The recent article regarding the Army’s intent to sole source additional M4 carbines from Colt inspired quite a bit of debate about replacing the gun, or at least modernizing it. As for replacing it, the Army already has a plan, and that is Next Generation Squad Weapons which is the example used in the article from the Army I’m sharing today to explain just a bit of the process to procure a new capability.

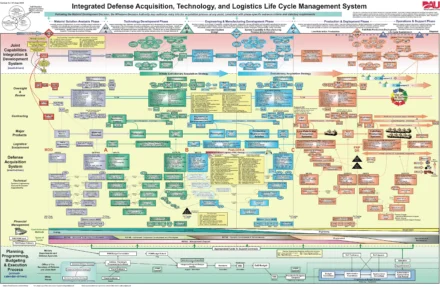

The image above shows the whole process to get new gear. It’s a multi-year path and is never as simple as going down to Dick’s and plopping down a credit card to buy some guns.

The system isn’t broken, it’s just slow. It exists for a reason, and that reason is that the military doesn’t want to spend potentially billions of dollars on something that doesn’t do what they need.

As for the M4 carbine, I think they’ve still got several decades of life in them and I suspect that eventually the Army will get around to improving them, after applying lessons learned from high pressure ammunition to 5.56mm. I don’t think we’ll see a new gun, but rather a new Upper Receiver Group to handle a new high pressure 5.56 round, sometime in the early 2030s.

Here’s the article, and just a little look into what the acquisition community does for our military.

Behind the scenes, critical process ensures weapons systems ready for Soldiers’ use

By Ed Lopez, Picatinny Arsenal Public Affairs October 1, 2024

PICATINNY ARSENAL, N.J. — One of the most anticipated and well-received weapons fielded in recent years has been the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) System, which consists of the XM250 Automatic Rifle, the XM7 Rifle, and the XM157 Fire Control.

Three types of 6.8mm ammunition are also part of the system and will replace the currently fielded 5.56mm ammunition. The XM7 Rifle is the replacement for the M4/M4A1 carbine for Close Combat Force (CCF) Soldiers and Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFAB).

The XM250 Automatic Rifle is the replacement for the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) in the automatic rifleman role for CCF Soldiers and SFABs. The XM157 Fire Control is a magnified direct view optic with a laser range finder, environmental sensors, ballistic solver and digital display overlay. It is compatible with the XM7 Rifle and XM250 Automatic Rifle.

While news media reports have documented the satisfaction and enthusiasm of Soldiers who have used the new weapons, far from the spotlight is a critical process without which such fieldlings could not happen: the Army’s Materiel Release process.

In military usage, materiel refers to arms, ammunition and equipment in general. Note that the term is spelled with a second “e” in the end, unlike the more common word “material.”

The Materiel Release process ensures that Army materiel is safe, suitable and supportable. That is where the simplicity ends. To achieve those goals requires a tightly woven process of testing, assessments, and approvals, along with coordination with internal organizations engaged in the Materiel Release process and with external organizations.

In the case of the Next Generation Squad Weapon System, the Materiel Release was performed at the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM) Armaments Center. Although the Armaments Center is best known for its research and development activity (it developed the 6.8mm ammunition to obtain optimum performance), another important role is to shepherd through the process a Materiel Release when appropriate.

The Army’s required Materiel Release process performed at the Armaments Center is conducted on behalf of Program Executive Offices (PEO) that fall under the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics and Technology, or ASA (ALT).

Although the Armaments Center supports all such offices, Joint PEO Armaments and Ammunition (A&A), PEO Soldier and PEO Ground Combat Systems are the most frequently supported.

In the case of the NGSW System, two PEO offices were involved: PEO Soldier for the two rifles and fire control system, and JPEO A&A for the three types of ammunition.

However, there is another key party involved before materiel can be fielded: the Materiel Release Authority. “At the end of the day, our Materiel Release mission at the Armaments Center is to provide a recommendation to the Materiel Release Authority, which is the Life Cycle Management Command (LCMC) that has the sustainment mission for the item,” explained Thor Gustafson, Materiel Release Coordinator at the Armaments Center.

“In the case of weapons sustained by TACOM, the Armaments Center makes a recommendation to the Commanding General of TACOM, saying it’s ready to go for the type of Materiel Release being pursued,” Gustafson said. “It has all the documentation required and we’ve done all our due diligence.”

If it’s an ammunition item, the Armaments Center makes a recommendation to the Commander of the Joint Munitions Command (JMC) that it’s suitable for the type of Materiel Release being pursued.

However, getting to that final stage, a sort of “hand-off” to the “Gaining Command,” is a complex process, with potential delays if it veers off course or stalls at some juncture. However, an underlying impetus to completing the process is a parallel awareness that the process is critical to getting needed systems into the hands of Soldiers.

The most common types of materiel releases conducted at the Armaments Center are Full Materiel Release, Conditional Materiel Release, Urgent Materiel Release (the category for the NGSW system) and Software Materiel Release. While each type of release may have its variations, there are generalized procedures that must be followed.

The Materiel Release Office plays a central role in guiding the process for those employees who are unfamiliar with the undertaking, which, when depicted by a visual process map, may seem like an intimidating labyrinth.

“There’s a lot of variables,” Gustafson said, “so that’s why I can never say how long it’s going to take from start to finish. There are so many interdependencies and there’s so many different types of issues that may come up, or specific nuances for a program that we have to kind of live through and mitigate and move forward with.”

A process map is one way to envision of the magnitude of the entire process, but a rough estimate of how long each step might take is just that. An estimate.

“I caution people that those are nominal durations for these steps, which might be helpful, but every program is different. Some programs can get through an Urgent Materiel Release in less than 180 days. And some of them can take significantly longer, maybe years. Our role is to get product to the field as fast as we can while still meeting all the regulatory requirements.”

Gustafson recommends using program management software to keep track of all the document requirements, when they are due, and who is responsible for meeting designated deadlines. “You input the dates for all these documents, and you look at the predecessors for each of them, and you can run what they call a critical path,” he explains.

“If I know a critical path, I know where I need to put my attention at what time, at what month, what day. For example, someone might have the hot seat this week because his documents are due. If his document or his assessment slips by a few days, we can now see what the trickle-down effect is for all the other documents that have a dependency on it, if there is any, and then how that might affect our end date to get the materiel release approved.”

A complicating factor to the materiel release is that not only does documentation have to be produced and routed within the Armaments Center, but also collected and exchanged with external organizations such as the Army Evaluation Center, the Army Test and Evaluation Command, and the Defense Centers for Public Health.

One of the crucial early stages of the materiel release process is the Integrated Project Team (IPT). Typically, the team is headed by a project officer from one of the Program Executive Offices who manages the overall program, project or release item. However, teams also require other essential members who contribute to meeting the overarching goals of ensuring safety, suitability and supportability.

Other team members may include a Safety Engineer, a Quality Engineer, an Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) specialist and other representatives from external organizations. “It’s everybody who has a stake in the particular program that’s pursuing the materiel release,” Gustafson said.

Because there are various interdependencies for certain documents and approvals, frequent and ongoing conversations are essential, Gustafson said.

“An example would be if we have an item that’s going for an urgent materiel release and perhaps it’s not fully meeting a requirement that the user wanted. That means that suitability is impacted. If it’s not as suitable as intended, it’s possible there could be a safety impact. So that means our safety engineer has to be aware.

“And that safety implication may now require a technical manual update, which falls under supportability. A technical manual is used by Soldier to learn how to use an item. So, you can see how the three tenets of safety, suitability, and supportability can all be impacted by one particular issue because it has implications across the board. And that’s why the regular meetings with the IPT and frequent communications are really important to make sure that we get through this process as effectively and efficiently as we can.”

Other Armaments Center employees who play invaluable roles sit on review boards. They have functional expertise in specific areas, such as fuzing or software, and can vote to concur or not concur on whether standards are being met.

“We rely on them because we need an independent review of the item from somebody who’s not involved or engaged with the program that’s being reviewed,” Gustafson said. “They can make sure that we’re doing everything we need to do–the right things–and that we’re not missing anything.”

Working backwards from the anticipated release or fielding dates, anticipating all the steps, requirements and approvals, can help to get a handle on all the elements required to meet objectives, Gustafson said.

That approach was especially helpful in the case of the NGSW system, with two different rifles, a fire control system, and three different ammunition types.

“Basically, we did a lot of these meetings in November to get this thing approved to go out to the field by end of March, early April, which I think is tremendous to execute six different items that went through this Materiel Release process in a fairly quick amount of time.”

The number of materiel releases that are generated through the Materiel Release Office at the Armaments Center is difficult to predict or balance, said Gustafson.

“In some years, we only have a handful and other years, we have a plethora of all these programs. And we’ve got to maintain some sanity, right? So we balance our workload when we have many Materiel Release actions and prioritize the programs to best support the warfighter and their needs.

