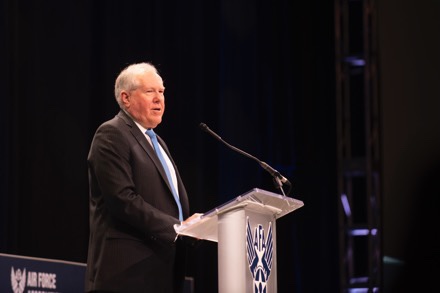

ORLANDO, Fla. (AFNS) —

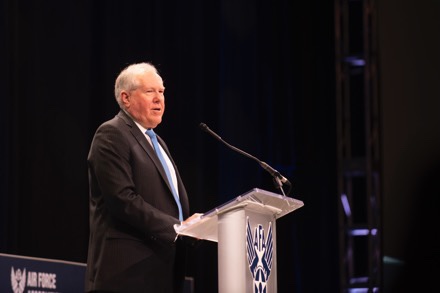

Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall outlined his increasingly urgent roadmap March 3 for successfully bringing about the new technologies, thinking, and cultures the Air and Space Forces must have to deter and, if necessary, defeat modern day adversaries.

The particulars of Kendall’s 30-minute keynote to Air Force Association’s Warfare Symposium weren’t necessarily new since they echoed main themes he’s voiced since becoming the Department’s highest ranking civilian leader. But the circumstances surrounding his appearance before an influential crowd of Airmen, Guardians, and industry officials were dramatically different, coming days after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Kendall used the invasion to buttress his larger assertion that the Air and Space Forces must modernize to meet new and emerging threats and challenges. The path to achieving those goals are embodied in what Kendall has dubbed the Department of the Air Force’s “seven operational imperatives.”

“My highest personal goal as Secretary has been to instill a sense of urgency about our efforts to modernize and to ensure that we improve our operational posture relative to our pacing challenge; China, China, China,” he said. “The most important thing we owe our Airmen and Guardians are the resources they need, and the systems and equipment they need, to perform their missions.”

“To achieve this goal, I’ve commissioned work on seven operational imperatives. These imperatives are just that; if we don’t get them right, we will have unacceptable operational risk,” he said.

Kendall spent the balance of his address discussing each of the seven imperatives. But he also noted that, given recent events, the threats are not abstract.

“In my view President Putin made a very, very, serious miscalculation. He severely underestimated the global reaction the invasion of Ukraine would provoke, he severely underestimated the will and courage of the Ukrainian people, and he overestimated the capability of his own military,” Kendall said.

“Perhaps most of all, he severely underestimated the reaction from both the U.S. and from our friends and allies,” he said.

The world’s mostly united response to Ukraine should not divert attention from the distance the Air and Space Forces must cover to adequately upgrade and change to face current threats.

“We’re stretched thin as we meet Combatant Commanders’ needs around the globe,” Kendall said, repeating a frequent refrain. “We have an aging and costly-to-maintain capital structure with average aircraft ages of approximately 30 years and operational availability rates that are lower than we desire.”

Kendall added, “While I applaud the assistance the Congress has provided this year, we are still limited in our ability to shift resources away from legacy platforms we need to retire to free up funds for modernization. … We have a Space Force that inherited a set of systems designed for an era when we could operate in space with impunity.”

Those realities, he said, triggered establishing the Department’s seven operational imperatives. They are:

1. Defining Resilient and Effective Space Order of Battle and Architectures;

2. Achieving Operationally Optimized Advanced Battle Management Systems (ABMS) / Air Force Joint All-Domain Command & Control (AF JADC2);

3. Defining the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) System-of-Systems;

4. Achieving Moving Target Engagement at Scale in a Challenging Operational Environment;

5. Defining optimized resilient basing, sustainment, and communications in a contested environment;

6. Defining the B-21 Long Range Strike Family-of-Systems;

7. Readiness of the Department of the Air Force to transition to a wartime posture against a peer competitor.

The first imperative, he said, is aimed at ensuring capabilities in space. “Of all the imperatives, this is perhaps the broadest and the one with the most potential impact,” he said.

“The simple fact is that the U.S. cannot project power successfully unless our space-based services are resilient enough to endure while under attack,” he said. “Equally true, our terrestrial forces, Joint and Combined, cannot survive and perform their missions if our adversary’s space-based operational support systems, especially targeting systems, are allowed to operate with impunity.”

