> When war broke out in the Persian Gulf, McRae Footwear shored up its workforce to deliver a new product. The desert boot was designed to stand up to the arid climate and sandy terrain of the Middle East.

Keeping out the heat

BY JULY 1990, times were tough for McRae Industries. The Cold War was over, military spending was down, and Defense Department demand for combat boots had ground to a halt. To weather the financial storm, company founder and CEO Branson McRae laid off nearly half of the company’s 287-person workforce and began to pursue other lines of business. It was the first furlough since McRae Footwear began making military boots in 1967.

“Many in our workforce had been with us for more than two decades,” says Victor Karam, who at that time headed up McRae’s footwear division. “Sending them home was heartbreaking.”

“No one wanted to see the U.S. in another war. But we took great pride in knowing these boots would make life better for our troops.”

— Victor Karam, Director, McRae Industries

Responding to the surge

Just a month later, war broke out in the Persian Gulf. In response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, the U.S. joined 38 other countries in an allied coalition, and laid-off McRae Footwear employees returned to work. Their orders? To produce a new desert combat boot for American troops.

“The government called us up to Philly on a Saturday morning, ” Victor remembers. “We were given a contract to produce 250,000 pairs of boots. Desert Storm came so quickly that our country wasn’t prepared to supply boots suited for the desert sand.”

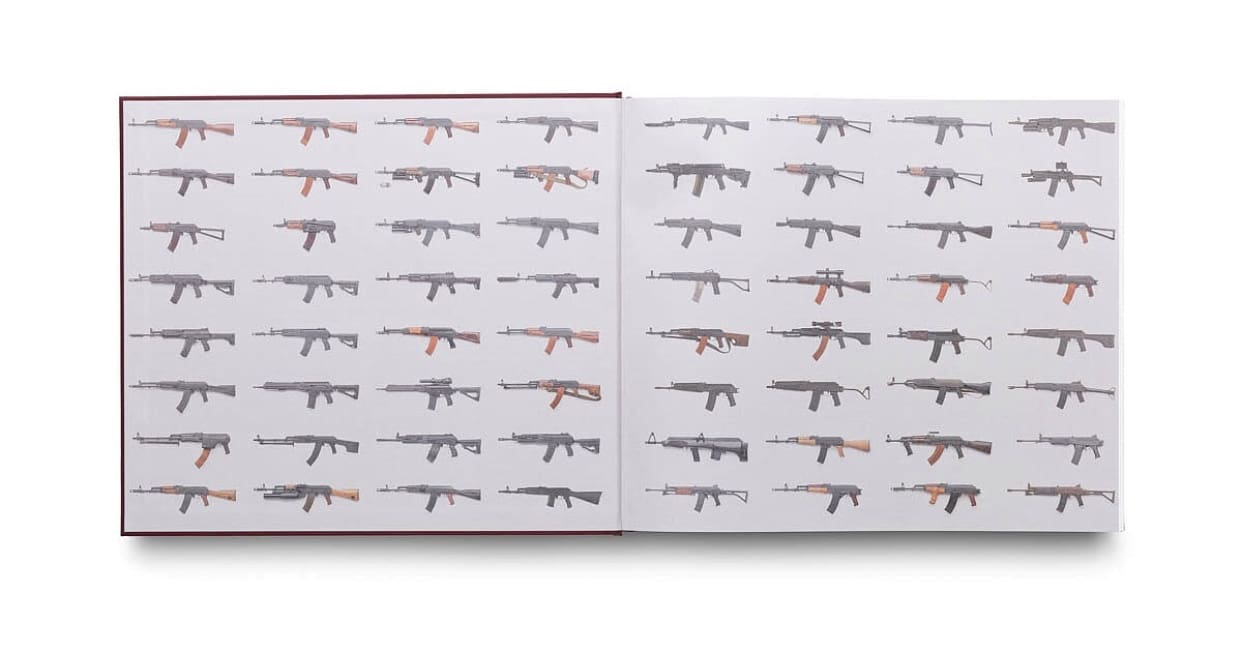

Desert combat: The Persian Gulf War called for new tactics-and new boots.

