Introduction

The use of kayaks or canoes more broadly for military operations is nearly as old as the craft themselves. Inland and coastal waterways have served as arteries of commerce, migration, and conflict since antiquity. With the introduction of engines, human-powered watercraft largely faded from conventional military use, surviving primarily in sport, recreation, and a narrow but enduring niche: special operations.

This article provides a focused overview of the military kayak’s role from the Second World War to the present day. It is not an exhaustive history, but rather a snapshot of how a simple platform when paired with disciplined fieldcraft has enabled stealth, endurance, and access disproportionate to its size.

World War II: The Birth of Modern Military Kayak Operations

Early in the Second World War, British forces recognized the potential of kayaks for clandestine maritime raiding. One of the earliest and most influential proponents was Major Herbert “Blondie” Hasler, an accomplished canoeist who understood that small, purpose-trained teams moving silently along rivers and coastlines could strike targets inaccessible to conventional forces.

Hasler proposed a solution to a persistent operational problem: German shipping operating from the occupied port of Bordeaux, which had proven difficult for British Bomber Command to interdict. His plan envisioned a ten-man raiding force launched by submarine outside the mouth of the Gironde Estuary. From there, the team would paddle more than eighty miles during periods of limited visibility, emplace limpet mines on enemy shipping, and then evade by any means available, with the ultimate goal of returning to the United Kingdom.

Hasler proposed a solution to a persistent operational problem: German shipping operating from the occupied port of Bordeaux, which had proven difficult for British Bomber Command to interdict. His plan envisioned a ten-man raiding force launched by submarine outside the mouth of the Gironde Estuary. From there, the team would paddle more than eighty miles during periods of limited visibility, emplace limpet mines on enemy shipping, and then evade by any means available, with the ultimate goal of returning to the United Kingdom.

This mission later known as Operation Frankton became one of the most iconic special operations of the war and was immortalized in books and film under the title The Cockleshell Heroes.

Operation Frankton validated the concept of kayak-borne raiding and directly influenced the development of British maritime special operations doctrine. During this same period, multiple parallel kayak development efforts were underway in the United Kingdom, refining folding designs and techniques that would later inform the Special Boat Service (SBS) and allied units.

Operation Frankton validated the concept of kayak-borne raiding and directly influenced the development of British maritime special operations doctrine. During this same period, multiple parallel kayak development efforts were underway in the United Kingdom, refining folding designs and techniques that would later inform the Special Boat Service (SBS) and allied units.

The Pacific Theater: Operation Jaywick

Kayak operations were not confined to Europe. In the Pacific Theater, the Allied Z Special Force demonstrated the strategic potential of kayak infiltration during Operation Jaywick.

Six men, operating from three kayaks, infiltrated Singapore Harbor and emplaced limpet mines on Japanese shipping. The operation resulted in the destruction or serious damage of approximately 39,000 tons of enemy vessels.

Jaywick confirmed that kayak-based operations could succeed even in heavily defended ports and reinforced the kayak’s role as a viable platform for strategic raiding when employed by highly trained personnel.

Post-War Continuity: The Rhodesian SAS

Following the Second World War, kayaks remained in service with special operations forces in the United Kingdom, Europe, Africa, Asia and the United States. One of the most compelling post-war examples comes from the Rhodesian Bush War.

Following the Second World War, kayaks remained in service with special operations forces in the United Kingdom, Europe, Africa, Asia and the United States. One of the most compelling post-war examples comes from the Rhodesian Bush War.

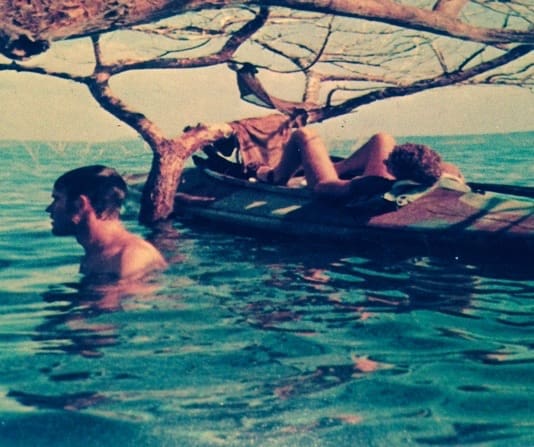

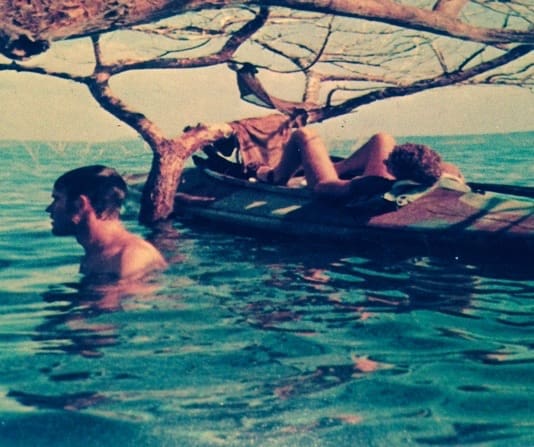

The Rhodesian SAS employed kayaks and canoes as low-signature insertion platforms along major waterways, particularly the Zambezi River and its tributaries. Among these missions, one operation stands out for its duration and austerity: a small SAS element inserted by kayak and operated entirely waterborne for approximately five weeks.

The patrol lived out of their boats, sleeping offshore in the kayaks or briefly ashore in concealed shoreline hides. During this period, they conducted persistent shoreline reconnaissance, surveillance of infiltration routes, and limited raids against insurgent logistics nodes, camps, and river crossings.

Kayaks enabled silent night movement, an extremely low visual and acoustic signature, and continuous repositioning without reliance on fixed bases, vehicles, or aircraft. This operation remains one of the most extreme examples of fieldcraft, endurance, and waterborne stealth in modern special operations history. Conceptually, it aligns more closely with Second World War SBS and Combined Operations Pilotage Party (COPP) missions than with later helicopter-centric SOF models.

Kayaks enabled silent night movement, an extremely low visual and acoustic signature, and continuous repositioning without reliance on fixed bases, vehicles, or aircraft. This operation remains one of the most extreme examples of fieldcraft, endurance, and waterborne stealth in modern special operations history. Conceptually, it aligns more closely with Second World War SBS and Combined Operations Pilotage Party (COPP) missions than with later helicopter-centric SOF models.

Cold and Littoral Operations: Pebble Island, 1982

In May 1982, during the Falklands conflict, British special operations forces again demonstrated the value of kayak infiltration. Prior to the raid on Argentine aircraft positioned on Pebble Island, a small SAS reconnaissance element conducted a covert insertion by kayak.

Launching at night from offshore, the team paddled in extreme South Atlantic weather to avoid detection. Once ashore, the kayaks were cached and the patrol transitioned to foot movement to conduct reconnaissance of aircraft disposition, defensive routines, and terrain.

Launching at night from offshore, the team paddled in extreme South Atlantic weather to avoid detection. Once ashore, the kayaks were cached and the patrol transitioned to foot movement to conduct reconnaissance of aircraft disposition, defensive routines, and terrain.

This reconnaissance directly enabled the success of the subsequent raid and reaffirmed a long-standing lineage of British waterborne special operations doctrine: small teams, operating independently, emphasizing endurance, precision, and stealth in austere environments.

Years later, during a training rotation at the Mountain Camp in Salalah, Oman, I had the opportunity to hear a firsthand account of this operation from Brumby Stokes, one of the four-man SAS team who conducted the paddle and reconnaissance. Hearing the details directly from a participant reinforced how demandingand how deliberately understated these operations were.

Pebble Island remains a textbook example of kayak-based SOF infiltration enabling decisive follow-on action: quiet access, accurate intelligence, and a surgically executed assault.

