A few days ago on this site some commenters noted that many professionals, especially leaders, do not have the inclination or opportunity to truly do any deep reflection on their craft until after retirement. For myself personally that has certainly been the case. Part of that process for me has been renewing the effort to learn more and reread and relearn some of the more challenging and ambiguous concepts I was taught earlier in my career. More on that at the end; but first please consider the synopsis below of a discussion I had recently in another forum.

Machiavelli is a fascinating and complex historical character. He was an early champion of a pragmatic and morally relativistic philosophy of realpolitik that ethicists would eventually label as consequentialism or utilitarianism; sometimes reduced to a simple statement that “the ends justify the means.” Machiavelli lived in a time of an almost constant series of conflicts between city states and Papal political machinations and territorial ambitions. Constantly shifting alliances, ‘court intrigue’ and reversal of military fortunes was the norm as ‘Princes’ maneuvered overtly and covertly for relative dominance. A real life chess match or “Game of Thrones” minus the dragons.

That was the political / military ‘game’ that Machiavelli enthusiastically participated in – albeit as a mid-level player with perhaps outsized influence – during his adult life. By the time he was in his late 40s he had developed a signature philosophy and made the effort to write it down and share it initially with his contemporaries and then with posterity. I have extracted just two quotations from Machiavelli’s The Prince that are illustrative of what he believed in and preached. “Hence it is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity.” And also, “Therefore it is unnecessary for a prince to have all the good qualities I have enumerated, but it is very necessary to appear to have them.” Ideas like that – in many cases taken out of full context – contributed to popular perceptions of Machiavelli’s views being both indefensible and amoral if not immoral. For the record I have always found Machiavelli’s thoughts to be rational and valuable if considered in their entirety.

Clausewitz tells us, “War is merely the continuation of policy by other means” and therefore “there can be no question of a purely military evaluation of a great strategic issue, nor of a purely military scheme to solve it.” Sun Tzu also highlighted “the close relationship between politics and military policy, and the high social cost of war.” But both of those men were proficient and experienced soldiers and viewed, referenced and wrote only briefly about politics from that limited perspective. Machiavelli, on the other hand, was an amateur soldier but was undeniably a professional and talented politician. He was able to describe – in terms that soldiers can relate to – what war looks like as seen through an unapologetically political lens. He innately understood what we now call power relationships and interpersonal dynamics.

Machiavelli’s ideas were controversial even in his own time. The Roman Catholic Church banned his writings. Later his philosophy became indelibly associated with acts of political extremism because it was explicitly used to rationalize genocidal policies like the NAZI “Final Solution.” Today terrorist organizations almost by definition use Machiavellian thinking to try to justify their heinous crimes (means) against innocents in furtherance of a twisted but in their minds sacrosanct goal (end). They obviously believe that their sick ends justify even the most despicable means – even if they never actually heard of Machiavelli.

But those disturbing facts should not be allowed to detract from the larger veracity and utility of Machiavelli’s astute perceptions. This may be surprising, but his philosophies are not just applicable to ruthless ‘bad guys’. “The ends justify the means” is in fact a fundamental and universal principle that is and always has been considered in all political and military decision making in democracies and dictatorships alike. Every leader applies that brutally honest standard to every consequential decision whether they acknowledge it or not. Oftentimes we say it in this more palatable way “it is for the greater good” but the underlying logic is the same.

I’ll share two examples. In the 1930s an organization called the “Tennessee Valley Authority” (TVA) was part of an initiative to bring electricity to impoverished rural areas. To do so required the displacement of thousands of people so that rivers could be dammed and valleys flooded. Many of those people did not want to go but were forced out – a good number literally at gun point. I would certainly be willing to argue that it was “for the greater good” but those people forcibly removed would not. And it represents just one of countless domestic political decisions that are clearly based on the positive ‘ends’ justifying the not-so-positive ‘means’.

Let us consider the recent deaths of civilians in a U.S. airstrike in Mosul. The accidental killing of civilians in war is not usually considered a ‘war crime’ unless there are other factors like ‘gross negligence’ involved. But a good number of people – even Americans – would likely consider any airstrike that apparently killed more than 100 innocents “an extremely wicked or cruel act” a.k.a. an ‘atrocity’. But those air missions in support of fierce house to house fighting by Iraqi forces remain our best ‘means’ of achieving the worthy ‘end’ of ISIL’s occupation of Mosul. So today and tomorrow and the next day pilots will climb back into cockpits and they will drop more bombs. The alternative is to do nothing – and that is not an acceptable option; not for us, not for the Iraqi government and ultimately not for the people of Mosul.

