For Frogman, the battle of Tarawa marks the birth of the UDT and the start of a very long history for Naval Special Warfare. Because the Higgins boats that were taking the Marines to shore got stuck on coral reefs, the Marines would have to jump out in some case far from shore. More Marines drowned or died in the water from enemy fire then killed in the next two days of fighting. So, the Navy came up with the Underwater Demolition Teams to recon landing sights to make sure the Marines could land.

But for the Marines, it was another day in an already long history. The Battle of Tarawa was fought on 20–23 November 1943. It took place at the Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, in the Pacific Theater of WW2 and was part of Operation Galvanic, the U.S. invasion of the Gilberts. Nearly 6,400 Japanese, Koreans (forced labor by the japenese), and Americans died in the fighting, mostly on and around the small island of Betio, in the extreme southwest of Tarawa Atoll. The U.S. had similar casualties in previous campaigns, like the six months of the Guadalcanal Campaign, but the losses on Tarawa happened in just 76 hours.

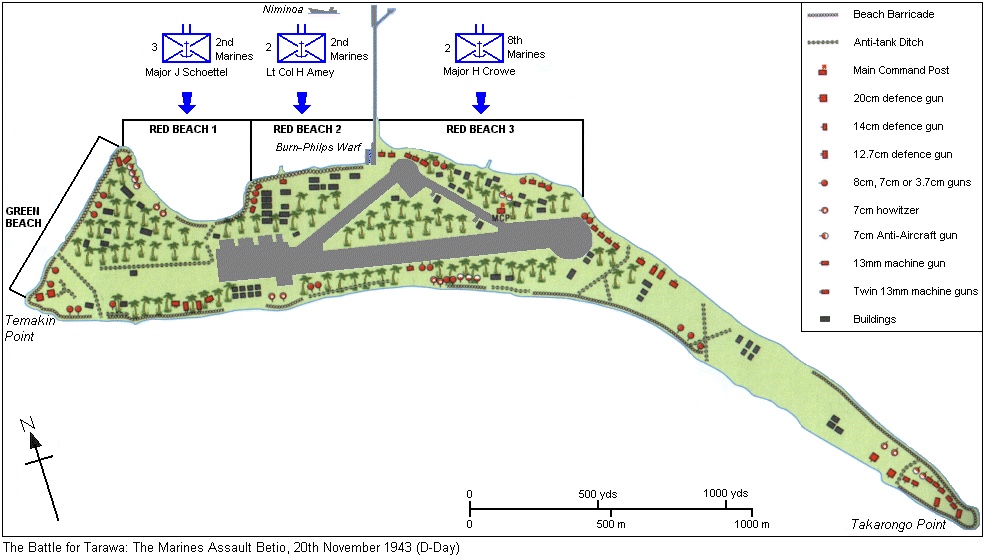

The Battle of Tarawa was the first American offensive in the critical central Pacific region. It was also the first time in the Pacific War that the United States had faced severe japanese opposition while conducting an amphibious landing. Previous landings met little or no initial resistance. As the Japanese strategy was to let them land and attack after they let their guard down. (but that didn’t work against the USMC). On Tarawa, the 4,500 Japanese defenders were well-supplied and well-prepared, and they fought almost to the last man, exacting a heavy toll. The Japanese said it would take the U.S. “one million men 100 years to take Tarawa.” That is saying a lot for a piece of land that was only 3 miles long and about 800m wide. The Japanese had fortified the island with about 500 pillboxes, four eight-inch gun turrets, and numerous artillery and machine-gun emplacements. A coral and log seawall ringed most of the island, and 13mm dual-purpose anti-boat/antiaircraft machine guns protected the beaches.

On the morning of November 20, following a naval bombardment, the first wave of Marines approached Betio’s northern shore in Higgins boats. The men encountered lower tides than expected and were forced to abandon their Higgins Boats on the reef that surrounded Betio and wade hundreds of yards to shore under intense enemy fire. When the Marines reached the Red beach, they struggled to move past the sea walls and establish a secure beachhead. By the end of the day, the Marines held the extreme western tip of the island, as well as a small beachhead in the center of the northern beach. In total, it amounted to less than a quarter of a mile.

There were immediate issues from the start. The naval gunfire stopped at 0900, while the Marines in their Landing Vehicles, Tracked (LVT), were still 4,000 yards offshore. Because of the lower-than-expected tide, the Higgins boats carrying later waves would not be able to make it over the reefs in the bay. As the Marines approached the shore, they realized the naval bombardment had been rather ineffective. They started taking heavy fire from the Japanese as they made their way across the lagoon.

Assault companies, K and L, suffered over 50 percent casualties in the first two hours of the assault. The following waves were in even more trouble. Embarked in Higgins Boats, they had no choice but to unload at the reef due to the low tide. They had to wade ashore over 500 yards under heavy fire.

This was how the men of L company under Major Mike Ryan made it ashore. Rather than leading his men directly into the carnage of Red Beach 1, Ryan followed a lone Marine he had seen breach the seawall at the edge of Red Beach 1 and Green Beach, the designated landing area that comprised the western end of the island. Ryan’s landing point caught the eye of other Marines coming ashore and they headed towards Ryan’s position.

As more Marines from successive waves and other survivors worked their way to the west end of the island, Ryan took command and began to form a composite battalion from the troops he had. These men would come to be known as “Ryan’s Orphans.”

On the beach, the Marines of 3/2 continued to fight for their lives. After managing to wrangle two anti-tank guns onto the beach, they realized they were too short to fire over the seawall. As japanese tanks approached their positions, cries went up to “lift them over!” Men raced to get the guns atop the seawall just in time for the gunners to drive off the Japanese tanks. Maj. Ryan’s Orphans and others had acquired a pair of Sherman tanks. Learning as they went, the Marines coordinated assaults on pillboxes with infantry and tank fire. This gave the Marines on Betio their most significant advance of the day as Ryan’s orphans were able to advance 500 meters inland.

3rd Battalion was severely mauled in the initial assault on Betio. Surrounded by strong Japanese fortifications, the survivors on Red Beach 1 would fight for their lives for the remainder of the battle. Ryan’s orphans made a significant contribution to the battle in opening up Green Beach, so men of the 6th Marine Regiment could come ashore to reinforce the battered survivors. Now reformed, 3/2 would take part in one of the final assaults to secure the island, helping to reduce the dedicated Japanese fortification at the confluence of Red Beaches 1 and 2.

By November 23, 1943, after 76 hours of fighting, the battle for Betio was over. More than 1,000 Marines and sailors had been killed, and nearly 2,300 were wounded. Of the roughly 4,800 Japanese defenders, about 97% were thought to have been killed. Only 146 prisoners were captured.

Maj Ryan was awarded a Navy Cross. Four Marines would be awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the battle — three of them posthumously.

The military learned vital lessons from the invasion of Tarawa. The organization of amphibious landings was changed, and by D-Day, they would be far more effective. The tactics techniques and procedures of using tanks and infantry together to fight a well-intrenched enemy and other lessons learned would be used for the rest of the war. To this day, the lesson learned on Tarawa is used as the base for all amphibious operations.

SCUBAPRO Sunday is a weekly feature focusing on maritime equipment, operations and history.

Gives me chills every time to read about Tarawa and try to imagine fighting there.

Semper Fidelis.

Research has proven the Marine Corps invasion planners took into account the neap tide.