Personal Reflections: A Living Lineage

My own journey with military kayaks began long before operational use, sparked by Second World War films such as The Cockleshell Heroes and Attack Force Z. Those stories planted an early appreciation for the concept long before I understood the discipline behind it.

When I arrived at 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), I sought assignment to an Underwater Operations Detachment commonly referred to as a dive team. Within three months, I had completed pre-scuba training and the Combat Diver Qualification Course (CDQC). My first deployment took me to Aqaba, Jordan, where kayak infiltration using Klepper folding kayaks was one of the methods we rehearsed.

When I arrived at 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), I sought assignment to an Underwater Operations Detachment commonly referred to as a dive team. Within three months, I had completed pre-scuba training and the Combat Diver Qualification Course (CDQC). My first deployment took me to Aqaba, Jordan, where kayak infiltration using Klepper folding kayaks was one of the methods we rehearsed.

Over the course of my career, we used kayaks for infiltration training, mothercraft launches, helocasting, and shore insertions. They were also used for long-distance paddling as physical training, team building, and on occasion as improvised fishing platforms. We rehearsed operational employment during a counter-narcotics mission that was ultimately cancelled due to circumstances outside our control.

Over the course of my career, we used kayaks for infiltration training, mothercraft launches, helocasting, and shore insertions. They were also used for long-distance paddling as physical training, team building, and on occasion as improvised fishing platforms. We rehearsed operational employment during a counter-narcotics mission that was ultimately cancelled due to circumstances outside our control.

As my responsibilities increased, culminating in my role as Command Diving Officer for 5th Special Forces Group, I came to appreciate the quiet value of having kayaks available in the dive locker and on team deployments. They represented a direct lineage to the OSS Maritime Unit and to allied formations such as the SBS and Z Special Force.

Preserving the Craft

Today, I am fortunate to own one of the original 5th Group Klepper kayaks, acquired when U.S. Special Forces transitioned to the American-made Long Haul variant. When I received it, the kayak consisted of mismatched parts in poor condition and was missing its hull skin entirely.

Over several months, I restored the frame to operational condition and sourced a new skin from Long Haul, which at the time held the U.S. repair contract for the original German Kleppers. Configured in a one-man expedition setup, the kayak is now used for physical training and personal stress relief a functional reminder of a demanding and enduring tradition.

Over several months, I restored the frame to operational condition and sourced a new skin from Long Haul, which at the time held the U.S. repair contract for the original German Kleppers. Configured in a one-man expedition setup, the kayak is now used for physical training and personal stress relief a functional reminder of a demanding and enduring tradition.

Conclusion

Kayaks remain in use by military and special operations units around the world. While rarely employed, they persist as a specialized capability within the maritime toolkit reserved for missions where stealth, endurance, and access outweigh speed or mass.

From Bordeaux to Singapore, the Zambezi to the Falklands, the military kayak has repeatedly proven that sophisticated effects do not always require complex machines. Sometimes, a paddle, patience, and exceptional fieldcraft are enough.

About the author: Travis Rolph is a retired Airborne Infantry and Special Forces veteran and founder of Mayflower Research & Consulting.

Hasler proposed a solution to a persistent operational problem: German shipping operating from the occupied port of Bordeaux, which had proven difficult for British Bomber Command to interdict. His plan envisioned a ten-man raiding force launched by submarine outside the mouth of the Gironde Estuary. From there, the team would paddle more than eighty miles during periods of limited visibility, emplace limpet mines on enemy shipping, and then evade by any means available, with the ultimate goal of returning to the United Kingdom.

Hasler proposed a solution to a persistent operational problem: German shipping operating from the occupied port of Bordeaux, which had proven difficult for British Bomber Command to interdict. His plan envisioned a ten-man raiding force launched by submarine outside the mouth of the Gironde Estuary. From there, the team would paddle more than eighty miles during periods of limited visibility, emplace limpet mines on enemy shipping, and then evade by any means available, with the ultimate goal of returning to the United Kingdom. Operation Frankton validated the concept of kayak-borne raiding and directly influenced the development of British maritime special operations doctrine. During this same period, multiple parallel kayak development efforts were underway in the United Kingdom, refining folding designs and techniques that would later inform the Special Boat Service (SBS) and allied units.

