Observations and Best Practices of The 6th Battalion, 56th Air Defense Artillery, National Training Center, Rotation 25-02

Download document here: No. 25-976, MSHORAD in BCT Operations [PDF – 565.1 KB]

Introduction: Defining the Role of Short Range Air Defense in the Brigade Combat Team (BCT)

Short Range Air Defense (SHORAD) is an inherently demanding mission set, requiring Air Defense commanders, leaders, and subject-matter experts to have a comprehensive understanding of air threats, and system capabilities, as well as an understanding of the ground fight for Air Defense units to meet their higher headquarters’ commander’s intent and end State.

The relationship between SHORAD units and the supported maneuver commander is a unique dynamic that requires detailed planning through the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP) to ensure there is a shared understanding, vertically and horizontally, for incorporation of SHORAD into the scheme of maneuver.

Since 2022, three Maneuver SHORAD (M-SHORAD) Battalions have been established, with two organic to division-level organizations. It is during this initial window of establishing M-SHORAD that lessons learned, and best practices must be captured at the National Training Center, and codified as actionable doctrine for the Air Defense force at large.

This paper describes both best practices and recommendations for M-SHORAD batteries in support of the Brigade Combat Team (BCT) and division, specifically regarding the role of the Air Defense Coordinator (ADCOORD), employment of Stinger and Counter-small Unmanned Aircraft System (C-sUAS) systems, and engagement authority within the division. The ADA Branch must continually examine the role of SHORAD and mission command dynamics to set conditions for success in future SHORAD implementation. This paper references the yet-to-be-published FM 3-01, dated 04 November 2024, to provide appropriate context for the National Training Center rotation 25-02. Charlie Battery, 6th Battalion, 56th Air Defense Artillery Battalion (C/6-56 ADA BN) was the supporting M-SHORAD Battery during this rotation.

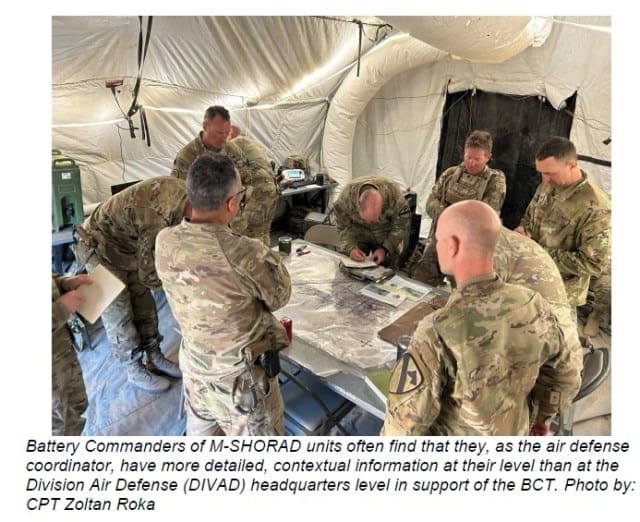

The Role of the Air Defense Coordinator

Battery commanders of M-SHORAD units often find that they, as the air defense coordinator (ADCOORD), have more detailed and contextual information at their level than at the Division Air Defense (DIVAD) headquarters when supporting the BCT. Enemy air avenue of approach, force protection capabilities, other Air Defense assets in the area of operation, local dynamics, and a host of other mission considerations are often better understood in real-time by the battery commander rather than their higher headquarters. In this relationship, immediate decision-making on detailed matters and specific actions is best executed at the lowest level, where the information and contextual understanding are timelier and more precise.

Throughout rotation 25-02, the C/6-56 ADA BN battery commander validated this concept through continual integration into the brigade plans and current operations (CUOPS) at the Main Command Post (MCP). It was critical that the battery commander had a holistic understanding of the brigade’s mission, and appropriately planned considerations for the battery to manage the execution of air defense operations. The most significant impacts the ADCOORD had were specific recommendations of task organization and command relationships (COMREL), synchronized efforts for the development of the unit airspace plan (UAP) to define Airspace Management requirements, and the early integration into MDMP and Intelligence Preparation of the Operational Environment (IPOE).

While C/6-56 ADA BN had a comprehensive task organization and COMREL going into the rotation, the nature of the fight required dynamic reorganization of the battery to optimize ADA assets in opposition to the air threats. Integrating the ADCOORD with the brigade S2, plans, and operations officer enabled the ADCOORD to inform the commander and adjust the task organization appropriately to ensure M-SHORAD coverage supported the identified unit or protected asset.

