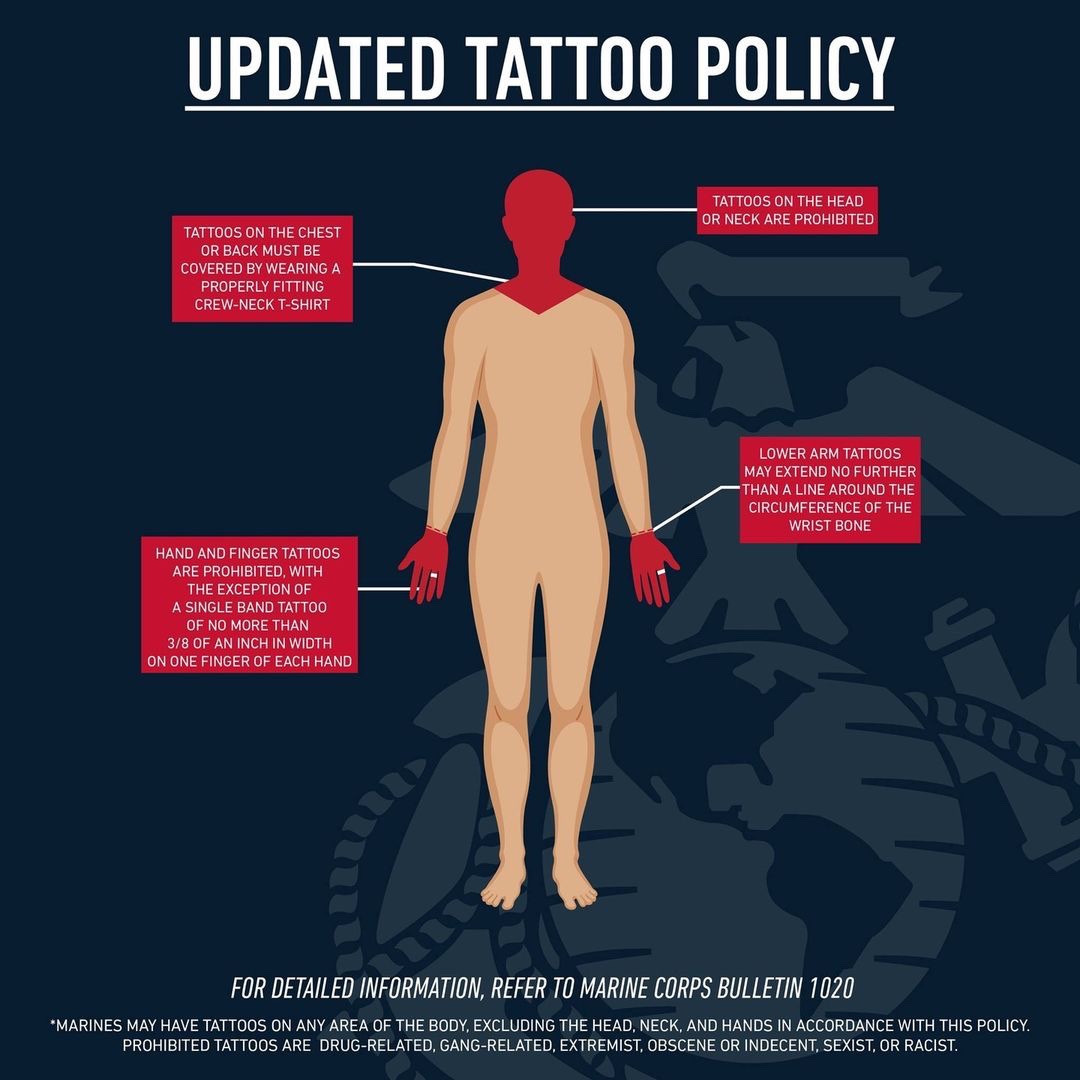

Today, the Commandant of the Marine Corps has approved changes to the Marine Corps policy regulating tattoos. Key policy changes can be found in Marine Corps Bulletin 1020, uploaded here: go.usa.gov/xeaHF.

Today, the Commandant of the Marine Corps has approved changes to the Marine Corps policy regulating tattoos. Key policy changes can be found in Marine Corps Bulletin 1020, uploaded here: go.usa.gov/xeaHF.

