I know this has nothing to do with diving, but I grow up outside of Boston, and I have always felt that this is an excellent piece of history. I am sure many of you have heard this story, but maybe you didn’t know all of it as you should.

On 5th March 1770, British troops in Boston killed five colonists. The incident was stared over a wig that lead to the taunting of British soldiers in Boston. The British retaliated by firing their muskets at the Americans, killing three and injuring eleven. Two of the injured succumbed to their injuries. The colonists’ deaths, which became known as the Boston Massacre, inflamed American anti-British feelings and was one of the most critical incidents leading up to the Revolutionary War.

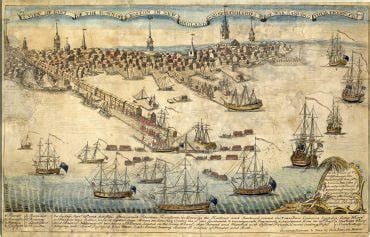

It was only a matter of time before the British troops sent to Boston clashed with the colonists. (General Thomas Gage had ordered over 4 British Army regiments to Boston, of which the first regiment landed at Boston on 1st October 1768. Two left in 1769) On 5th March 1770, the day arrived. A British sentry was stationed at the Customs House on King Street that early evening (today “State Street” in downtown Boston.) The colonists started taunting the sentry. The crowd grew quickly. Captain Thomas Preston, the Officer of the Day, ordered seven or eight soldiers under his command to assist the sentry as the crowd rose. Preston was not far behind. The crowd had increased to between 300 and 400 hundred men by the time the additional troops arrived. The British soldiers, whose muskets were loaded, were taunted by an ever-increasing crowd. The crowd then started throwing snowballs at the sentinels. One of the soldiers was knocked out by a colonist. As he stood up, the soldier fired his musket and shouted, “Damn you, shoot!” After a brief pause, British soldiers opened fire on the colonists. Three Americans died instantly: ropemaker Samuel Gray, mariner James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, an African American sailor. A ricocheting musket ball hit Samuel Maverick in the back of the crowd, and he died a few hours later in the early morning the next day. Patrick Carr, a thirty-year-old Irish refugee, died two weeks later.

The incident was soon called “the Boston Massacre.” But also known as the “Incident on King Street.” This alternate name is more popular among the British people. The depiction of the above events rapidly spread across the colonies thanks to Boston engraver Paul Revere, who copied a drawing by Henry Pelham. The image inflamed Americans’ distrust of the British. Captain Preston and four of his men were charged with manslaughter and convicted. The soldiers were tried in open court, with one of the Defense Attorneys being John Adams. Preston was found “not guilty” when it became apparent that he did not give the firing order. Some accounts say that the order to fire came from the crowd. The other soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter and had their thumbs branded as a punishment.

What lead to it

All the clashes between soldiers and civilians were published in the “Journal of Occurrences,” which was nothing, but a series of newspaper articles published anonymously. The Journal was aimed at chronicling the clashes between British soldiers and Bostonians, but in doing so, the reports were often exaggerated. These exaggerated reports led to further tensions. Unfortunately, the tensions between the civilians and the soldiers increased significantly after the death of Christopher Seider. He was an 11-year-old, killed on 22nd February 1770 by a British customs employee.

His death raised the tensions between the Britain troops and the civilians of Boston. Seider received the most prominent funeral in Boston, and the Boston Gazette covered the whole event. Media coverage continued and kept the tensions alive. Colonists started harassing soldiers, and the soldiers, in turn, started looking for a confrontation. A young man named Edward Garrick (who was an apprentice of a wig maker) showed up in front of the Boston Custom House and called out to Captain-Lieutenant John Goldfinch.Edward started saying that Goldfinch did not settle a bill from Garrick’s master. (He had paid for the wig the day before). Private Hugh White shouted at Garrick (as privates do) and asked him to be more respectful towards the officers. As the two-man started to yell at each other even louder, this began to make things worse. Garrick began to poke the Private in the chest with his finger. Private White responded by relinquishing his post and striking Garrick on the side of the head with the butt of his musket. Now the crowd started to get bigger. Both sides made threats. Henry Knox, who later became a general in the American Revolutionary War and Ft Knox fame, told the Private that if he fired, he should die for it. As, the evening progressed, the number of people in attendance grew. The church bells were rung. Many people came out because the bells signaled a fire. Private Hugh White, who had taken a safer spot-on Boston Custom House’s steps, was being surrounded by nearly 50 civilians. Crispus Attucks was one of the people in the crowd. He was a former slave who was of mixed race. Private Hugh White was forced to call for help due to the tumultuous crowd. Runners told Captain Thomas Preston, the officer of the watch, about the entire incident. Preston dispatched six privates and a non-commissioned officer from the Regiment of Foot as soon as he received the news. These soldiers were armed with fixed bayonet muskets. Preston had directed them to relieve Private Hugh. Captain Preston accompanied the six privates and the non-commissioned officer on the mission. To get to Private Hugh White, these eight people forced their way through the crowd. When they were approaching Private White, Henry Knox threatened Preston that if he shot, he would die. Preston replied to the alert by saying, “I am aware of it.” When Preston and his men arrived at Private Hugh’s place, the soldiers formed a semi-circular defensive position. They drew their muskets and pointed them at the onlookers. Preston then yelled at the crowd, telling them to disperse. The crowd was estimated to be between 300 and 400 people. Preston’s pleas were ignored, and the crowd began to move forward, tossing small objects and snowballs at the troops. Private Hugh Montgomery was struck by one of the items hurled by the crowd (one of the six privates who came to rescue Private Hugh). Private Montgomery was knocked down and lost his musket as a result of things being thrown at him. Private Montgomery recovered quickly, collected his weapon, and yelled angrily, “Damn you, shoot!” before firing into the crowd. There was a brief period of silence after Private Montgomery fired the shot, ranging from a few seconds to two minutes. After that, the soldiers opened fire on the crowd. Even though Captain Preston had not given any orders to shoot, the soldiers did so anyway.

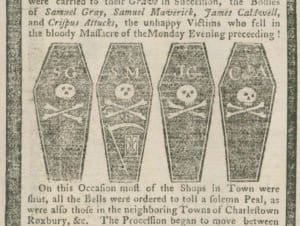

The bullets struck 11 people in the crowd. Private Montgomery was the soldier who assassinated Crispus Attucks. Samuel Gray was shot and killed by Private Kilroy, a soldier. Although all of the soldiers (including Preston) were arrested the next morning, and they all pleaded not guilty. A town meeting was held at Boston’s Faneuil Hall as Hutchison conducted his investigation. The Bostonians formed a committee to look into the incident. Samuel Adams was the chairman of the committee. The committee looked into it and recommended that troops be removed from Boston. During the initial investigation, four civilians were arrested for taking part in the massacre, but they were later found not guilty and released. The British administrators were forced to transfer the troops to Castle William, an old fort on Boston Harbor, under duress. For the events of 5th March 1770, Samuel Adams coined the word “Boston Massacre.” On 27th November 1770, Captain Thomas Preston and his eight men (including Private White) were brought to trial. Preston was tried separately from the other soldiers. Josiah Quincy Jr. and John Adams were the trial’s defenders. Samuel Adams, the chairman of the Bostonians’ committee, and John Adams’ nephew. Samuel Quincy and Robert Treat Paine were the trial’s attorneys. At the appeal, Captain Thomas Preston was found not guilty on all charges, and he returned to England on 2nd December 1770. For all of the hardships he suffered during the Boston Massacre, he got a £200 reward. Two of the eight soldiers were convicted of manslaughter. Kilroy and Montgomery were sentenced on 14th December 1770, nine days after their trial. They were expected to face the death penalty as a matter of course. Montgomery and Kilroy both filed appellees, and their lives were spared. They were released, but the letter “M” was tattooed on their thumbs, indicating manslaughter. On 8th March, the first three victims of the Boston Massacre were buried at the Granary Burying Ground. On 17th March, the fourth individual to die was buried alongside the first three. The victims’ funeral procession drew 12,000 people from Boston. The procession also paid a visit to the Liberty Tree.

It was your John Adams (future Founding Father & POTUS) that defended the troops & cut through much of the propaganda being circulated on the event.

Yes i said that. It was called the trial defender today’s defense attorney. Thanks

great story. good to be reminded of it. thanks.

The term Americans is used in the article, there were no Americans at the time everyone was a British subject so it was British soldiers killing British civilians.

Yes, they were British subjects. But they were also Americans.

“English use of the term American for people of European descent dates to the 17th century, with the earliest recorded appearance being in Thomas Gage’s The English-American: A New Survey of the West Indies in 1648. In English, American came to be applied especially to people in British America and thus its use as a demonym for the United States derives by extension.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demonyms_for_the_United_States#Development_of_the_term_American

Tom,

They were called Americans and also colonists. Also when i write about Paul Revere i will make sure he yells the regulars are coming not the British as we were all brits.