“As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another.” – Proverbs 27:17

Although the above quotation is not specifically related to military training, it is very appropriate to the subject. Here is another exchange on the topic that many of you will recognize. “What kind of training have you men been doing?” “Army Training, Sir!” If you have seen the classic movie, you also know exactly why we do not let privates train on their own recognizance. As I said last time, planning, managing and conducting good training is a complex art – and in many ways is just as hard to master as war itself. In other words, it is a truly serious business requiring continuous attention and effort. Here are just a few points to ponder and discuss.

Let us start with the bad news. There have been and always will be training distractions and obstacles. Those routinely include conflicting priorities, constrained resources, and especially limited time. The trick is not to let the distractions sidetrack you – stay focused on the mission. True, it is something easier said than done. Still, good units and effective trainers work around or through those diversions all the time. Unfortunately, it is also true that a good number of leaders simply do not know how to properly organize and drive their training efforts. I especially worry about those squad leaders, platoon sergeants and platoon leaders who do not necessarily know what right looks like when it comes to planning and conducting truly productive training at the tactical level.

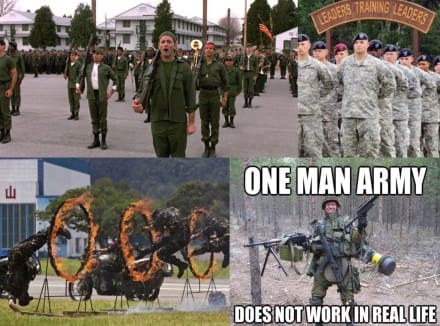

Just as you have to fight for intelligence on the battlefield, a unit has to fight to train. Know what you are trying to accomplish before you start. Plan to train but do not get fixated on your plan – be flexible. The training objective is what is important not the process. Many units spend a great deal of time trying to make the training look good and in the process lose sight of their actual training goals. Likewise, others become preoccupied with making the training uber “cool” rather than effective. My advice is to make sure your people are well grounded in the fundamentals before moving to master the high-speed flaming hoops drill (above).

Always train to a pre-established and reasonable standard and not to a time schedule. Training is never finished so do not become obsessed with the outcome of any one event. Do not be afraid of failure. Training exposes our shortcomings – if we are doing it right. Take advantage of the opportunity to figure out why you failed to achieve the intended training objectives. Was it a planning mistake, a resource shortfall or an issue of poor time management? Did the trainers know beforehand how to do the task required properly themselves? Take corrective action and do better next time.

Aggressively prioritize. Some training is always better than no training. A good trainer can get something out of even the most unproductive training evolution. At least the experience can serve as a reminder to build a better plan for future training events as mentioned above. Know who needs or will befit the most from the training. When time or other resources are limited, it is usually much better to train a few to a higher standard then everyone to a sub-par level. Look for non-traditional training opportunities and partners. Old school and new techniques can often coexist and reinforce one another. Do not presume that they are mutually exclusive or that one is automatically better than the other.

We have all probably seen the following counterproductive dynamic on qualification ranges more than once. In units with poor training habits, the intent invariably devolves into just cycling everyone through as fast as possible. The alleged point of the drill, i.e. improving unit marksmanship, turns out to be a pretense and not the true objective. Unfortunately, the longer-term and deeper negative effect can be debilitating to that entire unit. The leadership has revealed to their soldiers that they consider training an onerous chore that is to be competed as quickly as possible. Positive results are optional or even irrelevant. Sadly, that dysfunctional lesson will imprint some soldiers for the rest of their careers. They in turn will invariably infect others. It is an all too familiar cycle – but it can be broken.

Fighting back against bad training habits is hard but not complicated. It starts with leadership. Recognize that all unit training always involves team building AND leader training. Make sure to give your subordinate leaders something important to do in the training plan; and keep them visibly in charge of their soldiers as much as possible. This is especially important for those new sergeants who are leading for the first time and are trying to establish their credibility. In turn, soldiers benefit directly from seeing their leaders treated like valued members of the unit’s leadership team. In short, properly conducted unit training should professionally develop better leaders and concurrently result in stronger teams.

This also helps mitigate the problem of a unit hampered from accomplishing quality training because the leadership is overly distracted with the many other balls they are juggling. First, recognize and take advantage of the fact that every leader is part of a team and does not have to carry the burden alone. Delegate dammit! Moreover, a leader has to learn (and teach subordinates) not just to juggle but also how to judge those balls. Some balls are more important than others; and not all of them are made of glass. In reality, some balls can be set aside for another time or safely dropped. In doing so, we have the opportunity to demonstrate that unit leadership indeed considers quality training a high priority – though action rather than empty platitudes.