“I’ll say a lot of what we do is prioritization, giving the right attention at the right time to make sure these programs are successful.”

Making sure that the Materiel Release process is properly completed is an ongoing mission at the DEVCOM Armaments Center. A small sample of other recent Materiel Releases from the center include:

M821A4 81mm HE Mortar Cartridge, Full Materiel Release

M3A1 Multi-Role, Anti-Armor, Anti-Personnel Weapon System (MAAWS), Full Materiel Release

M153 CROWS V4.2, Full Software Materiel Release

Mk258 Mod 1 Armor Piercing Fin Stabilized Discarding Sabot with Trace 30 x 173mm Cartridge Follow-On, Urgent Materiel Release

XM1198 30mm HE Dual Purpose Self Destruct Cartridge Follow-On, Urgent Materiel Release

XM950 30mm Practice Cartridge Follow-On, Urgent Materiel Release

“One of the most anticipated and well-received weapons fielded in recent years has been the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) System, which consists of the XM250 Automatic Rifle, the XM7 Rifle, and the XM157 Fire Control.”

Not true at all. Go to the shoots at Ft.Moore for example.

I’ve always thought it’s a better idea to replace the 240 and 249 with the XM250 while kicking the XM7 to side or at the very least push it as a DMR.

From everything I’ve read, heard, and seen, the reviews is that these weapon systems are a mixed bag of good and bad. The biggest gripe that keeps popping up is the total weight of the XM7. GBRS Group did a collaboration with Classic Guns YouTube. To sum up (from what I got) is that the XM7 wouldn’t be the weapon of choice for certain SOF units that conduct lots of CQB kind of stuff.

Some Guy is ill-informed.

“As for the M4 carbine, I think they’ve still got several decades of life in them and I suspect that eventually the Army will get around to improving them, after applying lessons learned from high pressure ammunition to 5.56mm. I don’t think we’ll see a new gun, but rather a new Upper Receiver Group to handle a new high pressure 5.56 round, sometime in the early 2030s.”

For all the “hate” a rack-grade M4 gets it really is “good enough” for what it is being asked to do. Notional upgrades in barrel length or floating handguards may increase accuracy, capabilities, etc but at the end of the day it is still launching that same rack-grade, issued 5.56mm M855/M855A1. The juice isn’t worth the squeeze unless you can justify the cost in upgrading.

I believe Sig’s thinking is certainly leaning this way as was posted on here not that long ago as they showcased the same ammunition upgrades used in NGSW. They’re positioned with the ability to have the most research and engineering ahead of the game and with their own upper capable of being dropped onto an M4 lower. NGSW is still meant for the fire and maneuver elements so upgrading combat support elements to better match capabilities will be forthcoming.

Firstly, great article SSD. Love the content.

Sure procurement is hard, but not impossible. Ukraine is a war being fought on the ground by individual small units. You would think that procuring updated small arms would be somewhere on the priority list for Army leaders (NGSW is a debacle, we all know it, Army and SIG wont admit it).

The US Army spends between $650-700 on each M4A1 it purchases. It is entirely possible that they can get the same QA/QC but better performance buy purchasing any number of off the shelf AR15/M4 variants from quality American manufactures.

Sure it isn’t a “phased plasma rifle in a 40-watt range” level upgrade, but the firearms industry has made 30 years of progress in manufacturing AR15s/M4s since the M4 design was made. COTS rifles are a little lighter, a little more durable, a little more reliable and a little more accurate for the exact same money.

We know this from all the M4 reliability trials in mid-2000s where M4 performed the worst in dust test despite extra help via biased lubrication schedule.

https://www.army.mil/article/6627/army_tests_carbines_for_the_third_time_in_extreme_dust

We never needed the XM8 or piston guns, or NGSW (mM250 is cool but should be in 5.56) or any of that nonsense. A modest mid-life upgrade, of this solid time tested rifle design, would fix many of the issues and is very doable with minimal if any disruption to the force. Do it now BEFORE another war breaks out. Now is the time.

Hell, if the Army spent the money is “disappeared” from Soldier’s BAS on updated AR15s then we would already have made the switch by now with money left over for Surf and Turf.

I don’t necessarily disagree with your thoughts, but a fuller picture might be useful.

While M4-pattern guns are commercially available that outperform the standard-issue rack grade M4/16 FOWs, the “little lighter, a little more durable, a little more reliable and a little more accurate” options simply don’t move the needle from the Big Army perspective.

