Kansas tried to kill me once. It happened like this; a.k.a., this ain’t no bullshit. I returned from a three-year plus tour in Germany in the fall of 1978. I spent a couple of weeks leave with my parents and siblings in Kentucky and then drove cross-country to my new assignment at Fort Lewis, Washington. I had been a Sergeant, E-5 for almost two years and had managed to save a little money. I took that cash and bought a used Ford Pinto. For those of you too young to remember, the Pinto was one of the earliest American compact cars. It was supposedly prone to exploding into a ball of fire if rear-ended by another vehicle. I had no such experience. However, the Pinto was cheap and good enough for my needs. It served me well for the next year. This particular Pinto had two idiosyncrasies that are relevant to this story; the AM/FM radio never worked and the heater was anemic.

There were no GPSs in those days. I planned my trip by using a big Rand McNally booklet of roadmaps. I simply looked for the shortest route. That took me along Interstate 90 that generally parallels the northern border of the country. It was already early November, but frankly, I did not give due consideration to the weather. In my defense, there was no Weather Channel or weather apps in those days so a cross-country forecast was not available. I was in luck this time. There was quite a bit of snow on the ground in the northernmost states, but the roads were clear and I made good time. However, I did freeze my rear end off along the way. Therefore, when I took leave the next October, I traveled a slightly longer and more southerly route back home along Interstate 80. 80 runs through Nebraska and Iowa. The weather cooperated but the ride was still chilly. Consequently, I planned my return route even further south along Interstate 70, which runs through Kansas and the middle of the country.

I still had no clue what the weather would be enroute. By the time I got to Kansas City, it was around 2300 hours and a cold rain was falling. The temperature was already less than 40 degrees. I filled my gas tank and headed west, fully expecting to push through the rain in short order. I could not have been more wrong. Even before I got to Lawrence, Kansas – some 25 miles away – it was snowing heavily. However, the snow was “dry” and blowing in the wind rather than wet and heavy. I saw that as a positive since it was not freezing or packing on the road and the Pinto still had good traction. I continued to think that this was a linear storm that I would soon pass through and so I pushed on. Another 25 miles or so and I was just west of Topeka, Kansas. The going had been slow but steady. I had drafted behind an 18 Wheeler almost all the way; however, he turned into a Stuckey’s Truck Stop on the edge of town. I kept going…for approximately another 6 miles.

The snow had stopped falling by that point, but when the wind would gust, blowing snow caused brief whiteout conditions; there were no more tracks from other vehicles to follow and the road was becoming harder and harder to discern. I was probably going 5 miles per hour when I lost the road on my left side. I felt the difference when the Pinto left the pavement and immediately began to slide down the low embankment sideways, but I could not stop it. It was a truly slow-motion event as the Pinto snowplowed sidelong into a big powdery drift and came to rest only about 6 feet from the road. To make matters worse, the engine died and the headlights went out immediately. The car was canted slightly to the left and I knew that the driver’s side door was blocked by snow so I went out by the passenger door to survey the situation. I had been chilly in the car, but as soon as I stepped outside, I knew I was in deep trouble. It was bitterly COLD. I found out later that at the time, the temperature in Topeka was 12 below zero and the wind chill made it ~25 below. I was not prepared for that extreme in any way, shape, or form.

I had no flashlight, but the sky was now clear and there was some moonlight for illumination. I did a quick 360 but did not see any lights anywhere. I knew about how far it was back to the truck stop but had no idea if anything was closer in the other direction. There did not seem to be any farmhouses nearby and the closest line of trees appeared to be 100 meters away or more. That scan only took a few seconds but my toes, fingers, and ears were already burning and breathing the frigid air was hurting my nose and throat. I popped the hood and saw that snow had been pushed up around the fan blade and battery, melted by the engine’s heat, and refrozen almost instantly into a solid block of ice. I was not going to be able to do anything about that. I tried to close the hood, but it was frozen open. I jumped back into the car and could not fully close the passenger door because the latch had frozen. Likewise, moisture had heavily frosted over the interior of all the windows in the vehicle.

It was dark and cold in there, but at least I was out of the wind. I was wearing jeans, a t-shirt, loafers, and a light jacket – the standard fall uniform of young men in the 70s. I did not have a hat or gloves or heavier clothing with me. I dug into my duffle bag and wrapped another t-shirt around my head and ears. Through a combination of ignorance and hubris, I had managed to drive myself into a real-world life-threatening survival situation. At that point professionally, I had not gone to a formal survival course; however, I did have a modicum of training, skills, and experience. After three winters in Germany and a year at rainy Fort Lewis, I knew a lot about recognizing and mitigating hyperthermia and frostbite. As I sat there shivering uncontrollably in the dark I knew I had to act fast or risk succumbing in short order to one or both.

