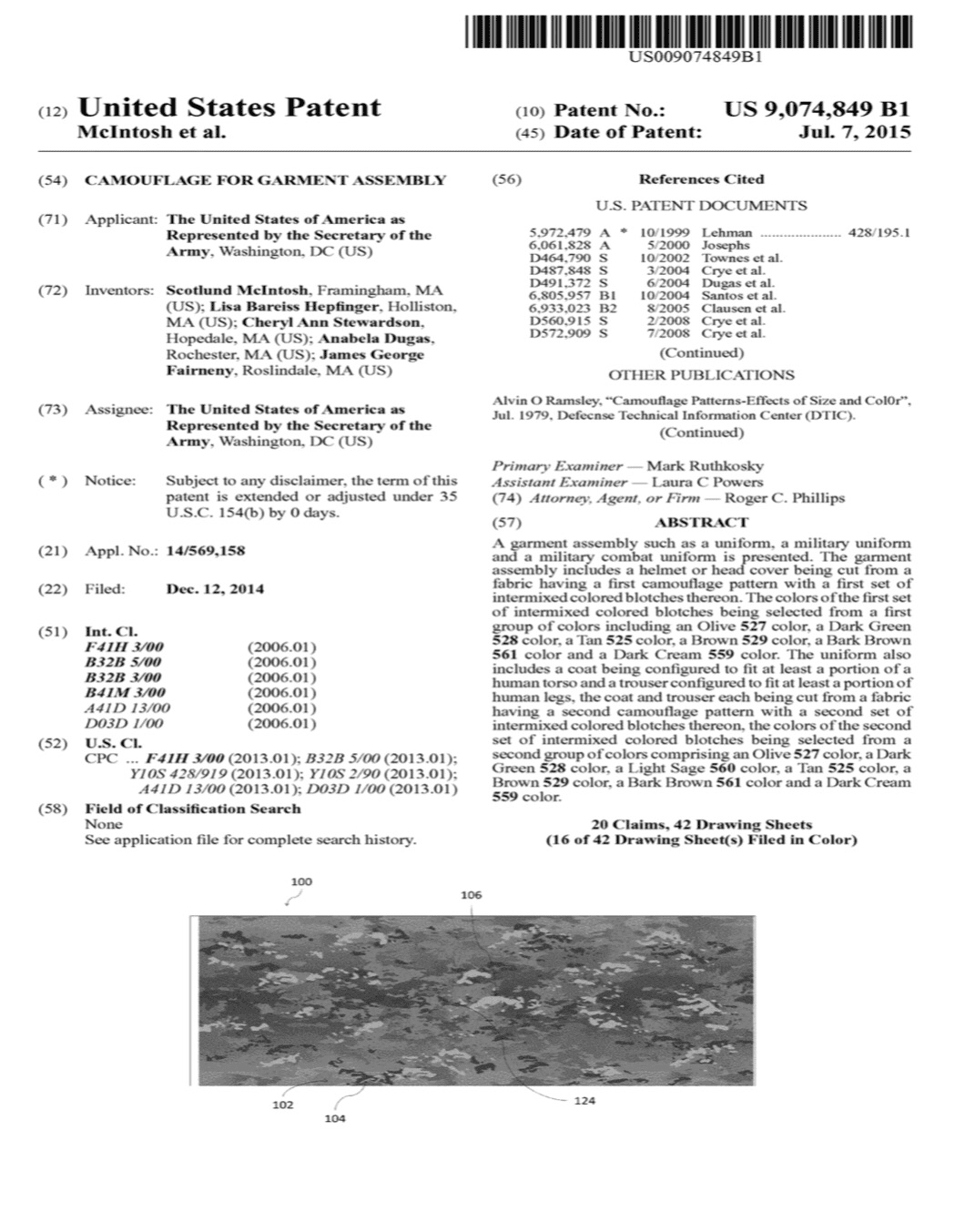

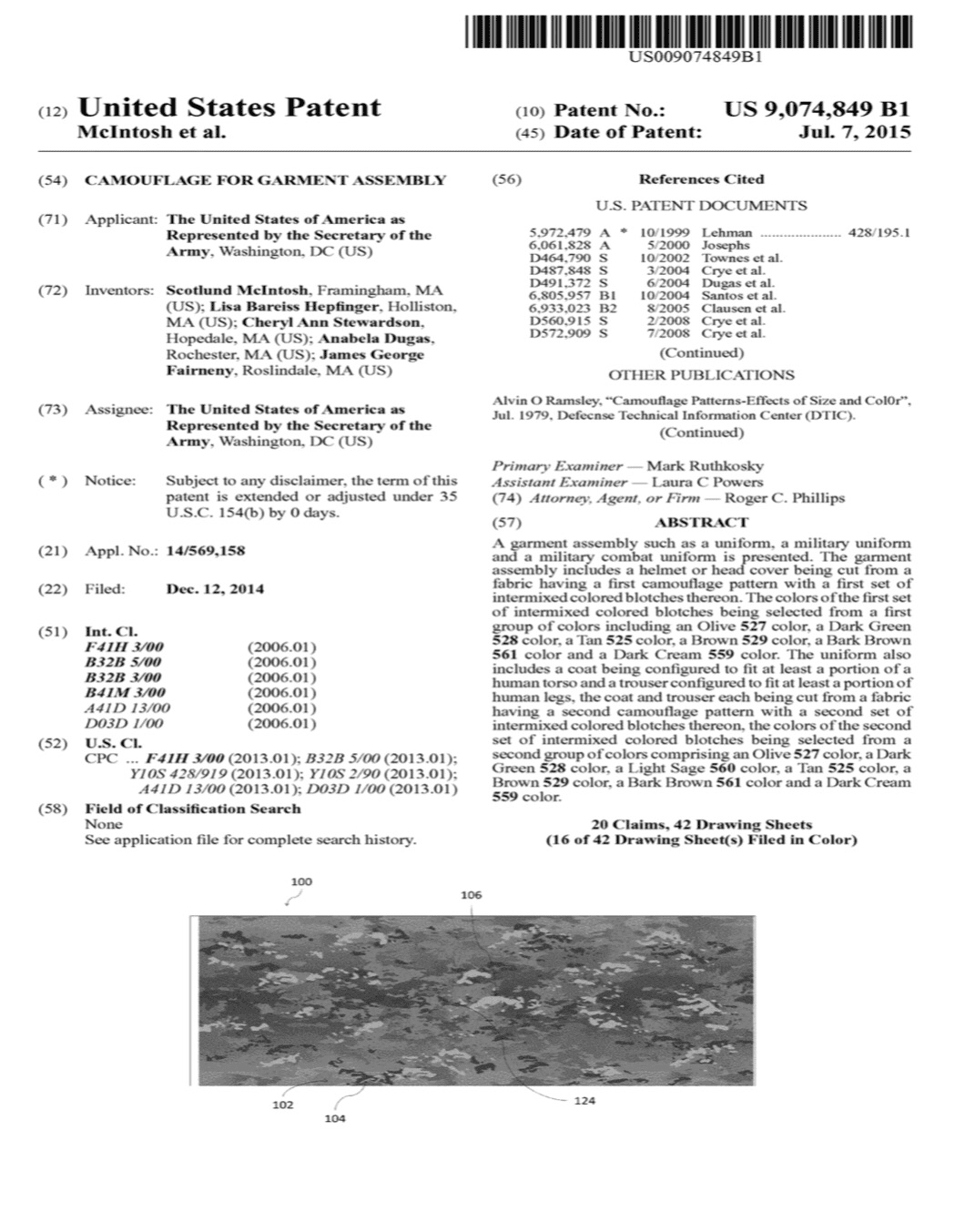

On 7 July, 2015 the US Patent and Trade Office issued Utility Patent 9,074,849, Entitled: “Camouflage for Garment Assembly” to the United States of America as represented by the Secretary of the Army. It followed Utility Patent 9,062,938, Entitled: “Camouflage Patterns”, issued two weeks earlier on 23 June, 2015. Both cover Scorpion W20601, initially developed in 2010 by engineers at the Natick Soldier Systems Center and later, after further refinement, recently adopted as the Army’s new Operational Camouflage Pattern.