As I have mentioned before, there is a great book on training in WWII that I would recommend called “The Making of a Paratrooper” by Kurt Gabel. The author was a trooper going through Airborne training as a unit with the 517th PIR. He describes how the NCOs and junior officers would go off by themselves, learn a skill and – sometimes the very next day – turn around and teach it to the other troops. Not the ideal situation of course, but they made it work. They optimized, as best they could, their available organic assets to maximize limited external resources and extremely constrained time. They successfully met the challenge as an increasingly cohesive team and always took their training seriously. They knew that there was no other option. It also sets a great example to emulate even today.

Remember that even the most realistic training, conducted by the highest-speed units, has logical constraints that require soldiers to suspend disbelief when necessary. One simple example would be blanks or simunitions. If used properly, blanks are not going to kill or maim. Nevertheless, soldiers are expected to react to blank fire drills as if they were life-threatening live rounds. Likewise, when introducing simulated casualties the expectation is that soldiers will act in as close an approximation as possible to how they would respond to a real injury.

Teach your soldiers to value training though your example. It is true that not all training is fun and adventure. For instance, there is a lot of necessary repetition required to master the fundamentals of any individual or collective task. That can become boring. Bad weather can also make even good training more than a little unpleasant. Still, successfully building skills, competence and confidence – even in the worst of circumstances – is always a net positive for the collective esprit of a unit and the morale of individual soldiers.

Most of the veterans on this board could point to countless hours wasted on the tarmac or field site somewhere waiting for transportation. Did anyone in your unit consider trying to use that otherwise dead time to get at least some critical training accomplished? More often than not the answer is no. If someone made the effort, it was probably less than effective because it was not pre-planned but pulled hastily out of their fourth point of contact. Still, to be fair, I would give them at least partial credit for trying. Assuming they do better next time.

Time, money and ammunition are always finite resources. Never waste those precious assets – especially time! Always seek to get maximum effect from the resources you have. Do not waste time lamenting the resources you do not have. As with everything else we have been talking about, I would submit that the wise use of resources always comes down to the quality of leadership at the small unit level. Funny thing is that good leaders, despite the perpetual distractions and constraints, always seem to have enough to build good strong units. Even during periods when resources are much more constrained than has been the case in the last 16-17 years. Poor leaders, on the other hand, always seem to need more time, money or ammo – and still cannot get quality training results.

My final advice on training is that leaders must be willing to take risks. Most soldiers, myself included, like to think that we can always be as physically courageous as required in battle. Perhaps not ready, but willing and able to risk our lives if necessary. From my experiences and observations in various hostile places, I would say that is generally true enough. However, displaying moral courage is arguably much harder. In part, that is because the need for action does not present itself as unambiguously as it does in combat. It sneaks up on a leader over time. It often starts with the insidious – often self-generated – pressure to pencil whip a few training records so the unit looks good or to CYA. After all, training is not life or death and is certainly not important enough to risk damaging a career…or is it?

Now we are clearly talking about dedication to duty more than we are training. You have to ask yourself a question. How much do I really value training and how hard am I actually willing to fight for what might only be a modest and temporary improvement? That is an individual decision we all have to make for ourselves. The Army does constantly tell soldiers to do “the hard right over the easy wrong.” That is noble and righteous advice. However, it would be a mistake to think the institution actually cares. It does not. The Army is a soulless, unfeeling and ungracious machine; a whore who has never loved you – and never will.

If you are a whistleblower, no matter how justified the complaint, you will not be rewarded for your courage or you honesty. No exemplary service award is waiting for you; no building or street named in your honor; and you are not going to receive public recognition as the unit’s soldier, NCO or officer of the year. Worse case, you might even be punished. It should come as no surprise to any professional soldier that truly selfless service is always a bitch. None of that changes the fact that the right thing is always the right thing. In the end, all I can tell you is that principled leadership in training and war is never easy or painless – but I strongly recommend it anyway. De Oppresso Liber and good luck with your training!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

Tags: LTC Terry Baldwin

Thanks TLB! I spent many hours at Area J conducting hip pocket training as a young trooper and later as a Sqd Leader learning the fundamentals of a difficult craft. I believe those sometimes tedious hours/days set up my foundation to be a successful infantry Sqd Leader and SF Team Leader in combat years later.

T

Hip pocket training is undervalued. Some seem to expect to be told to put it together. This is the mark of a professional leader that cares. Every squad leader I saw training his troops when he didn’t have to was worth his weight in gold and often I learned something on how to train troops on the cheap.

Secondly is when assigned training don’t look for the old book and do what you saw. Sure meet the standard but exceed it if you can. Introduce new training techniques. PMI can be boring. A good trainer can make it challenging and interesting.

