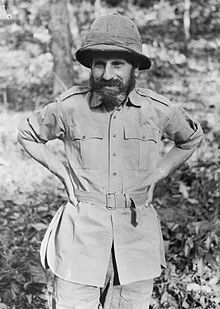

Major General Orde Wingate has memorials in England, Israel, and Ethiopia. Though he was unorthodox, erratic, and difficult to work with, many admired his eccentricities. Wingate, who ate raw onions for their health benefits and who cleaned himself with a hairbrush of sorts, also believed, quite openly, in his superiority. This, along with his sometimes-disheveled looks and foul body odor, alienated more than a few of his commanders and colleagues. He was also known for being in his tent completely naked and running staff briefings. The most well-known of his contributions is his creation of the Chindits battalions for deep-penetration missions into the Burmese jungles behind Japanese lines. The missions’ effectiveness is a matter of debate, but Wingate’s exploits have secured him a place as a legend, if a very odd one. Wingate was born on February 26, 1903, in India to a British army officer. He had six siblings, so they were with him for most of his childhood. The family moved to England before 1916, and Wingate attended formal education in England.

In 1921, he was accepted to Woolwich Military Academy, where he studied infantry and artillery tactics. He was known to be rude, obstinate, and intolerant. He excelled in horseback riding at the Military School of Equitation. Because of this skill, he was promoted to the cavalry. Throughout his early career, Wingate always tested people. It was often because he rubbed people up the wrong way and didn’t conform to the “old boys’ network” that the officer class of the British Army consisted of in those days. In 1928, he was sent to Sudan to keep an eye on possible uprisings against British colonial rule and map it. Wingate traveled to Sudan by bicycle and then took a boat from Yugoslavia to Cairo, Egypt. He reached Khartoum and was eventually transferred to the Sudanese Defense Force. Most officers would’ve considered this a black mark on their career, but he thrived in Sudan and the harsh environment, considering it a challenge and a way to “toughen up.” He served in the East Arab Army and commanded units patrolling Ethiopia’s border, preventing the trade in black slaves and ivory. He enjoyed being out on the trail. He was unpopular with other officers due to his abrasive personality.

Next, Wingate went to the British Mandate for Palestine (today’s Israel). There, he was decidedly pro-Jewish in a majority Arab country and in an army where many of the officers did not like the natives, either Arab or Jew. He proceeded to get involved in the Jewish communities, their leaders, and Zionist movements. Wingate believed that it was his religious obligation to support the creation of a Jewish state. He pushed the boundaries of his duties, and some say he exceeded them, helping militant Jewish groups with money, arms and intelligence. With the reluctant support of General Archibald Wavell, Wingate aided militant Jewish groups in attacks against Arab militants during the Arab uprisings of the late 1930s.

To fight the Palestinian Arab guerrilla forces in the area, Wingate suggested to Major General Archibald Wavell (commander of British troops in the area at the time) the idea of commando units of British and Jewish troops to counter raids, saboteur operations and find the villages where the guerrillas sought refuge. Wavell approved, and Wingate formed the Special Night Squads from volunteers in the British Army and Haganah, the Jewish paramilitary force that was the precursor to the Israeli Defense Force. For his actions in Palestine, Wingate was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and became a hero in the Jewish community. He is still remembered in Israel to this day for his huge role in training Haganah forces. After England was drawn into World War II, he was sent to Ethiopia to organize a guerrilla force around the Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie. The Italians had conquered the country of the latter in 1936-37. The “Gideon Force” was a group of irregular troops that shared Wingate’s vision for the irregular forces and fought with him in Palestine.

Like many “different” individuals throughout the history of military service, Wingate inspired either complete disdain or total loyalty, and most of his loyal followers followed him to Ethiopia and beyond. Gideon Force, made up of British, Ethiopian, and Sudanese soldiers, soon ran the Italians ragged, and in a war that they were ill-equipped to fight, forced the Italian forces of 2,000 men to surrender to their 20,000 in 1941. Emperor Haile Selassie was another man who admired Wingate and looked upon him favorably. In February 1941, Wingate created his new command. Requested by the new commander-in-chief of Middle East Command, Wavell, to fight the Italians in Ethiopia, Wingate traveled to Sudan and formed the Gideon Force. The Gideon Force was named after the biblical Judge who defeated a large army with a small army.

Wingate’s Gideon Force, numbering about 1,700, moved behind enemy lines and attacked supply lines while working with local militias to attack Italian forts. Operation Gideon Force was successful in the end, due to the surrender of 20,000 Italian troops. Wingate accompanied Emperor Haile Selassie on his return to Addis in May 1941. He was awarded his second unit citation for his exemplary service. In both Palestine and Ethiopia/Sudan, Wingate’s relationships with local communities and populations were seen by other officers as highly inappropriate. This, combined with his official reports in which he often railed against other officers and the higher command, hurt his chances at promotion and led to him being moved frequently.