As the ADCOORD, the Battery Commander also influenced the specific type of command and support relationships within the brigade. This synchronization was achieved through the purposeful integration of the Battery Commander through the MDMP process, and the deliberate inclusion of ADA considerations in the brigade’s decision support matrix (DSM), enabling the tenets of Air Defense and Mission Command throughout the operation.

Of note, the most detrimental impact on the ADCOORD was the understaffed and undertrained Air Defense Airspace Management (ADAM) cell. Due to the naturally demanded requirements to provide real-time information to the MCP and CUOPS, there continued to be an increased expectation of situational awareness from the ADAM cell, especially considering the threat of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) and deliberate integration of M-SHORAD.

To help the ADAM cell manage the fight, the C/6-56 commander provided Soldiers from the battery. However, this resulted in “mission creep,” with the battery effectively serving as the ADAM cell, specifically regarding battle drills, TOC updates, and COP management. It is critical to the functions of the MCP, and supporting M-SHORAD Battery to ensure the ADAM cell is manned, trained, and equipped to enable command post activities with marginal, if any, augmentation from the battery.

While the draft of FM 3-01 does outline a battery commander as the ADCOORD to a supported Brigade Commander, it does not clarify the relationship of multiple SHORAD Battery Commanders to a single brigade.

Non-Dedicated Stinger Teams

In 2017, the Headquarters Department of the Army published HQDA EXORD 182-17 Implementation of Increasing Short Range Air Defense (SHORAD) To Maneuver Forces Initiative. The United States Army Air Defense Artillery School immediately began training various non-air defense Soldiers and units as part of this directive. Since then, units have struggled maintaining training proficiency and standards for gunnery programs within the BCTs and divisions.

In the case of rotation 25-02, approximately 24-man portable air defense systems (MANPADS) were issued to the BCT. However, it quickly became apparent that the operators of those systems were not integrated into the scheme of air defense. This included surface-to-air missile (SAM) engagement reports, MANPADS distribution plan, or the DSM to reallocate air defense assets. It was also unclear whether the operators were trained and certified on the weapons system, as the brigade did not maintain any centralized gunnery program.

While this may not be the case with every BCT or division, all units are required to understand the training and certification of Stinger operators for the proper planning and projection of ADA combat power. If it is the intent of the United States Army to increase the air defense capabilities within the BCT to non-air defenders, it is imperative for elements at the division and below to establish and manage a gunnery program.

Training circular (TC) 3-01.18 outlines the gunnery standards for both air defenders and non-air defenders; however, the current publication tasks the organic Army Air and Missile Defense Command (AAMDC) or delegated ADA Brigade Commander to oversee the program and establish a brigade standardization officer to evaluate battalion teams, training plans and training schedules.

It may be necessary to include a 14P, AMD Crewmember, Master Gunnery position, and the necessary equipment to divisions to provide oversight for evaluations and gunnery standards in line with TC 3-01.18 across the formation. The current TC only refers to Avenger Master Gunners but may be interchangeable with M-SHORAD Master Gunners based on the overlap of base knowledge of the Stinger weapon system. The Master Gunner position could be assigned to the Division AMD sections to support all division MANPADS gunnery, for both Air Defense and non-Air Defense Stinger teams.

While the draft FM 3-01 does charge the ADCOORD with providing oversight of AMD training and certification, the current TC is incongruent with the DIVAD construct within a division, including divisions that must maintain currency without a DIVAD to provide oversight. Until the training circular can better capture the current structure and requirement of non-dedicated air defense, it will likely be at the discretion of the division or BCT commander to determine the unit’s training strategies, standards, and training schedules.

In units without a DIVAD, non-dedicated MANPADS gunnery is even more problematic. In those cases, divisions maintain zero ADA commanders, with the division AMD chief serving as the senior air defender in the division and the ADAM air defense officer as the senior air defender in the brigade. In these organizations, there is even less capability to provide the necessary oversight to manage a MANPADS gunnery program in accordance with the current TC. It may be essential for the next iteration of the TC to shift to a MOS agnostic approach, enabling any organization or unit to establish MANPADS programs or source mobile training teams as necessary.