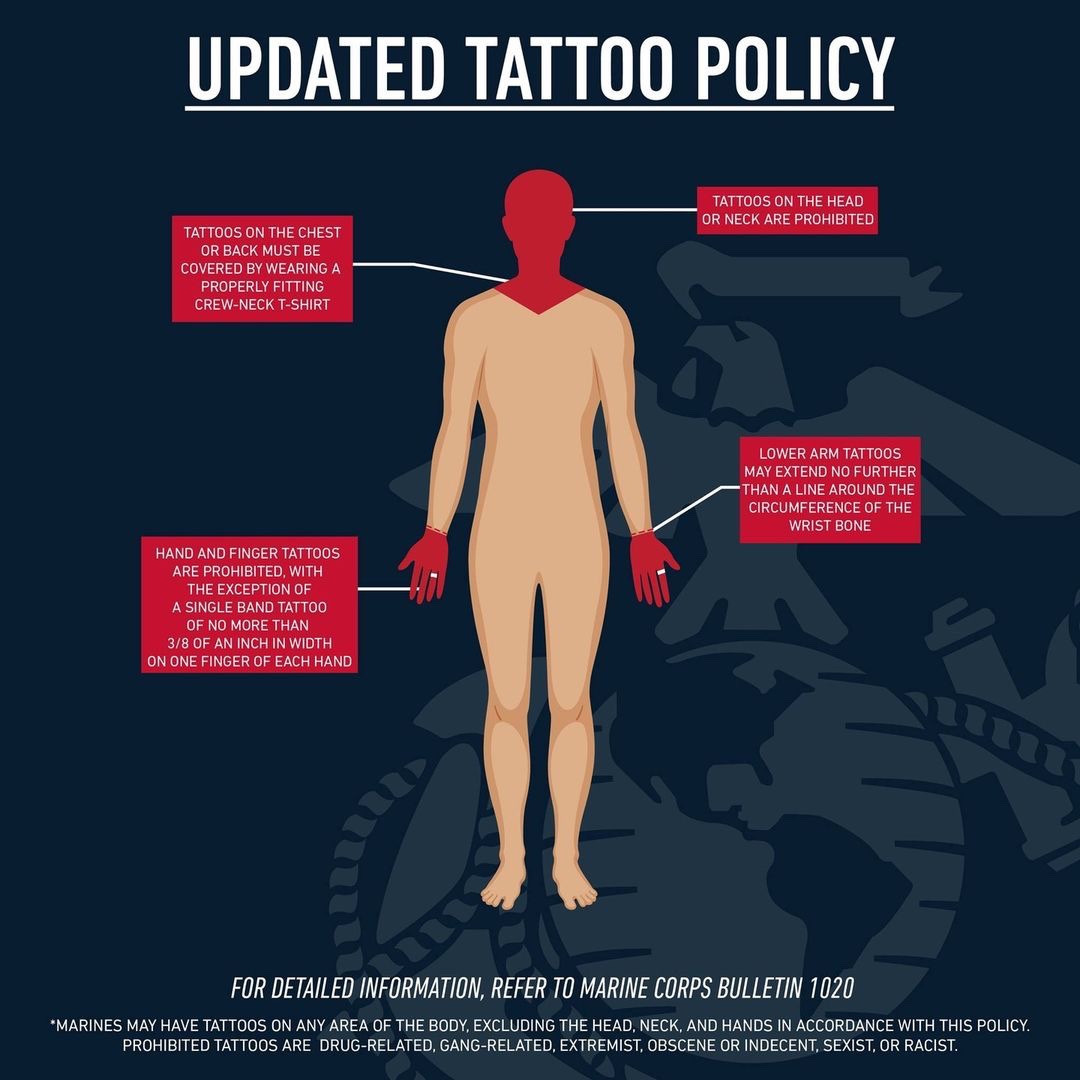

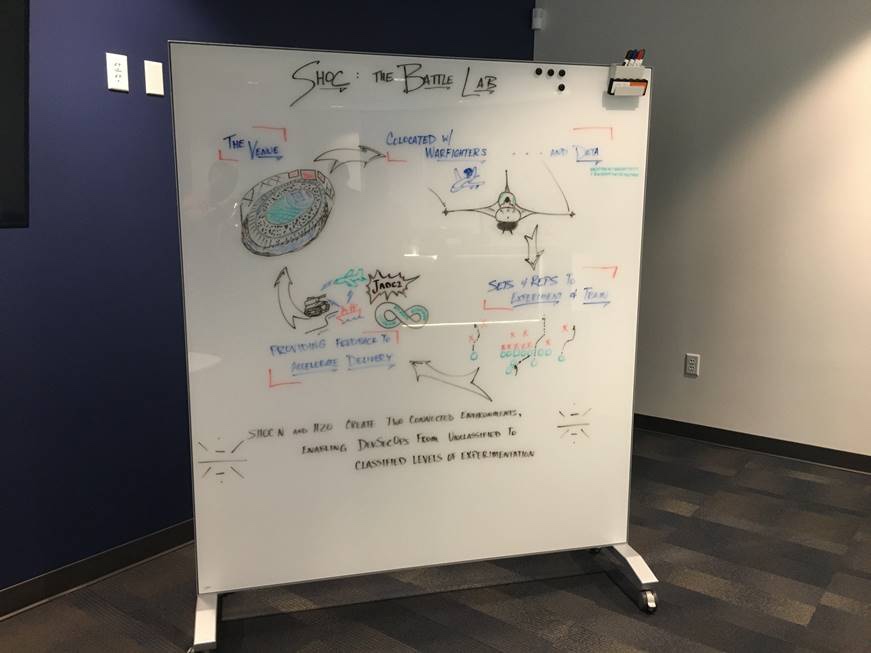

The Multi-Domain Warfare Officer Initial Skills Training class 21B visited the 805th Combat Training Squadron’s Shadow Operations Center at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, also known as the ShOC-N, to observe the experimentation and incubation of new command and control technologies and development of C2 tactics, techniques, and procedures, Sept. 23-24.

Nellis AFB, Nevada, was the second of a four-leg trip for the Multi-Domain Warfare Officer, or 13O, students traveling to geographic and functional operations centers. The class’ destinations included the Combined Space Operations Center, or CSpOC; Space Delta 5, at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, the 612th Air Operations Center, Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona, and the 616th Operations Center at Joint Base San Antonio, Texas.

The 19 students of class 21B also toured ShOC-N’s downtown Las Vegas site, the Howard Hughes Operations, or H2O, facility. AFWERX briefed the 13Os about their latest efforts to discover innovative opportunities within industry and Department of Defense partners for delivering tangible capabilities to warfighters.

In 2019, the Joint Chiefs of Staff tasked the ShOC-N to become the U.S. Air Force’s Joint All-Domain Command and Control, or JADC2, Battlelab. Part of this task as recently evolved to make the ShOC-N the primary location for data gathering and sharing to further enable the U.S. Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System Battlelab ecosystem.

The 13O students’ Nellis training concluded with peer adversary Integrated Air Defense Systems and threat emulation briefings from the 547th Intelligence and 57th Information Aggressor Squadrons, respectively.

“Our adversaries’ threats and capabilities are real; within months, these 13Os are going to be the multi-domain operational planning experts that senior leaders look to for COAs [courses of action] on what to do, how to do it, the risks involved, and how to effectively mitigate those risks,” according to Lt. Col. Joe “DACO” Thompson, 705th Training Squadron operational warfare training flight director.

