In 1982, Gen. Galtieri’s Argentine military regime faced increased domestic trouble at home and they were looking to hold on to power. Since the formation of the Argentine state, the Malvinas issue (Basically the Sovereignty over the Falkland Islands between Argentina and the United Kingdom) had created political and domestic passions and heated debate in Argentina. It was the ideal moment for Galtieri to reclaim what Buenos Aires called the “lost islands”. Negotiations with the British over sovereignty had been going on for many years, with various British governments being more sympathetic than others to the proposal. Long-standing tensions between the two countries reached a head on March 19, 1982, when some Argentinian scrap metal workers lifted their country’s flag at an abandoned whaling station on the even-further-away island of South Georgia, which was then a Dependency of the Falkland Islands. Two weeks later, on April 2, Argentinian troops stormed South Georgia’s Leith Harbor, overwhelming main British outposts without causing any casualties. But after conquering the islands, Galtieri and the junta regime faced one big problem: Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher’s Conservative government, which was dealing with increasing unemployment, rising interest rates, and an ailing economy, was also facing a degree of domestic hostility. The Argentine invasion of British sovereign territory was intolerable to Thatcher and much of the world and had to be dealt with. There were no contingency measures for the Falklands at the government level or within the military, let alone possessing the mechanisms to launch a task force to fly the 7,000 miles to the islands. Despite efforts to secure a diplomatic solution at the United Nations and through the Reagan administration, the two parties were stubborn and war appeared inevitable.

Lt. Col. Mike Rose, commanding officer of 22nd Special Air Service Regiment in Hereford, was on the phone to the headquarters of the British Antarctic Survey Group in Cambridge during the afternoon of Friday, 02 April 1982. Having learned that Argentine forces had invaded the Falklands, Rose swung into action and called in the regiment’s top advisors, canceled leave, and created a command situation. The situation was a difficult one for SAS planners. In the case of the invasion, no contingency arrangements were in place to rehabilitate the Falklands. This possibly owed more to the Ministry of Defence’s general disbelief that an operation to recover the Falklands was feasible. The tiny British settlement of the Ascension Islands, about 3,700 miles from the UK and halfway between the Royal Navy’s ports and the Falklands themselves, was the only practical ‘jump off’ point for the Falklands.

In Hereford, events started to move fast. Keen (had to use a British word) to play a pivotal role for his men in the upcoming operation, Rose provided SBS (Special Boat Service) with the services of two specialist Boat Squadron men who were preparing to sail to the South Atlantic. Rose was closely aligned with Brigadier Julian Thompson OBE, who commanded a landing on the islands for the operation code-named “Corporate”. An advance group from “D” Squadron SAS joined their SBS comrades on Sunday, 04 April and flew to the Ascension Islands. The Falklands Task Force was commanded by Rear Adm. Sandy Woodward on his flagship HMS Hermes, specially approved by the British Cabinet. The Battle Command Headquarters, Operation Corporate’s command center, was also located onboard Hermes. In an attack on the island of South Georgia, about 900 miles south of the Falklands, the men of D Squadron SAS’s mission were to join 42 Royal Marine Command.

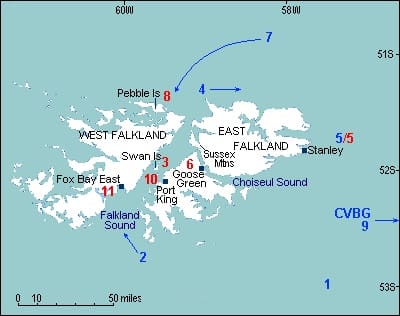

San Carlos Bay beaches on East Falkland offered the best hope of a British landing for Task Force Commander Woodward. On the opposite side of the island from Port Stanley, before the long march across the island to seize Stanley, the Brits needed to establish a bridgehead. The problem for Woodward was that, to the west of the San Carlos beaches, the Argentinians had built a forward airbase on Pebble Island. The threat needed to be neutralized, with a garrison of over 100 men armed with ground attack IA-58 Pucaras, each with two 20 mm cannons and four 7.62 machine-guns. D Squadron’s boat troop men, fresh from South Georgia operations, were assigned to recce on Pebble Island. On the night of Tuesday, 11 May, the reconnaissance party’s forward frame edged its way to the narrow one-mile strip of land bordered by the sea on either side and offered no natural cover. The D Squadron men had to travel with extreme care and were forced to leave their Bergen backpacks in a shallow hollow to avoid detection against the horizon. However, the Argentinian sentries were not especially alert. The rest of Woodward’s landing fleet gathered before beachhead landings at San Carlos as the recce party confirmed Hermes’ findings.

G Squadron Assault (Mountain Troop)

The timeline was tight for the attack on Pebble Island. The assignment was given to Capt. John (Gavin) Hamilton, a young 29-year-old Mountain Troop Leader. Hamilton and his men had already survived two helicopter crashes in Fortuna Glacier’s blizzard conditions in the thick of the South Georgia action. Still, he led his men to seize the outpost of Grytviken, the former whaling station. He was under no illusion as to the scope of the mission and the dangers involved as he briefed the Mountain Troops’ men.

Onboard HMS Hermes, Hamilton briefed his men, but there were some problems. As the Hermes faced the South Atlantic’s heavy headwinds, she was well behind schedule, and she arrived late at the launch site. The foul weather had stopped the Sea King helicopters from being set up on the flight deck as they steamed west to make things worse. With the legendary SAS versatility, Hamilton was forced to revise the attack plan and change the production to take 30 minutes instead of the initial 90. With the men of the Mountain Troops armed with 81 mm mortars, M203 grenade launchers, and the deadly Rule 66 mm anti-tank rockets, the Sea King left Hermes’ deck. In support, to take out the Argentinean garrison positions, a Naval gunnery officer landing with the SAS said he would help provide the Naval Gunfire Support (NGFS) directing the fire from the decks of HMS Glamorgan of their 4.5-inch guns. The Sea King touched down four miles from the airstrip at a point marked out by the Boat Troop in reasonably calm weather. As troops from the Boat Squadron established a defensive perimeter, Hamilton and his men emerged from the Helo and started to unload mortar bombs and light guns. The Mountain Troopers were instantly hit by the unbelievable moonlight and the silhouette problems against the solid landscape began. The SAS men humped their way across Pebble Island to the airstrip after a short briefing from the Boat Troop (G Squadron) commander.

The outline of the FMA IA 58 Pucará (an Argentine ground-attack and counterinsurgency) (COIN) came clearly into place as they approached the airstrip, as rounds from the guns of HMS Glamorgan started crashing into the Argentinian garrison. Hamilton assembled his men on aircraft dispersals and calmly affixed explosive charges to the waiting Argentinian jets, receiving inaccurate incoming small arms and machine gunfire. The shells from Glamorgan destroyed the Argentinian fuel dump, ammunition store, and watchtower as the first of the Pucaras were blown up, producing some secondary explosions, and illuminating the remaining Pucaras further. The SAS men took out 11 planes, including six Pucaras, four Turbo-Mentors, and a Skyvan transport aircraft, in a 20-minute frenzy of destruction. Between them, in glaring view of the enemy, Hamilton and ‘Paddy’ Armstrong, a Mountain Troop explosives specialist, had destroyed another four Pucaras.

Withdrawal and Assessment

The whole operation was running on time. Within 30 minutes, the SAS had neutralized the Argentinian outpost and all the aircraft. There were minor casualties; one man was struck by shrapnel, and one was concussed from a remote-controlled Argentine mine. The entire SAS force was picked up by the Sea Kings on a tight schedule and transported back to HMS Hermes and Glamorgan, where a well-earned, full-cooked English breakfast awaited! Hamilton confirmed, de-briefly, that the Argentinians had not put on the island a radar facility and that the garrison was made ineffective. As a result, the Argentine force on Pebble Island played no part in opposing the landings in San Carlos, and again the SAS supported the main landing force that had famously crossed East Falkland to free Port Stanley.

On 10 June 1982, while directing naval gunfire from a position overlooking an 800-strong Argentinian garrison, Capt. John Hamilton was tragically killed. Hamilton, surrounded, was killed while covering a soldier who slipped through Argentina’s lines and was finally taken prisoner. The Military Cross was posthumously awarded to Hamilton and the award’s quote cited his “outstanding determination and character, his extraordinary will to fight despite hopeless odds and wounded suffering”. Only four days later, Maj. Gen. Jeremy Moore accepted the surrender of the islands’ Argentine forces, and the Union Jack was returned to the Falklands.