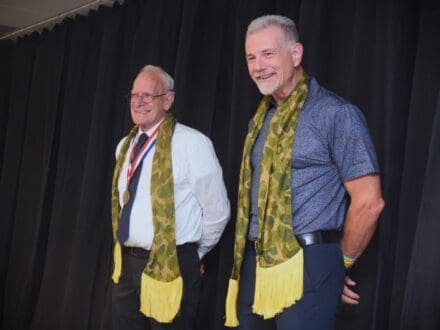

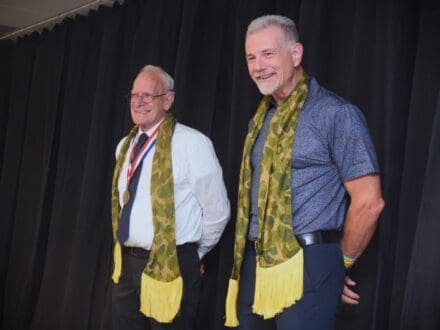

NATICK, Mass. – The U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Soldier Center, or DEVCOM SC, recently celebrated the remarkable careers and well-deserved retirements of two aerial delivery experts with a staggering 116 years of combined service to the Army and nation.

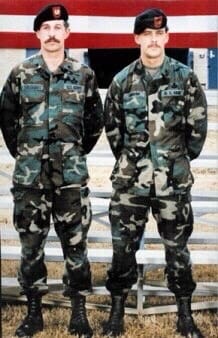

Long-time colleagues, jump teammates, Army veterans, and close friends John Mahon and William (Bill) Millette formally retired from their Army civilian careers during a joint ceremony held June 23 at the Natick Soldier Systems Center (NSSC), in Natick, Massachusetts.

They were presented retirement certificates, flags, and several aerial delivery-related gifts. They also received certificates of appreciation from the Rhode Island Army National Guard, a local military partner and host of the annual Leapfest International Military Static Line Parachute competition. Mahon and Millette have routinely competed in Leapfest, representing DEVCOM and the U.S. Army Natick Parachute Team.

Mahon’s 55-year career includes 31 years on active-duty and 24 as a Department of the Army (DA) civilian. Millette served 28 years in uniform on active-duty and in the Reserves, and more than 38 years as a DA civilian. Both men served their entire civilian careers at NSSC working for Soldier Center.

Since 2000, Mahon and Millette worked together on the Aerial Delivery Engineering Support Team (ADEST) under the center’s Aerial Delivery Division, performing the duties of a senior airdrop equipment specialist and senior mechanical engineer, respectively, where their military experiences, technical knowledge, and dedication to duty made them indispensable members of the organization and broader aerial delivery community.

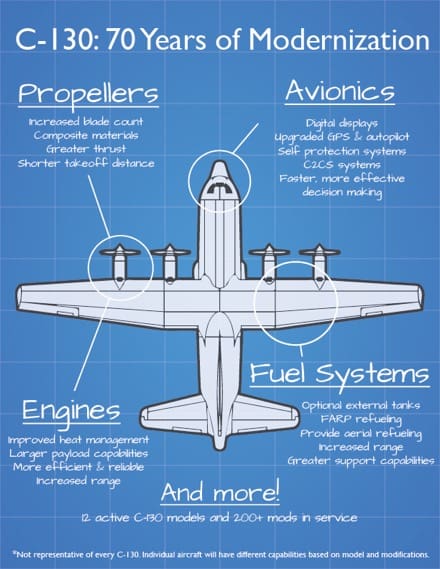

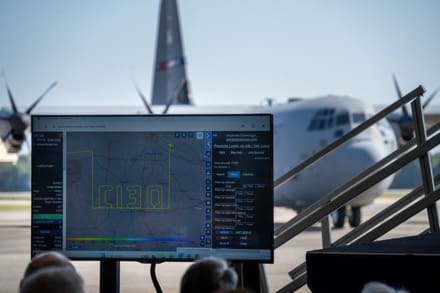

During their time at Soldier Center, Mahon and Millette were instrumental in helping research, develop, and evaluate numerous cargo and personnel parachute systems to advance new aerial delivery technologies. A highlight of their combined efforts and technical accomplishments includes: the Low-Cost Low-Altitude (LCLA) cargo resupply system, the T-10 Parachute, Modified Improved Reserve Parachute System (MIRPS), the All-Purpose Weapons and Equipment Container (AIRPAC), serving as the designated lead for the C-17 developmental test efforts, and the C-130J program, among many other programs and technologies implemented.

They also provided a specialized function for the airdrop community by conducting formal investigations into parachute-related accidents across the Department of Defense, or DoD.

“The years of service and the incredibly long list of contributions these two aerial delivery SMEs [Subject Matter Experts] have provided the DoD, both in uniform and in their civilian careers, is enormous,” said Richard Benney, associate director of the Soldier Sustainment Directorate and former supervisor to both men as the previous Aerial Delivery Division director. “Countless Aerial Delivery Division SMEs have engaged John and Bill for input on various technical issues over the years and routinely for their historical knowledge.”

“The experience and expertise that John and Bill brought to the aerial delivery community was invaluable and they will be sorely missed,” said Jennifer Hunt, deputy to the associate director of the Soldier Sustainment Directorate and former ADEST coworker and fellow Natick Jump Team member. “They were both instrumental in making both cargo and personnel aerial delivery safer and more effective for all the U.S. service branches.”

One specific area of technical expertise that Mahon and Millette were both well-known for, according to Benney, was being the Army’s “go-to” SMEs for investigating parachute malfunctions. Occasionally, these malfunctions resulted in a paratrooper or jumper fatality. Within a few hours’ notice, they could be traveling to an accident location and be gone for weeks while completing their investigations.

“Airborne accident investigations were one of the most serious and challenging responsibilities of their jobs at Soldier Center,” said Benney.

At the request of the Combat Readiness Center, they would be assigned as the technical leads of an investigation team charged with determining exactly what happened and why. This required extensive technical expertise, detail-oriented focus and stamina, as they often spent countless, grueling hours ensuring that all the evidence was gathered, accurately recorded, and that interviews were conducted professionally and thoroughly.

The results of these investigations helped ensure that lessons learned were applied to materiel changes or revised tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP’s) to make sure it would never happen again.

“The entire aerial delivery community greatly appreciates their attention to detail and thoroughness during these investigations,” said Benney. “Their dedication has directly resulted in making the airborne community even safer.”

Millette’s career at Soldier Center began in January 1986, when he started as a student under the DA’s Scientist and Engineer Co-Op Program and ended with his 2024 retirement.

Millette’s early work involved resolving construction difficulties with the G-12 deployment bag, modifying packing procedures for the 35-foot ribbon parachute used in the Low Altitude Parachute Extraction System, investigating the effect of 50% and 100% pocket bands on the opening time of the T-10 parachute, and supporting the development of the 60K airdrop system for the C-5 aircraft, including developing procedures for the extraction system and for the clustering of the 12 G-11 parachutes used in the system. He also managed the All-Purpose Weapons and Equipment Container (AIRPAC) and Parachutist Individual Equipment Rapid Release (PIE-R2) programs.

Millette was heavily involved with an Operational Support Cost Reduction (OSCR) proposal for the 15-foot static line, and the development of the Universal Static Line (USL). He combined his involvement with the OSCR program, the USL, and his experience with mountaineering equipment to modify a French snap hook so that it no longer needed to be sewed to the static line.

Instead, it could be easily joined with or removed from a static line, resulting in the current USL snap hook design that enables easy conversion between 15 and 20-ft lengths to accommodate jumping from various aircraft.

According to his biography, Millette also made significant contributions to the fielding of the Modified Improved Reserve Parachute System (MIRPS), including “a complete revision of the technical data package, testing of replacement pilot chute materials, resolving cone and grommet separation problems, identifying a solution to inadvertent deployments, and supporting technical manual revisions, contracting and quality assurance activities.”

Additionally, Millette was the lead author for the 2001 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics paper, titled, “Investigation of Methods to Improve Static Line Effective Strength,” and was a contributing author on two other AIAA papers, a 2002 Army Research Laboratory technical report, and a 2003 article in the journal Composite Structures, titled “Nonlinear Dynamic Behavior of Parachute Static Lines.”

These accomplishments demonstrate Millette’s engineering prowess and attention to detail – skills he utilized to make Army airborne operations safer.