Thompson continued, “13Os can’t provide COAs without knowing who is doing what and where. A lot of ‘what and where’ is on the ground at Nellis, but there’s also a lot of ‘what and where’ within our sister services’ components and non-air domains. We teach them that, and this TDY [temporary duty] reinforces that critical 13O mindset.”

The 705th Training Squadron’s Multi-Domain Warfare Officer Initial Skills Training course is taught at Hurlburt Field, Florida. The 13O course deliberately develops a multidisciplinary force skilled in operational art and design across all domains. 13O graduates will be operational planners versed in the joint planning process, representing the U.S. Air Force’s equity in the joint planning environment, affecting Joint All-Domain Command and Control, or JADC2, and Joint All-Domain Operations in a high-end, near-peer conflict.

To learn more about 13O training and the Multi-Domain Warfare Officer career field, visit the following websites: intelshare.intelink.gov/sites/C2/13O/SitePages/Home and www.milsuite.mil/book/groups/13O.

The 705th TRS reports to the 505th Test and Training Group and 505th Command and Control Wing, both are headquartered at Hurlburt Field, Florida.

Deb Henley

505th Command and Control Wing Public Affairs

The Multi-Domain Warfare Officer Initial Skills Training class 21B visited the U.S. Space Command’s Combined Force Space Component Command at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, to observe real-time operations, Sept. 20-21.

Vandenberg SFB was the first of a four-leg trip for the Multi-Domain Warfare Officer, or 13O, students traveling to geographic and functional operations centers. The 13Os also traveled to the Shadow Operations Center – Nellis, or ShOC-N, at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, 612th Air Operations Center, Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona, and the 616th Operations Center at Joint Base San Antonio, Texas.

The 19 students of class 21B were able to tour and observe real-time operations at the Combined Space Operations Center. The CSpOC’s mission is to execute operational command and control of space forces to achieve theater and global objectives.

The 13O students were also given the opportunity to talk to several senior U.S. Space Force leadership, including CFSCC Commander Maj. Gen. DeAnna Burt. Discussions focused on inter-service interactions and daily planning challenges facing CSpOC Guardians such as command relationships, authorities, and the development of C2 strategies as USSPACECOM components are reorganized, and new components become operational.

Maj. Gen. Burt stressed the significant role local 13Os have and continue to play in overcoming these challenges, bringing all these efforts together into one integrated plan.

“Observing real-time CSpOC operations allowed our students to witness first-hand many of the space capabilities, threats, limitations, and planning considerations previously covered in our classroom academics,” said Lt. Col. Ernie “Bert” Chen, 705th Training Squadron deputy director of operational warfare training, Hurlburt Field, Florida.

The Multi-Domain Warfare Officer course is taught by the 705th Training Squadron whose mission is to provide advanced operational level multi-domain C2 training and education for joint and coalition senior leaders and equip air operations center warfighters through tactics development.

To learn more about 13O training and the Multi-Domain Warfare Officer career field, visit the following websites: intelshare.intelink.gov/sites/C2/13O/SitePages/Home and www.milsuite.mil/book/groups/13O.

The 705th TRS reports to the 505th Test and Training Group and 505th Command and Control Wing, both are headquartered at Hurlburt Field, Florida.

OKINAWA, Japan —

U.S. Marines across Okinawa participated in the new Annual Rifle Qualification from Oct. 4-8. This consisted of a three-day course of fire that tests Marines’ marksmanship skills in a dynamic-shooting environment.

The intent of ARQ is to provide an enhanced combat centric evaluation that uses a lethality based scoring system with more realistic standards. Shooters utilize artificial support to engage moving targets both while on foot and remaining stationary.

Day one

The day began with heightened nerves and rigid composures. However, not for battlesight zero, but for what was to occur in the days to come. These Marines were the first on the island to shoot the new ARQ course of fire.

“When I first heard about the range changing, I was concerned,” said Sgt. Morelia Capuchino Diaz, a food service specialist with Camp Courtney Mess Hall, Combat Logistics Regiment 37. “I wasn’t sure what to expect.”

She expressed that she came to the range really nervous. She knew the course of fire was going to be more difficult and physically demanding due to moving while shooting in full gear. Overall, it was unfamiliar for everyone and that meant all of the Marines needed to work side-by-side to conduct the range in a timely and proper manner.

What changed?

The Marines still shoot at the 500, 300, 200, 25 and 15-yard line, however, major adjustments were made. A few changes include: static engagement of stationary and moving targets, barricades for weapon stabilization, on the move engagements of static targets, and an adjusted scoring system.

“It’s more combat oriented and combat effective to train this way,” said Staff Sgt. Kaleb Bill, a marksmanship school house staff noncommissioned officer with Marine Corps Installations Pacific, Marine Corps Base Camp Butler’s Formal Marksmanship Training Center. “It also judges Marines based on their lethality as opposed to precision style shooting.”

Shooting this new course of fire allows Marines to make their own judgements and think critically. In a combat situation, while the fundamentals still apply, they may need to determine how to utilize the materials they are given by themselves.

The preparatory period of instruction has also been adjusted with the new rifle qualification. Grass week, a scheduled time Marines use to practice marksmanship fundamentals, is now a command dictated event. There is no longer a formal requirement to attend a grass week. However, it is still strongly encouraged by range personnel to participate in these preparatory classes.

“It’s more combat oriented and combat effective to train this way.”

Staff Sgt. Kaleb Bill

Marksmanship school house SNCO

“It is highly, highly recommended that you attend,” said Bill. “I strongly encourage all commanders to enforce grass week to ultimately prepare the Marines for the new ARQ. I can’t stress it enough. It may not be a requirement, but conduct the grass week, the preparatory training and issue out range books to your Marines.”

Day two

The second day of the range was the first time the Marines officially shot the new rifle qualification course of fire. Each shooter had an opportunity to run through the course of fire and ask the coaches as many questions as they needed. It was communicated to them to use the time allotted to completely understand the drills and ask for help.

As the day progressed, Capuchino expressed that she started to understand the course of fire a little better, however, there was still a clear adjustment period to work through.

“At first I was a little off because it was something new, especially the failure to stop – going from the pelvis to now the head and also applying a lot of individual headshots,” she said. “I felt way more confident once I realized we had a lot of opportunities for each drill to get at least one destroy for each.”

A ‘destroy’ is a zone on a target where the shots must impact to be counted. Additionally, failure to stop drill used to consist of shooting into the chest and pelvis zone. However, now the drill has transitioned to chest and head shots only.

The hardest part was time management during the second day, says Capuchino. The Marines were still learning and had not fully grasped the time hacks and how long it would take to shoot which she expresses was very stressful.

Day three: Prequalification

“The third day I was more confident, but was still learning the course of fire,” said Capuchino. “Even though it was a little intimidating, the challenge of it made me want to succeed. It is something new and as Marines say, we need to adapt and overcome.”

Capuchino explains that she’s always enjoyed a challenge, especially as a competitive person. With a wide smile, she continues to say she and her friends have always tried to compete and beat each other’s rifle scores. Fortunately for her, Capuchino has been a strong shooter since recruit training and sees this range as an opportunity to challenge herself and mentor her junior Marines about the new rifle qualification.

“My favorite part about the range is you get to make decisions on your own,” said Capuchino. “Even though it’s a different range, we still use the fundamentals we were previously taught. Now it’s just more high-tempo and you have to think fast. Like during the barricade drills, you have eight seconds to get a controlled pair. So you’re standing and you have seconds to get into position, aim right, take those rounds and get up.”

Day four

Day four was originally slated for qualification day, however, due to inclement weather the Marines were unable to finish and had to continue shooting on the fifth day.

Despite shooting through rain and wind, Capuchino was doing better than ever.

“At this point I already knew where all my holds were at and all I had to do was get used to applying all the fundamentals faster,” she said. “I was nervous, but I ended up getting all three ‘yes’ for qual due to good coaching and sufficient.”

While shooting at the 25 and 15-yard line, a ‘yes’ means that the Marine gets all of their shots for that drill in the destroy zone.

Day five: Qualification

“The last day I was confident and knew what to expect,” she said. “I was ready to shoot my best, and I ended up getting higher than I expected.”

The range was finally complete and Capuchino finished with an expert score. Achieving this score was a significant accomplishment to her because of her initial intimidation of the new course and the values she holds of leading from the front with an expert score.

“Especially now as you get higher up in rank, you need to set the example for your junior Marines,” she said. “I try to do well so my Marines see that I am trying, and then hopefully that helps instill that motivation to continue to improve themselves despite a challenge. As a leader, it’s now our role to tell them our mistakes and give advice on what they should and shouldn’t do so it can help set them up for success.”

Despite the inclement weather, success reached Capuchino and other shooters on the range. Every Marine finished with a qualifying score, which to range staffs’ knowledge, this was the first time there were no unqualified Marines.

“After shooting this new ARQ, I can tell that I like this range, and it is better than the last,” said Capuchino. “I prefer this new course of fire because it goes back to that combat mindset and is combat oriented. As you are shooting, take into consideration that the chances of going into combat are always there. It’s important to take what we learn here and apply that knowledge if ever needed. Remember, train as you fight.”

By Cpl Karis Mattingly

The General Order is always: To maintain strict but not pettifogging discipline. — Lazare Carnot

With regard to military discipline, I may safely say that no such thing existed in the Continental Army. — Friedrich Wilhelm Von Steuben

This article is all about discipline. Although, I am going to exclusively use drug and alcohol-related incidents as the vehicle to make the points I want to emphasize. During my service, I saw many a soldier’s career, marriage, finances, and life, damaged by the abuse of legal and illegal drugs including alcohol. I do not want to minimize that sad fact. However, I also saw that, in those and many other instances, presumably well-meaning efforts by leaders to discipline troubled soldiers actually served to exacerbate the problem rather than mitigate it. Eliminating soldiers instead of rehabilitating them. In many cases, this was because of a common misunderstanding of the nature of “military discipline” itself. Understand this. Leadership is the only engine that can move an organization forward, but discipline is the fuel that makes it go.

A unit that has poor discipline is simply running on fumes and needs to be refilled by leadership. Even good units need to be occasionally topped off. Many novice leaders – and some who are just not very good at leading – assume that they have a duty to impose discipline on soldiers. They think of discipline as fundamentally a weapon of punishment. A proverbial Sword of Damocles they, by virtue of their rank, can wield as they see fit against their soldiers. In their minds, it is necessary – and their prerogative – to shove discipline down the individual troopers’ throats; the sooner and the harsher the better. Of course, that misguided leadership style also assumes that soldiers are impervious to any form of discipline that is not forced upon them. Wrong! Good leaders do not impose discipline. Rather, good leaders know that if they resolutely demand discipline of their unit the soldiers will deliver. Sua Sponte. Good leaders settle for nothing less.

I joined an Army that, in my opinion, practiced a better disciplinary model than I saw in the last half of my career. In the late 1970s, Article 15s (ART 15) (Non-Judicial Punishment) were given out generously. Indeed, it was something of a tradition for any new CSM coming into an Infantry Battalion to tell all the assembled NCOs how many he had managed to accumulate. The most I ever personally heard was eight. The point was not to celebrate how much of a trouble maker he had been in his younger days; but rather to emphasize that he had made the most of his opportunity to “soldier out of” those early mistakes and still gone on to be successful. In those days, punishment came almost exclusively from the Company Commander and was swift. The process was also transparent. An ART 15 was required by regulation to be posted on the Company Bulletin Board for seven days and then kept on file in the Company Orderly Room until the soldier left the unit. At that time the paperwork was destroyed.

