The history of today’s largest First Responder Distributor, GALLS®, started as one immigrant’s dream of America.

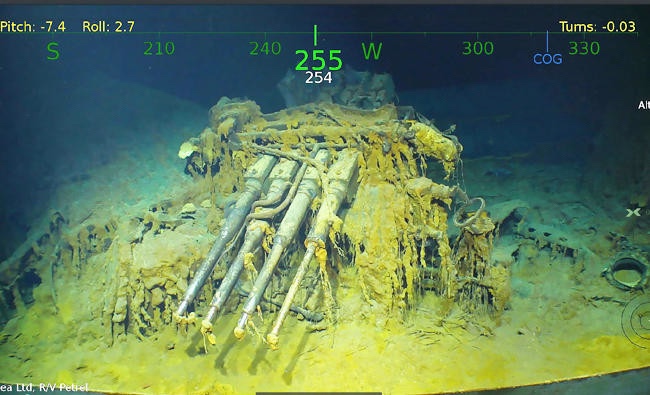

The Peddler was for many rural Americans, the only way to shop.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Lexington, Ken. (April 2021) – GALLS® is today the largest leading distributor of law enforcement and 1st responder apparel, gear, and equipment with over 100 locations, 300,000 sq. ft. of distribution, and 1,500 employees. Although its origins were modest compared to the size and breadth of the organization today, the founding principle is as relevant now as it was when Phillip Gall took a wagon laden with household ware into the hills and hollers of Kentucky at the turn of the 19th century.

“Phillip Gall was the epitome of the American dream come true,” Mike Fadden, CEO of GALLS Inc. said. “As an immigrant in a new country, he found a unique niche to call his own, and through his steadfast pursuit of building long-lasting customer relationship, was able to turn a ware-laden wagon into a very successful Lexington, Kentucky-based family business.”

As an immigrant from Lithuania, Phillip Gall came to America with a dream of finding freedom and opportunity for his family. Settling in Lexington, Kentucky with his wife and son, Isaac, Phillip traveled the backroads of Lexington’s surrounding hills peddling household items such as cookware, sewing supplies, and tools. Phillip Gall visited his customers’ homes, tucked away in the woods, or standing alone surrounded by farmland, that every visit was special. He developed close relationships with his customers, seeming to know what they wanted and how to turn every exchange of their hard-earned money for goods into a special occasion. Phillip Gall brought his own customer service expertise to the Kentucky hills.

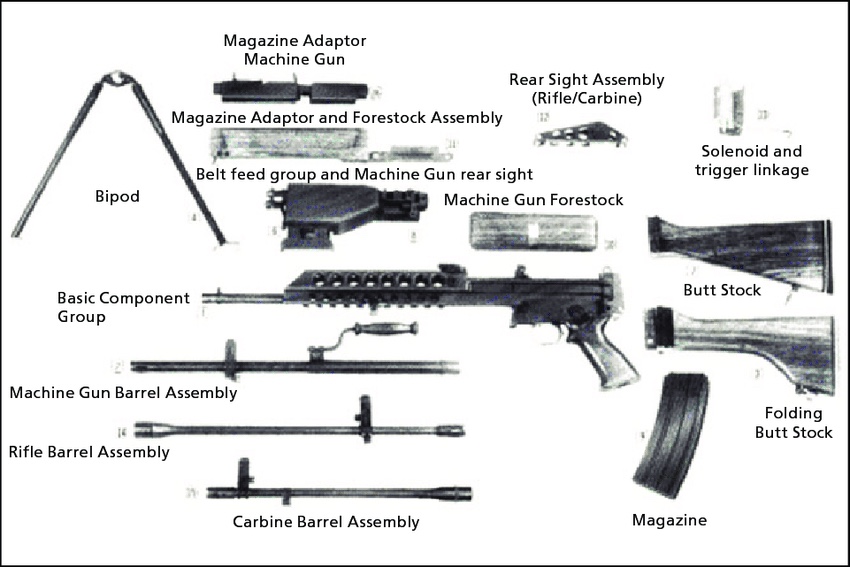

At the turn of the 19th century, Isaac, now a grown man, with his father, opened a second-hand store on Water Street in Lexington. Eventually, the second-hand store transitioned into a pawn shop, which eventually transitioned into a retail store including outdoor camping equipment, firearms, and police gear.

Phillip Galls’ store continued to meet the needs of their customers, whether it was moving the store to better locations or including products that their customers were seeking.

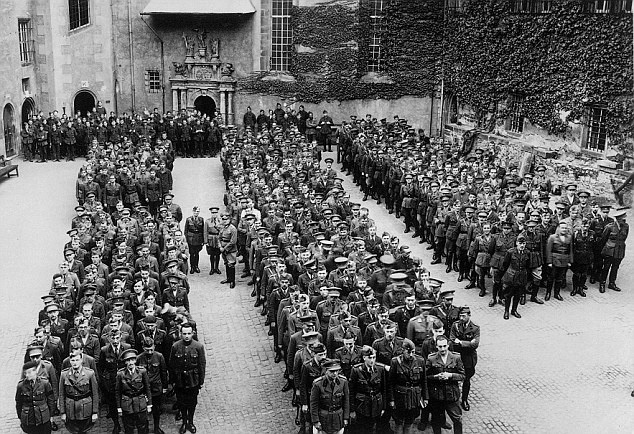

Sidney, Isaac’s son, grew up spending available time at Phillip Gall’s storefront helping out with everything and anything that was needed to service their growing customer base. It was a natural move for Sidney after he came home from serving in the war, to come into a partnership with his father, Isaac. During his tenure at Phillip Gall, the storefront moved from Water Street to West Main Street in 1972.

“During the third generation’s tenure of the Phillip Gall store, Sidney had developed both sides of the business, the outdoor and the law enforcement, as far as it could go within the confines of its location and their business model,” Fadden continued. “Times were changing and Sidney found within Alan Bloomfield, the potential to concentrate on one part of the business and relinquish the other part.”

In 1983, the Phillip Gall store sold off the police equipment and firearms part of the business to a young man who had also grown up in the storefront retail business in downtown Lexington. Alan Bloomfield’s parents owned a women’s department store and the retail business was in his blood. After the purchase, Phillip Gall was called Phillip Gall Outdoor & Ski and continued to serve outdoor enthusiasts. The police part of the business, now operated by Alan Bloomfield, was renamed Galls Inc. Alan Bloomfield hit the ground running, sending flyers to police departments offering specials on everything from guns to uniforms. During Bloomfield’s ownership, Galls Inc. became a national and international supply house for police, EMS, fire, and first responder equipment and the largest mail order and catalog house within that community. Within five years, the Galls Inc. Catalog won the National Catalog Association’s “Catalog of the Year.”

“Bloomfield was a legend in the catalog business. He took a relatively small mom-and-pop cop shop and turned it into one of the largest and most dynamic police and emergency equipment suppliers in the world. He was very much a visionary and saw outside the borders of Lexington and by building the Galls Catalog and mail-order business extended his product line offerings to law enforcement across the country,” Fadden remarked. “By 1995, Bloomfield had taken Galls Inc. from a 4-person, family-based company to a 250 employee-based distributor powerhouse. And he felt it was time for him to step aside.”

Aramark, a company founded in Philadelphia in 1936, provided uniform services, as well as food and facility service to clients in the healthcare, education, business, prisons, and leisure industries, purchased Galls Inc. in 1995 and quickly brought the catalog giant into the digital age. Within two years, Galls Inc. had inside and outside sales force to facilitate serving their growing law enforcement customer base. The new sales force was able to adapt to the current conditions and needs of the community. By 1999, Galls added a new sales partner with the launch of Galls.com allowing existing customers to interface with Galls and attracting new customers with their state-of-the-art website.