As someone who relied on that gun multiple times overseas, my thought is that “hell yeah, gimme a little more hot sauce.” However, knowing all of the testing, documentation, and re-engineering some of those options might/likely be needed, those few drops of juice simply aren’t worth the squeeze for a million man Army.

And while the extreme dust tests did show a higher incidence of issues of feeding, chambering and extraction, all of the other guns the M4 was compared to had a higher incidence of ruptured cases. It could be argued that immediate and remedial action, along with a heavy douche of lubrication, is preferred to dealing with a ruptured case stuck in your rifle.

Now, before anyone jumps all over me because you get the impression that I think the M4A1 is the bees knees, the abandoned M4A1+ PIP needs to be resurrected because reasons. The current incarnation of the M4 can still be improved upon. And PIPs are an easier Win than going with a new commercial weapon option, no matter how much it might look like the same ol’ AR.

Personal thoughts on the M250 being chambered in 5.56mm instead of 6.8mm, doing that leaves too much capability on the table. What Squad Leader, Fire Team member or Automatic Rifleman wouldn’t want the extended terminal ballistics that the 6.8mm brings to the table. When Johnny Taliban knew to stay outside of our maneuver space and initiated contact with PKMs from out yonder, the 5.56mm is just lacking as a response.

Something else to consider is that the Army just posted a Sources Sought Notice (#W15QKN25X14VU) for M240 6.8mm conversion kits to support the XM1186 6.8mm general purpose cartridge. It just kinda informs the discussion, slightly.

Anywhoo…jsut some rando thoughts.

I don’t disagree personally; there are upgrades that could make the M4A1 notionally better. I’m also pragmatic and realize you or I buying a part from Brownells on our own dime is not the same as managing a fleet of a million carbines.

Show me an attachment that turns the wasted heat and energy of the deflagrating gunpowder into a directed energy weapon (not necessarily in the 40w range but it would be nice…) and I’ll get excited. A mass, pure fleet reissue of every M4 to a notionally better M4 is like changing the word happy to glad in a performance report unless you’re drastically upgrading performance of the 5.56mm ammunition it eats.

SSD’s comment that NGSW-type ammunition could very well do that, and then, assuming a new upper/bolt combo would be required to safely/reliably take those pressures would make an upgrade (or even outright replacement) warranted.

Have you grouped 855A1?

Yes.

And it would group a lot better out of a rifle with a technical specification of 1-2MOA instead of the M4A1 with an accuracy requirement of <4 MOA.

The M855A1 is capable of more accuracy than the rifle shooting it. SO if you want get the accuracy value out of the M855A1, then feeding it into a more accurate rifle is how you do it.

That was directed at DSM but the point being that it groups pretty well in the M4A1 in my experience.

Which was sort of my point in a way. When you’re putting in the same ingredients you may get a slightly different cake at the end but it’ll still be the same cake. Any 5.56mm shoulder fired firearm in the 7-8lb weight range will all perform fairly similarly in a given set of conditions.

I would be very wary on using that 2007 extreme dust test. If you don’t mind the lengthy read, this guy does a very good indepth analysis of the test results.

https://elementsofpower.blogspot.com/2008/01/extreme-dust-test-m4-and-others.html?m=1

The system isn’t broken, it’s just slow. It exists for a reason, and that reason is that the military doesn’t want to spend potentially billions of dollars on something that doesn’t do what they need.

I think the government procurement system is shown that it is horribly broken. Almost never meeting timelines, always over budget. Inside and outside of DOD this is a problem so it’s not pointing fingers solely at the military. Purchase, use, break, learn is more efficient. Congress plays games all the time by forcing purchases from preferred vendors (constituencies). Forcing purchases from small, veteran owned, minority owned etc has caused a LOT of bloat. The system is broken.

Agreed

We built the LCS ships that hulls that crack and can’t go into rough seas, F35 is a maintenance nightmare, Multiple Bradley replacement attempts and still no vehicle into 2040 (supposedly). We are behind on submarine, destroyer and carrier production by a decade, our frigates that were suppose to be completed by next year are still a half-completed schematic. Procurement for new tech like drones and EW are just now getting underway when ISIS was using them agaisnt us in 2014. And meanwhile I have units with UCP pattern gear and just today in Command and Staff it is reported that CIF is OUT of OCP pattern OCIE. But we still have to turn in out UCP pattern OCIE. So Soldiers will be without ECWCS, MOLLE Rucks and Sleeping Bags.

Has Ukraine taught us nothing? The speed of change on the battlefield is measured in weeks and our procurement processes is measured in decades. We MUST do better and no tinkering around the edges will do. A wholesale re-write is needed.

The Defense Primes need to be broken up. In 1980s we had over 50 major defense contractors, now we have 5. It is a big, slow, fat, cartel. The rules we have today were written by their lobbyists to benefit them, not the war fighter.

The system is broken.

DLA has massive amounts of inventory of MOLLE, ECWCS, and Sleeping Bags and is dropping their procurement volumes due to it. If your unit is lacking it isn’t an industry issue, it is a Mil supply chain issue.

You both bring up some good points. However, I have some questions.

You mention “Purchase, use, break, learn” is more efficient… That’s exactly what the procurement system does. Using the NGSW as an example, they purchased a small lot of the weapons, and put them through production qualification testing for every round of selection. That saw several weapons put through a service life’s worth of ammunition to determine things like mean rounds between failures/stoppages, dispersion, etc. Then it was evaluated by Soldiers who provided feedback which was incorporated into the next round of ‘purchase, use, (maybe) break, learn.’

Any weapon that is going to be put into the hands of Soldiers has to go through safety confirmation testing to ensure that it doesn’t explode in the hand of a Soldier while they are evaluating it. That takes time. Congress isn’t going to just let the DoD issue weapons that have not been through this type of testing (if for no other reason than the optics it might give them for re-election).

This means that testing will be required to be done prior to something being fielded. And quite frankly, I’m glad they do it. Testing under controlled, repeatable conditions catches a significant percent of all the issues that may come up with a weapon.

“Has Ukraine taught us nothing? The speed of change on the battlefield is measured in weeks and our procurement processes is measured in decades. We MUST do better and no tinkering around the edges will do. A wholesale re-write is needed.”

Speed of change is one thing. Speed of reality is another. Believing that we will be able to field everything to the DoD in weeks is wishful thinking at best. As the article posted above mentions, what is the critical path for procurement? There are significant challenges in fielding things to units that are deployed, and units in the training cycle are training. so that means units that are in the tasking cycle are the only ones who are getting any of the fielded equipment. That is dictated by HQDA, so they would be the ones to change it. And depending upon what you are fielding, that more than likely aligns with what a vendor could reasonably produce in that given time period.

Using the example from the other article mentioned; If we were to select a vendor for the M4A2 upgrade (because that would likely be what it would be), how soon can they deliver enough weapons to field to a unit? Creating thousands of weapons, ensuring they pass lot acceptance testing, and having them shipped to a unit’s location takes time… And that’s assuming the vendor who wins the contract has the industrial capacity on-hand to produce the numbers needed.

Most manufacturers don’t like having machines laying idle for no reason, and milling machines needed for producing things like weapons at an industrial capacity can’t be bought and shipped via Amazon. So that means there are very few vendors currently who have the industrial capacity on-hand to generate what the DoD needs. Unless you are wanting to go the route of China/Russia and nationalize these industries and making multiple manufacturers produce a design, that is going to be an issue.

So how do you recommend addressing these problems? And keep in mind, that is just using the Next Gen Weapons as an example. Procurement problems are different depending upon what system is being procured.

Great points.

Considering the billions, or trillions, the DOD has wasted in the past on ideas that sounded great at first, it’s so nice to know their extremely complex chart is going to save us money. Or is the complex chart’s real purpose is to obscure exactly what they’re doing?

So having a process map (even if it is complex) is just a method of covering up mistakes? I don’t recall that being in the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), which I’m fairly certain they follow.

It looks complex because it covers the ENTIRETY of a system’s life cycle, which you could see if you actually opened the workflow image. That means it starts with requirements development on the left, and as you progress from left to right, you get closer to fielding the system. They also have to account for any challenges that may come up with disposal/demilitarization (e.g. you can’t just toss a tritium sight in the trash) on the far right. That becomes increadibly important to account for as soon as possible for something like a carrier/sub with a nuclear reactor.

Once again, depending upon what the system is, it could be fielded to every uniform member of the DoD, which is MILLIONS of people. Getting to that scale of numbers requires some complexity in managing fielding schedules, production timelines, etc.

But I’m sure you’re right. All those evil federal government civilians have just developed a complex thing just to confuse people and cover their tracks. You should get DoGE on the case right now.