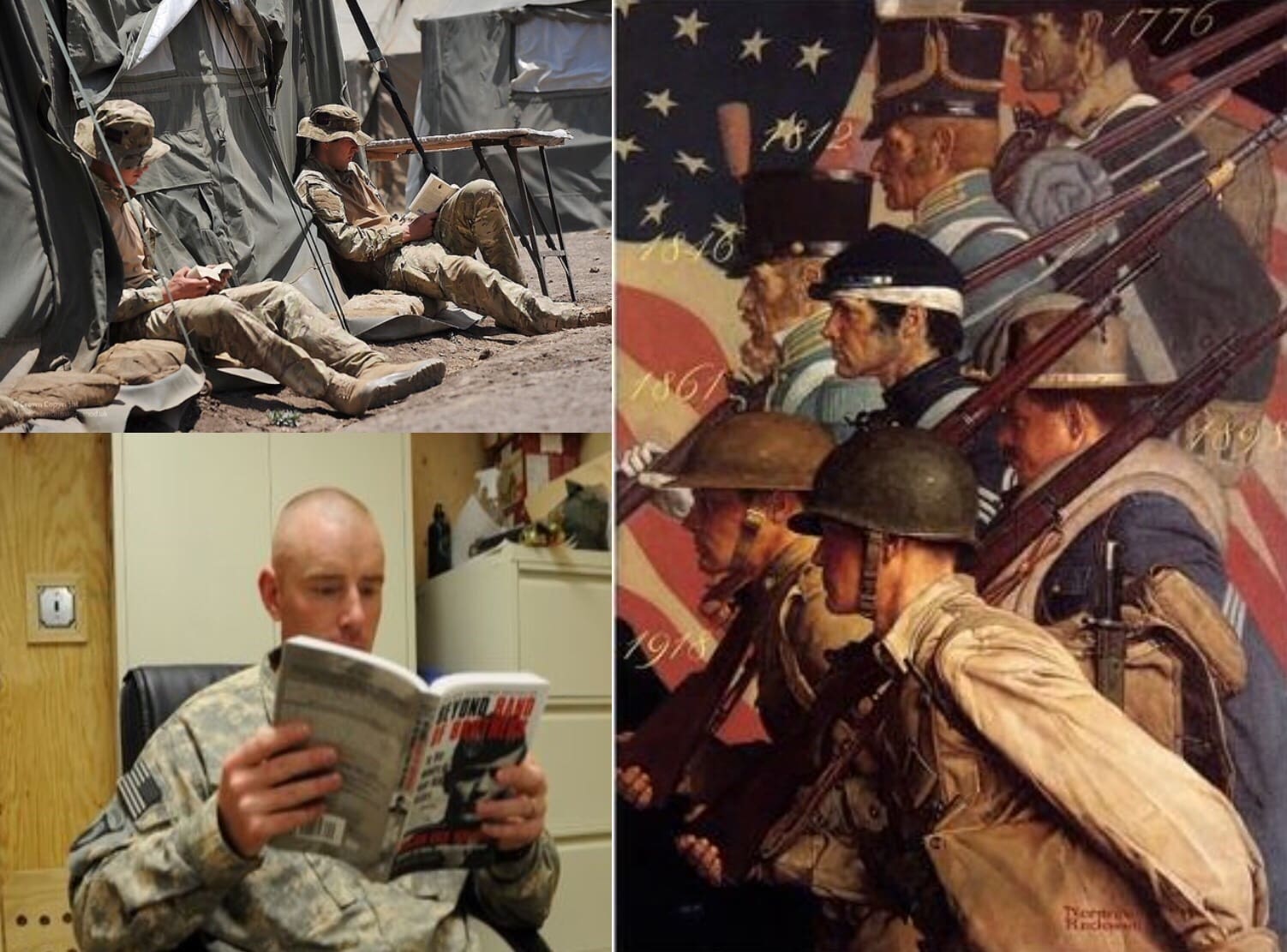

One of the reasons I have always liked the Norman Rockwell painting on the right above is that it shows the then current WWII soldier walking alongside his predecessors. He is not at the front of a line that never looks back. Those earlier heroes are alongside him as he moves forward.

If the soldier has been taught his unit and service history he knows that. He or she should understand that they are already a part of that history. At least that is one good place to start.

TLB

Agreed. I think I would go so far as to say that a lot of the essential process of inculcating and indoctrinating the average young soldier, enlisted and commissioned, is utterly broken. The incontrovertible fact is, the Army is horrible at teaching soldiers history, and that’s a huge component of what goes into developing unit cohesion, continuity, and pride.

We’ve gotten to the point where a young former enlisted Ranger converted to outright full-bore Communism, while attending West Point. If that doesn’t highlight the issue, I don’t know what the hell will. That should not have happened, and would not, were we doing a good job on acculturating and conditioning young soldiers. That a former member of an elite unit would be vulnerable to such persuasion and at a service academy…? Yeah; we have a problem.

