A small detachment of Underwater Demolition Teams(UDT) had participated in the Battle of Kwajalein in January 1944. Still, during the attack on the Mariana Islands and the Battle of Saipan in June 1944, UDT would make its first significant appearance on a large scale. Using a swimmer slate and a sounding line, the men would determine the water depth within the reef that encircled the island, look for potential landing obstacles, and mark paths for the tanks to safely make it ashore without being swept away by deep water. The landing forces used fishing lines and buoys to map out a grid that they would use to get ashore once they reached the shore. This duty would be carried out in broad daylight to make matters even more dangerous, right in front of the Japanese defenders’ eyes.

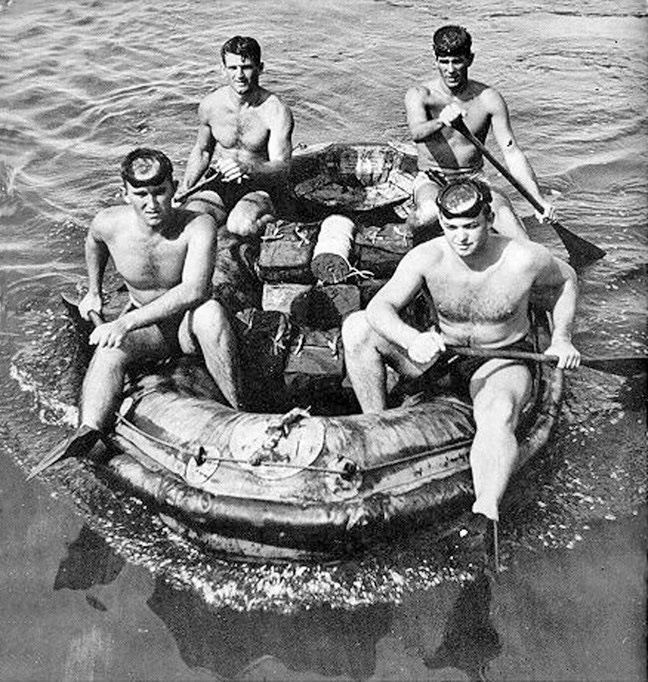

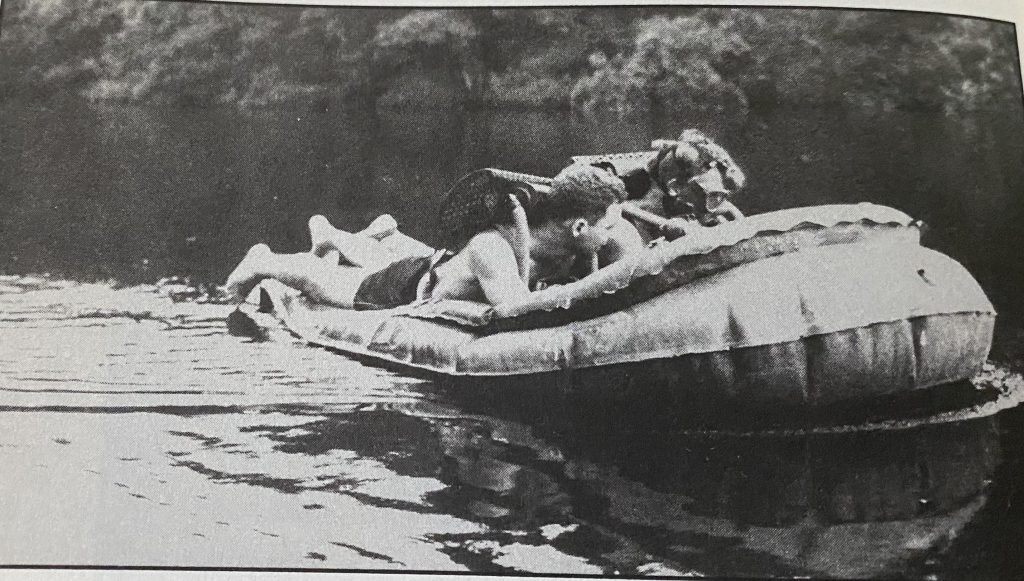

Draper Kauffman and his two Underwater Demolition Teams (5 and 7) left their cramped crew quarters on the APDs Gilmer and Brooks as the sun rose on June 14, D Day minus one, and began their part in the action, piling into four landing craft that arrived alongside the ships. Swimmers were assigned to survey the approach to a specific beach on each of the 36-foot-long LCPRs, which had sixteen swimmers on each vessel. The Japanese had not anticipated the sheer volume of preparation fires that would reach such a crescendo. They were also not expecting to see swimmers side stroking toward them as the sun rose, led by officers in vessels no more impressive than a motorized black mattress, puttering in via an electric motor toward the well-defended shore as the day broke.