That is right. Destroyed. Certainly, these tools were punitive and served to punish with penalties like restriction to barracks, extra duty, monetary fines, removal from promotion lists, and even loss of rank. If a Company Commander wanted more severe punishment, he could refer it to Battalion for a Field Grade ART 15. That rarely happened. Company Commanders and First Sergeants were more than capable of handling these kinds of minor indiscipline problems themselves. In my experience, most Battalion Commanders preferred it that way as well. Sure, an ART 15 also “sent the right message” to the soldier receiving it as well as all the other soldiers in the unit. A little public shame never hurts anyone who has earned it. But, here is the most important part, the ART 15 always came with the equally sure promise of the opportunity for redemption!

Sometime in the late 1980s that began to change. There was legitimate concern that indiscipline numbers were too high and needed to be addressed. So, as is often the case, in response to a perceived crisis the Army made a poor leadership decision. The institution decided that stricter discipline needed to be imposed – the sooner and harsher the better. Over time, any and all issues of indiscipline were pulled up to the Battalion Commanders’ desk and Field Grade levels of punishment. That was an unnecessary escalation in the vast majority of cases. Automation had a negative impact as well. New reporting requirements meant that an ART 15 was now being reported immediately to Department of the Army where it went into a soldier’s centrally maintained “permanent record” – never to be destroyed or forgiven. In short order, Company level officers were effectively stripped of that tool altogether. More than that, as Battalion Commanders realized that a single ART 15 was now a career killer, they too started to use it less frequently.

Oddly enough, the more the ART 15 is used, the more effective a tool it is. Used infrequently it was entirely negative and no longer had the positive impacts I had seen just a few years before. I have mentioned in a couple of earlier pieces that I almost got an ART 15 in Germany but got a “rehabilitative” transfer instead. That would have been my third ART 15, not my first. I had two before that. One at Fort Polk, LA when I was in Infantry Basic Training for failing to follow an order. I got five days in CCF for that one. I think CCF stood for “Commanders Correctional Facility,” but everyone called it “Charlie’s Chicken Farm” for some reason. We still had one at Fort Lewis when I was there in 1978-80. I sent a couple of guys to that one. It helped them. All in all, it was a pretty good idea that left no permanent marks.

CCF was not much different from Basic Training. A day consisted of Physical Training, Barracks Inspections, Drill and Ceremonies, and Road Marches – but with less time between events and even less sleep. I went in right after my Company graduated Basic and got out just in time to rejoin them in a different Company in the same Training Battalion for Infantry AIT. My training leadership set it up that way. When I left, some of the CCF Cadre shook my hand and wished me luck. A couple told me that they had been alumni as well. It helped focus me. I got my second ART 15 shortly after getting to Germany. Missing formation twice. Each workday morning the Charge of Quarters (CQ) would go up and down the hallways rapping once on each door to wake everyone up. I was in a two-man room but my roommate was at some school. I did not yet have enough self-discipline to get myself up on time.

I deserved both ART 15s, and – for the most part – they served their re-training purpose and were then officially forgotten. I submit, that is a very good way of doing business. When I was interviewed some years later for a Top-Secret Clearance, the Investigator asked me if I had ever had any disciplinary actions? I told him “Yes, two.” He said, “well, they are not in your record?” I replied, “That was the point.” In that case, had the ART 15s been in my record, I expect that I would have been granted the clearance anyway. The infractions were minor and from many years earlier. However, I likely could not have gotten into OCS if those two blemishes had been on my permanent record and if I had applied in the 90s rather than the early 80s. In fact, I probably would have been denied promotion and forced out before I might have ever applied. So much for redemption.

I witnessed or participated in countless episodes of drug and alcohol-powered nonsense. I am just going to share a couple to illustrate what I consider the more right or least wrong ways to approach and handle these leadership and discipline challenges. I will come back to drugs, but I want to start with my most extreme personal experience with alcohol. We drank a lot in Germany in the 1970s. That is what we thought soldiers did – and our Sergeants generally set that example. Still, I was observant enough to know that some of my compatriots were drunks more than they were social drinkers.

When I transferred to the 3rd Aviation Battalion’s Pathfinder Detachment as a Specialist (E-4) I was in a barracks full of helicopter Crew Chiefs. We got along pretty well. However, shortly after I got there, one guy decided he wanted to have a drinking contest with me. I had no doubt that he was a heavier drinker than I was, but I was not smart enough to just say no. It was a matter of pride. We were in his room with a half-dozen “witnesses” to judge the winner and loser. We sat on two bunks facing each other. He supplied the booze. A gallon jug of Jim Beam as I recall. One of us would take a slug and then pass it to the other. We continued this routine for about 20 minutes and had consumed just shy of half the bottle. Neither of us had moved from the bunks. We were slowing down, but I was feeling good. I felt like I was handling the alcohol quite well. I could see that his eyes were glazing over. I thought I was winning. Of course, he could see my eyes and he thought the same thing!

I remember getting to the 20-minute mark clearly. I do not remember anything after that. Here is the story that was relayed to me the next afternoon – some 14 hours later – when I regained consciousness. We continued to drink for about 10 more minutes. Then my opponent threw up on his bunk. So, the judges decided I won on a technicality. Thankfully, my stomach was smarter than I was. While he was purging on his bed, I actually got out to the hallway before I began to projectile vomit. The witnesses were impressed that I was able to lean against one wall and “paint” the opposite wall some 8 feet away. I made it to the latrine bay, where, I am told, I stood in one place and “hosed down” all six sinks on the wall and the first two toilets on the far side “Exorcist” style. It was reportedly quite the show. Then, I pushed past the gawkers, went to my room, and crashed.

I was told that the CQ tried valiantly to wake me so that I could “clean up my mess.” That did not work. He might have left it for me, except the odor was so foul he had to go ahead and order his runner to clean the hallway and latrine immediately. That runner held a grudge against me for a long time. I slept through almost all of the inevitable hangover. In truth, I regurgitated almost all of the alcohol I consumed before very much of it even had a chance to get into my system. I was lucky. Was I disciplined for this misadventure? Absolutely not. I had broken no laws or violated any regulations. Since the MPs were not called and nobody went to the hospital, I doubt if the CQ even made a note of it in his Log. Just a typical Friday night. On the “plus” side I had now made a name for myself, as young men often do when trying to impress other immature youngsters, by doing something especially stupid and surviving.

