Training like you fight doesn’t just mean having your body armor on when you are on the range, and you should always practice basic skills whenever you get in the water. The best way to become a better diver is to practice and improve on the basic skills constantly. Here are some basic skills you should practice every time you get in the water.

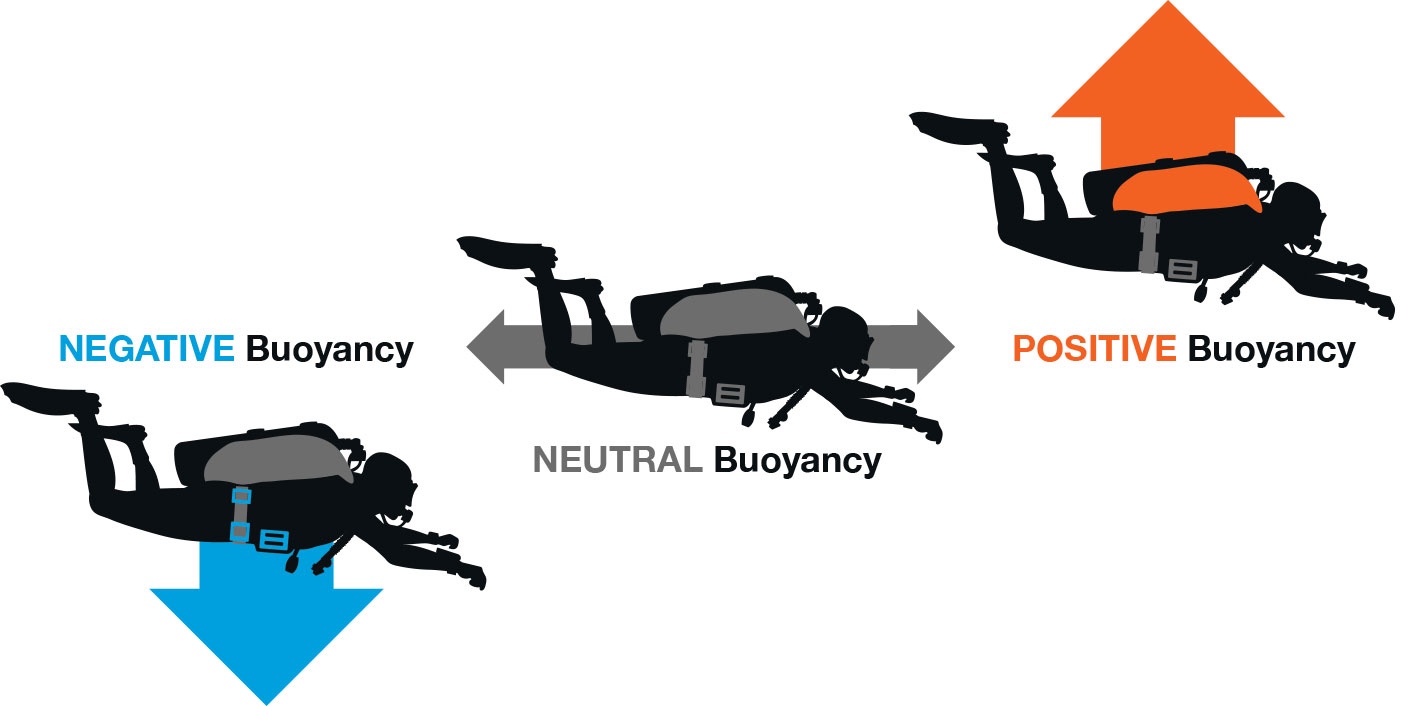

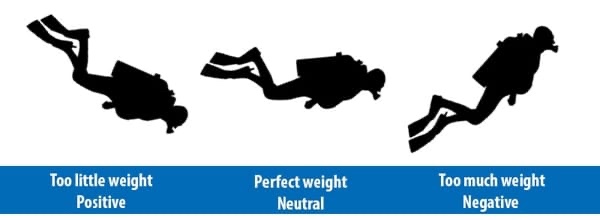

Buoyancy

This is one of the most critical skills for every diver to master. Mastering buoyancy is not necessarily a difficult task, but it requires a calm, focused mind, and practice. You will consume less air when your buoyancy is on point, and you will not risk shooting to the surface and giving yourself away or, worse, getting injured. To practice your buoyancy, try and be a couple of feet off the bottom of the pool using a body positions simulation to sky diving. Try maintaining the same distance from the bottom and now just using your fins spin to your left, then spin to your right, again holding your positions. Now once you have that, try, and move backward, besides just using your fins. This will help you with moving in confined spaces and around piers.