What is disquieting for most people is that the ‘good guys’ and the ‘bad guys’ use the same Machiavellian reasoning to justify their respective actions. But there is no avoiding reality. There are few if any truly important decisions that are black and white. A political or military leader would not be able to function if he or she cannot make hard and morally ambiguous gray decisions. The Legislative process would be impossible and even the most just war could not be prosecuted if the ends NEVER justified the means.

That is not to say that we have to therefore accept any and all ‘means’ in order to achieve our ends. No rational person would have supported massacring those people in Tennessee in order to dam a river. No leader in uniform thinks that “killing them all and let God sort them out” is an acceptable ‘means’ of liberating Mosul. It is illogical and bizarre to argue that one can somehow “save” a village (desired endstate) by destroying it (unsuitable means). There are serious and often harsh judgements to be made and scales of just and unjust, acceptable and unacceptable that leaders constantly try to balance.

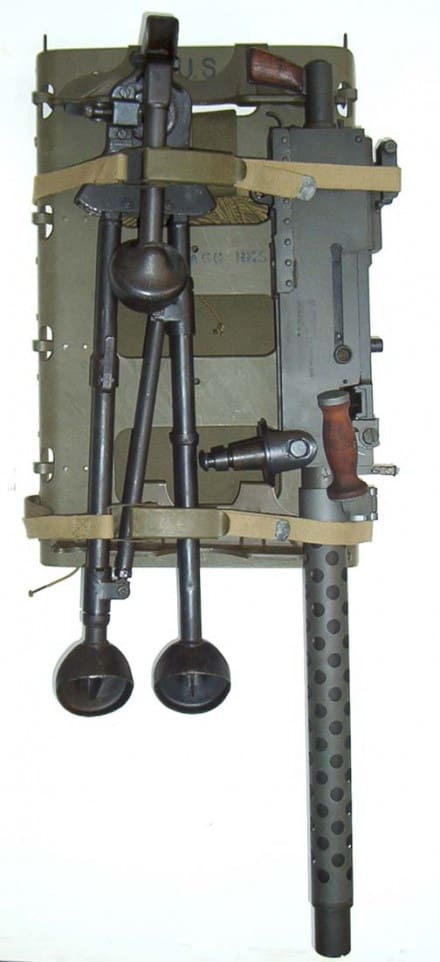

In professional military education programs today Machiavelli is usually examined and earnestly debated only in terms of ethical or unethical behavior. He practiced what we now call “situational ethics” as a virtue. But is it? Soldiers are in a business that routinely involves killing and destruction. In fact, as long as we follow the Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC), the controlled application of violence and the threat of violence by military forces are socially and legally sanctioned. We are empowered to use lethal force largely at our own discretion. But with power comes equal responsibility – and equal moral ambiguity. There are countless examples. Sherman’s march to the sea for instance. He essentially argued that by causing immediate suffering and burning Atlanta and other towns the war would end sooner and that was actually the most humane and militarily sensible thing he could do. I would agree. A similar argument was made in 1945 with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Again I for one would agree that Truman made the hard but ‘right’ decision.

That is what Machiavelli was able to describe so well – a realistic and pragmatic world view in which leaders have to make very difficult decisions that are invariably shades of gray and almost never black and white. When I order an air strike to support my ‘troops in contact’ I have to accept the fact that I cannot be sure that innocents will not also be killed by those bombs. Soldiers must make those kinds of tough decisions in war every day. Sometimes “situational ethics” is what one has to work with. And yes, that routinely looks a lot like the “ends justifying the means”. War is not morally or ethically neat and tidy – and neither is life – and that is why conscientious professionals still read and study Machiavelli for pertinent insight.

So why Machiavelli and why now you might ask? The answer is simple; to enhance my own education I signed up for an online Master’s Program in Military History this last December. It looks like a great learning vehicle and allows me to make good use of my remaining G.I. Bill benefits. And that is something I would recommend for anyone with educational benefits available that you have not yet used. Don’t let them go to waste. Of course the class workload has also cut into my ‘free time’ for other writing projects. I won’t lie to anyone; it hasn’t been very much fun to put my nose back against an academic grindstone. In my case it has been a very long time since I was last a student. But I firmly expect the end will justify the means.

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (RET) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments.