“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.”

– Sun Tzu

We are all shaped by life experiences – our own, and the example of others we have the opportunity to observe or read about. In terms of leadership development, I have tried to hammer home the following point many times. There is such a thing as a temporary duty position or acting rank; however, there is no such thing as temporary, acting, simulated or provisional leadership. Either you lead or you do not. “Do, or do not. There is no try.” as the great philosopher Yoda once said. In any case, for those of us who are privileged to lead, experience forges our personal “command philosophy.” That is how we fundamentally think of and approach leadership roles and responsibilities – formal or informal. As with many aspects of leadership, developing a personal philosophy is often a complicated maturation process over time. Therefore, I am going to concentrate on just one vital leadership trait or principle in this article – initiative.

Initiative in the military is often described as a binary choice; as in soldiers “taking action in the absence of orders.” If applied literally, that simplistic statement would seem to indicate that there is no option for individual or unit initiative after orders are issued? That cannot be right. I prefer to think of initiative as opportunities for positive action that soldiers – especially leaders – constantly seek out – with or without explicit orders. Moreover, when leaders find the chance, we are duty bound to seize those opportunities. Make no mistake, in peace and war, initiative must always be SEIZED by the individual; it cannot be requisitioned, allocated, disseminated, delegated, or preordained. Initiative starts with trust and confidence. Effective leaders who want to inculcate initiative into their organizations have to know and have confidence in themselves and trust in their subordinates.

Some say – and I believe – that asking for forgiveness [works] better than asking for permission. It certainly does speak to the essence of initiative. In practice, I have rarely found it necessary to ask forgiveness for exercising my initiative – within the context of accomplishing my assigned mission. I will share one clear example that happened early in my career. In 1980, I was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry (Wolfhounds) of the 25th Infantry Division stationed in Hawaii. This was before the “Light Division” initiative of the mid-to late 80s. We were a “straight leg” outfit. I was a promotable Sergeant (E-5) and was initially a Rifle Squad Leader in Alpha Company. That did not last long, a couple of months later, a slot opened for a TOW Section Leader in the Combat Support Company. I was TOW qualified, so I was moved over to that position.