Counter Small UAS Systems and Employment

Much like the previously discussed MANPADS concerns, divisions and brigades lack the training proficiency and certification requirements associated with C-sUAS systems. While two divisions have been issued Smart Shooter, Modi, Bal Chatri, and Drone Buster, it is also clear that these systems have been either relegated to use only by assigned air defenders or lack any oversight, specifically in organizations that do not have a DIVAD battalion.

In those cases where a DIVAD is assigned to a division, air defenders show excellent proficiency when employing C-sUAS systems. However, the availability of personnel to employ handheld systems is limited, as the supporting ADA battery typically operates on their primary weapon system, the M-SHORAD Stryker. In cases where the systems are issued to non-dedicated air defenders, they generally are improperly employed due to limited training with the system.

The number of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) systems or other capabilities that are not programs of record is also increasingly challenging to manage. Systems previously seen at the National Training Center include, but are not limited to, MADS-K, BEAST+, Titan, SkyView, and Enforceair. Including these self-procured systems increases the training requirements and certification for each BCT. These systems are often challenging to manage from an emission control (EMCON) and spectrum management perspective.

As recommended with the MANPADS, it is a commander’s prerogative to ensure training and certifications are managed within a centralized standardization program. As of 17 September 2024, the Fires Center of Excellence, Directorate of Training & Doctrine released the Counter-small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Home Station Training Support Package & Administrative Guide. The UAS support package should serve as the base document for units for handheld and self-procured systems until the appropriate gunnery standards are established. However, based on the type of C-sUAS systems, it will likely not be a comprehensive training guide.

Short Range Air Defense Engagement Authorities

As M-SHORAD continues to integrate into maneuver elements, the ability to make timely and accurate engagements and manage airspace within a brigade or division becomes increasingly more complex. Key to this discussion is the level of control for SHORAD units, specifically the engagement authority.

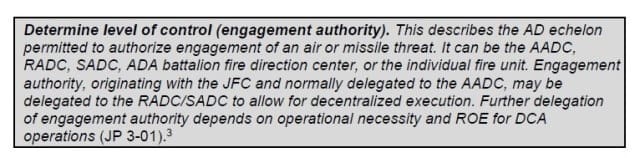

Joint Publication (JP) 3-01, Countering Air and Missile Threats states that while the engagement authority originates at the joint force commander (JFC) and can be delegated to the area air defense commander (AADC), and that engagement authority can also be delegated to the individual fire unit based on the operational necessity and rules of engagement (ROE) for defensive counterair operations.[2]

This level of autonomy will be vital to ensure that SHORAD units supporting the maneuver commander can make timely engagements to protect the force. The current draft of FM 3-01 states ADA commanders in divisions and BCTs control engagements using the ROEs, with engagements typically decentralized to the fire unit. However, this will still require a certain level of synchronicity to ensure engagements occur in line with the area air defense plan (AADP). Additionally, it will be necessary to establish engagement boundaries that consider the coordinating altitude (CA) for other airspace users and clearance of fires, forcing integration between the DIVAD and echelons above the brigade and division.

During rotation 25-02, C/6-56 ADA BN, in conjunction with the NTC higher control cell (HICON), refined the engagement authority to ensure that they met training objectives and best replicated real-world application. This was primarily accomplished through the deliberate planning and coordination between the Battery ADCOORD and HICON in line with the scenario-generated air threat and constructive division guidance.

The published rules of engagement considered declared hostiles, hostile intent, hostile act, and autonomous engagements and were subsequently published in the division order. In turn, C/6-56 ADA BN codified the brigade’s engagement authority for hostile air threats: “Stout VCs have engagement authority (EA) of RW and group 1-2 UAS. All engagements must be reported to ADAM/BAE and Nighthawk 6 at BDE Main. EA for FW and group 3-5 UAS is with BDE AMD Cell, Nighthawk 6, or BDE Main. All located at BDE TOC.

What was not detailed in the C/6-56 ADA BN plan was the CA. CA is a determining factor for engagements within a joint environment. In addition to the CA, the battery, in conjunction with the ADAM cell and brigade aviation element (BAE), needs to ensure that the appropriate airspace coordinating measure (ACM) requests are submitted as part of the UAP to create shared understanding between airspace users.