“Galls is changing rapidly during these years. The rapid growth included more service centers, more employees, and new technologies. At the same time Aramark purchased Galls, I came aboard Aramark,” Fadden said. “Little did I know at the time that my future at Aramark would put me in a leadership position at Galls. Meanwhile, my focus is primarily on the direct sale and rental uniform side of operations at Aramark. Those twenty-five years, in a variety of leadership positions, became critical stepping stones for my future position at Galls.”

CI Capital, a private North American investment group, purchased Galls Inc. in 2011 and began an accelerated program of growth and acquisitions including some of the top equipment and uniform vendors such as Quartermaster, Blumenthal Uniforms, Muscatello’s, Patriot Outfitters, and Red the Uniform Tailor, to name a few. As part of their aggressive growth platform, Galls continued to streamline processes within their company, and in 2011, eQuip, an online uniform and equipment procurement and management software platform, was launched.

“When a company is in serious acquisition mode and undergoing explosive growth, it is primarily focusing on building its infrastructure and streamlining processes such as accounting, distribution, sales, and marketing. It’s an inward-focused style of management, and although necessary for the company to grow, customers can start to feel as if they are no longer priority number one,” Fadden continued.”

In 2018 Galls, again changed hands when CI Capital Partners sold the company to Charlesbank Capital Partners based in Boston and New York. Within the next several years, Galls accumulated six more uniform and police equipment companies and a change of leadership when Mike Fadden became the new CEO of GALLS in June of 2020.

“Up until the past couple of years, Galls was still a traditional catalog-style company with a smaller B2B mindset in which either agencies came to us or our sales team drove sales to agencies,” Mike Fadden explained further. “Galls was this large company, now comprised of many smaller companies, across the country doing business their way. Unfortunately, in all of this massive growth, something very special was lost, something I think Phillip Gall would instantly recognize; the personal relationship with the customer was beginning to suffer.

As we enter this new decade, businesses are facing increased competition from outside and it is my imperative that we at Galls will always lead when it comes to outstanding customer service. That doesn’t just mean a pleasant voice on the other end of the telephone, but finding ways to provide efficient, cost-effective, and personalized service to our customer base. When I came aboard, Galls already had some of these service drivers in place such as eQuip, which allows our customers to manage their uniform and equipment purchases and uniform allotments. It gives them power and confidence over their budgets they never had when dealing with outside sales reps. What I found in my first 90-days were often small errors, whether a misshipment of product or delays and backorders due to the complicated order processing we had. It was literally dying from a thousand small cuts.

First things, first. We needed a central location to receive customer complaints, suggestions, or compliments and that box literally became my email address. We have been including a small card, a gesture, to our customers in every shipment, to let them know Galls IS listening and we want to know the good, the bad, and the ugly about our company. Since this out-reach program began, we have accumulated enough data to understand where our strengths and weaknesses lay and to act on them.”

Fadden and his executive team drove significant changes to the company’s IT structure to allow greater transparency between departments, increase efficiency, and speed up the process from initial ordering to delivery, thus shortening the duration while eliminating waste and cost overruns. In February of 2021, “Chief to Chief,” an email newsletter for agencies’ executive management was created. The monthly newsletter features a video of Mike Fadden, CEO of Galls, talking directly to the email recipient and encouraging an open dialog between one Chief to another. Again, Mike’s email box has been inundated with praise, suggestions, and some complaints, but Mike and his team compile all results and present changes to the company that has, in a few short months, already benefited customers and Galls’ employees.

“I think Phillip Gall could walk into our headquarters and not only be amazed at what he started but be proud of what Galls’ is doing today, in respect to building the trust and loyalty between our company and our customers,” Mike Fadden concluded. “He never lost sight of the importance of excellent customer service and it helped him build his dream, the American dream. It is our responsibility to continue to build on that tradition because superior customer service is one thing that never goes out of style.”