And, much of that problem boils down to the fact that we don’t talk about this “stuff” in the Army. Just like we don’t talk about killing, we don’t talk about the political and historical facts of life, and that leads to a bunch of side effects, this being one.

There’s a lot wrong with the Army culture, and it’s been wrong for a long time. I really only began to realize the magnitude of the issues once I was retired, and had time to reflect on the things I experienced and went through. We pay a lot of lip service to a lot of things, but when it comes to taking concrete measures…? We fail; everyone talks about institutional memory, but who the hell takes the time to institutionalize the memories of our experiences, and then actually makes use of them in a way that demonstrates it’s more than fulfilling a mandate? Who is out there recording things, and transmitting them? What commander has the humility to go around and ask long-term members of the unit “Hey, has anyone tried this…? How did it work? What were the problems with it…?”. Instead, we’re all a bunch of arrogant sods (I didn’t learn about Chesterton’s Fence until way too late in my career… Shoulda had that shit beaten into my head during PLDC, to be honest…) that think the world started with us. And, it didn’t–Nine times out of ten, the “new school” is just the school before last, and there are reasons the “old school” replaced it.

Kirk,

Thanks for bring up Chesterton and his fence. It is sage advice for any would be “reformer.”

As I understand it, that West Pointer you are talking about left 1/75 because of a “relief for standards.” In other words he was not up to the RR’s standards – but I do not know the specifics. Still, the question in my mind is if he could not meet Ranger standards, why then did he get an appointment to the Academy in the first place?

Late in his career, S.L.A. Marshall made the case that the Army needed to have dedicated people “sitting on the side of the trail” as he put it. Those people would observe, record and report what was going on as the Army went about its business. Part combat reporters and part historians. Which, not surprisingly, describes what S.L.A.M. had been doing much of his time in service.

We still have a few historians on the Army payroll. Good academic historians. They dutifully go out and gather information and put it in an archive somewhere. I’ve been interviewed myself a few times over the years and have facilitated others being interviewed or providing records for the sake of history.

What S.L.A.M. did that others haven’t done is synthesis and produce useful Cliff Notes from all that data like “The Soldiers Load and the Mobility of a Nation.” Unfortunately, what we have now is only of utility to some Historical PhD candidate researching his thesis and not for soldiers in the field.

TLB

This…

“What S.L.A.M. did that others haven’t done is synthesis and produce useful Cliff Notes from all that data like “The Soldiers Load and the Mobility of a Nation.”

We need cliff notes and rules of thumb that have been analyzed by our best and package for our youngest. Then taught and trained by our first line leaders. Unit turnover (personnel/deployments) is so fast it’s difficult to bring people up to speed without the nuggets of wisdom to bring our dry, two dimensional FM’s to life.

Warfighters working with professional historians are the mechanism for producing this kind of knowledge. I’m sure it’d be faster than a Critical Task Selection Board trying to implement changes to TRADOC lesson plans.

With the turnover we’re seeing in Army Aviation (my career field for the last 22 years) the amount of ” they don’t know what they don’t know” I see these days is approaching a dangerous level. A key way to combat this ignorance is a focused look at military history…. integrated into our training models. But don’t get me started on objective T.

Tom

All too much of S.L.A. Marshall’s work is suspect. The “data” behind his rate of fire and fire participation “studies” appear to be made up out of whole cloth.

Historian lies one place, where do you draw the line for believing any of his other work?

I think that Marshall was a glib fraud that took the Army for a ride, and the more I look at my collection of his works, the less credible I find it. Hackworth has some illuminating things to say, describing his experience as one of Marshall’s escorts during Vietnam, and I’ve heard similar stuff from the old-timers I talked to from WWII, a couple of whom claimed to have been participants in Marshall’s open-air sessions.

Kirk,

I agree. Marshall had his own self-serving agenda and the “data” that supports his work is often of questionable veracity.

As with everything else I read, I compare what Marshall writes to what I have experienced – or in some cases others have wrote – to crosscheck the validity and the utility of what he says.

I agree with you that he got it wrong perhaps more often than he got it right. Like you, I believe his rate of fire conclusion in particular is fatally flawed.

Even more so the associated theory that men are somehow naturally inhibited from killing. That subject is a particular sore spot for me because it was used as the justification for the junk science nonsense with the same theme that Dave Grossman started peddling in the mid-90s.

On the other hand, I do thing Marshall got in right in “Soldiers Load and the Mobility of a Nation.” Not because he says so, but because overloading soldiers unnecessarily is something I have witnessed throughout my career.

I also obviously think that there is merit to Marshall’s concept of having dedicated “chroniclers” capture this kind of information – not to be archived – but to be disseminated in some timely manner and in some useful format to the force.

