WASHINGTON — The Department of Veterans Affairs National Cemetery Administration dedicated new headstones for 17 World War I Black Soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, during a memorial ceremony Thursday, Feb. 22, 2024, at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas.

Retired Lt. Col. Tanya Bradsher, VA deputy secretary and a fourth-generation veteran, said that two years ago to the day, they held a ceremony at the cemetery to unveil a marker to recognize the painful history, hoping to do more.

On Aug. 23, 1917, 156 Soldiers from the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment were involved in what was known as the Houston Race Riots of 1917, also known as the Camp Logan Mutiny, in Houston, Texas. The incident occurred within a climate of overt hostility from members of the all-white Houston Police Department against civilians of the Black community and Soldiers. Of those found guilty, most were given prison sentences, and 19 were sentenced to death and executed. It was found that the courts martial of these Soldiers were hastily conducted and flawed with irregularities. The remains of 17 of the executed Soldiers were reburied at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in 1937 after removal from their original graves at Salado Creek.

The bodies of Cpl. Larnon Brown and Pvt. Joseph Smith, also executed, are buried elsewhere, having been reclaimed by family when they died.

The Army reviewed the cases of these Black Soldiers in 2023 and found their trials unfair, saying that “these Soldiers were wrongly treated because of their race and were not given fair trials.” Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth set aside all convictions and directed the Soldiers’ records reflect honorable discharges.

“Today, the focus isn’t on that history; it is not on the marker, the trials or the Army decision,” Bradsher said. “The focus is on restoring the dignity, honor and respect to those 17 Soldiers and, by extension, to those two Soldiers who were executed and buried elsewhere, and to the 91 Soldiers sent to prison in those same trials.”

Retired Maj. Gen. Matt Quinn leads 155 VA national cemeteries and 122 VA grant-funded state and tribal veteran cemeteries in providing dignified burials in national shrines for veterans and eligible family members.

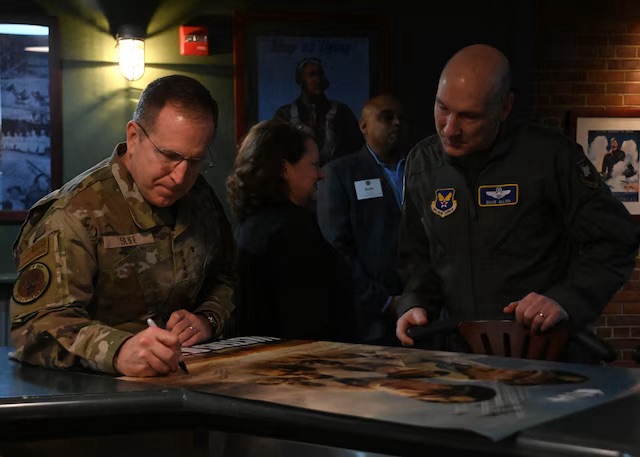

“As an Army veteran and Soldier for life, I’m especially honored to have been present when Army Secretary [Christine] Wormuth set aside the convictions of the 110 Black Soldiers of the 3rd Battalion,” he said. “Today, we right the wrongs of the past and honor the service of these Soldiers who served our country with honor,” he said. “Today, the VA will forever honor their service. This is a proud day for this Soldier, a veteran who would be proud to serve with them.”

These Soldiers were among those executed following the court martials of 110 Black Soldiers charged with murder and mutiny in the 1917 Houston Riots. Consistent with standard procedure of that time for Soldiers who were sentenced to death in a court martial, their graves were marked with headstones that listed only their names and year of death — as opposed to full honors.

Bradsher said equal justice belongs to all Soldiers.

“This day reflects the progress we have made as a nation since these men were first interred here a century ago,” she said. “Progress makes clear that all institutions must live up to the ideals and promise of our nation’s constitution.”

She said the headstones are more than physical markers. They are a symbol of promise and progress. They uphold the promise enshrined in the Constitution.

“All Americans have equal rights and equal worth. They represent the struggle and fight to keep the stories of these men alive,” she said. “These headstones now look like every other honorable veteran buried here. It represents the approval of a final resting place for these 17 Soldiers. They will be recognized and forever called veterans.”

She said their headstones will show their ranks, signifying their dedication, leadership and commitment to duty. They will also show their states of origin, reminding people that people who volunteer to serve come from states across the U.S, and their regiment, connecting them to servicemen and women with shared experiences across generations who safeguard the nation.

“These headstones will not erase history or right the wrongs of the past, but they will ensure future generations can understand that history and remember their names,” she said.

Yvette Bourcicot, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, said this event was meaningful to her as an Air Force veteran.

“These Soldiers are going to take their rightful place in history alongside African-Americans who have served this country honorably and deserve our respect,” she said. “We do ask for forgiveness for the injustice that was perpetrated on these Soldiers, and we’re doing everything we can to make this right. The Army is a learning institution, and we’re learning as we go. I’m appreciative to be here, representing what we’ve done.”

Bourcicot presented the descendants military service certifications with the upgraded honorable discharges and restored ranks. The corrected records are accessible to the public.

“While this can’t take away the generations of pain and trauma their loved ones endured, we hope these actions will serve as one more step down the path of restorative justice,” she said. “Their memory lives in every one of us and will inspire future servicemen and women to continue cultivating the Army and our sister services into a place where everyone who wants to serve can. We can’t erase the past, but we can learn from it and use it to guide our future.”

Jason Holt, a relative of Pfc. Thomas Hawkins, who was executed, acknowledged the painful history of the Houston Riot and praised federal officials like Bourcicot for taking steps to support the Soldiers decades after the event.

“It’s not easy for these folks here today to go back to their respective places of power and say they did something that involved racism,” Holt said. “To say that they did something to set aside convictions, to say they did something that was controversial. It’s not an easy job. I salute your courage.”

Holt was among three family members of Soldiers who received certificates in recognition of their relatives’ service.

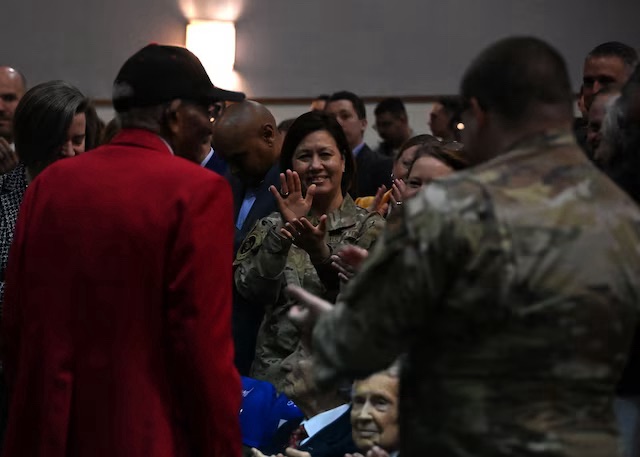

The ceremony included a three-round volley, the playing of taps and presentation of colors, along with the unveiling of the headstones.

The Soldiers who received the honors were: Cpl. Charles Baltimore, Pfc. William Breckenridge, Pvt. Albert Wright, Pvt. James Divins, Pvt. James Robinson, Pvt. Thomas McDonald, Pvt. Babe Collier, Cpl. James Wheatley, Pvt. Frank Johnson, Sgt. William Nesbit, Pvt. Pat McWhorter, Pfc. Thomas Hawkins, Pvt. Risley Young, Pvt. Ira Davis, Pfc. Carlos Snodgrass, Pfc. William Boone and Cpl. Jesse Moore.

More than 180,000 service members, spouses and family members are buried in the cemetery at Fort Sam Houston.

By Shannon Collins