Finally, thanks LTC B for bringing up moral courage and professionalism. It’s very easy to complain. It’s hard to make it better.

Great article.

As a LE firearms instructor, this article resonates strongly with me. I will pass this article along to my fellow instructors.

Mr. Baldwin, great article! Book? You have the ‘magic’, my man! Keep it up!

This part of the article resonates.

“We have all probably seen the following counterproductive dynamic on qualification ranges more than once. In units with poor training habits, the intent invariably devolves into just cycling everyone through as fast as possible. The alleged point of the drill, i.e. improving unit marksmanship, turns out to be a pretense and not the true objective. Unfortunately, the longer-term and deeper negative effect can be debilitating to that entire unit.”

Even though we still deploy, many units never experience the “longer-term and deeper negative effects” of this “check the box” training, this in turn continues the pattern of marginal training within some of our units.

I have worked long hours for short term mediocre gain. We do what we must when the time comes, and it’s worth it for the few soldiers who benefit and learn from the experience. Looking forward, the real question is how to break the cycle? I would love to hear TLB’s opinion on how to keep experienced trainers and leadership within our formations. I’m beyond tired of leaders that are in key positions long enough to check the block and move on. Warrants used to be a good example of quiet, informal leaders and the keepers of institutional knowledge, but they’re becoming more careerist (especially in aviation) and our knowledge base is dwindling.

Thanks again for a great article.

Tom

Tom,

I gave a partial answer to your question during the discussion of the last article.

We are talking about effective “talent management” (TM) rather than one size fits all personnel management we are used to. Right now, TM is only a fantasy until someone shapes a real system to make it work. And that will have vast implications and impacts over training, professional schooling, promotions and every other aspect of personnel management.

In other words you just about have to tear down the entire current system to build an entirely new structure. It does not appear like that will happen any time soon. So we will have to continue to do the best we can within the current system for the foreseeable future. BTW, some of that is actually driven by laws and not just internal policies.

But I believe it has to be done. We are at the true Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) point that everyone thought we had reached in the mid-to-late 90s with precision fires. It is people not technology that ultimately matter.

We are still using essentially 19th Century mass army personnel management practices that are not going to serve us well in the 21st. We had better master the challenge of modern TM soon or I suspect we will pay a price in more blood in the not too distant future.

Oddly enough, some of the possible solutions may not be new at all. For most of our history, the Army had a reasonably effective regimental system that pushed personnel assignment and professional development decisions down to unit level.

That had the advantage of putting the decision on leaders who had better visibility on their soldiers. Now regimentalism is not without risks because it can be subject to cronyism if misused. However,, the mass mobilization for WWII and then the large post war draftee standing Army made centralization of those decisions seem desirable. I think it is past time to reevaluate that arrangement.

The British seem to do pretty well with their regimental system even today. So I would think that is one area we can explore. It seems that otherwise the Army would have to take on the burden of customizing and essentially micromanaging the career of each and every soldier at the DA level – and that does not seem practical at all.

The other area that I think might need re-evaluating is the pressure that has built over the years to manage Warrants and NCOs in patterns that are similar to Commissioned Officers. Officers have traditionally been generalist and Warrants and NCOs have always been purposely specialized and stabilized in their assignments. At least as compared to Commissioned Officers.

The intent now is to move those two cohorts from assignment to assignment and to make them more “well rounded” and less specialized in focus. The unintended consequence of these well meaning policies has been a weakening of the critical continuity and “institutional memories” those groups had habitually provided.

In other words, those policies may have been more counter-productive than positive. I would recommend reversing or at least modifying those policies so that NCOs especially are not subject to unnecessary career turbulence.

That would be a couple of personnel areas that I think could and should be adjusted to give the Army better options. At least we would have a better chance to manage talent more effectively than what we are doing today. One mans opinion.

TLB

Couple of thoughts, here:

One, the problem is not necessarily one of “personnel management”. That’s a bad concept, in and of itself–You don’t “manage” men in combat, you lead them.

The paradigm we’ve been using here came out of a post-feudal world, one that was intensely class-based. Thus, officer-NCO-junior enlisted. The parallels between the old noble/knight-yeoman-peasant structure of a feudal army shouldn’t need to be pointed out, but here we are. Is this structure reasonable, given all that has changed in our society? Look at the dichotomy that we used to be able to rely on, where the officers were educated, the NCOs had the practical military experience, and the enlisted were just there as spear carriers. Now, we’ve got junior enlisted that in some rare cases outstrip their officers in terms of technical education, and sometimes even in liberal arts education. Does the strict class-based hierarchy structure even make sense, given that the underpinnings have literally slipped away under it?

As well, the inherent power structure tends to attract a lot of the wrong personality types to command, in both the officer and enlisted ranks. How many penny-ante martinets can we all think of, men who existed seemingly purely for the pleasure of exerting petty power over others? And, what of the system that enables and encourages that, while destroying the interest, initiative and team feelings of their subordinates?

The way things are looking, I think that the formal hierarchical structure we’re used to is becoming increasingly irrelevant and dysfunctional. Part of that is because the hierarchy has turned into a structural strait jacket, and prevents adaptation and flexibility.

Think of the most successful organizations you’ve been around, or heard of: What do they have in common? Why was Robert Frederick able to turn the motley crew of troublemakers and former members of elite Canadian line units into the First Special Service Force, which flatly blew all training records out of the water when it came time for them to be assessed as conventional line combat troops by the bureaucracy?

Why is it that we solve a lot of our problems by selecting high-quality people, throwing them at the issue, and letting them flexibly deal with things on their own terms? Only to later let the pioneering problem-solvers move on, and the careerists to move in, turning whatever it was, whether the Sapper Leader Course or some other initiative, into an ever more constrictive and less productive “formal institution”?

If you look at it, you’ll find that there’s a veritable sine curve of excellence-solved problem-gradual decline-senescence going on with most of our institutions, with occasional punctuation of further excellence only when a crisis is met with, and new problems get thrown at old institutions.

Why the hell do we persist in doing things this way? Yeah, tradition, but… Sweet baby Jesus, but do we need to recapitulate the social mores of Georgian England to get good officers? Really? Because, when you go back and look at it, that’s the baseline for a lot of what we’re doing–What the guys who founded the republic thought about such things, and it wasn’t the rabid small-r republican types in the nascent United States that contributed significantly to our military culture.

It’s really jarring to realize, after hanging around the British Army for a bit, that there’s actually rather less social distance between their officer and enlisted corps than in ours, and that the officers have more fundamental trust in their senior NCOs in terms of skills and responsibilities than we do. It’s actually rather confusing, when you run into it.

Another thing that still flatly blows my mind is how top-down driven everything in the US Army is–You see very little change in terms of things flowing uphill from out in the field. Everything is dictated from the top, after someone from the field attains a position high enough in the food chain to effect change. The problem with this is that the person doing that is very often out of date by the time they get in that position, and then they don’t represent anything other than a very narrow snapshot of what’s going on across the force.

We don’t do broad synthesis and collaboration in an attempt to reach consensus about best practices the way we should. Every squad leader in a given field ought to be connected up in parallel, in order to enable better communication, and that ought to be true across the board. We’ve got the whole thing down for email to the troops, but when all it really does is enable transmission of irrelevant spam, what the hell is the use of it all? There should be a system going that cross-connects leaders of similar units at similar levels, and be easy enough to access that you could throw up a comment on a bulletin board laying out a problem, and have other people throw their solutions at you. We don’t do this. Why?

Hell, think about how we used to do cav tactics in the old days, the Indian Wars. The concept was that you’d disperse your troops, and then identify where the bad guys were, and you’d have a converging mass of troops hit them good and hard, all at once. Converging columns is how I’ve seen the technique described, and more than a few successful militaries have used it, like the Mongols. Maintain dispersal, identify the enemy, swarm the enemy from all sides, and disperse again after you’ve eliminated an element of his. This is an enormously effective tactic, and one we ought to take as meta-technique for how we will need to organize ourselves and wage war in the future. It’s a tactical/operational concept uniquely suited to the average American, who you can’t tell shit to, and who insists on reinventing the wheel for everything. Move it over into how we organize for war, train for it, and fight.

The static hierarchy is something that’s going to die, along with rote assembly lines. Custom one-off manufacture is probably going to be the wave of the future, enabled by print-on-demand facilities and other technologies. The dead hand of the mass industrial structure we’re familiar with is on its way out, and what will come next…? Do not be surprised if you start seeing things like weaponized toys turned out of repurposed automatic factories, carrying warheads just big enough to cripple a vehicle. We’re probably going to see a kind of war that only a few imaginative types have foreseen, one enabled by smart phone apps that weaponize civilians on the battlefield, build mesh networks, and turn toy drones into anti-tank weapons. Think you’ve got an IED problem now? Wait until the damn mines start following you home, looking for the fuel tankers so that they can inflict maximum damage on your unit.

War is going to change a lot more in the next generation than I fear we are ready for, and with the inflexible and maladaptive force we’ve got? Dear God, but I fear for the troops. These idiots still haven’t digested the knowledge that the commander is going to have to fight for battlefield circulation, and that the PSD is going to have to be an integral part of every unit from battalion up. We’re going to have to re-learn that lesson again, because the people running this cluster-fuck can’t seem to read the handwriting on the wall very well, at all.