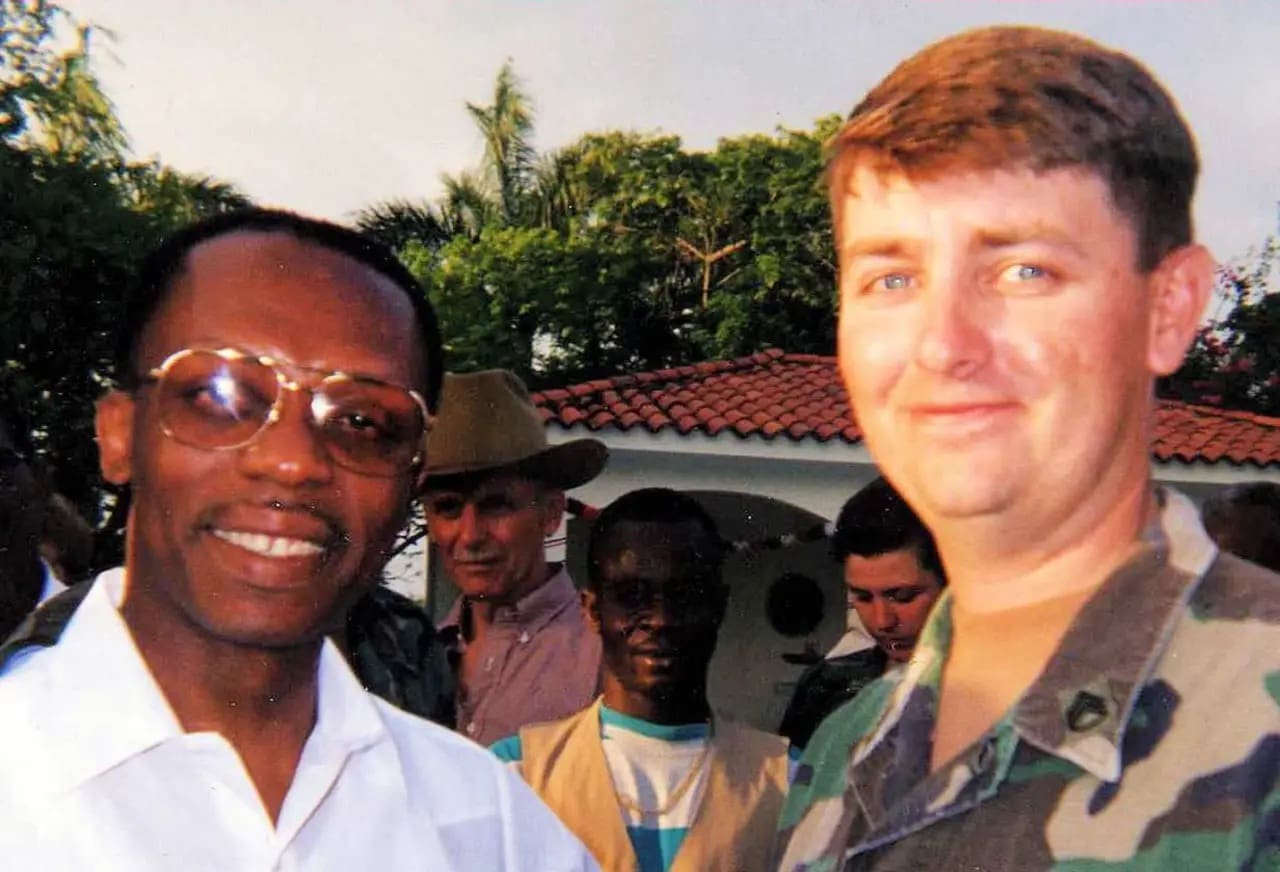

During this time, Millette continued to serve in uniform as an Army officer as both a combat engineer and civil affairs officer, deploying multiple times to hot spots around the world in support of military operations, including Operation Desert Storm, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Joint Task Force Horn of Africa, or JTFHOA, in Djibouti.

“Bill was a great team member, both in and out of uniform,” said Soldier Center’s Aerial Delivery Division Chief Mike Henry. “He had several tours of duty in uniform and always returned to Natick ready to jump back in to support the Soldier in his civilian role.”

After his deployment to Africa, Millette returned to ADEST and was selected to participate in the Naval Postgraduate School Master of Science in Systems Engineering distance learning program, which he completed in 2015, the same year he completed his military service and entered the Retired Reserve.

“Bill dedicated his career to being and supporting the professional Soldier,” said Henry. “Over the course of his career, he designed and analyzed numerous pieces of aerial delivery equipment, always to ensure the Soldier had the safest, most capable tools to conduct their missions.”

“His knowledge and experience will be sincerely missed,” Henry added.

Mahon’s military service reads like a checklist of qualifications for his future civilian job. As a Soldier, he became intimately familiar with the existing T-10 Parachute, and from then on, he would learn all things parachute.

Enlisting in 1969 during the height of the Vietnam War, Mahon served in a variety of airdrop-related jobs, including as a parachute packer, parachute repairman, parachute training instructor, sling load instructor, parachute maintenance technician, and parachute rigger – jobs that laid a solid foundation of technical expertise.

His last assignment in uniform brought him to the U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research Development and Engineering Center (now called DEVCOM Soldier Center), where he served as a military liaison and senior parachute rigger. In November of 1999, Mahon retired from active duty as a highly decorated Chief Warrant Officer 4 with extensive experience.

