RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. — A material from a rare earth element, tellurium, could produce the world’s smallest transistor, thanks to an Army-funded project.

Computer chips use billions of tiny switches called transistors to process information. The more transistors on a chip, the faster the computer.

A project at Purdue University in collaboration with Michigan Technological University, Washington University in St. Louis, and the University of Texas at Dallas, found that the material, shaped like a one-dimensional DNA helix, encapsulated in a nanotube made of boron nitride, could build a field-effect transistor with a diameter of two nanometers. Transistors on the market are made of bulkier silicon and range between 10 and 20 nanometers in scale.

“This research reveals more about a promising material that could achieve faster computing with very low power consumption using these tiny transistors,” said Joe Qiu, program manager for the Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command’s Army Research Laboratory, which funded this work. “That technology would have important applications for the Army.”

The Army-funded research is published in the journal Nature Electronics. The Army is focused on integration, speed and precision to ensure the Army’s capability development process is adaptable and flexible enough to keep pace with the rate of technology change.

“This tellurium material is really unique. It builds a functional transistor with the potential to be the smallest in the world,” said Dr. Peide Ye, Purdue’s Richard J. and Mary Jo Schwartz Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

One way to shrink field-effect transistors, the kind found in most electronic devices, is to build the gates that surround thinner nanowires. These nanowires are protected within nanotubes.

Ye and his team worked to make tellurium as small as a single atomic chain and then build transistors with these atomic chains or ultrathin nanowires.

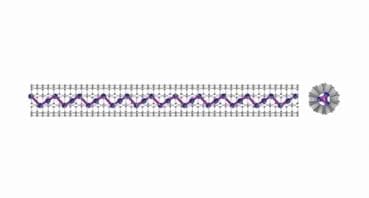

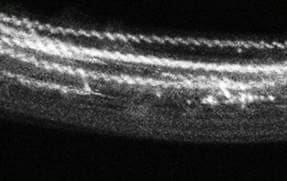

They started off growing one-dimensional chains of tellurium atoms, and were surprised to find that the atoms in these one-dimensional chains wiggle. These wiggles were made visible through transmission electron microscopy imaging performed at the University of Texas at Dallas and at Purdue.

“Silicon atoms look straight, but these tellurium atoms are like a snake. This is a very original kind of structure,” Ye said.

The wiggles were the atoms strongly bonding to each other in pairs to form DNA-like helical chains, then stacking through weak forces called van der Waals interactions to form a tellurium crystal.

These van der Waals interactions set apart tellurium as a more effective material for single atomic chains or one-dimensional nanowires compared with others because it’s easier to fit into a nanotube, Ye said.

Because the opening of a nanotube cannot be any smaller than the size of an atom, tellurium helices of atoms could achieve smaller nanowires and, therefore, smaller transistors.

The researchers successfully built a transistor with a tellurium nanowire encapsulated in a boron nitride nanotube. A high-quality boron nitride nanotube effectively insulates tellurium, making it possible to build a transistor.

“Next, the researchers will optimize the device to further improve its performance, and demonstrate a highly efficient functional electronic circuit using these tiny transistors, potentially through collaboration with ARL researchers,” Qiu said.

In addition to the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation, Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency partly funded the work.

By U.S. Army CCDC Army Research Laboratory Public Affairs