As is customary for Kauffman and his teams, they were only minimally outfitted, sporting trunks, swim shoes, a face mask, and a sheath knife. They didn’t have any fins or snorkeling equipment. Besides the buoy and reel, each pair was also equipped with an acrylic slate and a grease pencil for drawing on the water. Even though they had been trained how to use oxygen–beryllium chloride rebreathers, they did not have any on them at the time. The equipment was heavy and inconvenient. Most of Kauffman’s team leaders decided to ditch their bulky radios as well, in favor of a more rapid swim. To do this, they used a basic sidestroke known as the “invasion crawl,” which allowed them to swim across the reef and into the lagoon. Compared to an overhand crawl, it was less exhausting and produced less splash.

In Kauffman’s mind, they had resigned themselves to the fact that their chances of escaping with their lives were slim. Under Kauffman’s command, Team Five would reconnoiter the Red and Green beaches, while UDT 7 would investigate the Blue and Yellow beaches under Lieutenant Richard F. Burke’s command. He kept his third team, UDT 6, in reserve, anticipating that his casualties would be as high as fifty percent, and he was prepared for the worst. As the LCPRs neared the reef, Japanese artillery shelled the area around the ships. The frogmen began rolling over the gunwales into the water, one pair every twenty-five yards until they reached the water’s surface. A red buoy was dropped by each duo, which was attached to the point marking the seaward beginning of their route to aid them in orienting themselves for the return. When enemy shell splashes began walking in the direction of the buoys, Team 7 executive Sidney Robbins ordered the crews to stop putting them in place immediately. He also made the decision right there and then to discontinue the string reconnaissance technique that Kauffman had instructed them in. He knew it would not be easy, and he was right. The less they had to carry, the better their chances of surviving the harrowing experience that lay ahead. Kauffman and his companion, a frogman named Page, started their puttering daylight run toward the beach shortly after 8:30 a.m. by turning on their small outboard electric motor.

Kauffman wanted his team leaders to maintain some semblance of awareness and potential control over their eight dispersed swimming pairs, so he provided them with motorized mattresses as their starting point. According to Kauffman, he would later call them “the dumbest idea I’d had in a long time,” according to Kauffman. “They were the most magnificent targets,” says the author. He’d been told about the large sharks and man-eating giant clams that were rumored to be in the area during briefings. However, he had advised his men not to take any precautions against them because he believed that more significant threats lay ahead, including Japanese coastal guns, beach pillboxes, and mortars, to name a few examples. Kauffman was forced to abandon his floating mattress experiment due to the sheer volume of incoming fire. As soon as he realized that the morning naval bombardment had done little to aid him in his endeavor, the writing was on the wall for that bizarre scheme. Kelly Turner would be disappointed to discover that his orders to his fire-support ships—target the beachfront first, then slowly move fire inland—had gone largely unheeded by the boats. The first salvos were fired too far inland to neutralize the coastal defenses effectively. Because they could not maintain direct radio contact with the bombardment ships, the frogmen were unprepared to deal with unexpected events. Upon arriving at Blue Beach One, Sid Robbins of Team Seven was taken aback by discovering that mortar teams had set up a firing position out of a cluster of a dozen Japanese barges moored to the pier. Because of the intensity of the barrage that was rained down upon them, Robbins’ swimmers could not recognize Yellow Beach One in the first place.

After several failed attempts, this detachment returned to the Brooks with only two men seriously injured, which seemed to be a small number considering the circumstances. When all of his swimmers returned to the reef, Kauffman informed them that their landing craft would be waiting for them. It turned out to be an unpopular order, as two of his men went missing due to the demand. But, with mortars dropping around his boats, he didn’t want to risk losing any of the critical information he had gathered about the reef and the lagoon. It was also discovered that the route the Marines had envisioned for their waterproofed tanks, which were to be paddled ashore in the wake of the assault waves, would lead them straight into disaster. The road was potholed, and the water was too deep for these improvised amtracks, which were never intended to swim and drowned quickly due to their lack of design. A smooth path that crossed the lagoon in front of Red Beach Three and led diagonally onto Green Two, Kauffman believed he had discovered a better way to get there. After work that night, Kauffman had his most skilled draftsmen create charts based on the lagoon soundings. Commanders of amtrac and tank battalions and transport groups would have hand-drawn maps delivered to them when the invasion force arrived before the next sunrise, allowing them to plan their maneuvers.

Admiral Hill summoned Kauffman to General Watson’s quarters at some point in the evening. “What in the hell is this I’m hearing about your changing the route for my tanks?” the Second Marine Division’s commanding officer inquired. He had wanted them to swim across Red Two to get to the other side.

“General, they’re never going to get through there,” Kauffman assured him, pointing to his maps.

“All right, that’s fine. But you’re going to be the one who leads that first tank in, and you’d better make damn sure that every single one of them gets in safely and doesn’t drown.”

After reading Kauffman’s report and taking into consideration his calm, unwavering confidence, Kelly Turner began to believe that the idea of sending twenty thousand Marines ashore in these newfangled swamp buggies might work out after all.