As I said in the comments in the Fighting Load Continuum (FLC), Part II, if I accomplish nothing else, I am hoping these articles will re-energize leaders’ emphasis on soldiers’ loads similar to what some of us experienced in the late 80s “Lightfighter” era. That focus in turn will presumably empower young leaders to make smarter decisions about what to carry and what not to carry. Carrying ONLY the mission essentials may or may not result in appreciably lighter individual loads, but I am making the argument that inculcating strict load discipline habits will assuredly enhance the unit’s chances for mission success. Bottom line up front, combat loads are both an enabling and debilitating mission factor that deserves much more active leadership attention then it is now receiving.

As we have already noted, the Army has a long-standing aspirational combat weight goal that it freely admits cannot realistically be achieved. Accept that fact but do not be afraid to attack the problem anyway. Be aggressive and do what can be done to lighten your unit’s load because it makes tactical sense. New technologies do tend to add weight – but also provide critical new or better capabilities. We talked about body armor specifically last time; good leaders prefer to bring people home alive – if not perfectly intact – so we accept the capability and the tradeoffs that body armor represents. Remember, human nature being what it is, unless ruthlessly controlled by leaders, units and individuals will ALWAYS carry as much as they can get on their backs “just in case” when going into combat.

A risk is a chance you take; if it fails, you can recover. A gamble is a chance taken; if it fails, recovery is impossible.

Erwin Rommel

Leaders cannot realistically avoid taking risks with soldiers’ lives in combat; however, leaders must do everything possible not to gamble with those lives. In terms of load management, the risk incurred is directly proportional to a unit’s ability to recover if a planning assumption proves to be mistaken. For instance, food and water are important to sustain combat power, but a temporary shortfall of those commodities is not likely to cost lives or have an immediately catastrophic impact on a mission. That is even true if the mission is unexpectedly and unavoidably extended or changed.

I will use a scenario based on a number of real world incidents to illustrate. Let us say a patrol (mounted or dismounted) went out in the morning for a short pre-scheduled meeting with a Host Nation counterpart. The meeting goes as planned, but on the way back a vehicle rolls over into the river – or perhaps just one soldier falls in and is swept under. Like it or not, the emergent recovery mission is now of indefinite duration. Still, if the patrol brought limited water or chow with them, it is of no great concern because remedial action is relatively easy. The patrol can make do until additional supplies can be delivered to them by vehicle, air or on foot if necessary. Sure, some stomachs may growl or mouths get dry before resupply gets there, but the situation remains low risk throughout. Indeed, our logistical system is optimized to rapidly deliver bulk consumables like water, food, and ammo.

On the other hand, if the patrol left behind Night Observation Devices (NODs) because they expected to complete the mission well before dark, that situation would be much more potentially dangerous. Recovery from that decision would be a lot more difficult and a low risk mission can quickly become high risk or even a gamble. We issue NODs individually and do not have many replacements on hand; therefore, they cannot be stockpiled and readily available like water, food, and ammo. Imagine the remaining soldiers of the parent unit trying to search individual bags and tuff boxes to collect NODs left in the rear and deliver them to the patrol before nightfall. A herculean task that – while not impossible – is best avoided. That is why I often use NODs to explain the “Gilligan’s Island Rule” mentioned in Part I. In short, it is rarely prudent to leave NODs behind even if the original mission is supposed to be a routine, daylight, “three hour tour.”

I also mentioned last time that I always cringe a little when I hear combat loads being compared / equated to civilian backpacking – even extreme forms of backpacking. While both involve packs, they are apples and oranges. An ultra-light enthusiast or even someone trying to summit Everest may be pitting himself against unforgiving nature. However, he is not also simultaneously moving to engage and destroy armed opponents that are intent on killing him first. Likewise, a civilian backpacker generally carries only his own gear and supplies. Conversely, soldiers always hump two categories of gear into combat, stuff carried to support him or herself, and – usually considerably more – stuff carried that is intended to support other members of the team. To that end, a combat soldier must always pack items in a manner that effectively supports the unit mission and his teammates – rather than for his own comfort and convenience. Beyond that, a soldier’s mission is not just to get somewhere and back. A soldier strives to get there, win the close fight with his team, and get back alive. That alone is the ultimate goal of combat. If a lighter load facilitates mission success, great. If a heavier load is needed to get the job done, so be it.

