I am going to take this opportunity to introduce readers to small, specialized, teams of infantry called “Pathfinders.” Teams that no longer exist. Pathfinders were first trained and employed during the last half of WWII. Through trial and error, in combat and training, Commanders realized that mass Airborne Operations were more successful if someone was already on the ground to confirm and clearly mark drop zones. The mission required newly formed Pathfinder teams to jump in early to provide that critical ground to air link for larger follow-on formations of Airborne troops. The Pathfinders proved their utility in combat and the skills were retained exclusively by Airborne units after the war.

In 1947, the history starts to get a little more complicated. The Air Force became a separate service that year. There was some consideration at the time for aligning Army Airborne Divisions in some fashion under the Air Force. Perhaps akin to the USMC and US Navy relationship. Of course, we know that did not happen. However, the Air Force did want to retain control of their aircraft delivering Army forces. Therefore, they formed the Combat Control Teams (CCTs) with essentially the same mission – and linage – as the original Army Pathfinders. Indeed, this issue was an early exemplification of the reality that the operational mission “divorce settlement” of the two Services was never entirely clean cut. For instance, then and even today, the Army continued to fly quite a few of its own fixed wing STOL cargo and support aircraft. The C7 Caribou and the C23 Sherpa being just two examples.

Still, with the CCTs available in sufficient numbers, many in both Services began to consider the Army’s remaining few Pathfinder teams redundant at best for Air Force supported Airborne Operations. That might very well have spelled the end for the Pathfinders. However, that all changed dramatically with the introduction of capable “medium lift” helicopters after the Korean War. Specifically, the UH1 “Huey” that started coming into limited service in 1956; and shortly thereafter was being delivered in both “Slick” and heavily armed versions. Suddenly, the Army could imagine and practice a version of “Air Mobile” operational maneuver warfare that was much less dependent on Air Force lift assets. Likewise, a new more robust pattern for Army Pathfinder distribution and employment emerged.

As the Army fielded rotary wing aviation units throughout the force, Pathfinder trained infantry teams of various sizes were assigned to each new formation. That is the arrangement that was tested in combat in Vietnam from the time the first conventional Army units were deployed until the last major unit redeployed. Since I cannot do that extensive history justice in the space of this article, I am going to recommend two references for those that might want to have more details. One is a link to the Pathfinder Association’s website. The link goes to a page which has an official Army video of Pathfinder School, circa 1969. Army Pathfinder History Vietnam (nationalpathfinderassociation.org)

Additionally, there is a book available in paperback by Richard R. Burns, called “Pathfinder: First In, Last Out” that describes his training at Fort Benning and subsequent experience in Vietnam as a Pathfinder in the 101st Airborne 1967-68. The book was published in 2002 and is the only one I know of that is exclusively focused on Pathfinders. Unfortunately, Burns died of cancer in 2001 before the book went to print. I read it years ago and then read it again before writing this. It would have been invaluable to me if it had been available in 1976 when I joined the Pathfinder Detachment of the 3rd Aviation Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division, Kitzingen, Germany.

Obviously, peacetime service in Germany is in no way equivalent to combat duty in Vietnam. However, the techniques, tools, and Pathfinder mission profiles, Burns describes are very familiar to me. Not surprising really, since the Pathfinder Handbook I studied was dated 1970 and the gear we wore, carried, and employed, was almost all Vietnam vintage – if not earlier. Pathfinders are trained to set up and operate Fixed-Wing Landing Strips (FLSs) for aircraft that need a runway, Drop Zones (DZs) for cargo and personnel delivered by parachute, and Helicopter Landing Zones (HLZs) for vertical takeoff and landing birds. However, facilitating helicopter borne insertions and larger scale air assaults is the signature tactical mission that Pathfinders have been best known for since the 1960s. Any MOS can become a Pathfinder, and running a singular PZ, DZ, or HLZ is MOS agnostic. But the inherent tactical tasks involved in that close combat mission helps explain why Pathfinder units were specifically manned by infantry soldiers.