TLB

Soldiers released from Regiment for not meeting their standards are not always bad soldiers. Yes, get in trouble with the law, suffer UCMJ or bring discredit to the Regiment will get you separated but some fail simply because they cannot meet or maintain the Regiment’s incredibly high standards e.g. falling out of runs with a 6 minute mile pace, not maintaining the regiment’s high marksmanship standards, failing or not attending Ranger school etc. Many times the reasons a Soldier is separated from the Regiment never makes it to his personnel file and many of these soldiers go on to be great soldiers in their conventional units.

Rapone is an extremely unique case and worth studying. (I understand he was dropped from Ranger School for insubordination and signed an LOM which used to be a career killer.) I look forward to hearing how the Academy failed (as well as the 10th ID) to address some pf his now obvious character flaws. I suspect our all consuming respect for PC has a role as well as some key USMA cadre/leadership being asleep at the wheel. I also would bet the respect shown a prior service soldier with a CIB and Ranger Regiment combat patch shielded Rapone from some deservedly intense attention he may have otherwise received.

I had not heard that Rapone had been released from Regiment. With that in his records, how the hell did he make it to West Point in the first place…

Something in all this smells really suspicious.

The person who should come under scrutiny is his company commander who wrote him the letter of recommendation.

For a regular army Soldier to be admitted, rather than the rigorous process that a civilian off the street must go through to receive a nomination, then later to receive an offer of admission, all a Soldier has to do is receive a letter of recommendation from his company commander. That constitutes his nomination. West Point is habitually unable to fill all of its slots reserved for regular army admissions to the Corps of Cadets, so it’s easier for a Soldier to make it in than a candidate from the civilian candidate pool. All Rapone would have had to do once arriving at his unit after being RFS’ed would be to sufficiently impress his chain of command over time to such an extent that they got his CO to write the letter of recommendation, then provided he meets admissions requirements academically, physically, and with demonstrated leadership (by that USMA would likely focus more on High School accomplishments than what he did in the Army, simply because that is what the admissions process is habituated to do), and he’s in. Source for this: I got in as an E4 11B through this route.

Regarding the social and academic environment at USMA for his communist views…in my experience, West Point in NO way fosters views like that, either academically or through officer mentorship or through peer interaction. From talking with YG16 LTs who are classmates of Rapone, he was an extremely intelligent, very contrary individual who seemed to love to argue with others and draw them into debates. Some of these LTs believe that the communism stuff was just him trying to be contrary and debate folks that he didn’t like for attention, or a rebellion against West Point’s relatively conservative culture. In any case, I think this is where USMA strayed, because there are documented incidents of him acting in a disrespectful manner with instructors, and nothing coming of it. See LTC Heffington’s internet postings on this topic. LTC Heffington was an instructor in the history department prior to his retirement. I had him personally as a Plebe, he always struck me as a man of integrity.

Your first point is why I think there ought to be longitudinal tracking of the decisions made by commanders in these cases. I guarantee you that the poor bastard stuck with Rapone as a 2LT is going to get absolutely hosed, while the guy that passed the buck and sent him to West Point ain’t going to see so much as an unkind word over his failure to do his duty to the Army and the enlisted troops saddled with Rapone.

As well, I understand that there’s a full-blown big-C Communist infiltrator on the staff at West Point, who was Rapone’s “mentor”. Someone really needs to explain that one to me, because I’m just a simple enlisted guy who spent most of his adult life during the Cold War, and the idea that we’d hire and then allow an avowed Communist to run free at West Point…? What. The. Ever-loving. Fuck…

“Still, the question in my mind is if he could not meet Ranger standards, why then did he get an appointment to the Academy in the first place?”

I submitted a USAMAPS application in 1990 and was told by an Admissions Officer (who took the trouble to call me) that I would have received an appointment if it simply had been received earlier. He gave me a few tips for improving my chances and told me when the next application window BEGAN.

I was still in the age range and front-loaded an application for the next year. Then Desert Shield. Then Desert Storm. Then Provide Comfort. My BC sent the S-1 to Incirlik to ‘find a way’ to get my packet in (this was ’91–well before electronic submission). Same troop, more awards (earned in as much combat as DS allowed as well as the more challenging LIC environment that followed), letters of rec signed by field grades. Received within suspense but still too late.

That this guy got his slot indicates that the admissions process may not have changed much. Seat 80 “qualified” prior service applicants and close the books (probably to go back to normal duties–or better tee times)…

I had to laugh at the “cotton balers” name, considering that is what I build. Have to find humor in the small things.

Tazman,

Cotton Balers by GOD! That is the last line of a little ditty that celebrates having “two coats of hair, cast iron balls and a blue steel rod” if I remember correctly. I was never in the 7th Infantry Regiment myself but did serve in another infantry battalion that was near enough to 1/7 to hear that every time one of their PT formations ran by. The nickname refers to their service in New Orleans with Andrew Jackson at the end of the War of 1812. The American forces used cotton bales as breastworks against the advancing British.

TLB

LTC Baldwin. as always a well thought out and provocative essay.

I wholeheartedly agree with your position on the value of studying military history as a necessary tool to develop one’s own skills as a Soldier, leader and trainer.

Just to state the obvious though, sometimes one person cannot be two or all three. No matter what. I don’t believe one can be a great higher level (BN) leader or trainer without a sound grounding in history. Lower level leaders are also highly dependent on what kind of environment/resources/etc. those higher leaders create in their units.

One intangible that is rarely discussed or understood is the difficulty in creating, resourcing and maintaining good let alone great training in a large force. Every battalion has one great squad at any given time. The trick is replicating that across platoons, companies, battalions and brigades separated by geography and consisting of leaders of various qualities. Of course it gets impossible if the organization doesn’t value excellence in a certain type of training but many don’t fathom the enormity of the task to get an organization as large as the Army on one sheet of music..

I’m looking forward to more of your thoughts on the subject and while you didn’t mention it directly in the triad the study of military history is key to esprit and unit cohesion. Maybe you’ll expand to include your thoughts on those two areas? I think you’ll agree, sometimes part of the reason one wants to study history, participate in PME and be a superior trainer is because one has esprit, feels one is part of the unit, proud to be in that unit and dare I say it believes that “uniform” stands for something special.

Will,

All great points. Thank you for clarifying about a Regimental relief for standards above. I knew that and should have made it clear. I served with a number of truly sharp soldiers dropped from 2nd Batt specifically when I was in the 9th ID in the late 70s. Oddly enough, some that were already NCOs but who had no previous experience in conventional units did not always do well initially. They were not used to having to be as much of a disciplinarian as was required with some of the problem children in a straight leg outfit in those days. There was a tough learning curve.

True, some guys are going to be better at one rather than the other two. But I have never bought into the idea that there are garrison soldiers and field soldiers. If you are a professional you should be striving for excellent in two out of three at least. Fortunately, that is also why we train and fight as a team. The strengths of one can compensate for a relative weakness in another.

To be clear, I am not denigrating the guys (the majority) who only want to serve one term and get out. Although I do expect them to behave professionally, I know they will not have the time or inclination to put in the extra effort. That is perfectly honorable and I wish them luck in their future endeavors. Of course with the right mentoring some of them might change their minds. I did.

However, the kinds of people I concentrate on professionally developing are what I called in an earlier piece “[potential] long service Regulars.” Those are the guys who have demonstrated the drive to accept the challenge of mastering their craft over time. There are not many of those, but thankfully a few go a long way.

I met Hal Moore and some of the other veterans of LZ X-Ray back in the late 80s. Even before the book was written they were giving a professional development seminar on the battle to students at Ft Benning. That included NCOs at Infantry ANCOC and officers (promotable LTs and CPTs) at what was called the Infantry Officer Advanced Course in those days.

I will reference the movie since many of the people who frequent this site have seen it – and I just watched it again last night. Moore studied history before deploying. Not just military history but also the history of the region and the peoples. He wanted to be as smart as he could be even before he got there.

And he wanted his troops to be as smart and sharp as he could make them in the time available. He took his junior officers aside (as shown in the movie) so that they could get to know him and he could get to know them. So he would never be just some voice on the radio giving orders. Although it is only hinted at in the movie the SGM was doing the same with the NCOs. In other words the command team was focused on team building and unit cohesion. That is what smart leaders do.

Army wide the task is daunting as you rightly point out – and it is never ending. It always seems like when you do finally get to where you want to be there is a levy and you find yourself rebuilding constantly. That can be discouraging. Mastering a craft this complicated is hard and requires more than average commitment.

We do all need to have reasonable expectations and concentrate on what is appropriate at our individual level. People can move forward at their own pace. Still, for a PFC knowing a unit’s history may be a much as can be reasonably expected. But by the time he is going up for SGT he should know more. A Staff Sergeant and a Lieutenant should be working on mastering tactics. There will be time – and professional schooling – later to help guide them into operational art and expose them to strategic concepts. One step at a time.

Finally, each time I do one of these pieces I am frustrated by the fact that is always so much more to say. Volumes and volumes already written by smarter and more experienced soldiers than me. I can only hope to spark enough interest in the subjects so that people will go out and explore on their own. But I will try to do something in the future on those related subjects you mentioned.

TLB

Wholeheartedly agree there should not be field and garrison soldiers. (My second PSG came from DC’s Old Guard and was a great NCO in garrison but a downright divisive force in the field questioning why we did hard tactical things when easier administrative approaches would work. I digress…)

I don’t think I did a good job of saying what I meant. My point is some people while being great soldiers (in & out of the field) don’t make great leaders or great trainers. In fact it is the exception where one can do all three. Of course one should have a high level of competency in all three but it’s like your fry cook metaphor. In some situations a fry cook is just fine but I think where we want to go is developing a chef in charge of groups of fry cooks to improve our training and mentor fry cooks to become chefs. Some of those fry cooks will never make it by choice or lack of ability is what I was trying to say.

Unfortunately our system of promotion can exacerbate the problem. Some leaders are truly exceptional at their current duties but are then promoted to a position they can’t handle. I’m sure you’ve seen it and I don’t want to take the discussion into the weeds but this is part of the complexity I was referring to in trying to create Army wide training systems.

Will,

I understand your point. I agree that it is possible for someone to be a good trainer but not a good combat leader. It is easer to lead a training session on ambush patrols than it is to actually lead a successful ambush patrol in war. Combat is the final exam for any military leader – and some do fail that ultimate test.

But I do not think the opposite is possible. A good combat leader almost by definition has to first be a good trainer. He has to know himself and his men in order to be successful in combat. Training provides the only real vehicle to build mutual confidence before battle. Patton was obsessive about training as was Hal Moore, Matt Ridgway, Jim Gavin, etc. There may be an exception, but I cannot think of one.

Mentoring, if done right, is supposed to do exactly what you are describing in your second paragraph. Good leaders are supposed to prioritize aggressively developing those who have already shown potential.

Quality mentoring doesn’t happen as much as it should in real life because there is no system to link the already proven with the up and coming. It is left to chance. I have been lucky because I have had the great good fortune to work with and for some of the best over the years. Which was great for my professional development.

But most younger leaders are essentially stuck with whoever is in their immediate chain of command. They may luck out or they may end up with someone like the PSG you just described. One bad experience like that can discourage even the most motivated. Worse case it will convince them to leave.

This also touches on what you are talking about in your third paragraph and something I have mentioned before. That is the buzz-phrase “talent management” which is in vogue right now. It is a wonderful idea that I won’t dive too deep into right now.

But successful talent management is only a fantasy until someone shapes a real system to make it work. And that has vast implications over training, professional schooling, promotions and every other aspect of personnel management.

In other words you just about have to tear down the entire current system to build an entirely new structure. It does not appear like that will happen any time soon. So we will have to continue to do the best we can within the current system for the foreseeable future.

TLB

I’ve become convinced that the entire paradigm we use for organization is basically hopelessly flawed. Especially given the human material we’re going to have to work with, in a few years. Most of the kids are going to be geared towards the flexible “gig economy”, and entirely unwilling to lock in to these ossified structures that don’t offer them any room to influence things. And, if you think that’s not important, go look at our retention rates for young officers.

The structures are too big, too impersonal, and too inflexible. We bureaucratize and and ossify our units almost as a matter of course.

Someone really needs to go back and look at Robert Frederick, the Coastal Artilleryman who built the First Special Service Force. The way he did that, and the approaches he took…? I’ll be damned if know why we aren’t looking at some of his innovations for use in Afghanistant, like the use of a full-scale porter element that was damn near half the size of the outfit.

We need to take a more flexible, entrepreneurial approach to how we man and build units. A unit commander should not be able to treat the unit he takes over as some kind of personal serf kingdom, with the serfs tied to the unit. Guy can’t attract people who want to work for him? People want to get the hell away from him, to the point where they’d prefer to disrupt their careers? Gentlemen, that’s what we would call “a sign”, and be one we should be looking for.

Kirk,

I fully agree. We are at the true RMA point that everyone thought we had reached in the mid-to-late 90s with precision fires. It is people not technology that ultimately matter.

We are still using essentially 19th Century personnel management practices that are not going to serve us well in the 21st.

We had better master the challenge of modern talent management soon or I suspect we will pay a price in more blood in the not too distant future.

TLB

I did Ancient Greek (mainly the Peloponnesian Wars and Delian League period) and Ancient Roman history, specifically “Twelve Caesars”, Gracchi brothers to the reforms of Gaius Marius (and the problems it simultaneously solved and created, to the crossing of the Rubicon and death of the Republic) up to the zenith of Empire (Mediterranean being the ” Roman Sea”) in high school prior to my military career.

I’ve never been in a position of relative heavy responsibility but nothing could’ve educated myself better with issues regarding to democracy, republic, citizenry and its privileges, populism and leadership, and problems in the middle east repeating itself from 2000+ years ago until today.

Great piece as always Terry! I remember my early years in 2/505 PIR getting the Divisions history beat into me at every turn. I’ve have studied history, specifically military history of the two units I had the privilege to serve in with vigor. I have also been lucky enough to have to brief recent history I have been involved in via vignettes to most levels up to and including the Congress.

Thanks for taking the time to pen articles such as this; these are catalyst for younger troopers to pick up the mantle and move it forward.