Also, there was the issue of his eccentricity, which included wearing a wreath of raw onion and garlic around his neck, which he would frequently chew into and greet guests to his command tent while entirely naked. Wavell established an affinity for Wingate and his creativity, and when he became commander of the South East Asian Theatre, he helped Wingate secure a command. Reports of Ethiopia reached Winston Churchill, searching for innovative and creative ways to take the war to the enemy. This allowed him to get an audience with Churchill, who was impressed by the idea and asked that he come up with a plan. Wingate arrived in India in March of 1942 to become a colonel for the British shortly before India’s Japanese takeover. Wingate commanded the Indian 77th Infantry Brigade and trained them in the art of jungle warfare. With this training, he learned to camp in the jungle during the monsoon season, which led to hundreds of men getting sick. Wingate believed exercise and mental strength would boost one’s resistance to infection. However, his eccentricity directly led to poor managerial decision-making.

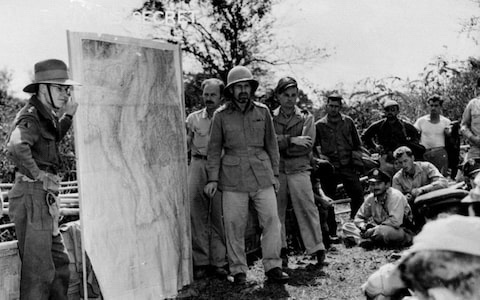

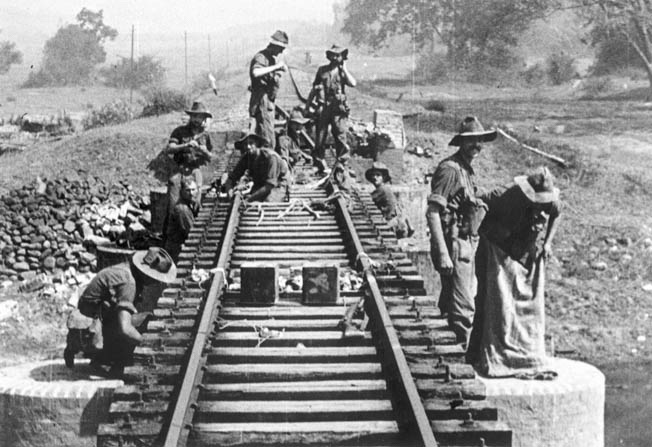

Wingate was ordered to form a group of guerrilla-style fighters to take the battle behind Japanese lines to disrupt communications, gain intelligence, and force the Japanese to divert troops that might be needed in more strategic areas. To create the “Chindits,” Wingate copied the Burmese word for a mythical, fearless lion. The first Chindit mission in February 1943 was a failure. The Chindits made trouble for the Japanese behind their lines in Burma, but poor logistics and underestimating how mobile the Japanese were forced the Chindits back to India in March. They had pushed too far into Japanese territory, and when they attempted to retreat, the Japanese surrounded them. Wingate split-off his men into smaller groups and arranged them to expedite their return. Through the war’s remainder, the Wingate Troop’s survivors trickled back to India. The loss of one-third of the men raised the morale of the other troops. They were encouraged by this, and it boosted confidence further. Wingate was given another opportunity to the situation.

Wingate was given overall command of six whole brigades and the mission. Two were dropped via gliders during World War II into Burma behind enemy lines in March. Those men cleared landing strips so other aircraft could land. Though many officers argued that the mission took the most battle-hardened troops away from the front line of battle, as the Japanese tried to push into India, they were constantly distracted by the Chindits, which delayed their advance. The Japanese attempted to isolate the small force, using three infantry divisions to chase a force of perhaps 8,000 men (the force increased in size to about 12,000 in 1944). In 1944, the Chindits penetrated deep into Burma and found strong points deep in the jungle, from which to strike out and harass the Japanese. This strategy was so successful that the Japanese decided to eliminate the threat from the Indian border. This resulted in significant battles at Imphal and Kohima, some of the most brutal fighting in that theater. Throughout the process, the Chindits harassed the Japanese column, weakening them for the decisive battles.

The Japanese commander, Mutaguchi Renya, said that he would have likely achieved a Japanese victory had he not been forced to put up a fight against the Chindits. Wingate’s force definitely contributed to Burma’s victory, even though their achievements may have been overstated. When his plane crashed on March 24, 1944, Major General Wingate was on his way to inspect his troops in the Burmese jungle. Three British officers, as well as the American pilots, died in the incident. Their remains were archived in India. Following their deceased relatives’ wishes, they were subsequently interred in the United States at Arlington National Cemetery. The Chindits continued under other commanders until the end of the war, using Wingate’s tactics, who is still considered one of the most innovative tactical strategists of the 20th century. Wingate is regarded for his unorthodox approaches to unconventional warfare and as a very unusual man. But he was also one of the best wartime leaders and innovators of WWII.

Good write up. Interesting element about the Kohima campaign was it included some of the few local pro-Japanese militias, among the indigenous people who sided with them to fight both British and Indian rule, and who REALLY fought a guerilla war – some still to this day. That region is still awash with independent groups fighting whoever tries to rule them.

There should be a statue of him at Bragg

There should just for the fact that he went to meeting naked! but there should be more said about him in the US

where would Reggae and Rastafarianism be without this giant?

Fascinating story… the Brits sure had some characters running unconventional operations in WWI and WWII.

Definitely a “Break Glass in time of War” Officer. Much disdained by British society, and not particularly well remembered in the big scheme of things. But, the right man at the right time.