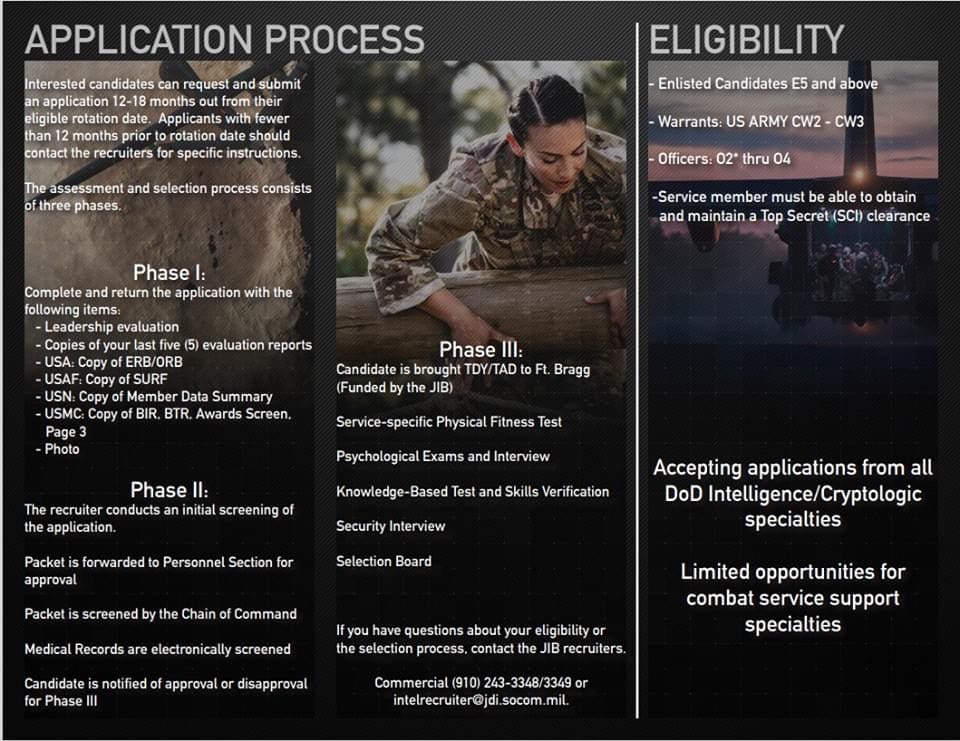

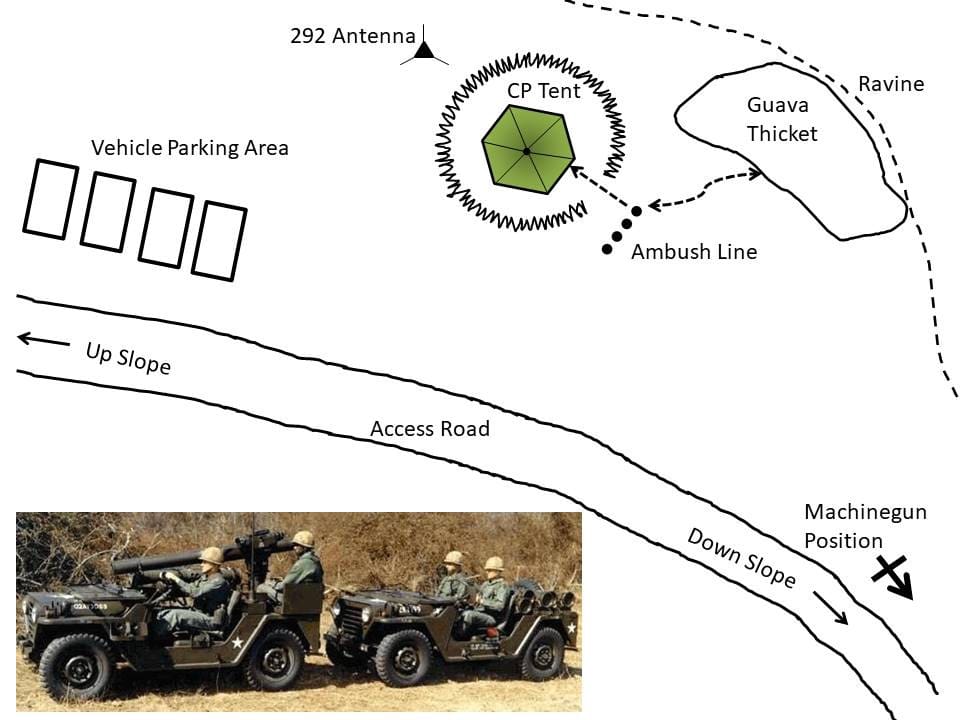

A TOW section consisted of eight soldiers in two squads (gun crews), four M151A2s, a.k.a. “Jeeps,” and two TOW systems. I have included a picture of one TOW squad for reference in the attached diagram below. Note: the picture is of the earliest version of the TOW system, circa 1974 and the vehicles are M151A1s not A2s. I had only 7 soldiers assigned but otherwise had a full complement of gear. In those days, TOW qualification was an additional infantry “skill identifier” not an MOS. There was a formal gunners’ course at Fort Benning but it never met the requirements in the field. Most soldiers, myself included, OJTed on the system at some point and were awarded the identifier after 90 days and a unit recommendation.

One day my Platoon Leader and Company Commander pulled me aside after morning formation in the Battalion Quad (Barracks Area). They told me that my Section had been “volunteered” to act as aggressors for an upcoming Battalion Command Post Exercise (CPX). I was to report to the Battalion Commander (BC) for additional guidance. I hustled over to the Battalion Headquarters and met the CSM first. He explained that the Battalion and Company level leadership would be going out to the Kahuku Training Area (KTA), in order to practice establishing CPs, troubleshoot communication systems, and work through the mechanics of issuing and disseminating tactical plans and orders. All of this was to get the Battalion C2 ready for the upcoming Team Spirit Exercise in Korea. As part of that preparation, a Rifle Platoon from Alpha Company had been tasked to provide security for the BN CP.

We went in to see the BC. He asked me if I had any questions about my mission. I asked only one question “is there anything specifically that you want me to do?” He said something to the effect that “No, the tactics are up to you. Your job is to take out the CP. Their job (the Platoon) is to stop you.” I said “Roger that,” saluted, and left. I received no additional guidance from anyone in the chain of command, nor did I seek it out. I had some thinking to do. I gathered my soldiers and we started to plan our patrol. The “patrol’ level order was about as far as any of us were familiar with mission planning. It was good enough. We had our organic assets of men, vehicles, radios, rifles (M16A1s) and even four PVS5 Night Vision Goggles for the drivers. We had no machine guns, but I could have gotten those from the arms room. I could have even scrounged up a few more men and trucks; however, I decided it was our mission and we would do it ourselves.

I knew what was expected. Everybody from the BC on down anticipated that we would drive to KTA, dismount, and “probe” the CP’s perimeter security. That was a losing proposition. The most we would accomplish would be to keep a platoon’s worth of soldiers awake for a few nights and still never get within striking distance of the CP itself. The platoon had the positional, manpower, and (overwhelming) firepower advantage in a fair fight. Moreover, although it was only a blank gunfight we were bound to take significant notional casualties. An inferior force bumbling blind into even a poorly prepared defense was tactically suicidal. I do not believe in suicide missions or training my people to get killed – even notionally. I wanted to win, I wanted to take out that CP, and I wanted my soldiers to have no doubt that we could do it. Therefore, a fair fight was out.

I pulled out the Ranger Handbook and looked up Raid first. I do not have that old 1970s version for reference, but the fundamentals have not changed much over the years. The 2011 Handbook says in part, “A raid is a form of attack, usually small scale, involving a swift entry into hostile territory to secure information, confuse the enemy, or destroy installations followed by a planned withdrawal. Squads do not conduct raids [emphasis added]. The sequence of platoon actions for a raid is similar to those for an ambush. …Fundamentals of the raid include: Surprise and speed. Infiltrate and surprise the enemy without being detected. Coordinated fires. Seal off the objective with well synchronized direct and indirect fires. Violence of action. Overwhelm the enemy with fire and maneuver. Planned withdrawal. Withdraw from the objective in an organized manner, maintaining security.”

It was obvious that a Raid in the traditional sense was out of the question. However, one of the fundamentals sounded particularly applicable to our situation, “Infiltrate and surprise the enemy without being detected.” So, I next looked up Ambush. “An ambush is a surprise attack from a concealed position on a moving or temporarily halted target. Ambushes are categorized as either hasty or deliberate and divided into two types, point or area; and formation linear or L shaped. The leader considers various key factors in determining the ambush category, type, and formation, and from these decisions, develops his ambush plan.” That was it. I had my Eureka moment. The CP was certainly a “temporarily halted target.” Therefore, if we could not successfully raid the CP, by God we would ambush it!

We did have some advantages. No one was paying attention to our planning so we were able to maintain airtight operational security (OPSEC). As the plan started to flesh out, my soldiers became more and more enthusiastic and understood the need for absolute secrecy. We also knew the enemy – well. I had been in the same company as had my Squad Leader. We knew the platoon selected and their leadership. The Platoon Sergeant was a Vietnam veteran (as almost all of the senior NCOs were). However, he was one of those guys who made it clear that he though peacetime training was bullshit and “you’ll learn the real deal when you get to combat.” Apparently that is how it worked for him in the Nam. In other words, while he probably knew how to do it right, he was a “half-stepper” who was not going to put much effort into this tasker. His squad leaders and even the Platoon Leader took their cues from him.

I was not a half-stepper and my men knew it and, unlike our enemy, we were highly motivated. A big advantage. I visited the S4 and picked up some scraps of training ammunition they had on hand. A can of 5.56 blank; about enough for each of us to have 5-6 loaded 20 Round magazines. A half dozen grenade simulators, several smoke grenades and four CS Ball Grenades. The Ball Grenades were designed for crowd control. When thrown, they broke apart and dispensed a chemical irritant in powder form. The grenade could not be thrown back, and the powder “contaminated” an area for an extended period of time. I expected to use them to deter pursuit if we had to break contact. During planning we figured out that we would need to divide into two elements. A mounted team with three vehicles and drivers and a dismounted ambush team of four. That was just enough.

Our most important advantage was that we knew where the CP was going to be established. The KTA is relatively small with highly compartmentalized terrain and thick vegetation. There was only a couple of places suitable for a BN CP and one of those was marginal at best. Therefore, because of the terrain constraints, we knew the location and the likely layout of the site. I had been there more than a few times. On one side was a guava thicket about 15 feet by 30 feet on the edge of a steep ravine (see diagram). We even knew how the platoon defense would be established in a horseshoe anchored on that ravine. Every unit that went out there for years had used the same fighting positions; including the machinegun position we expected to be sited to control the access road entrance into the CP. I had no doubt that the security platoon would take the easy way and fall into those same holes.

Our last advantage was our autonomous mobility. I could leave when I saw fit and had no requirement to make any additional checks with anybody. We left early the next Monday morning – day one of the CPX. The S-3 (Operations) shop and the S-6 (Communications) were just starting to load their vehicles when we left. I do not think anyone noticed our departure. We got to the CP site and confirmed our plan. My Squad Leader, acting as one driver, would take the vehicles one ridge line over and be prepared to support a hasty extraction of the ambush team if necessary. The vehicles moved out. The ambush team familiarized ourselves with the area (MG position, etc.) Again, refer to the diagram. I had two men crawl into the thicket and we confirmed that we would be concealed from view in that thick tangle of vegetation – even if someone got into the prone and looked.

We then rehearsed our ambush actions twice before crawling into the guava and establishing our Objective Rally Point (ORP). We were ready. Around mid-morning, the first people to arrive were the communicators and the NCOs from the S2 (Intelligence) and S3 sections. They went completely admin and stripped down to t-shirts to put up the tent and antennas. They surrounded the tent with one strand of concertina wire. Not for security, but just to keep people from running into the tent’s guy lines. They decorated the concertina with white cloth engineer tape to make the wire visible and to guide people to the single entrance. The security platoon arrived sometime around lunch. They were just as admin as the first crew. No one systematically cleared the objective area. They meandered out to their defensive positions a few at a time – and out of our sight. Then apparently, rather than improve their fighting positions, everyone took a late lunch of C-Rations. We could tell from the clanging of cans and the chatter. No noise discipline in effect until the BC, CSM, and S3 arrived around 1500 hours.

We waited quietly. No chow for us. The sound or the smell might give us away. We sipped water, took turns watching and slept. Just after dark, around 2130, all the Company Commanders arrived from their CPs for the Battalion Operations Order. It was time. They had walked themselves precisely into the kill zone of our ambush. I led the team out of the guava. We had put our ammo in our jungle fatigue shirts and left our LCE in the brush. We did not want to risk being hung up going out or back in. We lined up directly in front of the entrance and initiated the ambush with full auto fire from our M16s. A PFC by the name of Teague was the last man in the line. He had a special job. We had made up a dummy demolition charge and he was going to deliver it inside to complete the destruction of the CP.

Teague ran into the tent and then did some adlibbing. He told us later that he was startled when he went in because everyone was looking at him in shock. So he sprayed them with his remaining rounds and put the “demo charge” on the field table in front of the BC. We could hear clearly outside the tent as the BC asked, “Are you done, son?” Teague replied “No Sir, I’ve got a whole nother magazine!” So, he reloaded and gave them another 20 rounds before running back out. In the meantime, we had thrown smoke grenades behind us to block the view of anyone near the MG position or road and a couple more towards the vehicle parking area in case the drivers were looking. We finished with two grenade simulators for the demo charge detonation and then did a right face and crawled back into the guava. The ambush took less than 90 seconds. We waited for the reaction and the possibility we might be found out and have to run for it or slide on our asses down the side of the ravine behind us.

Not much happened for a while. The sounds had echoed among the trees and, unless one was looking in the right direction and saw the flashes, it would be unclear where the attack had originated. Indeed, standard procedure would be for soldiers on the perimeter to remain in place and scan their immediate sectors. Again, knowing my enemy, I had been certain that there would be no sentinels at the CP entrance or any quick reaction force (QRF) to respond. The platoon leadership would be trying to figure out what was going on before coming back to the CP and reporting to the BC. In the interim, the BC, Company Commanders, and the Staff had pushed on to issue the operations order. The S3 was a particularly loud talker and we could hear most of the plan as he presented it. After all, we were only about 35 feet away.

Eventually the briefing broke up and the S3 and Alpha Company Commander came out, actually moved next to our guava hideout, and yelled for the platoon leader. He showed up with the platoon sergeant for his ass chewing. He confessed that he did not know how we got past his people or got back out. But, he assured them, he would keep the platoon at 100% security for the rest of the night and it would not happen again. None of them considered for a moment that the aggressors might not be doing the expected or fighting fair. Without any immediate threat, we again started to take turns sleeping for the rest of the night. During the night there were several bursts of fire from the perimeter as the platoon stayed awake and engaged shadows.

We were not done. The next day we continued to rest and observe. I did not expect another big meeting on the second night, but I wanted everyone to know that the first night had not been a lucky fluke. We waited until about 0300 this time. Again, there was the occasional burst of random fire from the perimeter throughout the night. We crawled out in the same formation as the first time – this time with all our gear. It was time to leave. We initiated the ambush with our M16s and threw our remaining ordinance: simulators, smoke, and three of the CS Grenades right at the entrance of the CP. Then we faced left and moved deliberately to the road and downslope with me in the lead. I had the last CS grenade in my hand and was prepared to throw it at the MG position if necessary. I expected that the MG would be on the tripod and the crew would not be quick to turn it back toward the CP in any case. The CS powder would certainly distract them until we could get away.

As we came up to the position, someone – the gunner presumably – whispered, “What’s going on?” I whispered back, “The aggressors hit the CP again! Stay Alert! And, for God’s sake don’t fire us up when we come back!” “Roger that” came the reply. We kept moving at a walk. Fifty meters and less than a minute later we were entirely out of their sight and line of fire. We kept walking and, although I did not expect it, I threw the last grenade behind us on the road to deter any pursuit. I had carried one of our radios in my ruck for contingencies but had kept it off in the ORP. We turned it on and sent the codeword for extraction. The vehicle team had heard the explosions and the trucks got to the link up intersection just as we arrived. A 30 second accountability check and we were on our way back to Schofield Barracks. My soldiers were hungry but morale was sky high. We got back in time for breakfast at the Messhall. We spent the rest of the day cleaning up and slept that night in our own beds.

The next morning I was crossing the Quad after PT when the security platoon came back in. One of the Squad Leaders I knew pretty well stopped me. He told me that he was impressed how we got past them for two nights, but last night they had shut down every one of our attempts to infiltrate thru them. I could see that the guy was exhausted after 72 hours without sleep so I told him “good job” and went on my way. It appeared that not only had we taken out the battalion CP twice – killing most of the leadership the first time – but had also simultaneously managed to harass the rifle platoon and keep them awake for three nights without ever engaging them. I was proud of my men and how they handled the mission. No one had even fired a shot at us so we had zero compromises or casualties. Mission success in my book.

I cautioned my men to go with the “official story” that we had slipped stealthily through twice and did not get inside on the third try. I did submit some security suggestions to the BC a few days later including having the security element always go in first and clear the objective thoroughly, posting sentries at the CP itself (with night vision), and having some form of QRF. He asked me directly how we did it. Did we climb up and down the sides of the ravine he wondered? So, I told him. He said “I’ll be damned.” Then he looked at me and said, “I could have done without the CS. We had to move the CP entrance to the other side and they still haven’t gotten the smell out of the canvas.” I said, “Yes, Sir. We won’t use it next time.” As far as I know, the BC never shared that story with anyone else. I was never asked to aggress against the CP again either.

I suspect that the BC also made a mental note to himself to be more explicit in his instructions the next time he gave someone like me a mission. It is true that I had not given him exactly what he expected. In fact, I had given him something better than he originally wanted from me. I gave him what he actually needed – an honest and complete evaluation on the security posture of his CP. Simply probing the perimeter would have provided little useful feedback. The BC went on to validate our work by having his people apply my recommendations during Team Spirit and incorporated them into the CP SOP.

When it comes to initiative, there are a couple of “rules” leaders need to follow. If you are the subordinate, never ask for more guidance then you absolutely need to understand the mission and the commander’s intent. Always leave yourself some room for initiative. If you are the senior, never give any more guidance than you absolutely have to. That usually means only those essential constraints and limitations required to synchronize actions between units. Give your subordinates as much time and space as possible to exercise their individual initiative. Imagination, audacity, and initiative are always value added and powerful force multipliers. A wise leader encourages and harnesses that power. Good units develop bold soldiers at all levels who are never afraid to carpe diem.

De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.