As troops were scuttled to the Gulf, McRae Footwear operated at peak capacity, churning out 200 cases of boots a day, 12 pairs a case, until the war ended in February 1991. To meet the demand, McRae Footwear also subcontracted with three other manufacturers and relied on its recently purchased western boot factory to help fill the government’s order.

Following Stormin’ Norman’s specs

The war required ground forces to operate in desert conditions – an environment not encountered by U.S. troops since the North African campaign of World War II. McRae Footwear was one of four companies the government selected to manufacture the new boot, again using vulcanization to attach the outsole to the upper and create a bond of invincible strength.

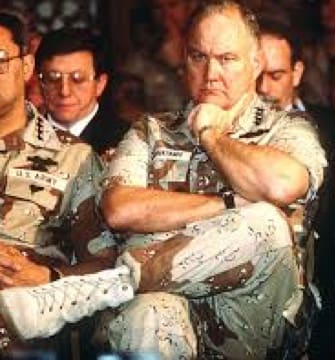

General Norman Schwarzkopf, U.S. commander in the Persian Gulf region, served as a key advisor in developing boot specs. He found that the black, leather, and canvas boot originally crafted for the Vietnam War was not suited to desert conditions. For example, drainage vents designed to keep out jungle moisture were letting sand in, and steel plates in the soles that protected against booby traps were retaining heat.

Along with removal of the vents and steel plates, Schwarzkopf’s specifications for the desert combat boot were many: tan fabric, padded collar, leather ankle reinforcement,10 speed-lace eyelets for easy tying and untying, and a Panama-sole tread pattern on the bottom of the boot, designed to easily shed debris. Boots were also insulated to provide extra protection from ground temperatures that could reach as high as 130 degrees.

Strict specifications: General Schwarzkopf set a high bar for designing the new desert combat boot.

After the war, the government continued to procure desert combat boots from McRae Footwear for ongoing operations in the Persian Gulf, as well as for use in other hot-weather regions. The original boot formed the basis for the hot-weather Army and Marine Corps combat boots of the 2000s. Today, the boot is produced using a rubber Vibram Sierra outsole, providing exceptional shock absorption and durability.

Mutual appreciation: Branson McRae meets President George H.W. Bush, who led the nation through the Persian Gulf War.