To be clear, that escapade was idiocy incarnate. Considering the very real possibility of alcohol poisoning, it was damn near suicidal. Did I ever do anything close to that again? No. Did I stop drinking altogether? I certainly did not. Let me elaborate a little more about the relationship between the Army and alcohol back then. For the Army, alcohol consumption was a fully sanctioned and highly traditional form of self-medication. I mentioned in the first paragraph some of the negative consequences of alcohol abuse. Alcohol is much like fire. Used properly and with reasonable control measures, fire is an invaluable tool. Used improperly or unsafely it can destroy you and everything you love. I eventually figured out that if one gives alcohol the same respect they give fire, it is possible to maximize the positive and minimize the negatives – and not get burned in the process.

I am sure that sounds like a completely mixed message. Allow me to elaborate. Alcohol has been known as a valuable “social lubricant” for millennia. It can still serve that positive purpose. For many years, the Army had a tiered club system. Even small posts had an Officer Club, NCO Club, and Enlisted Clubs. These started dying in the late 80s when those newer indiscipline reporting policies I mentioned started to become codified. I was in the 82nd Airborne Division for much of the 80s and Fort Bragg had a thriving Club system in those days. On Fridays, after weapons and gear had been cleaned and turned in, the Battalion Commander would issue an “Officers Call” at the O-Club. The CSM would have his NCO Call and the Enlisted Soldiers would make their way to the Enlisted Club to drink together. It was an invaluable team building exercise and gave everyone a sanctioned way to let off steam in a safe non-attribution environment. Unless specifically invited, Officers did not go to the NCO Club nor did the NCOs go to the Enlisted Club. Everybody had their space. And, unless the MPs or the Medics had to intervene, what happened at the Clubs stayed at the clubs.

There is an old saying that “if you get two privates together, they will act like privates; and if you get two Colonels together, they will act like privates!” That saying is true and, again if used judiciously, is a healthy concept both for the individuals and for units. When we killed the Club system, we lost all of that goodness. We did not change any drinking habits. All we did is push people off post where they no longer had a ready option to drink with their teammates. As a side note, on Bragg, peripheral on post drinking establishments like the Rod & Gun Club or the Green Beret Club held the line for a few more years but eventually suffered the same fate as the larger Clubs. People became more and more hesitant to drink on post at all. That is just not good for unit cohesion or – ultimately – for unit discipline.

To be fair, there was one area where change had a more constructive effect. That was in reducing DUIs. Way back when, a DUI off post was something between the individual and civilian authorities. I never had a DUI myself, but got close a time or two. I knew people who had 3 or 4 of the off-post variety. For a time, the Army addressed DUIs on post harshly – often with UCMJ action – and ignored the rest. That was an obviously arbitrary and unfair distinction. For the record, I have no problem with keeping intoxicated folks from getting behind a wheel and risking their own lives and others. We all have a vested interest in keeping our teammates alive.

I mentioned that most Battalion Commanders (BCs) became reluctant to use their ART 15 authorities. Most but not all. As we got into the 90s, some Commanders found that they were viewed favorably by Higher HQs if they had bigger ART 15 numbers. It implied that they were aggressively “going after” indiscipline and, I suppose, made them look “hard.” As a Special Forces Company Commander, I had a problem with that. First, even though I was a Major – and therefore a “Field Grade” office myself – I had no Non-Judicial Punishment authority at all. Everything had been consolidated at Battalion. Not that I needed it a lot, but I considered it a tool I should have available to me. Unfortunately, mine was the minority opinion.

That arrangement did cause me a few unnecessary problems over the years. In one case, I had most of my company at Fort Bliss. During off duty time, drinking was certainly allowed. One night, members of an ODA put an inebriated teammate in a cab to send him back to the facility where we were staying. Somehow the directions got garbled and since the soldier was passed out the cabbie brought him to the MP station on Bliss. The MPs had our emergency contact information and called us to pick him up. No big deal. My SGM made the extraction shortly after we were notified. However, without any malign intent, the MPs apparently submitted a routine report of the “incident” and that got to Bragg. The next thing I know, I am getting a call from my BC that he wants me to refer “the case” to him for a Battalion level ART 15. I was flabbergasted. I told the BC there was no “case” and that the soldier had committed no crimes or violated any regulations and I was NOT about to refer anything to Battalion.

That confused the BC. He then wanted to know how I was going to discipline said soldier. I repeated “no crime, no violation” and told him that I was not contemplating any action against that soldier. That confused him more but effectively ended our conversation. For obvious reasons, I did not share with the BC that I intended to apply my own form of disciplinary action on a number of others involved. I had the ODA assembled the next morning and proceeded to chew their collective rear ends for not covering their incapacitated teammate’s 6 the way they should have. Before that, I met with the Team Leader and the Team Sergeant and gave them both Letters of Reprimand (LORs) for the same reason. I told them that I had written the two letters personally and that I had no paper or digital copies. Furthermore, now that I had given them the message that they had screwed up, I intended to forget about the incident. I told them they could do whatever they wanted with the letters. However, I suggested they frame them and hang them on a wall somewhere to remind themselves of the time they let their team down.

I did not invent it, but I used that “trick of the leadership trade” more than once. I do not know if those letters helped much, but they did not hurt. The folks I gave these sorts of reprimands to went on to have very successful careers and I am proud of them. Ok, what about drugs? Last time I mentioned that two soldiers in my Infantry Company overdosed on Heroin and died in the barracks in Germany in the first few weeks I was there. I admit that scared me. From watching “That 70s Show,” I now know that marijuana was readily available in the 1970s – at least in Wisconsin. I went to High School in Ohio and I never saw it. Underage drinking? Absolutely! That was the extent of my experience so it is fair to say that when I joined the Army, I was completely naïve about drugs.

Besides Heroin, LSD was available in some quantities in Germany. Probably some other “hard drugs” as well. I stayed well away from any of that shit. But mostly it was Hashish out of Turkey. We had a good number of hash smokers. Now, I am not going to tell you that I never caved to peer pressure and experimented by taking a few tokes – or more – on a hash pipe. I did. I did not care for it. If you saw “Platoon” you know that the uncool “Lifers” drank, and the “cool kids” like Charlie Sheen’s character smoked. I found out pretty quick that I did not fit in – or want to fit in – with the smokers and much preferred the drinkers – even if they were the dreaded “lifers.”

To be sure, both sides swore they hated the Army with a passion. However, drinkers partied out in the open. They would open the doors of their rooms and let anyone passing by come in and share. Their self-medication routine was more of that team-building variety I talked about earlier. The smokers hid in their rooms with their windows open to let out the smoke bitching endless about how their recruiter lied to them. It was unappealing and depressing. It turned out that the people I respected – the NCOs – drank. So, I made a point to hang out and drink as much as I could with them instead. It certainly turned out for the best.

One last drug-related situation. When I was out at Camp Mackall, I had an NCO working for me who had been selected as the SWCS Instructor of the Year a few months before I got there. He was a SFC just short of 18 years in service. Then he came up hot on a piss test – cocaine. It turned out that he was in his late 30s and for his mid-life crisis he had gotten himself a 20-year-old college wife instead of a sports car or new pick-up truck. I never met her, but she was apparently a “party girl” and hot. Very hot. She allegedly liked to snort a couple of lines before sex. Eventually, she convinced him that it would “enhance the experience” if he did the same. I am not saying the girl led him astray; but, yea, she did. Any of us that own a penis know how easily that can happen.

I am not excusing his part in it. He was older and a senior NCO. He knew better. This was a cut and dried indiscipline case that would have gone above me no matter when it happened. However, he was one of mine and I wanted a say in his punishment. My BC at the time was hard over to drum him immediately out of the service with a “Less than Honorable” discharge. In fact, he wanted it expedited before the NCO reached the 18-year mark to ensure he would not be eligible for any retirement benefits. I considered that petty and unnecessarily vindictive – and told my BC so. I countered that the NCO had not been arrested, had not been charged with cocaine possession, and his previously exemplary duty performance had not ever been affected in any obvious way.

I argued that he should be busted to SSG and allowed to continue to serve his remaining two years and retire honorably at 20 in that grade. That seemed more appropriate to me. Moreover, I argued that it would set the right example for the unit if he were given the opportunity to “soldier out of” his mistake. My arguments fell on deaf ears. It did not matter much in the end. I advised the NCO that he could – and in my opinion should – fight the discharge. He declined to contest the action. He was embarrassed and ashamed and felt the need to martyr himself. I thought it was a waste and, frankly, unjust. He was not irredeemable!

I should also mention that every leader knows illicit drugs are not the only variety that are problematic. I know any number of soldiers – up to the 3-Star level – who have struggled mightily with the addictive secondary effects of uppers, downers, and pain pills, prescribed and freely supplied by the U.S. Military to service members. There is certainly a logical argument to be made for “zero tolerance” when it comes to the abuse of drugs, or alcohol, or any other case of indiscipline. Nevertheless, I do not find those arguments compelling. If we max out the punishment for everything, we are establishing the false equivalency that all indiscretions are of equal weight and severity. That is demonstrably not true. And we deny any possibility of redemption. Commanders have considerable discretion under UCMJ for a reason. We know full well that humans make mistakes. Sometimes egregious mistakes. Especially the young. Often drugs and alcohol contribute to those errors in judgment. If we are being honest, we also know that most of us have only barely dodged some of those career-ending circumstances ourselves.

Military discipline is not principally about punishing a soldier or giving a Commander the chance to put another notch as a hardass on his record. Instead, military discipline should be primarily about what is good for the unit, the Army, and ultimately the Nation. Sure, if you find a truly irredeemable individual, by all means, cut that one away, ASAP. In my experience, there are very, very few soldiers who do not deserve a chance to “soldier out of” their immediate problems. Thankfully, some of that is still happening today. I know of one soldier who got himself a DUI on Fort Hood a couple of years ago. At first, it looked like his Chain of Command was going to throw him out of the Army unceremoniously. He got a last-minute reprieve, regrouped, came back strong, and pinned on his Sergeant’s stripes just a couple of months ago. He was given an opportunity for redemption and he made the most of it. I think that the Army would be well served to make that sort of thing the official standard again and push healthy disciplinary powers back down to the company level. And stop posting all ART 15s in a soldier’s permanent record while we are at it!

De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.

WASHINGTON, D.C.— The study and use of history is a critical tool in the Army profession. It helps to inform current decision making, inspires Soldiers to serve, and builds morale and esprit in units.

“History helps us learn from the past, see the present and be ready for the future” said General Paul E. Funk II, Commanding General of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). “You have to understand your historical roots to become an effective leader.”

At this year’s Association of the United States Army (AUSA) Annual Meeting from October 11-13 at the Washington Convention Center, the U.S. Army Center of Military History (CMH) will host a Kiosk promoting the value of history in the Army. Preparing Soldiers at all levels to be historically minded is a significant role for CMH, an organization within TRADOC.

The Executive Director of CMH, Charles R. Bowery, Jr. points out, “All ranks in the Army, from the most junior trainee to the Chief of Staff, benefit from historical awareness in different ways. Every Soldier should understand that they are serving something bigger than themselves.”

A true understanding of history goes well beyond simply knowing key dates and events. The lessons of history develop critical thinking skills in Soldiers as they understand the reason why and how events unfolded in the past and their connection to today. It develops a more informed use of actionable history in current staff planning and decision making.