The Pathfinder Detachment I had been a part of in Germany belonged to the Division’s Aviation Battalion. We were issued all the same survival gear that the pilots and crew chiefs received. We also had the additional tasker to provide quarterly fieldcraft and survival refresher training to the aviators – principally to make sure they remained current on the issued items. Therefore, once a quarter for two years, I had been giving classes on things like shelter making and fire starting. For the most part, my teammates and I had taught ourselves those skills by reading the survival manual, following the instructions, and independently practicing the techniques. Then the detachment would go off to the local training area by itself. We would each give our assigned presentations to be “murder boarded” by the team before giving the classes to the aviators. A time tested old-school training methodology that worked well throughout my entire career.

That night in Kansas, I realized that I had been guilty of thinking about survival situations only in the context of a military mission gone wrong – soldiers cut off behind enemy lines and that sort of thing. Again, in my defense, the survival manuals I had read were almost exclusively focused on that potential circumstance. Likewise, those classes in Germany had been tailored entirely toward that kind of specific scenario. I was smart enough to know that I was woefully unprepared to unexpectedly be fighting for my life in Kansas. I was shivering too hard to dwell on it, and my ears, toes, and fingers were still hurting. I needed to get my blood flowing and core temperature up. A Pinto was never designed to be a gym. However, I began to do calisthenics as vigorously as I could in the cramped space. It would have made a hilarious video if someone had filmed it but I took it seriously and tried to work up a sweat. I did not manage that, but the exercise did help. Indeed, I was grateful that my toes and fingers were still painful and had not gone numb.

I had also failed to bring much in the way of survival gear or even basic supplies. I had no water or food available. However, hunger and even dehydration were not of immediate concern. On the plus side, I was young; physically fit, uninjured, and was certainly not lost. I knew exactly where I was and I was only feet away from a major thoroughfare. While the snow in the drift I was stuck in was perhaps three feet deep, the snow on the road was only about four inches and hardly impassable. Had my car been working and on the pavement, I would have likely been able to drive the Pinto out. Indeed, had I been wearing the appropriate cold-weather clothing, I could have reasonably considered walking out. By this time it was probably 0300 hours and I was beginning to wonder why no other vehicles had passed going in either direction. Had I missed them somehow?

What I did not know is that this severe early winter storm had been declared a statewide emergency and the Governor had closed all the roads. This was the heyday of the CB radio but I did not have one of those either. However, I suspect that the trucker who had pulled off the road got word of that shutdown on his CB. Although I did not know the reason, it became obvious that I was on my own – at least in the short term. I realized that a car with the hood up on the side of the road would appear abandoned and might not be searched or even approached. I started to think about drawing attention. I did have a couple of items to work with. I had a 4” Buck folder on my belt and a zippo lighter in my pocket. To be honest, I carried the Buck because that was what infantry soldiers did – on and off duty – to ensure that we were not mistaken for support soldiers. Likewise, while I did not smoke myself, I carried the lighter solely because – occasionally – a young lady needed a light for her cigarette.

At least I had some minimal tools to work with. I decided that as soon as there was some light I would throw out my spare tire, use my Rand McNally as tinder and perhaps throw on other clothing items if necessary to keep the fire going until the rubber started to burn. I did hope to get some heat from the fire but primarily wanted it to be a smoke pot. Indeed, I was concerned that it not be too close to the vehicle so that the fumes would be suffocating or smoke me out of the car. I decided to cut the stem and punch some additional holes in it with the knife to make sure it was completely deflated to avoid the possibility of it popping explosively when it started to burn. I was letting the air out of the tire when my plan became moot. Help had arrived and I had not seen or heard it coming. There was a pounding at the back of the car. I did not waste the opportunity. I kicked open the passenger door and surprised the Kansas State Trooper at the back of the car. He had been knocking the snow off the tag to get the license number of just one more abandoned vehicle.

I do not remember what we said to each other, but I grabbed my duffle bag and a minute later was in his very well heated Ford Bronco enroute back to the Stuckey’s I had passed some 4 hours earlier. It seemed a lot longer than that. In hindsight, there is some irony in the fact that I rode in on a Pinto and out on a Bronco. I had survived. The Pinto did not make it. That experience had a significant impact on me personally and professionally. It was sobering and left me with the conviction to never again be caught by an emergency so poorly prepared. I redoubled my efforts to learn traditional survival skills as well as other foundational life skills –like cooking – that have served me well.