We did our fair share of air assault missions in Germany. Certainly, compared to Vietnam, our air assaults were relatively small and of short duration. Usually involving a single Rifle Company, but a couple of times it was an entire Infantry Battalion. The Aviation Battalion had only one “Lift Company” – that the Pathfinders were also assigned to. IIRC we only had a total of 20 UH1s and a smaller number of OH58s. The Huey, fully loaded, was designed to carry 11 passengers (PAX) + Crew, and a Rifle Squad in those days was 11 soldiers. 10-12 birds were about all that could realistically be made available at any one time. Therefore, a lift could be no more that 110-132 Pax total. In other words, approximately one Rifle Company – minus heavier weapons like dismounted TOWs and Mortars. Adding those required a second lift. If, as often happened, the unit wanted to sling load a couple of M151s (Jeeps) with radios for C2 that might require more lifts as well. Depending on the complexity of the Ground Commander’s plan, the size of the target HLZ(s), and the flight time from pick up to drop off, the supporting air movement plans in and out can get quite complicated.

In that baseline scenario, a significant part of a Pathfinder’s pre-mission activities was that of a liaison between the air and ground elements. Deconflicting and synchronizing the supporting and supported efforts and balancing the real equities of both units. I did not think of it in those terms as a young Pathfinder. I just knew it was my job to help work the shit out so that the mission could be successful. Another large part of our mission was simply reconnaissance – again, a common infantry small unit tactical task. For example, depending on the tactical situation, a couple of Pathfinders might get dropped off by an OH58, move cross-country, survey (recon) the proposed HLZ and recommend by radio any adjustments to the air or ground plans. If the initial threat level is higher, the Pathfinders can insert with a Scout Platoon or other element to get eyes on and establish some level of initial security of the HLZ. Or, if complete tactical surprise is deemed more essential, Pathfinders come in with the lead bird of the first lift to provide real-time ground to air contact for the follow-on lifts.

We were more than capable of doing other, more diverse, and less traditional, missions as well. We were the Aviation Battalion’s de facto Downed Aircraft Recovery Team (DART) – although I do not remember us using that term. We responded to a couple of real-world crashes. One with casualties, one with fatalities while I was there. Plus, we flew out to secure a number of aircraft that had to land away from home station for maintenance issues until a maintenance team could get to them cross country. We always kept our LCE and other gear staged in our team room – much like firefighters – in case we got a call out. The two “Attack Companies” of the Battalion were based at a different Airfield in Giebelstadt. They were the first in Germany to field Cobra Gunships with TOW missiles. We participated in portions of an “Aero-Scout” experiment for their future employment as tank killers. The concept involved the OH58s dropping us off where we could select and observe a potential engagement area and then call in the Cobras when there were targets available. The ground part did not work out, but the OH58’s partnership with the Cobras was codified and continued.

We were also adjunct instructors for the 3rd Division’s Primary Leadership Development Course (PLDC). About every six weeks, we had the students for two days of Rappelling Training. On day one we did a ground and tower train up and on day two the helicopters. This was a win/win situation for the school cadre, the students, for us, and the Battalion. Fast Roping had not been invented yet, so rappelling was the preferred technique to get people – including Pathfinders – on the ground in places where the helicopter cannot land. The pilots had to certify on the skills involved as did we. Frankly, there were more pilots than Pathfinders and after we had practiced a couple of times each, we got really tired of doing it over and over to train the pilots. So, the PLDC students were perfect training aids. They got a new experience, the pilots took turns getting trained, and we made better use of our time practicing our “Rappelmaster” skills.

And, we were even involved in some missions with potential operational and strategic level impacts. Tactical nukes were more integrated into our Theater Defensive Plans during the Cold War in Germany than I think most people realize. When I was in A/1/15th Inf (75-76) we did several live ammo load outs to provide security for convoy deliveries of 155 and 8? Howitzer nuke rounds. Presumably, all the rounds we delivered to notional firing sites and then returned to storage were dummies – but we never knew for sure. It was the only time we wore Flak Vests, and the mission was taken very seriously while I was there. Lance Missile Batteries (Nuclear Capable) had organic infantry platoons to provide full time security. One of the missions of the 3rd Aviation Battalion was to deliver 12Es and their Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM) package(s) to the detonation site(s) in the Division’s sector. Certain aircrews had to certify for that mission. The Pathfinder Detachment I was part of was involved at both ends and we practiced that drill with the Engineers on a regular basis. Only those with a Secret Clearance or higher were allowed to participate. The sites we practiced on were not the actual target sites. Those were TS and only the most senior Engineers supposedly were privy to that information.