Operation Frankton validated the concept of kayak-borne raiding and directly influenced the development of British maritime special operations doctrine. During this same period, multiple parallel kayak development efforts were underway in the United Kingdom, refining folding designs and techniques that would later inform the Special Boat Service (SBS) and allied units. Following the Second World War, kayaks remained in service with special operations forces in the United Kingdom, Europe, Africa, Asia and the United States. One of the most compelling post-war examples comes from the Rhodesian Bush War.

Following the Second World War, kayaks remained in service with special operations forces in the United Kingdom, Europe, Africa, Asia and the United States. One of the most compelling post-war examples comes from the Rhodesian Bush War. Kayaks enabled silent night movement, an extremely low visual and acoustic signature, and continuous repositioning without reliance on fixed bases, vehicles, or aircraft. This operation remains one of the most extreme examples of fieldcraft, endurance, and waterborne stealth in modern special operations history. Conceptually, it aligns more closely with Second World War SBS and Combined Operations Pilotage Party (COPP) missions than with later helicopter-centric SOF models.

Kayaks enabled silent night movement, an extremely low visual and acoustic signature, and continuous repositioning without reliance on fixed bases, vehicles, or aircraft. This operation remains one of the most extreme examples of fieldcraft, endurance, and waterborne stealth in modern special operations history. Conceptually, it aligns more closely with Second World War SBS and Combined Operations Pilotage Party (COPP) missions than with later helicopter-centric SOF models. Launching at night from offshore, the team paddled in extreme South Atlantic weather to avoid detection. Once ashore, the kayaks were cached and the patrol transitioned to foot movement to conduct reconnaissance of aircraft disposition, defensive routines, and terrain.

Launching at night from offshore, the team paddled in extreme South Atlantic weather to avoid detection. Once ashore, the kayaks were cached and the patrol transitioned to foot movement to conduct reconnaissance of aircraft disposition, defensive routines, and terrain. When I arrived at 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), I sought assignment to an Underwater Operations Detachment commonly referred to as a dive team. Within three months, I had completed pre-scuba training and the Combat Diver Qualification Course (CDQC). My first deployment took me to Aqaba, Jordan, where kayak infiltration using Klepper folding kayaks was one of the methods we rehearsed.

When I arrived at 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), I sought assignment to an Underwater Operations Detachment commonly referred to as a dive team. Within three months, I had completed pre-scuba training and the Combat Diver Qualification Course (CDQC). My first deployment took me to Aqaba, Jordan, where kayak infiltration using Klepper folding kayaks was one of the methods we rehearsed. Over the course of my career, we used kayaks for infiltration training, mothercraft launches, helocasting, and shore insertions. They were also used for long-distance paddling as physical training, team building, and on occasion as improvised fishing platforms. We rehearsed operational employment during a counter-narcotics mission that was ultimately cancelled due to circumstances outside our control.

Over the course of my career, we used kayaks for infiltration training, mothercraft launches, helocasting, and shore insertions. They were also used for long-distance paddling as physical training, team building, and on occasion as improvised fishing platforms. We rehearsed operational employment during a counter-narcotics mission that was ultimately cancelled due to circumstances outside our control. Over several months, I restored the frame to operational condition and sourced a new skin from Long Haul, which at the time held the U.S. repair contract for the original German Kleppers. Configured in a one-man expedition setup, the kayak is now used for physical training and personal stress relief a functional reminder of a demanding and enduring tradition.

Over several months, I restored the frame to operational condition and sourced a new skin from Long Haul, which at the time held the U.S. repair contract for the original German Kleppers. Configured in a one-man expedition setup, the kayak is now used for physical training and personal stress relief a functional reminder of a demanding and enduring tradition.