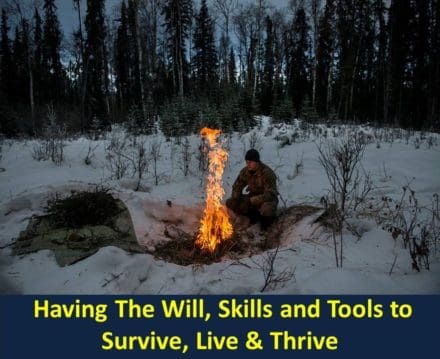

I did not have unlimited funds, but over time I equipped every vehicle I have owned since with essential tools for recovery and safety. Items like a machete and etool to dig or cut my way out if stuck; road flares to serve as a signal of distress as well as a fire starter; long-burning candles for warmth and light; two poncho liners per vehicle; gloves and wool hats, etc. In part, because I learned those lessons and made those preparations, I was never in such a dire situation again. I doubt I ever will be. The experience confirmed to me the things that the survival manuals talk about. In order to survive a person needs the will, the tools, and the skills – indomitable will being by far the most important factor.

I admit it was grim that night in Kansas, but I never stopped believing in my ability to ultimately prevail. However, it should be obvious, that had I been better prepared and informed I could have changed my route and avoided the storm and drama. Then it would have been just another boring and unremarkable cross-country drive rather than a dangerous adventure. Learning enough to avoid unnecessary risks is both a survival and life skill that is more common in older rather than younger people. It is definitely something that deserves to be passed from generation to generation. Some people, units, and leaders do not want to “waste” time learning “primitive” skills. First, it is misleading to think of these skills as primitive; thus implying that they are easy for modern people to master. On the contrary, successful fire starting, for example, is a complex enterprise that requires considerable practice.

I have observed that the will to live is strengthened considerably when individuals and teams have confidence in their capabilities. Therefore, to me, “survival training” of any kind – drown proofing for instance – is well worth the cost of time and resources. That is true even if the individual soldier never has cause to use those lifesaving skills in an actual emergency. Consequently, I strongly recommend leaders break out the manuals or find in house subject matter experts. Take your Messkit Repair Company (Airborne) out to the local training area, build some shelters, and start some fires. Bring in some chickens or bunnies and have a kill class, and – of course – eat your training aids. Do more than that. As leaders, we are responsible not only to teach our soldiers how to survive, or simply live in the field on the margins. We are teaching them how to individually and collectively thrive in the pervasively dangerous conditions of combat. Sure, trying to avoid death is job one. Nevertheless, that is just the minimum starting point. Nor should we ever go into battle with the goal of just “getting by” or fighting to a draw. A good unit prepares and fights to win – each and every day.

I have tried to consistently apply the survive, live, and thrive methodology to my life since that night in Kansas. In the interim, my wife and I have experienced two hurricanes, multiple tornadoes, a nasty ice storm, and even a relatively close encounter with a volcanic eruption when Mount Saint Helens exploded. We gained valuable experience from each event. We learned that it was infinitely better to be prepared rather than reactive. I am not a “prepper” as the term is perhaps unfairly, but still commonly applied. Nor do I consider preparedness a “lifestyle” choice or side-hustle. Preparedness is an integral part of my family’s life. It is our routine to keep a full pantry of nonperishable items. Therefore, we do not need to go out and panic buy when a crisis approaches. We keep our vehicles well maintained and habitually top them off if they get below three-quarters of a tank. Having learned multiple times that gas stations may not be able to pump gas out of their tanks if the electricity is off.

Many of those habits are traditional Army SOPs constantly reinforced by training and deployments. At the end of a mission, we automatically rearm, refit, and maintain our gear and vehicles before resting. The more self-reliant we can be individually the more resilient our military teams and civilian communities will be in a disaster – and the quicker we can bounce back from a setback. We have all seen it countless times. Shortly after the tornado passes, self-reliant people are out with their chainsaws clearing trees from their neighbors’ yards. We expect it. Ideally, being self-reliant makes us more selfless not self-centered. I caught part of the Tom Hanks movie “Cast Away” earlier tonight; specifically, the scene where he loses Wilson at sea. I was reminded that the Hanks character was only in a “survival situation” during the first 8-10 days on the island. Once he figured out fire, shelter, and food, he transitioned to living under austere circumstances. As I recall, he successfully lived that way for 4 years before loneliness drove him to build a raft and risk death again. He was living but not thriving.

All the successful people I know have made a habit of getting the most use out of their time. Many of us are in some form of isolation today. Awhile back, Gunz mentioned that it is a great time to start or restart a PT program. I agree. I have personally made a point of trying to learn new skills, read a good book, or build something. I refuse to binge-watch some TV show to waste time. In other words, I suggest investing time vice killing it. We are all facing a situation that requires us to live under more austere circumstances then we have been accustomed to. We learned to survive by changing our routines and embracing new habits like “social distancing.” Each region of the country may be in a different place in the continuum. However, like Hank’s character, many of us are through the survival phase and have largely adapted to the new pattern of our lives. I would suggest that all of us keep supporting those most at risk and on the front lines. Have confidence. Eventually, we will overcome this threat. In the meantime, we need to find ways to thrive and win. We are in this together.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.