All of that is not to say we were well resourced in every way. A Divisional Pathfinder Detachment was supposed to have 14 soldiers led by a 1st LT OIC and a SFC NCOIC. For some administrative reason they were not coded as Team Leader or Team Sergeant – but that is what they were. And three 4-man Pathfinder Teams, each led by a Staff Sergeant. When I arrived, there were six of us. One SSG, two Sergeants, and three Specialists. Three months later we had dropped down to 4 people. That was unsustainable. In the 28 months or so that I was there, we had only two NCOs arrive in the “normal” way. One was a SFC who had just been cadre at the Pathfinder School at Benning. The other was a Sergeant out of the 101st Pathfinder Company. Both had “pinpoint” orders to our Detachment. Two examples of the Pathfinder Mafia at work.

Most infantry soldiers E-6 and above, and most Officers, came to Germany on those kinds of orders – already wearing the patches of the units they were going to. Those units usually met them at Rhein Main Airport in Frankfurt and took control of them almost immediately. However, E5s and below were almost always “Europe Unassigned” and spent several days at the Theater Replacement Detachment at the Airport before they were divvied out to the Divisions or other major units. We decided to take advantage of that loop hole. With our Battalion leaderships’ tacit approval, we would drive to the Rhein Main terminal and watch as Army chartered commercial airliners unloaded. If someone showed up with no patch, bloused jump boots, and an infantry blue cord we would approach them for a hasty interview/selection process. Mostly, “hey, how would you like to be a Pathfinder?” If we liked their answer, we grabbed their duffel from the baggage carousel and shanghaied them to Kitzingen.

Once there, out Battalion S1 would cut them orders assigning them to one of our unfilled slots. Basically, reverse pinpoint orders. Usually, we netted maybe one guy each visit, but once we picked up two – one from each of the Ranger Battalions. That way, in a few weeks, we got healthy with 10-11 assigned. When one guy would get ready to PCS, we would just make another trip or two to get his replacement. We ended up with 3 Ranger qualified guys and 2 SF qualified, but only the two NCOs I mentioned who came to us from Stateside Pathfinder units were school trained Pathfinders. The rest of us had to OJT. Because of that fact, technical and tactical training and mandatory pre-mission rehearsals to a high standard was a constant. We were all conscious of our “elite” status and we took it seriously. People inside and outside our chain of command were watching our performance all the time. I personally felt challenged every day to keep up with everyone else on the detachment and maintain the same standard of excellence.

I will give one example of the team ethos that I am talking about. In the summer of 1976, the 3rd Division held an Expert Infantry Badge (EIB) Test in the Kitzingen Training Area. In those days, it was common for each Infantry Battalion to send 40-45 candidates to the Test Site and they could expect to earn a half dozen EIBs at the end. It worked out that way that year. We sent 6 candidates – everyone who did not already have an EIB. Four of us – myself included – earned the EIB. The other two guys missed it by one task each. It was a pretty impressive showing and was noticed by leadership up to the Division level. Our Battalion Commander, who was an Aviation qualified Artilleryman IIRC, liked to brag that his Aviation Unit had earned almost as many EIBs as an actual Infantry Battalion. Even now, I attribute that performance to individual and collective motivation more than talent. None of us wanted to be the one that let the team down and performed accordingly.