T

MRC,

Thanks! I was in 2/505 PIR from 1985-88. Did we cross paths?

TLB

yes you dumb ass! 86′-92′!

And 5th Group together!

MRC,

I have never denied having more than my share of dumbass moments!

I would really appreciate it if you would get my email address from SSD and drop me a line when you get a chance. Thanks!

TLB

TLB, I just sent you an email. T

Perhaps the Army needs less PHD’s as Historians, and more people who have actually served, and then moved into the History field. People who can have an inkling of what it is they are looking at, and then properly interpret that in a way that connects history to today.

Fred,

You are right. That would be the optimum COA in a more perfect world. But people like that are in extremely short supply. The fix would be to grow our own but I haven’t seen any interest in moving in that direction.

TLB

I think there are plenty of people out there like this, but retired enlisted, with a BA or even MA in History, they just can not compete with a kid with a PHD. Sure those retired guys are going to make the list, perhaps even interview, and not be selected…….Ask me how I know.

I’m not a fan of history and hate to read. While I can 100% appreciate how knowledge of military history could benefit service members/leaders, I believe the biggest failure happens because the military is not able to change quickly enough based upon the on ground situation. The impetus being- “it’s the way we’ve always done it” or “SOP”.

The biggest, most costly, lives lost example that I can offer is the IED threat in Iraq. Why did it take the military so long to counter the IED threat? How many lives were lost because of the inability of leaders to adapt to the ground situation and threat by NOT changing tactics?

Another example I like to recite, is when I was tasked to train with some of Special Forces most elite group- C/1/10. This was pre-war and these cats were running around with 12 magazines each, why? Because of “SOP” which was based off of what happened in Mogadishu. I asked them to change their SOP and was told “we can’t- it’s our SOP”. They were also running around with inadequate door charges (not full length) and carrying the charges PRIMED. When I asked them about this, again “SOP”.

My point is, while I can appreciate history, I think the real game changer is developing leaders that have the foresight and ability to quickly adapt to the ever changing threat and environment as apposed to a well read commander.

A historical study of IED’s is what promoted the widespread use of MRAP’s. South Africa developed them in the early 60s to mid-70s to combat the same type of IED threat that we faced.

If key leaders had a wider appreciation of history MRAPs may have shown up sooner.

The lack of a deeper and comprehensive understanding of history is why some units rely on just their recent combat experience hence the 12 magazine SOP. Nothing in war happens for the first time. There are historical examples for everything. Knowing those various ways allows one to find different solutions to “new” problems and become adaptive leaders.

Understand your dislike of reading. I didn’t like running. I overcame it by finding different ways to run that I enjoyed. While reading is a powerful way to transfer data that hasn’t been improved upon there are other ways to study history. Find a medium that works for you.

The MRAP was too little too late.

Unit’s drove around the countryside in daylight, for years. Unit’s conducted operations in daylight, for years. Those aren’t problems solved by a piece of equipment.

Before fielding any new piece of equipment, there’s usually a question asked to find out if training or change in tactics would fix the problem. The MRAP was and is a great thing and helped solve the problem of unit’s driving around in daylight to conduct daylight operations.

I did numerous tours abroad, on multiple continents. I could never understand why when out operating in hours of darkness, we would never run into any conventional forces.

At the Unit in which I served, we quickly changed tactics to stay ahead of the enemy. That saved lives.

Will, I’d like to say I agreed with you, but your first paragraph there? You’re wearing rose-tinted welding goggles.

Precisely NOBODY in the Engineer School was looking at the MRAP. They procured a set of the Route Clearance vehicles for the Humanitarian Demining Center, and then after some half-ass testing, let that gear rot on the tarmac there at Fort Leonard Wood. Even during the early stages of the IED campaign, they were doing jack and shit to get that set of gear refurbished and sent forward to Iraq.

The story I got is that some Major who was familiar with the fact that the Humanitarian Demining Center knew about the set, and he committed career suicide by taking the issue to his Congressman, who started asking some rather rude questions. Otherwise, that gear would likely have never left the states, and procuring more of it wouldn’t have happened.

As late as January of 2004, I was in Kuwait stripping re-deploying units of their armor blankets to send up north for our guys doing route clearance in the northern half of Iraq for 4th ID. Before those kits got sent up, we’d been operating our route clearance teams in fucking sandbagged HMMWV and FMTV vehicles, with bolted-on bullshit we’d scrounged out of the various industrial yards in Kuwait and sent north. Some of those units were smart enough to cannibalize the Iraqi armor for plate, but making it all work…?

We told those assholes they needed to buy armor kits for the FMTV concurrent with the fielding/purchase. We told them the cab-forward design was stupid cubed, for IED work. We were ignored, and it wasn’t until about our second tour in 2005 that a lot of that gear finally started flowing into country.