The second of Kendall’s seven imperatives is to modernize command and control, speed decision-making and linking seamlessly multi-domain forces. In short he wants continued development of defense-wide effort known as Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) and the Air Force component of that effort known as ABMS or Advanced Battle Management System.

“This imperative is the Department of the Air Force component of Joint All Domain Command and Control. It is intended to better define and focus DAF efforts to improve how we collect, analyze, and share information and make operational decisions more effectively than our potential adversaries,” Kendall said.

At the same time, that effort demands discipline. In this regard, Kendall was blunt, saying “we can’t invest in everything and we shouldn’t invest in improvements that don’t have clear operational benefit. We must be more focused on specific improvements with measurable value and operational impact.”

Another imperative is Defining the Next Generation Air Dominance (or NGAD) System of Systems.

“NGAD must be more than just the next crewed fighter jet. It’s a program that will include a crewed platform teamed with much less expensive autonomous un-crewed combat aircraft, employing a distributed, tailorable mix of sensors, weapons, and other mission equipment operating as a team or formation,” he said.

Kendall’s next imperative is “Achieving Moving Target Engagement at Scale in a Challenging Operational Environment.”

The effort, he said, has direct connection to the JADC2/ABMS initiatives but tightens the focus.

“What enables our aforementioned ABMS investments to be successful starts with the ability to acquire targets using sensors and systems in a way that allows targeting data to be passed to an operator for engagement,” he said, adding, “for the scenarios of interest it all starts with these sensors. They must be both effective against the targets of interest and survivable.”

The next imperative is a pragmatic throwback to a concept that has long been important – defining optimized resilient basing, sustainment, and communications in a contested environment.

But as in other efforts, Kendall says the concept needs new thinking. In addition to relying on large, fixed bases as the Air Force has done for generations, Kendall said there needs to be a new “hub-and-spoke” arrangement that includes smaller, more mobile bases. That concept is known as Agile Combat Employment (ACE).

“It’s the idea that you don’t just operate from that one fixed base. You have satellite bases dispersed in a hub-and-spoke concept, where you can operate from numerous locations and make your forces less easily targetable because of their disbursement,” he said.

The sixth imperative has a heavy focus on hardware. The effort will define the B-21 Long Range Strike “family of systems,” he said.

As in other imperatives, this one has echoes to others in the list. “This initiative, similar to NGAD, identifies all of the components of the B-21 family of systems, including the potential use of more affordable un-crewed autonomous combat aircraft,” he said.

“The technologies are there now to introduce un-crewed platforms in this system-of-systems context, but the most cost effective approach and the operational concepts for this complement to crewed global strike capabilities have to be analyzed and defined.”

As a former senior weapons buyer for the Department of Defense, Kendall has a keen understanding of the tension between equipment and cost. That understanding explains, in part, this imperative.

“We’re looking for systems that cost nominally on the order of at least half as much as the manned systems that we’re talking about for both NGAD and for B-21” while adding capability, he said. “ … They could deliver a range of sensors, other mission payloads, and weapons, or other mission equipment and they can also be attritable or even sacrificed if doing so conferred a major operational advantage – something we would never do with a crewed platform.”

The seventh and final imperative is both ageless and essential – readiness.

“To go from a standstill to mobilizing forces, moving them into theater, and then supporting them takes the collective success of a large number of information systems and supporting logistical and industrial infrastructure. We have never had to mobilize forces against the cyber, or even the kinetic, threats we might face in a conflict with a modern peer competitor,” he said.

While achieving the imperatives is challenging, Kendall said he’s optimistic.

Kendall said industry, with its “intellectual capital” will have a critical role in finding solutions and compressing the often decades-long development time. So will allies and, of course, Airmen and Guardians.

“I’ve gotten to meet a lot of Airmen and Guardians. Nothing is more inspiring to me than to have informal conversations with the men and women who wear the Air or Space Force uniform. The dedication, commitment, professionalism, and passion these people bring to their service and to the nation is simply awesome,” he said.

“As I’ve traveled to places like Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, and Thule, Greenland, the positive attitudes, drive, and commitment our men and women serving far from home, and in sometimes challenging circumstances, is just exceptional.”

By Charles Pope, Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs