FORT LIBERTY, N.C. — Team members with the U.S. Army Medical Materiel Development Activity joined dozens of U.S. Army medics at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, to assess the progress of several traumatic brain injury detection devices as part of a Soldier touchpoint this week.

The Soldiers provided feedback on two brain trauma assessment devices currently under development at USAMMDA under the management of the Warfighter Readiness, Performance and Brain Health Project Management Office and stakeholders with the North Carolina Center for Optimizing Military Performance. The event, which included combat casualty assessment lanes inside Fort Liberty’s Iron Mike Conference Center, was designed to assess the progress of TBI Field Assessment Device program and inform future program development. Feedback from prospective end users — U.S. Army medics, medical officers, and combat troops — is a vital step in development programs, according to U.S. Army Lt. Col. Dana Bal, a product manager with WRPBH.

“These types of end-user interfaces are vital to what we do in the WRPBH PMO,” said Bal. “The information we gather — both from our own observations as advanced developers and from the critiques we get from the medics and medical officers actually using the device — is incredibly important to how we approach the development process. Our ultimate goal is to develop materiel solutions that meet the needs of the Warfighters, and we couldn’t do that without these types of opportunities.”

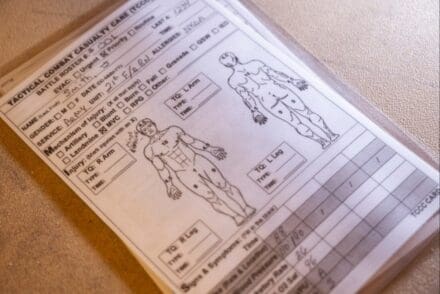

During the touchpoint, volunteer Soldiers from multiple units assigned to the U.S. Army’s largest base conducted TBI assessments on role player casualties to determine the effectiveness of the devices in a simulated real-world environment. The event was designed to gauge the effectiveness of the TBI assessment devices to detect possible brain trauma outside a clinical environment, like those found at U.S. Army role 1 and role 2 care facilities. The Soldiers provided feedback about the devices’ ease of use, design features and overall fitness for use in austere, remote environments.

“These development programs can last years, starting with identifying a capability gap or unmet treatment need, through design, modifications and FDA approval, and finally, fielding products to U.S. military medical providers and units, including through sustainment of these capabilities,” said Bal. “With the need for rugged, reliable, user-friendly devices to aid in assessing possible TBIs, we are focusing more and more on how to meet the current and future needs of military medical providers, and hearing feedback from subject matter experts helps refine our approach.”

Traumatic brain injuries, caused by exposure to concussive events like roadside bombs and indirect fire, are a significant threat to frontline service members. There have been more than 505,000 traumatic brain injuries reported within the Department of Defense since 2000, ranging from mild to severe. Many TBIs are not accompanied by exterior signs of injury yet can have both short and long-term health effects. In TBI cases, identifying internal injuries, like intercranial hemorrhage or other non-visible brain damage, is a vital first step to ensure injured are treated adequately across the continuum of care.

The WRPBH TBI assessment programs are designed to develop devices that are rugged, deployable, cost-effective and user-friendly in the hands of medical providers as close to the point-of-injury as possible. This allows the providers to shape treatment decisions before, during, and after medevac post-injury, according to U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Andrew Procter, senior enlisted advisor for USAMMDA’s Soldier Medical Devices PMO.

“TBIs can be very hard to recognize immediately after a concussive event because there usually no visible signs of injury,” said Procter, a medic with nearly 20 years of experience and multiple deployments across the globe. “Medics and first responders usually focus on outward signs of injury — bleeding, burns, airways, broken bones, things that are immediately apparent after injury — to stabilize a patient before medevac. Because determining the severity of TBIs requires specialized screenings and imaging devices, it’s tough to accurately diagnose the severity and type of brain injury in a field environment. But what we are doing now, what the WRPBH team is focusing on, will hopefully give future medics and first responders a way to recognize TBIs and assess their severity before evacuation decisions are even arranged.”

During recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, wounded service members were usually less than an hour from higher echelons of care due to the availability and proximity to the front lines of evacuation aircraft and vehicles. The “Golden Hour” roughly described the minutes immediately after a wound occurred and indicated the amount of time medical providers had to assess a casualty, stabilize them, and arrange for evacuation. But during future conflicts, with logistics and evacuation capabilities limited by distance and austerity found in regions like the Arctic and Indo-Pacific, the Golden Hour may not be a feasible amount of time to move injured and wounded to higher care facilities. To answer the TBI treatment challenges presented by possible future conflicts in remote locations, the USAMMDA team works each day to develop new capabilities and improve tested treatments to meet the needs of tomorrow’s Warfighters, said Procter.

“Our Joint Force medical providers have had a very robust logistics capability the past quarter century and our ability to save and preserve lives has been unmatched by any period in history. What we recognize, however, is that our current treatments for injuries are very much tied to our ability to move casualties rapidly from point-of-injury to more advanced facilities further from the front lines,” said Procter. “The TBI assessment programs we’re currently developing will hopefully go a long way to maximizing ground commanders’ evacuation options, limit unneeded evacuations, shorten the time from injury to the start of treatment, and help keep Warfighters in the fight.”

USAMMDA develops, delivers and fields critical drugs, vaccines, biologics, devices and medical support equipment to protect and preserve the lives of Warfighters across the globe. USAMMDA Project Managers guide the development of medical products for the U.S. Army Medical Department, other U.S. military services, the Joint Staff, the Defense Health Agency and the U.S. Special Operations community.

The process takes promising technology from the Department of Defense, industry, and academia to U.S. Forces, from the testing required for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval or licensing to fielding and sustainment of the finished product. USAMMDA Project Management Offices will transition to a Program Executive Office under the Defense Health Agency, Deputy Assistant Director for Acquisition and Sustainment.

By T. T. Parish