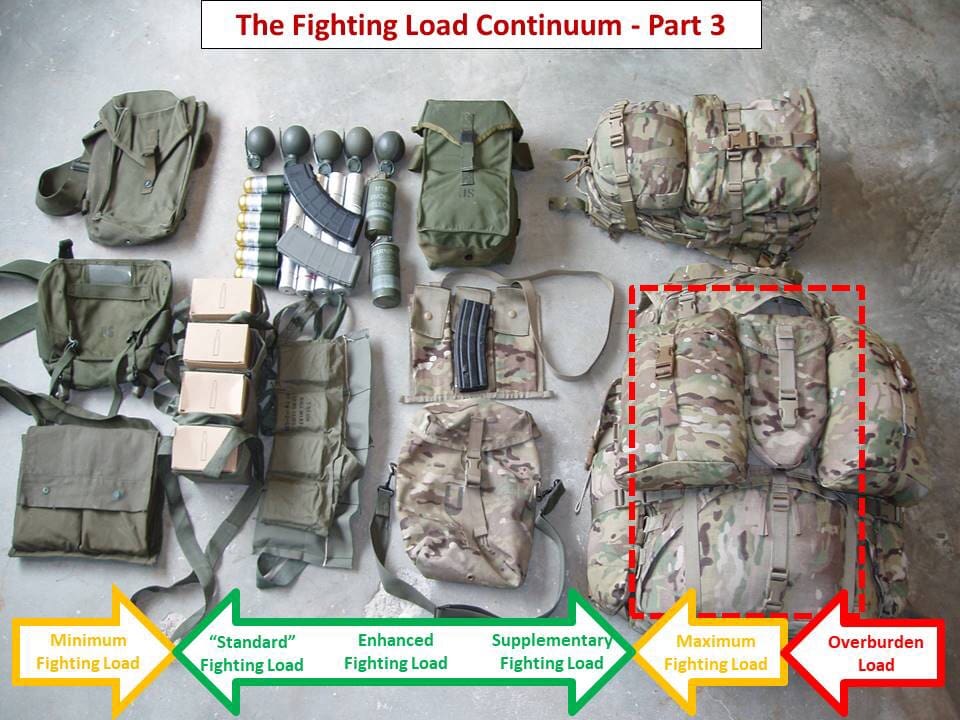

Appropriate packaging and packing of team materiel facilitates transferability and helps speed up mission transitions. The packaging of combat loads starts with distributing essential capabilities between the individual’s “fighting load” carrier, rucksack and assault pack. An additional challenge of effective load management – at the high end of the FLC especially – is not just about limiting the weight but also the bulk of a combat load. There are sound tactical reasons to keep the “cube” of any rucksack within the limits I have outlined in red on the large Molle rucksack in the attached picture. It is desirable that the pack dimensions not extend more than a couple of inches above the shoulders, much lower than the end of the tailbone, and no wider than the shoulders. Why is that? Easy, so the soldier can always fit readily through a fixed wing aircraft’s jump doors, down a ship’s passageways and – even more common in combat – thread through residential doorways, hallways or stairwells and still fight effective with a rucksack on if necessary. Note, I have purposely “inflated” this sample rucksack beyond the desirable size range – fully recognizing that overloading is more common than not.