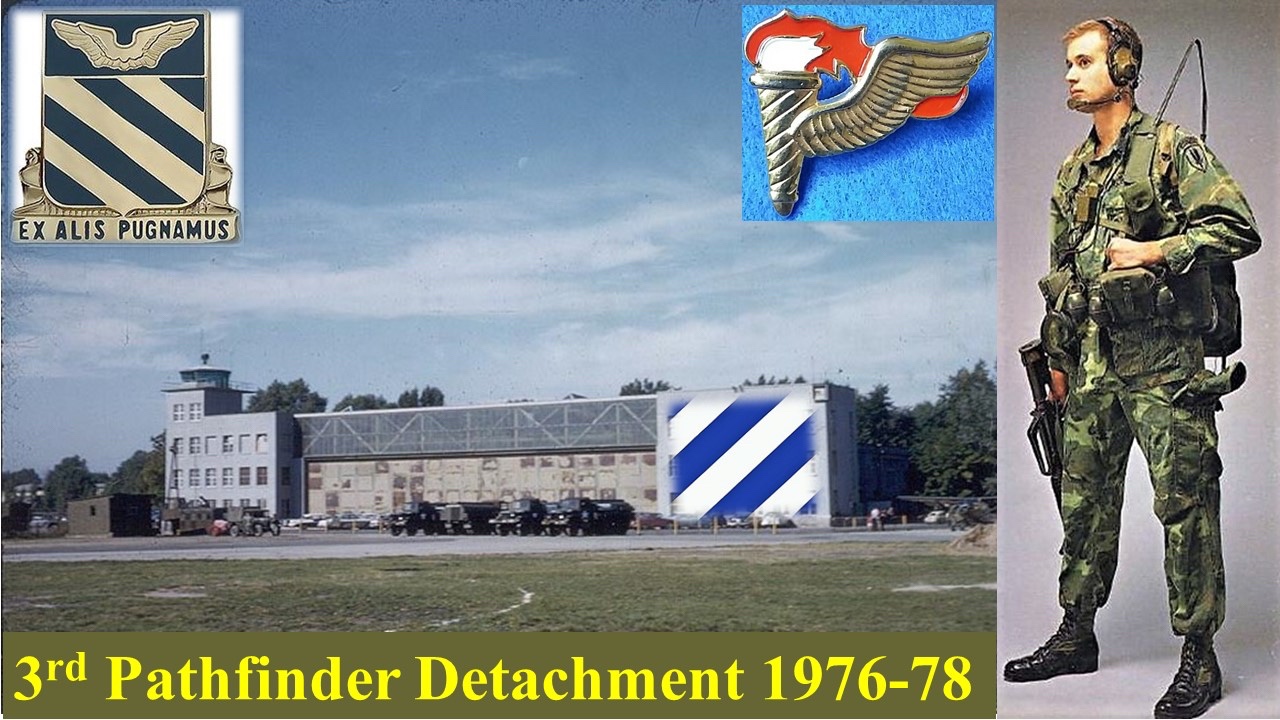

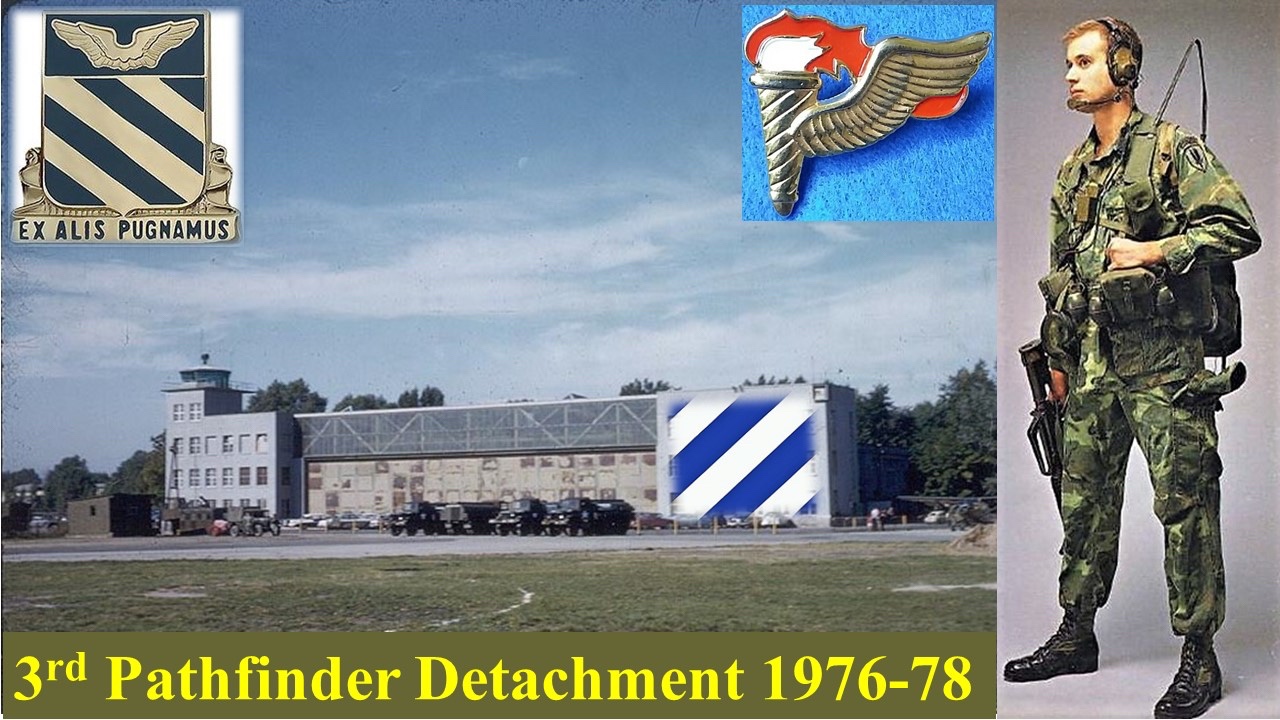

Let me explain the picture I put together and attached (above). On the top left is the DUI or Crest of the 3rd Aviation Battalion. On the top right the Pathfinder “Winged Torch” Badge. The picture of the role player on the far right is supposed to represent a Pathfinder in Vietnam circa 1970. That is what we looked like when we were working. We were authorized and wore the ERDL Jungle Fatigues. They were supposed to be “field uniforms” only – not to be worn in garrison. We cheated on that rule all the time. The weather had to be bitterly cold before we would cover up with OD Field Pants and Field Jackets. Yes, sometimes we froze our asses off, but we always looked good doing it. The ERDLs were issued, but we had to get Jungle Boots, OD Patrol Caps, and Kabar Knives from Shotgun News. We wore M1956 LCE loaded with Smoke Grenades, VS 17 Panels, and some of the same Survival Gear that the Aircrews carried. We almost always had a radio on our backs when working. The Pathfinder mission is comms heavy, so we actually had two radios (PRC 77s) assigned for every man and even had the same radio headset the model is wearing.

The building featured in the center of the picture is emblematic of my time with the Pathfinders. It was an old Luftwaffe structure. The picture was taken in the 1960s but it was the only one I could find on line that showed the face of the building. As the reader can see, the Airfield Control Tower is on the left side. Flight Operations for the Battalion was on the first floor on the right side. Whoever took the picture is probably standing on the near edge of the runway which ran parallel to the building. While not clearly visible, a taxiway runs along the left of the picture from the runway to the building. Almost all of our missions started and ended in front of that structure. About a quarter of a mile to the left, while coming back from a mission early one night, I rode a Huey in that lost engine power and auto rotated into the dirt just off the far end of the runway. The skids were crushed and the bird belly flopped into the ground, but we all walked away. Good times.