There are a few curious things about this patent. First off, it’s practically an opus at 59 pages, although admittedly, there are a lot of illustrations. Also, it was issued very quickly, and coincidentally, just in time for the beginning of the Army’s OCP transition. Next, it doesn’t feel like it was written by a patent attorney, but rather by an engineer who was sure to include a great deal of fascinating, although extraneous information on how the pattern was developed and tested. Oddly enough, the Army hasn’t said a peep about it, which is strange considering they continue to assert “appropriate rights to the pattern“. However, once you dig into the details of the patent, you may see why they’ve stayed mum. Finally, the type of data disclosed in the patent tells an interesting story. But before we get to that, let’s address the patent itself.

The Abstract

A garment assembly such as a uniform, a military uniform and a military combat uniform is presented. The garment assembly includes a helmet or head cover being cut from a fabric having a first camouflage pattern with a first set of intermixed colored blotches thereon. The colors of the first set of intermixed colored blotches being selected from a first group of colors including an Olive 527 color, a Dark Green 528 color, a Tan 525 color, a Brown 529 color, a Bark Brown 561 color and a Dark Cream 559 color. The uniform also includes a coat being configured to fit at least a portion of a human torso and a trouser configured to fit at least a portion of human legs, the coat and trouser each being cut from a fabric having a second camouflage pattern with a second set of intermixed colored blotches thereon, the colors of the second set of intermixed colored blotches being selected from a second group of colors comprising an Olive 527 color, a Dark Green 528 color, a Light Sage 560 color, a Tan 525 color, a Brown 529 color, a Bark Brown 561 color and a Dark Cream 559 color.

One could take this revelation at face value, concluding that “the Army did it, they beat Crye!” But not so fast. That Utility Patent might not be all it’s cracked up to be.

Types Of Patents

I’d like to point out that this is a Utility Patent which is very specific and the Army doesn’t seem to have done itself any favors in the specificity of its claims. For those unfamiliar, the claims of a patent are the points that are being protected and the patent itself is essentially a right to exclude, meaning the patent holder gets to decide who can use the intellectual property it protects.

Since it’s a patent, you’ll probably want to immediately put it on the same footing as Crye Precision’s existing MultiCam patent, thinking one cancels out the other. Not so. Lineweight LLC, which is the holding company for all of Crye Precision’s patents, holds a Design Patent for the MultiCam pattern (D592,861). But, a Design Patent is more broad in nature. Think of it as a picture rather than a description of specific elements of the picture.

A Patent’s A Patent, Right?

So what’s the difference between these two types of patents you might ask?

To get around a Utility Patent all you have to do is make changes to what you’ve got until you no longer violate the specific claims of the patent. The more specific the claims are, the easier this is to do.

On the other hand, to determine if someone has violated a Design Patent, they use the “ordinary observer” test. Essentially, if it looks like it infringes to the average person, it does.

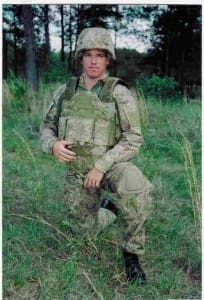

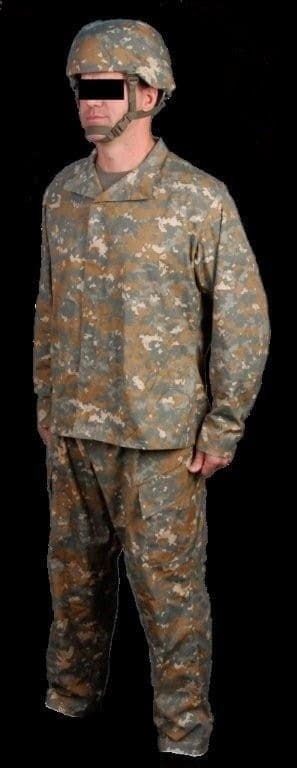

At casual inspection, Scorpion W2 sure looks close to me. Just examine this photo. Which swatch of fabric is Scorpion and which is MultiCam?

What’s It All Mean?

While I’m sure Crye Precision is aware of this patent, it’s so new and so restrictive that I doubt they’ll do anything about it. There’s no reason to. Ultimately, the Scorpion patent doesn’t affect Crye’s existing MultiCam IP or any of its contractual agreements with printers. Despite the Army’s new Utility Patent, they will continue to pay a license fee to Crye through the printers in order to use the Scorpion pattern.

Update – Info Regarding Related Patent 9,062,938

The Army fasttracked not just one, but two patents; the “garment assembly” patent which is the main subject of this article, as well as another patent granted about two weeks earlier concerning just the pattern. Both are Utility Patents and contain much the same information regarding the percentages of color used to make up the Scorpion W2 camouflage pattern. While the “Camouflage Patterns” patent also contains all of the extensive information about the ACU and helmet cover substrate, it is just two pages shorter at 57, but does acknowledge up front that it is related to the “garment assembly” patent and incorprates the same data directly from the other patent.

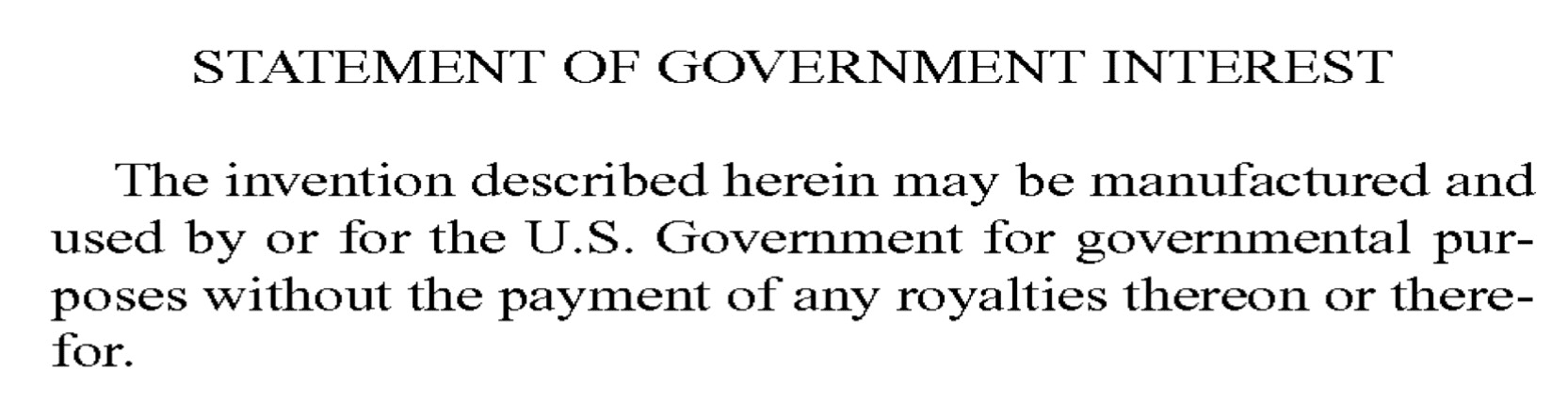

Both patent also include this section:

This is the ‘Hail Mary’ play that the Army has included in the patents. Unfortunately for them, it won’t have the effect the Army has hoped for. They are showing these patents to printers and telling them that they no longer have to pay a royalty. All it seems to be accomplishing is causing further tension in the supply chain as the Army expects businesses to violate contractual obligations and then doesn’t understand why they can’t.

Crye Precision collects the licensing fees for MultiCam and Scorpion from printers through royalty agreements. The Army pays those fees as part of the per unit cost of each garment, just like they do for permethrin treatment. The printers entered into industry standard licensing agreements which were written to protect the MultiCam pattern. It’s business. These patents don’t nullify contracts between Crye Precision and the printers.

It’s All About The Colors

Although the document does go into detail as to why other, prior art camouflage patterns don’t quite work, the actual claims in the Army’s patent revolve mainly around percentages of colors, even down to the tenth of a percentile. That’s right, the Army patented colors. I seem to recall a certain Colonel at PEO Soldier telling the media that Crye couldn’t extend Intellectual Property protection to the colors in the MultiCam pattern and yet, that’s exactly what the Army just did. Feel free to eat some crow on me, Bob.

This heavy reliance on colors to attain the patent is the pattern’s very weakness and may be why the Army hasn’t trumpeted the issue of this Utility Patent, because it literally invites counterfeiters. It is so specific, even the slightest change gets around the limited protection of this patent. In fact, because it contains so much information, the patent itself serves as a recipe on how to get around its very protection. This leaves the Army at the mercy of Crye Precision who has the more expansive Design Patent. It would be up to Crye to determine whether any newly minted Scorpion knockoffs violate the MultiCam patent and then police them.

What About The Bookends?

What does this mean for the so-called bookend patterns? The Army’s new Utility Patent obviously doesn’t protect any color variants due to its specificity, so they wouldn’t be protected by this patent.

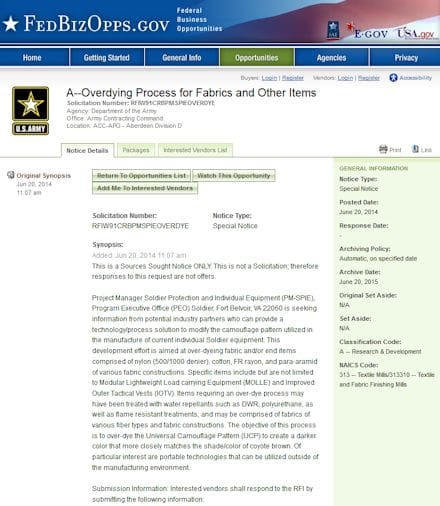

And Now, The Rest Of The Story

There’s another, bigger story, lurking in the language of the patent. For over a year now, we’ve been awaiting details on the Army’s rather abbreviated testing used to select the Scorpion pattern. The Army was able to determine in a matter of weeks that Scorpion was the one for them when previous, Camouflage Improvement Effort Phase IV testing had taken well over a year to complete. For some odd reason, they included a great deal of extraneous testing information in the patent, perhaps in their haste to rush the patent through, for the official transition from UCP to OCP on 1 July, 2015.

The application was just submitted on 12 December, 2014. While unusual to be granted so quickly, as I understand it, this is perfectly legal. Although, the application was never published and there was no period for public comment regarding the patent prior to it being granted.