Assault Packs and the Army issue Medium Rucksack provide smaller options that may be suitable in limited cases. Assault Packs like the one displayed (top right) in the attached picture are sized to carry an ASIP Radio (not shown) and accessories and can be used to carry other signaling devices like flares, smoke grenades, and visual or thermal panels critical during actions on the objective. Of course, additional ammunition for machineguns, some breaching tools, or demolitions might also be carried in these relatively small packs if needed. Similarly, some additional water and perhaps a singular piece of snivel gear might be loaded. Generally, there would not be room for substantial food or sleeping gear in this echelon of the FLC. Therefore, the “Assault Pack Load” alone is not going to be adequate for missions planned to extend beyond 24 hours. I would submit that despite falling into the so-called “3-Day Pack” category, the Medium Rucksack alone would probably be inadequate for a mission beyond 48 hours. Realistically, even filled to capacity including sustainment pouches, the large Molle and the FILBE rucksacks will still not get a unit much beyond 72 hours without at least a resupply of water and batteries.

As many of us have experienced in the past, when new “lightweight” gear has potentially reduced combat weight, the almost instinctive tendency is to use that “savings” to now carry more of something else. I suggest rejecting that understandable but counterproductive reaction. If a leader did not consider “something else” mission essential before, why is it mission essential now? It still sounds suspiciously like “nice to have” to me. For a time in the 82nd Airborne Division, I was a mortar platoon leader in a rifle company. We had both 60mm and 81mm mortars – 3 tubes each. The 60s (and their ammunition) were obviously the lighter option. If my platoon was tasked with harassing and interdiction (H&I) fires the 60s would do. However, if the company was going to be attacking a dug in enemy, the 81s were clearly the better choice. In short, because they were much more effective, the company humped the 81s more often than the 60s – despite the considerable extra weight. I say “the company” because, while the Mortar Platoon could haul the tubes and associated items, one or more of the Rifle Platoons had to carry most of the ammo. The reality of that considerable shared burden helped squash any inclination to seriously consider carrying any superfluous “nice to have” items.

Let us focus now on enhancing the packaging and transferability (P&T) of some common items in a combat load. At the bottom left of the attached picture is a claymore mine. It is the perfect embodiment of P&T. Everything needed to make the mine go boom is consolidated in the provided pouch. It is packed in the factory that way. It even has instructions with pictures on an inside flap just in case. This pouch can be readily carried internally or externally on any size rucksack. The claymore is not likely to be employed in an assault, but rather in the defense, after an objective is secured, or to deter pursuit in a break contact situation. When needed, the owner can disconnect it from the ruck, use the integral strap to carry it independently and / or pass it to someone else to employ – quick and easy. Unfortunately, not every item the military issues is so inherently P&T friendly. It behooves units to reconfigure those items into logical packets similar to the claymore example prior to launching on a combat mission.

Some of this is probably a no brainer for people who have been doing it for a while. However, it is not something units do consistently well unless the leadership is paying attention. For instance, a radio should always be packaged with antenna, handmike or headset, and batteries even if it is only a contingency backup to the primary. If the radio is passed to someone else to use or just to carry, everything should stay together and the system constantly remains fully mission capable. As a side note, when talking about electronics or weapon systems especially, it is obviously preferable that whoever is carrying the item have enough training to put the item into operation and use it effectively in an emergency. In other words, it was necessary for the 11B (infantry) paratroopers I referenced above to hump additional mortar ammunition but it would make no sense to task them to carry the actual mortar tubes into battle.

In the picture, I have displayed some of the old school P&T items and the current ones that a unit can still acquire. For many years, I carried the canvas “Bag, Carrying, Ammunition, M1,” a.k.a. the General Purpose (GP) Bag (top left) and the associated GP Strap. They date back to just before WWII. I bought this one, dated 1951, at a surplus store in Tacoma, Washington in 1979 and carried it for most of the rest of my career. I also jumped it many times. Usually, under the top flap of my Alice but also exposed for airfield seizures without a ruck. Inside would be star clusters, smoke grenades, binoculars, and in the late 80s a unit purchased sabre radio. Much like the claymore pouch, I could quickly separate this bag when I dumped my ruck and retain only the critical items I needed immediately. Additionally, since my troopers knew this was where I kept my most mission essential leadership stuff, if I went down they could readily grab the bag and continue the mission without me.

Those canvas GP Bags – and the equally rare nylon versions from the late 70s (top center) – as the name suggests, are great for general ammunition haulage. Numerous fragmentation or smoke grenades, 40mm rounds, loaded magazines of any caliber, bandoliers, machinegun belts, and so on, fit neatly inside the bag and can be dropped off and recovered easily and as often as necessary. Unfortunately, the GP Bags were no longer standard issue or readily available in the late 70s and 80s. Therefore, we used the ubiquitous buttpack (left center) with GP Strap in exactly the same fashion instead. As I recall, it was common practice for machinegun teams to leave a 50 round “starter belt” on the gun and backfeed ~250 rounds into buttpacks. The gun crew would carry what they reasonably could and – depending on how much ammunition needed to be carried – additional buttpack loads would be distributed to other members of the platoon. Indeed, buttpacks worked well for all the smaller munitions, but were not deep enough for parachute flares and star clusters. That is why I always personally preferred the GP Bag.

For some reason, simple pre-mission P&T preparation seems not to get the emphasis today that it did in years past. The GP Bags and the buttpacks are gone. There are only two standard issue items that I know of currently available to potentially address this recurring challenge. One would be sustainment pouches with GP Strap as shown (center bottom). While not reinforced the way the GP Bag was, the Molle and FILBE sustainment pouches have the volume to perform the same function. But, the FILBE pouch has no strap attachment points. And, unfortunately, the Molle pouch design is seriously flawed. The D-Rings on the side that the straps attach to are much too low. To be effective, the rings would have to be moved up at least 2 inches. The Army and Marines do issue a 6-magazine bandolier (center). I liked to use these to hang extra magazines in a vehicle; however, I do not care for them as a general purpose P&T tool since they are useless for anything other than M4 magazines. In combat, constantly feeding the crew served weapons is usually much more of a priority than replenishing individual riflemen.

Can approaching the combat load challenge from a different angle, such as I am suggesting with the FLC concept, really facilitate junior leaders making appreciably better tactical load management decisions? I certainly believe it is a sounder place to start. It is surely worth an honest try. How we choose to frame a problem trends to limit or expand our suitable solution set choices. In the case of combat, winning the fight with the fewest possible casualties must be a leader’s priority and objective. As I have said before, he or she must think first in terms of minimum mission essential capabilities and avoid obsessing simplistically on load weights. In Part IV, I will be discussing leader tools already available like SOPs, inspections, and rehearsals that can be either enablers or obstacles to effective combat load management – depending on how they are used or misused.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

An aspect here that I think needs to be highlighted; combat load is dictated by tactics and operational considerations that we often don’t take into account.

Leave the wire with the idea that you’re just doing presence patrols, and will deal with everything that comes at you–You’re going to need to be prepared to deal with literally anything that happens. Cede initiative to the enemy, and the unintended consequence is that the combat load is gonna be huge.

Leave the wire with a specific target, time, and place for your action, retaining the initiative? Your combat load can be whatever you like. You’re making the choices, and while you have to account for sheer mischance, you can still control what you’re going to carry.

I’d submit that the larger problem we have in terms of combat load during the last several wars is that we’re letting the enemy choose when and where the engagements are going to happen. We let them refuse contact by the virtue of how we set our ROE and our tactical/operational plans. Thus, we’re breaking the backs of our troops, expecting them to haul everything they need to deal with anything they might run into…

“I’d submit that the larger problem we have in terms of combat load during the last several wars is that we’re letting the enemy choose when and where the engagements are going to happen. We let them refuse contact by the virtue of how we set our ROE and our tactical/operational plans.”