I met 5-Star General Omar Bradley in front of that Building. He was in his 80s at the time. Apparently, he was never technically retired. He had an SSG Enlisted Aid who pushed his wheel chair around. He was physically frail but his mind was still sharp and several of us talked with him for about an hour before an Army fixed wing aircraft showed up to take him away. It was an honor. I saw the first A10 to visit Europe there in 1976. The Air Force sent one bird with a very photogenic pilot and ground crew to show off the new plane to the US Army and our allies. It was supposed to be proof positive that the Air Force took the Close Air Support mission and Airland Battle Doctrine seriously. The plane did a one bird airshow over the Kitzingen Airfield and then taxied up to the building so that we could gawk at it. I tried to steal a dummy 30mm round but they caught me and took it back.

Reference back to the picture, on the far right I superimposed the 3rd Division Patch. That is because our Pathfinder Detachment painted that patch on the building in 1977. I just could not find a picture of it. We got the job because we had to do the top part of it by rappelling down the side of the building. Yes, the right side of the building had just as may windows as the left side. We just painted over the windows. I doubt if anyone was ever able to get any of those windows open again. Getting the job done was a weeklong chore and I managed to get myself in some trouble before we were done. But I will save that story for another time. In fact, there is a lot more to the saga of that Detachment and that time but those can wait too. I have been talking about the past, but I am truly trying to make a point that is relevant to the future. I want to make the case for bringing Pathfinder units back ASAP.

Recently, I traveled to Fort Campbell for the annual 5th SF Group Reunion. However, when I got on Post, I stopped first at the Air Assault School (AAS). I spent about 40 minutes with the school XO and several of the cadre NCOs. Specifically, I was looking for some answers about the status of Pathfinders in the Army since the deactivation of the last units (2017) and the closing of the school at Fort Benning (2020). I admit that I am still confused about the Army’s thought process on the subject. It seems that the proponency for Pathfinder training was passed to AAS without much specific guidance. AAS has dedicated cadre that focus on teaching Pathfinder skills, and awarding the Torch, through Mobile Training Teams (MTTs). Not long ago, SSD had an article about one that happened in support of the National Guard. I believe it was at Fort McCoy. They also do a couple each year at Fort Bragg.

That is all positive. Except, the Army clearly has no real institutional interest in the program. Units apparently select candidates for these classes based only on local Commanders’ criteria. The Army has not even specified any target density for Pathfinder qualified personnel, i.e., at least two per Rifle Company for example. When I was in the Infantry in ancient times, the S-3 Air/Deputy S-3 and S-3 Air NCO slots were routinely filled by PF qualified people if available. Of course, there were more Infantry Pathfinders being produced each year back then. No doubt, the Pathfinder Cadre at AAS are true believers in the Pathfinder mission – as they should be. They were happy to talk about it and hope someone can reinvigorate and reprioritize the program soon. I do too. As a side note, the school is sending multiple Air Assault and Pathfinder MTTs to Alaska to jump start the rapid transition of the 11th Airborne’s Stryker Brigade to Air Assault status.

Obviously, I am proud of my time with the Pathfinders. I know now, better than I knew then, that as a unit we consistently punched well above our weight. We set a high standard of excellence and did everything asked of us with consummate professionalism and elan. Moreover, I think Pathfinder skills are still highly relevant to the Army; both on an individual basis and in terms of eventually reactivating dedicated teams focused on the Pathfinder mission. Perhaps, I am just waxing nostalgic and Pathfinders and other small specialized units like Long Range Surveillance (LRS) teams – deactivated along the same timeline as the Pathfinder units – do not matter now that we have drones, etc. After all, some might say, the Horse Cavalry went away when modern mechanized warfare made them obsolete. That might appear to be a valid point, except, the Cavalry mission clearly did NOT go away. Sure, they changed their mounts from equines to motorized vehicles. They evolved, adopted new tools, updated techniques, and found new ways to do their mission. Indeed, I think – and the Army seems to agree – that Cavalry units will need to constantly change, but they still have a vital mission and are here to stay.

I took the following quotes from Army guidance put out at this year’s AUSA Convention in the order they were presented. The Army wants to:

“Acquire sensors to see more, farther, and more persistently than our enemies.”

“Concentrate highly lethal, low-signature [emphasis added] combat forces rapidly from dispersed locations to overwhelm adversaries at a place and time of our choosing.”

“Deliver precise, longer-range fires as part of the Joint Force to strike deep targets and massing enemy forces.”

“The U.S. Army relies on cohesive teams that are highly trained, disciplined and fit to fight and win [emphasis added].”

To me, that sounds like Pathfinders and LRS units – if they still existed – would already be examples of exactly the kind of capabilities that the Army is talking about building. To borrow from the “SOF Truths,” exactly the kind of competent force structure that cannot readily be built after emergencies occur. Bottom line. In my professional opinion, both LRS and Pathfinder unit deactivation decisions were ill informed and involved an over confidence in the same false assumptions about the “hi tech” future of “hybrid” or “near peer” warfare that the Army is infamous for getting wrong all too often. A well trained and motivated human is still the most capable all-weather, all-terrain, multifunctional, intelligence gathering sensor AND formidable full spectrum fighting instrument on the planet. As I have learned many times during my career, a team of those kind of people can be practically unstoppable. And that is not going to change anytime soon. Even in the 21st Century, People are still much more important than hardware!

First In, Last Out!

De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.