Descents

The descent should always be performed slowly and controlled. You will need to equalize the pressure in your ears as you descend constantly; that can mean every 12-18 inches 30-40cm for some divers. Descending too quickly can cause your eardrums to rupture, which can lead to more severe complications. A slow descent will also prevent silting on the bottom, which will decrease visibility. Also, practice your emergency descents. It will be the same as before but faster.

Clearing Your Mask

At some point, you will get water in your mask. So, it is better to practice in a controlled environment than to have not done it a long time and try and remembered when it is the middle of the night in someplace where you don’t want the water touching your face. If you have water in your mask, follow the clearing techniques you learned in your training. If you need to stop momentarily, alert your buddy so you do not get separated. You should be able to master this essential skill without having to stop. It would help if you also did this, allowing as a minimal number of bubbles as possible. Make sure you practice this when you are learning to use any diver propulsion vehicle.

Emergency Ascent

It is no different than practicing a down man drill. Well, other than the fact that you are in the water. Your emergency ascent may require that you share air with your buddy, swim in a controlled manner to the surface, you might have to drop your or their weights. I have had to do this when my dive buddy passed out, and I was so freaked out I didn’t have to drop anything to get him to the surface. It was also my first dive in the teams, and I thought he was dead Practice all types of emergency ascent techniques whenever possible to not panic when a real emergency occurs.

Hand Signals

Once you start diving with someone, you might come up with some hand signals of your own, like you have your head up, you’re a$$. But the essential hand signals will be used by everyone worldwide. You never know when you will be diving with someone from a partner nation, and that is all you have to go by. So, knowing the basics will help.

Going Up or Down

Use a thumbs-up signal to indicate that you are going up or a thumbs down to indicate the opposite.

I’m OK

Place your thumb and forefinger together, forming a circle, and leave the other three fingers extended upright. This is the same as you would say, OK, as you would above water.

Stop

Signal your dive buddy to stop by holding up one hand, the same as you would in any other instance. You can also use a closed fist like being on patrol.

Changing Direction

Just like with up and down, point your thumb (or your index finger) to indicate which direction you’re heading. You can tell again like on land.

Turn Around

To let everyone know it’s time to turn around, put your index finger up and rotate in a circle. Similar to rally-up.

Slow Down

Place your hand in front of you with your palm facing down. Wave your hand up and down to indicate that you need everyone to slow down a bit.

Level Off

To indicate that you want to level off once you’ve reached a certain depth, put your hand out in front of you, palm down, and wave it back and forth.

Something’s Wrong

Place your hand out in front of you, fingers spread and palm down. Wave your hand back and forth in a rocking motion. It is similar to the hand signal, maybe.

Help!

Wave your entire arm from outstretched by your side to over your head. Repeat the motion as long as you need to.

How much air do you have?

With the forefinger and middle finger hit in the palm of your hand to ask your buddy how much air is left in the tank. The usual response is in numbers.

I’m Low on Air

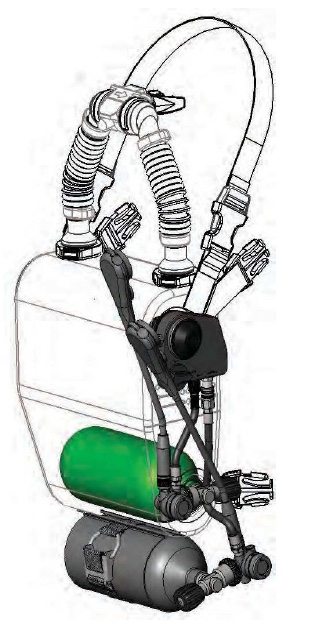

It takes practice to be able to make your air last. Clench your hand into a fist and pull it in toward your chest. Repeat as much as you need to indicate how urgently you need to resurface. When diving a rebreather, you should point at the pressure gauge. With some of the newer rebreathers, you can pull your gauge out and show it to your dive buddy if needed.

I’m Out of Air

Suppose something has gone wrong with your equipment, signal quickly and repeatedly. Place your hand, palm down in front of your throat, and move back and forth in a cutting motion.