1st SOCOM distinctive unit insignia (Photo Credit: U.S Army)

On August 7, 1984, Maj. Gen. Joseph C. Lutz stood beside his wife Joyce in the shadow of the Special Forces Soldier statue, known to most as “Bronze Bruce,” and fought back tears while the 24th Infantry Division band played “Auld Lang Syne.” Fifteen minutes earlier, Lutz had passed the colors of the U.S. Army 1st Special Operations Command (1st SOCOM), which he had commanded since its founding two years earlier, to Maj. Gen. Leroy N. Suddath, Jr.

1st SOCOM shoulder sleeve insignia (Photo Credit: U.S Army)

Opposite the incoming and outgoing commanders stood a formation representing the Army Special Forces (SF), Rangers, Psychological Operations (PSYOP), and Civil Affairs (CA) units that came under the command of 1st SOCOM upon its provisional establishment on October 1, 1982, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina (known as Fort Liberty since 2023). Prior to that, no single command and control headquarters existed for all Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) units. Since then, the Army has not lacked one, with the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) filling that role since December 1989.

“A Rocky Road”

General Robert W. Sennewald presided over the change of command ceremony, as the commander of 1st SOCOM’s higher headquarters, the U.S. Army Forces Command. In his remarks, he noted the rocky road that 1st SOCOM had travelled to get to where it was in August 1984. Without elaborating on the specific obstacles overcome by 1st SOCOM, Sennewald’s comments likely resonated with the Vietnam-era ARSOF leaders in attendance, including Lutz. After great sacrifice and exceptional valor in Vietnam, many ARSOF units endured force reductions and resourcing shortages in the aftermath of that war. By the late 1970s, ARSOF was reeling from years of neglect.

After leaving 1st SOCOM in August 1984, Maj. Gen. Joseph C. Lutz served as Chief of the Joint United States Military Aid Group to Greece. Here his pictured (second from right) briefing U.S. Secretary of State George Schultz (far right) at Hellenikon Air Base, Greece. (Photo Credit: NARA)

From his position as the Commander, U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Center for Military Assistance, Lutz had played a significant role in revitalizing ARSOF, and Army Special Forces, in particular. Under his leadership, the Center produced an Army-directed Special Operations Forces Mission Area Analysis that prescribed some of the most impactful changes to ARSOF in the 1980s, including the establishment of 1st SOCOM. Sennewald testified to Lutz’s impact, saying, “Our national leadership made a commitment to develop your capabilities, and General Lutz has been instrumental in bringing this commitment to reality.”

With a mission to prepare, provide, and sustain active-duty Army SF, PSYOP, CA, and Ranger units, 1st SOCOM was the first headquarters to exercise both administrative and operational control of the full spectrum of ARSOF. On Lutz’s watch, the command had fought a brief war on the Caribbean Island of Grenada (Operation URGENT FURY) and deployed mobile training teams to sixty-five countries, including such hotspots as El Salvador, Honduras, and Lebanon.

Maj. Gen. Leroy N. Suddath, Jr. (left) and Col. John N. Dailey (right) are pictured here at the October 1986 activation ceremony for the 160th Special Operations Aviation Group at Fort Campbell Kentucky (Image Credit: U.S. Army). (Photo Credit: U.S Army)

Under the leadership of Lutz and his successor, Maj. Gen. Suddath, 1st SOCOM continued to revitalize and expand ARSOF, reversing some of the post-Vietnam cuts and adding new capabilities. In 1984 alone, the command oversaw the reactivation of 1st Special Forces Group (SFG) and the addition of a Ranger Regimental headquarters and the 3rd Ranger Battalion. Early the following year, the Army transferred Task Force-160, a dedicated ARSOF Aviation unit, from the 101st Airborne Division to 1st SOCOM. This unit was reorganized into the 160th Special Operations Aviation Group (SOAG) in October 1986. 1st SOCOM also added two dedicated ARSOF Support units that year.

By 1987, when 1st SOCOM became the Army component of the newly established U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), its major subordinate units were the 75th Ranger Regiment; the 1st, 5th, 7th, and 10th Special Forces Groups; the 4th PSYOP Group; the 96th CA Battalion; the 528th Support Battalion; the 112th Signal Battalion; and the 160th Special Operations Aviation Group.

Toward a MACOM

In 1988, Suddath passed command to Maj. Gen. James A. Guest, an SF veteran of the Vietnam War who had previously commanded the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School and 5th SFG. Under Guest’s leadership, 1st SOCOM successfully advocated for the establishment of a Major Command (MACOM) for ARSOF. On December 1, 1989, the Army activated USASOC, under the command of Lt. Gen. Gary E. Luck, as the Army’s sixteenth MACOM.

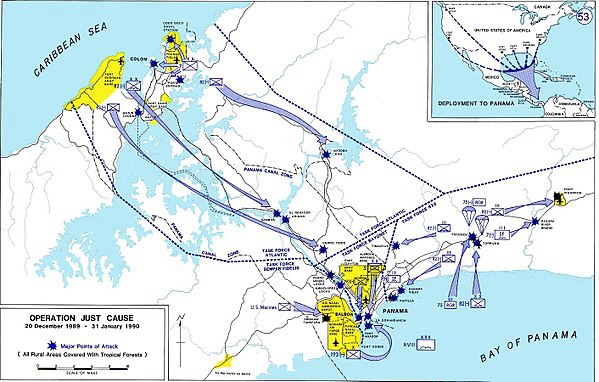

Concurrently, 1st SOCOM became a major subordinate command of USASOC, responsible for all active-duty ARSOF, alongside the short-lived U.S. Army Reserve Special Operations Command taking command of all U.S. Army Reserve (USAR) and Army National Guard (ARNG) SOF units. Guest continued serving as 1st SOCOM commander through this transition period, during which the command rapidly deployed large contingents in support of Operation JUST CAUSE in Panama and Operation DESERT SHIELD in Saudi Arabia.

On November 27, 1990, 1st SOCOM was redesignated as the U.S. Army Special Forces Command (USASFC) and assigned the mission of equipping, training, and validating all Army Special Forces, including two ARNG and two USAR SF Groups. This arrangement persisted until 2014, when USASFC merged with active-duty PSYOP, CA, and ARSOF Support units to form the 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne), a division-level ARSOF headquarters under USASOC that commands and controls five active-duty and two ARNG SF groups, two PSYOP groups, a CA brigade, and a Sustainment brigade.

“You have arrived.”

It is difficult to see how organizations such as USASOC and 1st Special Forces Command would exist, had it not been for forward-thinking leaders like Joseph Lutz, Leroy Suddath, and James Guest. These three were the only commanders of 1st SOCOM, the first modern ARSOF headquarters.

Despite the long and sometimes rocky road back from the post-Vietnam doldrums, General Sennewald saw only positives in August 1984. “Today,” he said, “I am firmly convinced that road is part of history. If the words ‘you have arrived’ have meaning to anyone, they should have special meaning to the soldiers of 1st SOCOM.”

In the intervening four decades, ARSOF has continued to prove its value to the nation in myriad ways and innumerable places, in conflicts big and small, always striving to live up to the motto first adopted by 1st SOCOM in 1982: Sine Pari, meaning “Without Equal.” In his parting comments, Lutz expressed a sentiment shared by ARSOF leaders ever since when he said, “I want to thank General Sennewald and our Army for allowing me the privilege to command the greatest soldiers in the world.”

By Christopher E. Howard