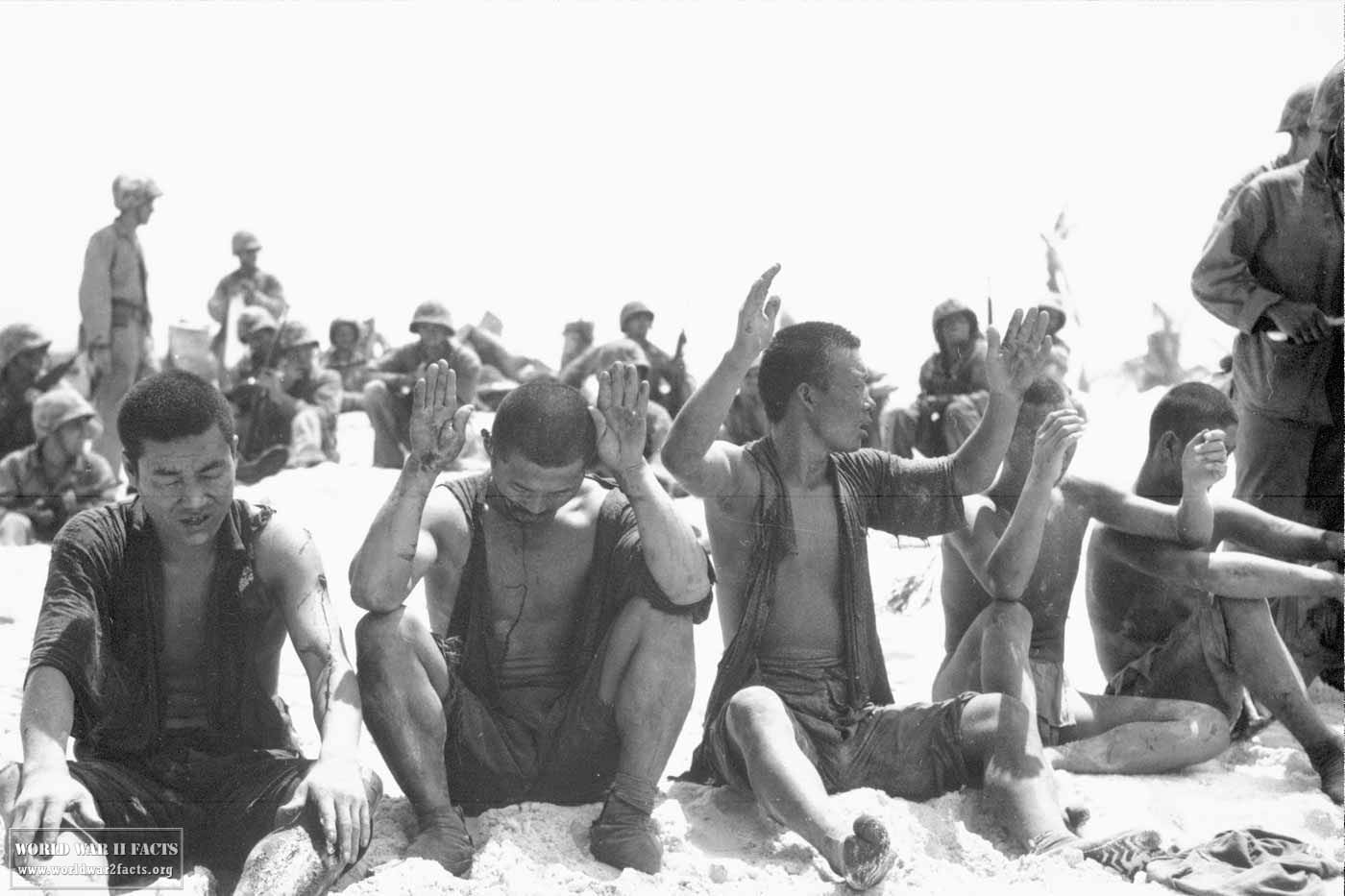

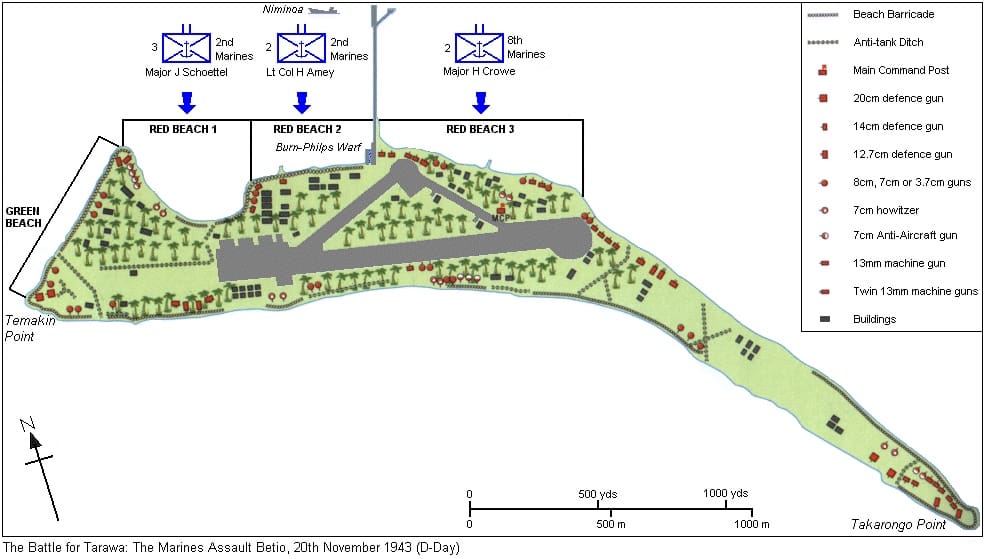

The first two assault companies, K and L, suffered over 50 percent casualties in the first two hours of the assault. The following waves were in even more trouble. Embarked in Higgins Boats, they had no choice but to unload at the reef due to the low tide. They had to wade ashore over 500 yards under heavy fire.

The first two assault companies, K and L, suffered over 50 percent casualties in the first two hours of the assault. The following waves were in even more trouble. Embarked in Higgins Boats, they had no choice but to unload at the reef due to the low tide. They had to wade ashore over 500 yards under heavy fire.