Utter. Fucking. Bullshit. We told them; they blew us off. And, there’s never been the least hint of an investigation, or even “intense self-examination”. You go read the official bullshit histories, and they all say that we “…were taken by surprise…” by the IED campaign. That’s only true if you were fucking brain-dead, and ignored every fucking conflict world-wide since the opening phases of Barbarossa–Because, baby boys, the whole doctrinal framework for this kind of war was laid on the Eastern Front by the Soviets during the later part of the war. And, of course, we ignored it. Even after Korea, even after Vietnam.

Here’s a little tidbit: The South African and Rhodesian experience with IEDs and mines out in the rear areas was entirely contemporaneous with our experience in Vietnam. Small wonder, that–The same people were doing the training of the insurgents.

Rhodesia and South Africa, not having the buckets of cheaply-replaced draftees that we did…? Well, they built all sorts of specialized armored vehicles and detectors, stuff that they did under international sanction and out of motherfucking railway repair depots. The US Army? LOL… Fuck me to tears, it makes me weep. One of my first bosses lost his shit with a full-bore Vietnam flashback out there along Cowhouse Creek at Fort Hood, because the clearance exercise we were doing reminded him so much of one of his in Vietnam. He’d lost like six guys out of his squad of eight, and he remembered watching them lay out there on the road and bleed out, because they couldn’t go recover them while they were alive. See, the VC (or, whoever…) had taken to going after the morale of the route clearance teams, and knew they had no real armor, so they’d hit them with a distant ambush, shoot the teams up, and then maintain overwatch while they bled out and died. Since the route clearance teams rarely had priority for any firepower, or Infantry coverage, we lost a shit load of young men keeping those roads in Vietnam open.

Note that: Most technologically advanced army in the world, and about all we’d done to improve things for that mission was give ’em transistorized mine detectors that were a little better than the WWII models. While Rhodesia and South Africa fielded multiple generations of specialized equipment that dropped their casualty rates to damn near zero, and broke the back of the insurgencies IED campaign.

Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

And, people wonder why I’m such an angry man over this and similar stupidities. The majority of this crap is entirely preventable, and could be mitigated with some forethought and preparation, but the people running the show don’t want to pay attention, or fix shit. It’s too “risky” to their rice bowls, and while there should have been a full-scale Congressional hearing on this shit, there was basically nothing. Those assholes all have their jobs, or retired with promotions, mouthing hypocrisies about how “…much they did for the common soldier…” while on duty.

Gentlemen, the subject is the study of history and its value on leadership, training and professional development.

Comparing the operations of special ops and conventional units can be misleading if they aren’t the same mission. Were special operations doing presence patrols, securing LOCs, cordon and search etc. in the early years of Iraq and Afghanistan? While combat patrols should leverage our advantage in night vision if the mission is presence or security patrols to influence a population it may make sense to do them when the population is awake. It’s also a mistake to generalize one’s personal experience across a whole theatre or across al units. I never saw special ops units in my area of operations. It would be a mistake to say they contributed nothing. Finally we did recognize the threat was different and we made huge changes to the way we did business. The COIN manual is written by two leaders with a profound understanding and sense of history, Petraeus and Mattis.

Citing the lack of MRAPs in ’04 less than a year after the invasion doesn’t prove the case that current MRAP’s weren’t developed without an analysis of the past. Nor is limiting the argument to demining ops recognize the larger fielding of MRAPs. To argue such requires looking at the issue through a pinhole. Heck, the first MRAPs fielded were bought directly from the S. Africans.

How quickly does one realistically expect technological solutions to appear on the battlefield? Here’s a thought, the S. Africans fielded the Hippo in ’74 in response to the S. African Border War which started in ’66. That’s eight years of buckets of draftees.

As for assuming IEDs are always a factor in war how many did we see in WWII, Korea, Grenada, Panama, Desert Storm etc.? Sure they were used but they were not the major weapon system employed by our enemy requiring a significant adaptation to how we do business.

I’m not saying salient points aren’t being made by both of you. They are. Conventional units should leverage the night vision advantage. Faulty acquisition can be an almost infinite list. Neither prove one doesn’t need to know history to be an impactful leader/trainer ESPECIALLY at higher levels of responsibility.

You’re missing the point. Equipment doesn’t solve ALL problems. Training and changing tactics are the first step in solving a problem. If training and tactics CAN’T solve the problem, then new equipment might fill the void.

Presence patrols. What is solved by this? Is it a tactic that served us well in the GWOT?

Similarly to Vietnam- Establish a base. Patrol around the base. Defend the base. This is an antiquated way of fighting a dynamic enemy don’t you think? Does it work? What does history tell us about conventional forces engaging with enemy in that manner? Why did we employ that tactic in Fallujah?

Another GWOT example- Fallujah. Was once a calm area while in control by the 82nd Airborne. Handed over to the Marines, it became a total shit show. Marines had to “re-take” the city that had been previously US owned territory. What tactics did the Marines employ and how well did that work out?