After a few months working as a DOD contractor, Mahon was hired in March 2000 as an Army civilian in the role of Senior Airdrop Equipment Specialist for ADEST, where he also returned to jump status, using his military experience to provide guidance to personnel developing airdrop and aerial delivery equipment for Soldiers until his retirement in 2024.

At ADEST, Mahon led numerous field-failure investigations and was an active participant in the Materiel Review Board, The Joint Technical Airdrop Group, and numerous other DoD-level aerial delivery working groups, committees, and projects.

“John was a corner stone in the aerial delivery community for decades, from his active-duty career to his civilian service,” said Henry. “He had the knowledge and experience to quickly respond to any request the field had of him, often resulting in TDY at a moment’s notice. He possessed competencies that only exist after one has spent decades in the career field.”

Sharing and passing on his knowledge was a common theme expressed by former coworkers and teammates.

“He also worked diligently in his time leading up to departure to distribute his hard-learned lessons to others and will leave a lasting impact on both the civilian and military aerial delivery community,” said Henry.

“John had a unique ability to help his fellow engineers and scientists understand how airdrop worked,” said William Ricci, a senior research engineer at Soldier Center and Mahon’s former ADEST teammate.

While serving in his civilian capacity at Soldier Center, Mahon led the effort to rapidly field the Low- Cost Low-Altitude (LCLA) cargo resupply system for Soldiers serving in Afghanistan, where he deployed to help train operators to use the system. The LCLA went on to successfully execute uncountable small-unit resupply missions for Soldiers on the ground.

“Throughout my years in service, I was continuously involved with safety investigations, developing rigging procedures, or providing malfunction analysis to all branches of the services,” said Mahon. “I believe some of my analysis contributed to identifying training equipment shortfalls, training enhancements needed and overall reducing risks to the individual paratrooper.”

During his career, Mahon received numerous commendation awards and top honors for his work, most notably, his inductions into the U.S. Army Warrant Officer Hall of Fame, the U.S Army Parachute Riggers Hall of Fame, and the U.S. Army Quartermaster Hall of Fame. Feats only a relatively few other Soldiers have accomplished in the history of the Army.

Mahon retired with an incredibly distinguished professional career. He is highly revered for his technical expertise, his dedication to protecting Soldiers, and his fascinating, funny stories.

“John and Bill played major roles in establishing Soldier Center’s reputation as experts in the development and evaluation of aerial delivery technology,” said Doug Tamilio, director of DEVCOM Soldier Center. “Their careers, both in uniform and as civilians — including investigating accidents caused by personnel parachute malfunctions — improved the safety of DoD airborne operations and advanced the aerial sustainment of warfighters for generations to come.”

“We honor their contributions to the Army aerial delivery community, and we will greatly miss their presence at Soldier Center,” said Tamilio.

LAST JUMP

One of the reasons Mahon and Millette were so proficient at their jobs was that they remained on active jump status throughout their civilian careers, giving them continued personal experience using the same equipment that they helped develop and improve for Soldiers, often with and alongside them.

Their extensive experience using the personnel airdrop equipment over the course of their military and civilian careers provided invaluable direct insight and served as an essential tool in shaping design and performance feedback, and honed their expertise, which they passionately applied to protecting Soldiers.

It was also simply a fun part of their jobs. Not just for the thrill and challenge of parachute jumping itself, which they clearly enjoyed, but for remaining a part of the Army airborne community and the comradery of jumping with coworkers on the Natick Parachute Team, which is comprised of both military and civilian jump-qualified employees working on the NSSC installation.

“I’ve been very fortunate. I’ve had no major jump incidents,” said Mahon. “But that experience, and having lived those scenarios, is invaluable to the work that we do and for understanding [parachute] deployments. It reinforces the idea that we need to make sure the equipment we make is safe, reliable and capable.”

So how did they end their decades of being on active jump status? With one more jump, naturally.

Two weeks before their retirement ceremony, Mahon and Millette both completed their last official military static line parachute jump for the Army during combined airborne operations training between the Natick Parachute Team, and the Rhode Island Army National Guard on June 7 at Flintstone Drop Zone in West Greenwich, Rhode Island.

There, Mahon capped his combined military and civilian 55-year airborne career with his 1159th and final Army jump during the training event, while Millette’s final was his 110th.

They were the first jumpers out of the aircraft, the first to land, and then celebrated by their fellow jumpers as they came off the drop zone.

There was no fanfare, no special awards. Just fellow jumpers, Soldiers, and coworkers waiting to congratulate them on the last official jump of their amazing careers, and the combined 116 years they carried with them.

By Jeff Sisto, DEVCOM Soldier Center Public Affairs