According to Dr. Peter G. Knight, Chief of Field and International History Programs at CMH, “We frequently respond to requests for information about historical events to help develop viable courses of action for Army leaders.” Knight recommends all Soldiers can use existing programs within the Army to improve their historical perspective. “There are professional military education courses and leader developmental programs like staff rides that can hone critical thinking skills.”

Staff rides are a unique and persuasive method of teaching the lessons of the past to the present day leaders. They can bring events to life and provide a greater understanding of tactics, leadership, strategy, communications and the psychology of Soldiers in battle. The staff at CMH develop and lead staff rides for U.S. Army organizations and provide detailed staff ride pamphlets online for free downloads.

Beyond decision making, history is also a key part of many aspects of a Soldiers career from understanding the rich heritage of his or her unit to accessing VA benefits as they transition to civilian life. Knight says, “A unit history program not only helps build esprit de corps, but it helps ensure unit awards and unit campaign participation credit are up to date.”

History also builds morale and helps to inspire men and women to serve by providing examples of those who exemplify Army values. “It connects Soldiers to their unit through activations, lineage and honors, unit decorations, and unit heritage” Knight said.

Leader support for the Army History Program will improve the understanding of history and its essential application in all units. Key elements of the program include assigning unit history officers, including Command Historians as part of staff functions and the use of Military History Detachments. Knight says “If you ever asked your staff if a certain situation has happened before or how did we handle a situation in the past, then you need a unit historical program.”

Other ways to expand historical mindedness is accessing the publications and research resources on the CMH website. Bowery also points out that “The Chief of Staff’s professional reading list is the best place to start. CMH and Army University Press also have thousands of free publications that Soldiers can access.”

The value and benefits of using history in the Army are significant factors to the success of units and individual Soldiers careers. The Center of Military History is a valuable resource with multiple tools that are available to all Army units and personnel.

“The Center of Military History can do all sorts of things for a leader development program, they can provide staff rides, they can provide lessons learned, and they can be the historical reference you need.” GEN Funk said.

By Francis Reynolds

Additional Resources:

WASHINGTON – Three changes to the Army’s retention program are scheduled to take effect Oct. 1, as the Army looks to simplify aspects of the reenlistment process and give Soldiers more flexibility before their expiration term of service date.

A modification to the Career Status Program, formerly known as the Indefinite Reenlistment Program, an adjustment to the Reenlistment Opportunity Window, or ROW, and to one of the extensions will all take effect starting fiscal year 2022, said Sgt. Maj. Tobey J. Whitney, the Army’s senior career counselor.

“These changes are being made with the intent of increasing predictability for Soldiers and their families while also reducing turbulence within Army organizations,” Whitney said.

Career Status Program

Soldiers ranked E-6 and above and with 10 years or more of active service will now be eligible for the Career Status Program, reducing the time in service threshold from 12 years, Whitney said.

“We found through collected data that staff sergeant and above with more than 10 years of service were required to reenlist at least twice to make it to retirement,” Whitney said. “That doesn’t seem like a logical solution to keep Soldiers in the Army.”

The update to the CSP will not change any of the Army’s voluntary separation policies, which allow Soldiers to request a discharge or enter into the Career Intermission Program, he added.

Under CIP, Soldiers can take a break in service while receiving their benefits and a portion of their pay for up to three years, Army G-1 officials said earlier this year.

“We want to ensure that [qualified] Soldiers understand their eligibility for the Career Status Program,” Whitney said. “If Soldiers can just reenlist for an indefinite term of service, they can go and continue with their careers.”

ROW changes

The change to the ROW policy will give Soldiers 12 months before their ETS to review their reenlistment options and make a final decision, Whitney said.

“The ROW is currently set at 15 months, but we are changing it to 12 for two main reasons,” he said. “First, it is simple for Soldiers, leaders and families to understand when they are 365 days from their ETS.

Second, “the analytics over the past several years [show] that the vast majority of Soldiers wait until they are between eight to 11 months before they reenlist.”

The adjustment to the ROW extension would increase the minimum term length from 12 to 18 months, Whitney said.

The transition process can create a lot of turbulence in a Soldier’s life, he said, as well as impact their organization as they navigate the Soldier for Life program and finish their out-processing tasks.

As the Army continues to operate during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said the ROW extension change would remain a short-term retention option for Soldiers. Further, changes to the program will not impact those who need to reenlist for promotion, reassignment, selection, or other requirements.

“We found that it is pretty common for Soldiers to extend,” Whitney said. “We are adding six additional months to provide a little more predictability for Army units, the Soldier, and their family.”

Many other short-term extension options remain available for Soldiers who need additional time and meet the requisite qualifications, he added.

By Devon L. Suits, Army News Service

About once a decade the call goes out to “diversify” America’s Special Operations Forces. Each time, a study is completed and it turns out that not enough minorities are volunteering for the various training pipelines associated with SOF. Various “fixes” are proposed and invariably fail.

Regardless, SOF is more diverse today than it was just even a few years ago, as more jobs have been opened to female service members. As big as the personnel numbers look (over 70,000 at last count), the enablers in the command are far greater in number and diversity than their operations counterparts. However, few of them spend a career in SOF as they are assigned and promoted by their parent services. Looking out for their careers is hardly the purview of SOCOM. Obviously, this is a double-edged sword for SOF leaders. The operations side of the command isn’t diverse due to lack of interest and the enabler side is diverse but isn’t the primary mission of the organization, leading to support troops often feeling like “second class citizens.”

While efforts should be made to interest a wider audience in service in special operations, abandoning standards for quotas will eventually result in mission failure. As the nation’s political leadership continues to rely upon its special operators to accomplish missions of national importance, failure is not an option.

While the plan doesn’t call directly for quotas, the words used by bureaucrats are there to justify their agenda of mediocrity. The tip of the spear must be free of political interference.

The plan is available for download here.

Soldier Systems Digest subscribers got this yesterday. To ensure you don’t miss out, subscribe here.