It’s not hard to say that anyone who wanted to be in military Special Forces when they were a kid has watched the movie Gung Ho! So, in honor of Evans F Carlson’s Birthday on the 26th. He was one of the best leaders in military history and helped build today’s Special Forces foundation. He spends over two years in China with the guerrilla, learning unique tactics that he would bring to the U.S. to help fight the Japanese in WW2. We need more leaders like this in the world.

Evans F Carlson enlisted in the U.S. Army at the age of 16 and began his military career in 1912. He served in the Philippines, Hawaii, and Mexico, and less than a year after leaving active duty, he reenlisted in time for the Mexican punitive expedition. During his military service, he was wounded in action in France and was awarded a Purple Heart. He was promoted to Captain in May of 1917 and was made a lieutenant in December of 1917. After the war, he entered the Marine Corps as a private and gained the rank of second lieutenant the following year. Meanwhile, in Nicaragua, he was awarded the first of three Navy Crosses. In 1940, he became an observer in China during the years leading up to World War II and was impressed with the guerrilla warfare being waged against Japanese troops. While he was in Japan, he became convinced that Japan would attack the United States.

He advised General Douglas MacArthur of an impending invasion in the Philippines and the need for guerrilla units in case the Japanese army attacked. However, MacArthur ignored his recommendation.

Carlson returned to the United States and joined the United States Army again. Carlson and Merritt Edson advocated the use of guerrilla warfare as part of the Allied Pacific War effort. After Edson was assigned the 1st Raider Battalion, Carlson received command of the 2nd Raider Battalion.

Approximately 7,000 applied for enlistment in the 2nd Raider Battalion, but many people that applied were rejected. He asked each candidate about the political significance of the war. He later said he favored men with initiative, adaptability and held democratic views. James Roosevelt, the son of Franklin D. Roosevelt, became Carlson’s assistant.

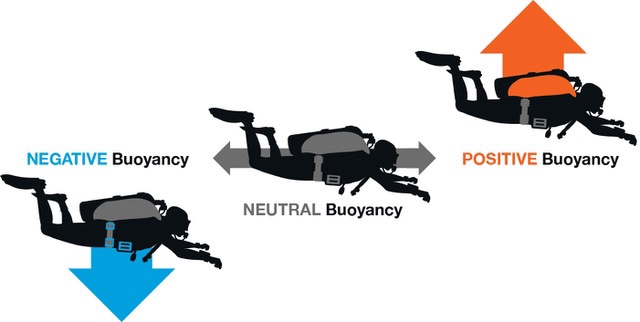

The Raiders learned the tactics employed by the Red Army against the Japanese. This practice involved learning how to kill people silently and quickly. To more effectively imitate the guerrillas of China, Carlson eliminated the privileges of officers. The same level of nutrition, wearing the same clothing, and carrying the same equipment were all factors.

Carlson’s field research into the Red Army convinced him that trust in the men in battle improved their performance and the belief in a better pollical system. So, he would provide information on how undemocratic governments are under Nazi Germany and Japan. Also, he encouraged the men to discuss their vision of a functioning society after the war.

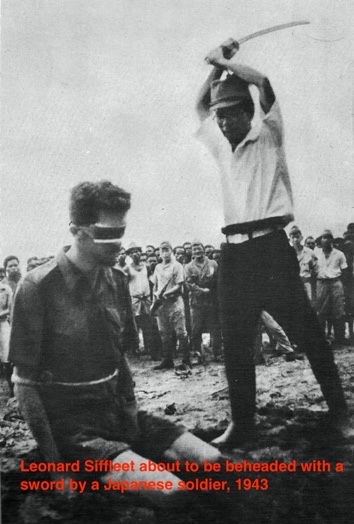

In August of 1943, Carlson and 222 marines left Pearl Harbor and landed on Makin Atoll. After two days of battle, Carlson’s men destroyed the radio station, burned the radio station’s equipment, and captured documents. Thirty marines were among the first to die during the Battle of Tarawa. As a result of this raid, the Japanese fortified the Gilbert Islands.

On 4 November 1943, the Raiders landed on Guadalcanal. During the next 30 days, Carlson’s man killed over 500 enemy soldiers and only lost 17. Carlson had been wounded and was forced to return to the United States for medical treatment.

Carlson’s superiors expressed concern about his unorthodox tactics and ideas. They were also concerned about his relatively close relationship with Agnes Smedley. This radical journalist was involved in campaigning for USA support of communist forces in China to help them defeat the Japanese Army in Asia.

In May of 1943, Carlson was promoted to be the Raider Regiment’s executive officer and was stripped of the direct command of his battalion during the Guadalcanal campaign. Carlson was also upset with his superiors by becoming involved in a controversial project of publishing pamphlets on the contribution of the Afro-Americans in the war. Carlson eventually returned to action in November 1943 at the battle of Tarawa. On Saipan, he received severe wounds when trying to rescue a radio operator who the Japanese had shot.

Carlson eventually returned to action at Tarawa in November 1943. During the Battle of Saipan, he was injured while rescuing a radio operator who the Japanese had shot. Being injured caused him to have to retire from the United States Marines after the war.

Below is the movie.

warfarehistorynetwork.com/2015/07/27/evans-carlson-forms-carlsons-raiders