BOOM! Truth bomb.

Kirk,

Good points. I agree. Remember the old saying that “he who tries to defend everything defends nothing.” I would add that he who tries to be ready for everything is ready for nothing.

That is what I saw far too often in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soldiers and tactical leaders with no clear understanding of their mission or the higher commander’s actual intent – assuming a clear intent had ever been articulated. So, when they left the wire, they took a lot of stuff “just in case” of “something” but were not actually prepared to do anything…other then leave the wire and eventually return.

I also saw this attitude much too often from junior leaders and even some not so junior leaders. “My mission is to bring all my soldiers home alive.” That can be your laudable goal…but, no, it is not your mission. Of course many of those same confused leaders babbled about “taking the fight to the enemy” in the next breath.

You cannot give soldiers contradictory orders like that and expect positive results. And guys like me – middle management if you will – MUST translate all the strategic and operational nose bleed guidance into understandable and achievable tactical tasks for those junior guys to execute.

No soldier should ever go “out of the wire” without a clear understanding of the mission. And, consequently, he should understand why it is mission essential that he carry every ounce of gear on his back or in his vehicle. If he does not know, that is a gross leadership failure.

TLB

I agree that part of it is the lack of a clearly understood Commander’s Intent, but the bigger issue I’m trying to get at is what is forming that “Intent” in the first place.

Commander has a nebulous idea of what he’s doing, he isn’t going to be able to clearly state what he wants, and even if he can articulate it, then the problem shows up in the entirely nutso way we’re conceiving these operations in the first place.

If you go out of the wire with the intent of “Let’s see what happens…”, conducting “presence patrols”, then your whole mentality is off. You need to step back, and figure out how you can have the initiative, vice dangling the troops out there to “have something” happen to them.

It’s the difference between “We’re gonna go out and draw fire” as opposed to “We’re going out to kill X and Y and Z, we’re doing it here, with these weapons, at this time…”.

The first concept of operations leaves the choice of when to engage, how to engage, and everything else up to the enemy. The second puts it back on our side, and from that, you can start to set your loadout with a bit of sanity.

Incoherent strategy flows down to create incoherent operations using incoherent tactics. No “Commander’s Intent” in the world, no matter how well understood, can overcome the essential nuttiness of using your troops like so many little cat toys dangled in front of the enemy to get a reaction.

Frankly, I think a lot of our supposed problems stem more from the operational end of things than anything equipment- or SOP-related.

That said, I’d like to get in touch with you directly. Is there a way to do that?

Kirk,

Sure, you send your email to SSD: admin@soldiersystems.net and they will forward to me. I will shoot you a note back.

Since others will see this I will add this personal admin note. I did have one puzzling contact with a reader recently. Some kind of “bait and switch” apparently. One fellow contacted SSD, I responded to him and then someone by another name answered back asking me to evaluate some sort of “load carriage system” he had invented. When I asked him what was the deal with the two names he never responded. I have not heard from him since. Not sure what was going on there but it clearly was not legit.

However, that is the one exception I have encountered so far. Bottom line, I do not mind being contacted by anyone that wants to discuss any of the things I have written or to talk about gear or military service related issues. Several folks have done that in the past. I can almost always make time to have those kinds of conversations. The benefit of being retired.

TLB

I rather wish the Army had had the wisdom to keep all of us on AKO, rather than shut that down. There’s a lot of knowledge out in the retired ranks that they could be taking advantage of, but… Let’s save some money, and disconnect ourselves from a wealth of knowledge and experience…

Penny-wise, pound-foolish. That’s my Army.

Sorry for the thread diversion, but that shutting down of AKO was preceded by kicking retirees off almost immediately. Soldier for Life, eh? If anything, retirees should have maintained an account for 3 years and guys ETSing at least 2 years (for the contacts, references, etc.).

LTC Baldwin, on your bit about civilian backpackers, I’d also offer that the civilian backpack can often fail with little consequence. For an infantryman, that pack has to last for months. We cannot reduce a certain amount of robustness without (potentially lethal) significant risks. That robustness equals weight.

Great write-up – I’m late to the show and read all three parts. I don’t agree completely on the ‘always have NODS’ stuff, especially if our enemy doesn’t. We did fine for a long time without that tech, and in the defense, it isn’t always the absolute showstopper it could be, especially if you can call for illum rounds.

Tankersteve,

Sure, we made do without NODs back in the day – because we didn’t have a choice. I would say that NODs are even more important if your enemy doesn’t have them. In that case, NODs give us a clear tactical advantage. Why make it a fair fight. Visible spectrum illumination rounds work both ways. When we light the place up we also make it easier for the enemy to see and more effectively engage us too!

I agree with you that military gear is usually of heavier gage construction for durability. Modern materials are coming on line now that are lighter, stronger, and do not absorb moisture either. Some options are still relatively expensive compared to standard old fashioned cordura, but change for the better is fast coming.

TLB

Spot on…

I have spent last 10 years being deployed and came up with very simple conclusions:

– On most dismounted patrols, I would happily ditch my body armour and helmet and wear old webbing or assault vest with hat instead (ESPECIALLY during patrols when we got shot at). It´s no secret that we (coalition forces) do not manuever with dismounted troops anymore when under fire. We just drop like sacks of potatoes, return fire, and wait for CAS and mounted QRF.

– Losing war is more acceptable nowadays than being accused of violanting enemy´s rights.

– Protecting soldiers with all sorts of armour and expensive gizmos makes them so heavy that they have to be driven, and then killed by IEDs. Our solution?? Add more armour and more gizmos!

The MOLLE IV bag bandolier from the Mike bag may provide a little more versatility but still lacks a flap closure.

For Marines the Gen1 ILBE lid is a pretty versatile piece- nice size main compartment and PALS attachments underneath. It can be rigged as a sling bag with the addition of a 1″ webbing strap and two male QR buckles.

TuffPossum makes some interesting flat centerzips. I use one for additional medical in the slot pocket of an LBT 3-day.

Great high-quality article/series: keep it up. There seem to be two persistent issues that need to be dealt with: command-directed gear lists (notably the aforementioned body armor mandate) and the need for more [specialized] training. It seems clear that the best-trained and best-led units would tend to have the least number of issues with combat load. Eliminating bad equipment choices due to poor leadership/inexperience and lack of realistic, individual training needs to be the top priority. When it comes right down to it, there’s a tendency to accept that leadership and training are immutably subpar, even in SOF. I’ll go out on a limb and say that formalizing and integrating some form of “combat load” COI/POI’s, or at least a formalized approach to training “specialized combat load” in all schools and training would be a first step. By this I don’t mean standardized gear lists but instead finding a way to hammer the hard-won lessons-learned when it comes to deciding what we carry in various missions, environments and conditions, and making sure adequate time and priority is given to ensuring the students understand and retain essential knowledge. The current approach at the “schoolhouse” is most often a gear list from the instructor(s) which for the most part is solid, especially in the more specialized schools/training (though this reinforces the practice of the centralized, disseminated command gear list). Ideally, that gear list is refined throughout the duration of the training until the individual [when allowed] finds what works best for the mission….and hopefully the individual can remember/retain these LL’d for the dozens+ of courses/schools he attends and apply this downrange (but recall can be a bitch). The very best training I’ve seen in this is during contracted SME military mountaineering/cold weather training (differentiated from civilians with no combat experience offering valid, though recreation-based, techniques training) where equipment use and selection is given a surprising amount of time throughout the course so the students can gain expertise based on very specialized and relevant military experience. How we bring this training approach to everyone headed downrange should be a priority.

…and to this I should add that once folks (and this of course includes/emphasizes the increasingly keyboard-bound higher chain of command who need to (a) have confidence that they can delegate these decisions and/or (b) have enough relevant experience to make good decisions themselves) are trained and experienced enough to be capable of identifying the “right” combat load for the given mission, this will logically be the “light” combat load.

Disclaimer: i’ve been in both the large unit (gear list including accumulated inputs from the CG/CSM down 6-levels to my team with implied 30lbs of extra CYA kit) and small unit (word from the boss to make sure to include “this and that” with his implied “don’t F this up, I was told to shut up and color myself”).

Good article. We are still talking about load management (weight we carry), but let us see the comparisons of what we did carry in weight in the 1980’s and 1990’s for a typical infantryman in a mechanized, airborne, and air assault unit to what is typically carried during the last 15 years of fighting. The weight carried by an infantryman in the 1980’s might surprise a lot of future leaders. Let us not forget the main idea that is lost today in many units is mobility of a squad or platoon. More weight carried decreases you mobility and combat effectiveness overall. Did having MOLLE/PALS gear improve the individual infantryman?

Army pushes 6.8 Overmatch into service to penetrate Russian armor.

Russians ditch armor and increase mobility since 6.8 or 7.62 or 5.56 have the same basic effect on unarmored personnel.

Getting flanked is worse than a bullet not making it through the enemy’s front plate.

Minor foot note on sustainment pouch shoulder bags; I’ve used several over the years and the fix is the simplest thing in the world. Remove the d-rings from the sides (why are they even there?) and thread them through the top set of MOLLE mounting straps. They are now at the top edge of the bag and on the user side of the pouch rather then the sides; basically the optimal location.

Luke,

Sounds like a pretty good gear hack. I suggest that you find an extra pair of d-rings rather than do surgery on the issue sustainment pouch – if you ever intend to turn the pouch back in. The d-rings on the sides of the pouch was supposed to let you use it as a stand alone GP Pouch – except that they are very poorly positioned for that function.

James (above) mentions the IV Bandolier that comes with the medic bag. The Molle radio pouch that goes inside the large ruck can also work but does not have a top flap either. I believe your suggestion will work fine for light loads. But those attaching straps are held on by a single bar tack and are not meant to carry the entire weight of the loaded pouch. I suggest getting them reinforced if you want to use them as you described with serious munition loads.

Of course, the Army could just make an A1 version of the sustainment pouch and move the d-rings up AND reinforce the attaching straps so the pouch could be carried effectively both ways.

TLB

An examination of the British load-carrying systems might not be a bad idea; they already do something quite similar to what you’re suggesting.

I think the Army rather badly needs to do some work with all of the logistics “stuff”.

Why, for example, do we spend billions shipping things into theater on wooden pallets, inside cardboard boxes? And, then have to pay to either ship them back, or destroy them? Why the hell aren’t all of our logistics packaging materials repurposable for things like building field fortifications and shelters?

Conversely, why the hell are the rations packed in boxes and plastic pouches? Wouldn’t it make a lot more sense for the outer packs to be like ammunition bandoliers, and be semi-disposable? Why aren’t there trash bags and other necessary things for field sanitation included in the boxes?

If nothing else, we should have “resupply kits” as a part of the standard field set-up, to where you can order up a platoon-level resupply kit that you can have configured in the rear, and then use to do a rapid resupply run, where you’d package up the appropriate number of meals, the water, and all the rest into preconfigured loads that the platoon could literally just stick into their sustainment pouches on their rucks as soon as they’re handed over. Say, three meals, some hygiene items, those disposable water pouches, and so forth. That way, you’re not having to have guys spend time breaking down meals, filling canteens, and all the rest of the delay-creating impedimentia of a resupply.

If we were smart, we’d have two sets of sustainment pouches, or inserts designed so that you could fill them in the rear, and then just do a trade-out in the field.