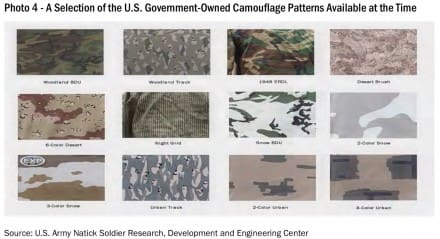

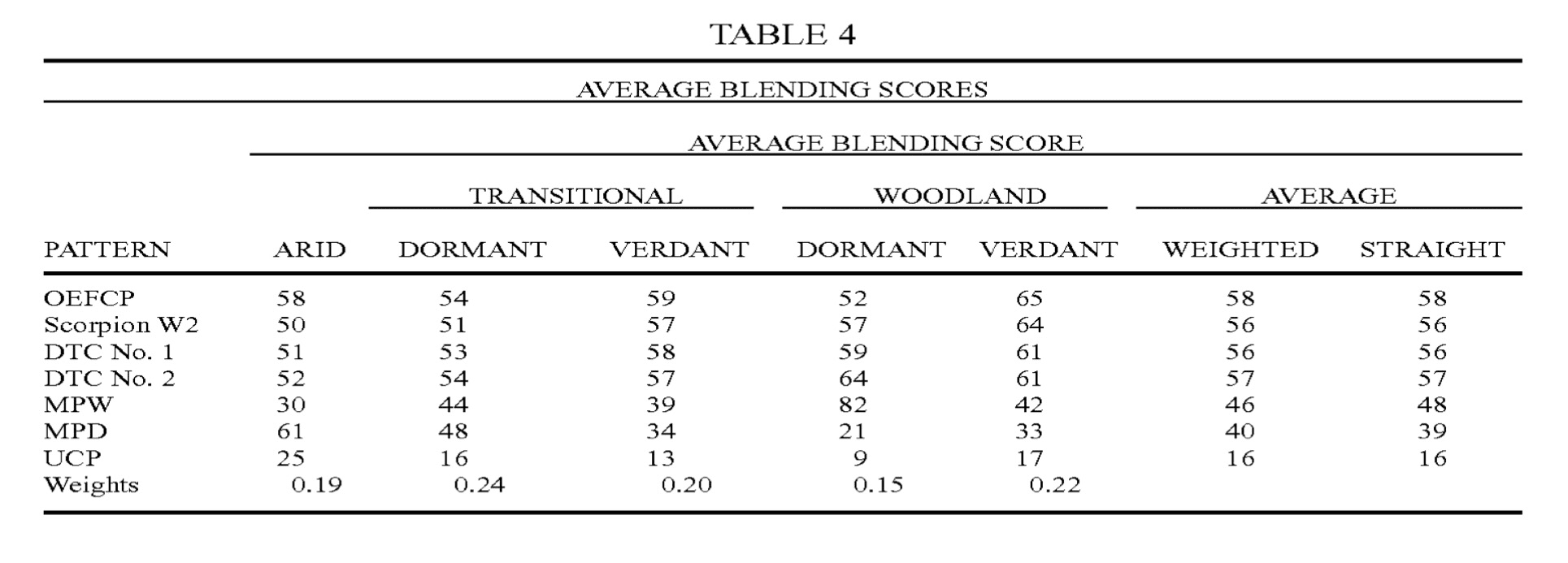

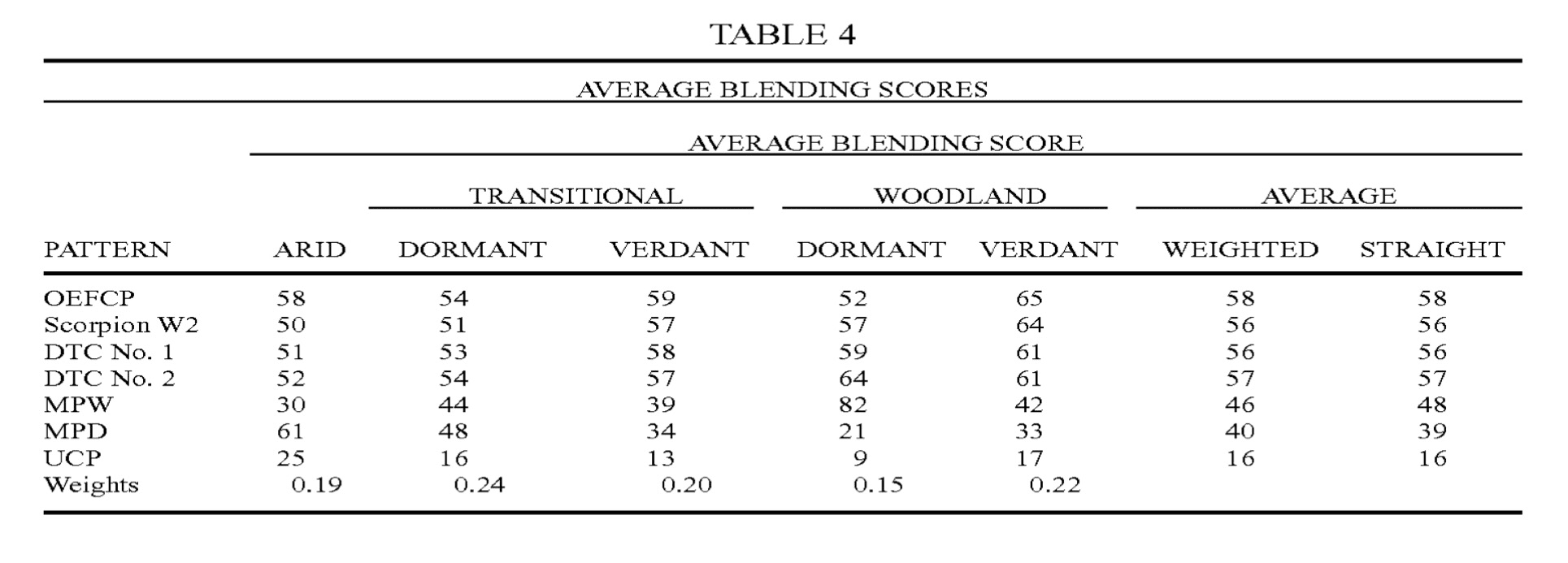

But back to testing. According to the patent, the Army conducted picture-in-picture testing of MultiCam, Scorpion, Digital Transitional Patterns 1 & 2, MARPAT Woodland & Desert and the incumbent Universal Camouflage Pattern across several simulated environments. These were Transitional (Arid, Dormant and Verdant) and Woodland (Dormant and Verdant). This chart (Table 4), embedded in the patent, shows how the patterns performed.

UCP Performs Horribly

Before we go any further, take a gander at UCP’s performance; just abysmal. It makes you wonder how long the Army has known about its performance and how long they ignored it. As it is, this set of testing was conducted in Spring 2014 and we know for sure UCP was also tested during Phase IV, back in 2012 but the Army won’t release those test results.

With Camouflage, Specialization Is A Blessing As Well As A Curse

This chart also validates something else we know to be true. Environmental specific patterns do very well in the environment they are tuned to, but work against the wearer in other environments. Just take a look at the performance of the two MARPAT variants across the environments to see how that works.

Scorpion Doesn’t Perform As Advertised in Arid Environments

The Army also makes an untrue claim in the patent application, declaring the Scorpion pattern, designated 100 in the patent, “significantly better” than all other candidate patterns in the Transitional Arid environment during picture-in-picture testing. As you can see from the patent’s chart, this simply isn’t true. In reality, it performed fifth out of seven patterns. Considering that America’s Army continues to be engaged with our enemies in Arid regions, this is ridiculous to purposefully adopt a pattern that performs worse than what they’ve already got. They made a similar claim regarding the Woodland Dormant environment but naturally, Scorpion was outperformed by the encironmentally specific MARPAT Woodland.

Turns Out, MultiCam Is Best

Despite explaining in the patent why MultiCam doesn’t work, testing demonstrated otherwise. What we learn, from the Army’s own published research, is that OCP aka Scorpion W2 doesn’t perform as well as OEFCP aka MultiCam, except in one environment, the Woodland Dormant environment (think fall and winter). Let me put it another way. According to Army testing, MultiCam outperforms Scorpion in four out of five critical operating environments. And yet, the Army adopted Scorpion anyway and is paying Crye Precision a royalty for this lesser performing pattern. Scorpion or MultiCam, Crye Precision receives a royalty. The Army spent time and taxpayer money to develop a pattern that performs less well than what they already had. In summation, the uniforms our Soldiers are getting now (OCP) don’t perform as well as the uniforms they were issued even a month ago (OEFCP).

Bottom Line

Based on the data presented in the patent, you can only come to one conclusion. When you consider cost and performance, the Army should just drop the charade and fully adopt Crye’s MultiCam. Even better, the Army would gain access to Crye’s environmental specialty patterns which are already seeing limited operational use with certain customers.

A Note To Readers:

I’d like to wrap this up by pointing out that I am not a lawyer, but I did read the patent, and that for brevity, I’ve described some things, like types of patents, in rather generic terms. I’ll let the actual patent attorneys argue over the intricacies of Intellectual Property law but I’m sure there will be plenty of others who also want to chime in. All I ask is that you have an idea of what you are talking about and are prepared to explain the basis of any comments.

This article was updated on 16 July, 2015 to add imformation about patent 9,062,938 “Camouflage Patterns”, 23 June, 2015.