There were never more than fourteen at one time. They were licensed spies who were uniformed members of the United States military but who also held Soviet credentials or passes allowing nearly unrestricted access into and within the Soviet sector of East Germany. They were backed up by another 50 “off pass” personnel – drivers, equipment recognition specialists, analysts – all of whom were hand-picked experts in their fields. All were members of the US Military Liaison Mission (USMLM), a unique and elite joint service organization that was founded in 1947 and formalized in a bilateral agreement between the American and Soviet Chiefs of Staff. They answered only to the Commander-in-Chief, US Army Europe. The British and French had similar agreements – and the Soviets had liaison teams of their own, who patrolled throughout the Allied sectors of West Germany.

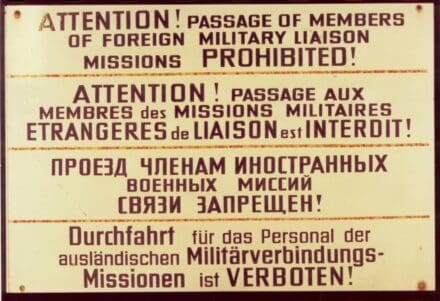

Mission Restricted Sign, in English, French, Russian, and German. These signs were nailed to seemingly every tree in East Germany, and consequently routinely ignored by the Allied Liaison Missions.

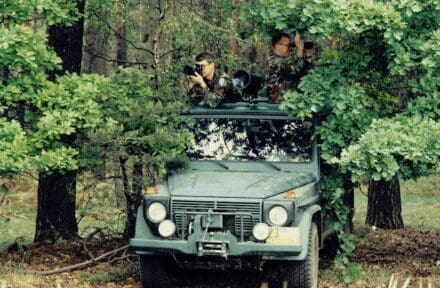

They traveled in teams (called tours) of two: an Army or Air Force officer who was a Russian linguist and Soviet specialist, paired with a noncommissioned officer driver who was fluent in German. They traveled in a standard four-wheel drive, non-descript vehicle, and were equipped with notebooks, binoculars, night vision goggles, tape recorders, cameras, compasses, maps, rations, and personal items, but no weapons. No espionage gear or other spy paraphernalia was ever carried. These “spies” never met with agents, conducted dead drops, intercepted messages, or participated in any clandestine activities. According to Major General Roland La Joie, a former commander of the USMLM, “the tours were really nothing more than overt mobile observation platforms crisscrossing the GDR [German Democratic Republic], seeking militarily useful information. The search, of course, was not entirely random.”

Potsdam House, the headquarters of the US Military Liaison Mission in East Germany.

Tours were assigned targets based on intelligence collection requirements from national and theater intelligence agencies. The targets included Soviet or East German garrisons, temporary deployment areas, field training areas, air-ground gunnery ranges, communications sites, river crossing areas, railroad sidings, and virtually anything else of military value in the country. Newly introduced or modified military equipment, especially combat vehicles and aircraft were always at the top of the target list. By virtue of the bilateral agreement, the only locations off-limits to the USMLM were “places of disposition of military units,” so the tours had to be exceedingly careful of where they stationed themselves to observe things such as military movements or tactical exercises. Tour members duly pursued, observed, recorded, and photographed whatever they encountered.

Members of the US Military Liaison Mission on a tour observing Soviet ground forces in East Germany.

The enemy’s capabilities were only part of the problem; the MLM was also tasked to look for indications of intent to use those capabilities. La Joie writes: “On every single day throughout the Cold War, eight or more Allied tours were roaming the countryside of East Germany. Every day, all night, each tour looking exactly for signs of imminence of hostilities.” Because of their unique and expansive access to Soviet military forces in Germany, the USMLM was included in all discussions about the Soviet threat, at both military and diplomatic levels. Their perspective from within the Soviet sector was exceptionally clear, even if incomplete.

Despite the official agreement, the Cold War had heated up over the decades, and the danger was genuine: On March 22, 1984, a member of the French Mission lost his life in a staged traffic “accident.” Almost exactly one year later, on March 24, 1985, Major Arthur D. Nicholson of the USMLM was shot and killed by a Soviet sentry while on a routine liaison mission. However, despite the dangers, the Missions persevered. Dutiful to the end, MLM members monitored the withdrawal of Soviet forces out of Germany and across the Polish border. They remained at their posts until the day the two sides of Germany were reunited, on October 3, 1990, at which time the Military Liaison Mission declared: Mission Accomplished.

By Ruth Quinn, Staff Historian, USAICoE Command History Office

Interesting that the Frenchmen can be acknowledged as a traffic accident, but not General Patton’s “accident” by the court historians and those that carry water for the court.