If we were smart, we’d handle ammo the same damn way–Instead of doing a break-bulk reload on the tanks, it’d be like an MLRS reload: Drive up, drop the old empty racks, pick up new full ones. If we had any sense, those racks would have room for things like rations, water, and packaged POL products. One-stop shopping for sustainment, no need to spend a couple of hours doing retail-level resupply.

Things have to be on wooden pallets. If you don’t believe me, store a bunch of stuff directly on your garage floor for a few months. Report back with the results.

As for your other idea, the MRE is already self contained as packaged. The fact that Soldiers reconfigure them would lead one to believe that they’d do the same no matter how they were packaged. Same goes with everything else.

You’re obliviating right past the point… You’re already shipping the pallets into theater; why the hell not make that pay for itself by using that cube/weight for stuff that can be repurposed for other critical uses?

Case in point: Why the hell aren’t the ammo can wraps built out of weatherproof material and designed so that they can be repurposed as mini-Hescos? Same with the MRE cases; build those out of something that doesn’t dissolve when wet and can be interlocked like LEGOs?

You’re going to ship that crap into theater anyway, so why not make it stuff you can reuse for other purposes like field fortifications?

The MRE pouches ought to at least be resealable in the field so that you could reuse them as trash bags for the meal, or as crap bags for sanitary disposal of human waste. It’s nuts that you have to have a separate supply of Ziplocs when you’re in a hide position.

All I’m saying is that there are a lot of places in the logistics chain where we should be examining the basic premises and saying “Yeah, we could totally use these pallets as duckboards, if we designed them for that in the first place…

The fact that we have to burn or pay to dispose of waste that mostly consists of packaging in-theater is nuts. All of that stuff should be made so that it’s reusable for other purposes.

Kirk,

I agree with the resealable MRE packets. Still, right or wrong, I think the trends are actually moving in the opposite direction. Military logistics are more and more using off the shelf solutions. UGR meal packs are one example for Class 1.

So the packing and shipping material received is going to be whatever the industry standard is for that commodity – with the exception of ammunition. The military is not likely to fund a more expensive custom packaging option for what will still be consumable / disposable items.

The old Field Fortifications manual used to describe how items like ammo crates could be used to build bunkers, etc. The SF A-Camp manual did as well. Not that those packing items were optimized for that purpose like you are suggesting.

SSD is right about chow. Soldiers will inevitably rat f— whatever food they are issued. I was told once there have actually been studies on the subject – but cannot personally confirm that. Supposedly, being able to at least exert some control over their chow was a small but important morale booster for soldiers in combat.

It also why soldiers still do not eat pills for nutrition like all the old Science Fiction stories said we would by the 21st Century. Humans are omnivores, but we are designed for solid food. Not to mention the socialization and comradery aspect of eating chow with your buddies.

Like I said, I cannot vouch for the science, but that all makes sense to me.

TLB

Ever see the South African ammo containers?

https://www.plasticsforafrica.com/index.php/products/4×4-a-braai/ammo-box-lid-black-detail

The SADF packed everything in those things, from mortar rounds to small arms ammo, and I’m told they stack like LEGO bricks. Haven’t actually seen that, but I see no reason you couldn’t copy chunks of the design to actually make that happen.

If the Army were to type-standardize on sub-containers like that, which packed onto the various standard pallet sizes, you’d have the basis for a very versatile system of things you could do with them in terms of field fortifications. A smart guy might even include some sort of plasticizer or concrete additive so that you could take local soil, mix it, fill the containers with it, and have it harden in place as a stable long-term unit. One could even design in channels for rebar both vertically and horizontally, so that you could lay these things out as long-term construction components.

Pack most of your consumables in these, specify pallets that can be disassembled for reuse or that were designed as components of the design, and Hey! Presto!, you’re not having to ship anywhere near as much materials into theater. I’d be willing to bet that whatever extra expenses you’re going to run into would be saved by not having to ship in CLIV.