I’m not throwing blame. I’m pointing out that we tend to employ tactics that didn’t work well the first time around because “that’s how we conduct xyz”. We can ALWAYS do better.

Don’t get me started on the whole IED bullshit. There was precisely zero fucking excuse for our lack of preparation, because I know for a fact there were people telling the powers-that-were in the Engineer School that we’d be facing that issue, and had better prepare to deal with it. How do I know? I was one of them.

35th Engineer Brigade is the formation that most of the civilian staff of the Engineer School serve in, and they were slated to fall in on I Corps as the Corps Engineers. I knew most of the folks in the school structure because of that, and I raised the issues with them, all the damn time. We had an exercise where they were looking at the moving pieces to put troops into Rwanda, and the facts of the matter became horribly plain–The roads from the ports into Rwanda were all heavily mined, and basically useless without clearance. The TPFDL had the Engineer units that would need to do the work arriving well after they should have been there, and the mess created by all that was incredible. That, and the fact that in ’93, we were still using Vietnam-era techniques that nobody had even trained on in years, let alone evaluated with the new MTOEs and equipment. I was literally the only person in the I Corps Staff Engineer Section, the active duty part, who had ever even done training on the mission, and that was as a private back in the early 1980s. These guys were blithely hand-waving the route clearance mission, and my boss and I were looking at each other like “How the fuck is this supposed to work? There’s like 2,000-3,000 km of MSR we need to clear and patrol, and the goddamn mission can only move at the fastest a 12B10 can walk in front of a sandbagged 5-ton. These idiots were taking the total lengths of the MSR, dividing them by the rate of clearance, and just assuming that we’d be having every engineer unit in theater out there clearing their little part of the task, all at once. There was no provision for getting those guys out there, or supporting them–They just pulled out the Staff Handbook, did some math, and waved their hands in the air.

More than likely, the resulting mess at the SPODs would have made the backed-up cargo at Kuwait in 2003 look like a cake-walk. It would never have worked, and in the aftermath of the exercise, whose outcome pretty much told the State Department weenies who were participating that there was no way to intervene in the genocide without doing a year’s worth of logistic buildup, my boss told me to start researching for him.

I went digging, interviewed vets who’d done route clearance in Vietnam, got historical reports out of the libraries that hadn’t been checked out since the library accessioned them, and started looking at everything I could on the subject. We dropped a paper on the schoolhouse through our contacts in 35th, and waited. Upshot? We got told, through the grapevine, that the Engineer School “…did not want to develop that capability, because if we could do it, someone would… Ask us to do it”. And, the budget wasn’t there to support buying new, modern equipment.

The fucking assholes were warned, and it wasn’t just me, or my boss, who retired in the mid-nineties. There were other attempts, after Somalia, and one of them was my company commander over in the HHC of 14th Engineer Battalion. We got wind of the choices and designs that they were doing for the FMTV, and we looked at the cab-forward design that puts the first axle (most likely to trip the charges or mines…) right under the crew cab, which wasn’t armored. The South African SAMIL range of vehicles, on the other hand? Armored, conventionally designed, and the front axle is about three-five feet ahead of the crew capsule. We pointed this out, and the response from TACOM and the project manager…? “We do not foresee ever having to operate in the sort of environment that these expensive features would require…”.

I don’t like to think about how many bodies there are on this whole range of failure, dating back to at least ’92-’93. Mostly because, some of those bodies were my troops, and I feel like I failed them by not getting this shit fixed before they turned out to need it.

That HHC company commander I reference above? Yeah; he’s another one the Army drove away, having taken early out in ’95 or so, once it became apparent that they weren’t even going to give us the extra radios, machine guns, and personnel we’d need in our HHC to do our fucking support job. All the work, all the staff time, all the papers we wrote? Complete wastes of fucking time. And, you know what? After the 14th got alerted to go into Iraq with 4ID in 2003, the run up to the deployment had us raping every ash and trash unit we could on Fort Lewis, to “plus up” that HHC to what we’d said we needed almost ten years earlier.

Anyone who says we were “surprised” by the IED campaign is full of shit. They were warned, they just ignored the warnings. We handed them the solutions they eventually implemented, damn near down to the proposed MTOE structures, and then acted like it was all their fucking idea in the first place.

I don’t know how many died because of that bullshit, and I don’t want to know, but I know there were a bunch of entirely unnecessary casualties, as well as the fact that the war nearly pivoted on that campaign. Had we been listened to, and the preparatory precautions just been taken, like as not, that flank we offered up wouldn’t have been there, and the IED campaign might never have gotten as bad as it did. Our lack of preparation enabled their early success; had they run into properly prepared US forces, they would have experienced failure, and gone on to try something else, something that might have been a lot less dangerous to our guys.