Observations from rotation 25-02 suggest the use of a low-altitude missile engagement zone (LOMEZ) to better define where SHORAD units operate, specifically for those elements maneuvering with the supported unit. For those SHORAD elements in a fixed or static location (MCP, airfield, brigade support area, etc.), a short-range AD engagement zone (SHORADEZ) may be more appropriate. However, these recommendations may change based on employment and mission requirements.

Additional coordination is required for a SHORAD unit when divisional assets identify a threat aircraft operating in the division area of operations but do not have the authority to engage the threat under the rules of engagement or weapons control status. This procedure needs to provide specific guidance to include potential SHORAD engagements above the CA, as the DIVAD must coordinate with the division Joint Air Ground Integration Center (JAGIC) for engagement authority in these cases.

Annex A to ATP 3-91.1, The Joint Air Ground Integration Center, outlines this process in detail.[4] What potentially requires an update is the Call for Defensive Counterair with Established Track, with the understanding that JP 3-01 and the pending FM 3-01 delegate engagement authority to the ADA commanders in divisions and BCTs using published ROEs.

To reduce the time to engagement, the JAGIC should develop a decision authorities matrix, or appropriate Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) to ensure they are delegated appropriate authorities to execute their functions organic to the JAGIC to facilitate these engagements. It is important to remember that these authorities must be consistent with the airspace control plan and the area air defense plan defined by the JFC and Joint Force Air Component Commander.

Conclusions and Implications for Air Defense

Air Defense and Maneuver Culture. SHORAD’s current and future missions require air defenders to understand short-range air defense and integration with the supported commander. This relationship, nested within mission command, will help necessitate the development of doctrine, unit operating procedures, military decision-making, and operations.

Additionally, it is the responsibility of the Air Defense proponent and doctrine to ensure lessons learned and best practices are codified in a way that is communicated back to the force, resulting in tangible changes to Army DOTMLPF-P. This includes adjustments to the programs of instruction within professional military education for officers, warrant officers, and enlisted Soldiers as early as possible within the ADA school. Future curriculum must address joint service interoperability, large-scale combat operations, and the increasing role of air defense in the division fight. Air Defense may need to leverage maximum attendance to the Stryker Leaders Course and the Maneuver Captain’s Career Course to bridge the knowledge gap between M-SHORAD and the maneuver force.

Leader Development. The DIVAD requires mature, independently operating company-grade leaders skilled in communications, critical thinking, and the ability to conduct leader engagement while integrating at echelon. Positions, such as the ADCOORD and ADAM cell officer, are crucial touchpoints to synchronize efforts with the supported unit. It is equally important for maneuver commanders to be educated on the air defense capabilities organic to their unit. Air defense leaders are ultimately responsible for educating the supported commanders and facilitating effective mission command in complex air and missile defense environments.

Realistic Training. Conducting realistic training that appropriately replicates the complexities of a joint and dynamic environment benefits the DIVAD and the division. Demanding home station training and combat training center rotations must push the Soldiers and systems required for real-world application to ensure units can meet the stresses of combat against agile and proficient advisories. It is the charge of unit master gunners, commanders, and standardization teams to ensure units are challenged with the complexities of large-scale combat operations.

[1] ATP 6-0.5, Command Post Organization and Operations, Headquarters Department of the Army, Mar 2017.

[2] JP 3-01, Countering Air and Missile Threats, 13 Mar 2024

[3] JP 3-01, Countering Air and Missile Threats, 13 Mar 2024

[4] ATP 3-91.1, The Joint Air Ground Integration Center, April 2019

By MAJ Julian Rodriguez, Center for Army Lessons Learned

MAJ Julian Rodriguez currently serves as the Senior Air Defense Trainer at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, CA. His previous assignments include 4-3 ADA BN as a Patriot Battery Platoon Leader and Battery Executive Officer; 82nd Division, Combat Aviation Brigade as the ADAM OIC; 1st Security Force Assistance Brigade as the brigade planner; White Sands Missile Range as the AMD Test Detachment Commander; and 30th ADA BDE as a Battalion Executive Officer and Brigade Operations Officer. MAJ Rodriguez’s civilian education includes a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from the University of Texas at Arlington, and a Master’s degree in Leadership Studies from the University of Texas at El Paso.

Photographer, Wilson Van Ness, 2024

Photographer, Wilson Van Ness, 2024