From Feb. 2-6, 13 Soldiers from the 1st Armored Division, the Maneuver Center of Excellence (MCoE), and the Fires Center of Excellence, participated in a Soldier Touch Point (STP 0) at Fort Belvoir to engage with some of the Army’s latest technology under development—FALCONS.

FALCONS, which stands for Future Advanced Long-range Common Optical/Netted-fires Sensors, is set to replace the Long Range Advanced Scout Surveillance System (LRAS3). FALCONS integrates cutting-edge commercial technologies with advanced military sensors, including the Army’s third-generation Forward-Looking Infrared (3GEN FLIR) system.

Lt. Col. Ryan Welch, who leads Product Manager for Ground Sensors (PM GS) which manages the FALCONS program, said FALCONS will enhance Soldier performance where it matters most.

“FALCONS will improve the effectiveness of the Soldier on the battlefield by improving upon the legacy system, LRAS3/FS3, providing overmatch to our Scouts and Fire Supporters,” said Welch.

Designed for both mounted and dismounted operations, FALCONS pinpoints targets with precision to support a wide range of Army and joint munitions—whether precision-guided, near-precision, or conventional. Its networked architecture directly connects Scouts and Fire Supporters, accelerating coordination and shortening the kill chain.

One of the improvements with FALCONS includes the addition of artificial intelligence.

“FALCONS will integrate advancements in AI and machine learning into the most powerful IR [infrared] sensor on the battlefield to support Aided Target Detection and Recognition (AiTDR), which will reduce the cognitive load on operators,” Welch said.

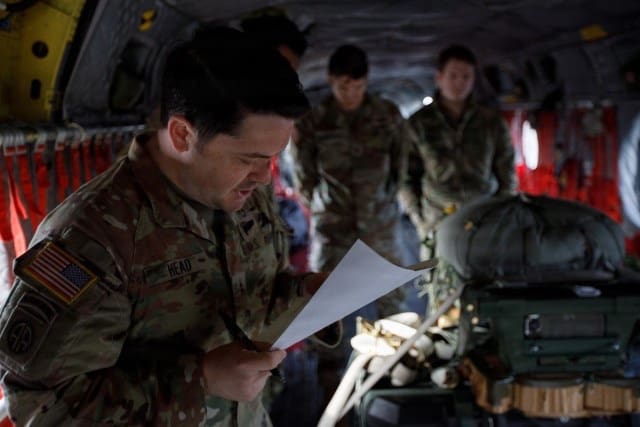

The STP 0, led by Research and Technology Integration’s (RTI) Sensor Evaluation and Digital Prototyping Division (SEDP), focused on eliciting feedback on initial vendor designs including ergonomics, button layout, and Graphical User Interfaces (GUI).

STPs are testing and feedback events where Soldiers provide insights on how systems or equipment undergoing development will be used in the field. The touch points provide helpful input to vendors, testers, researchers and acquisition experts on the capabilities Soldiers will need.

During SPT 0, Sgt. 1st Class Daniel Agriesti with the MCoE provided soldiers with a familiarization session on LRAS3 – an integral step needed to understand FALCONS prototypes during feedback sessions. Additionally, he participated in the Soldier touch point as a subject matter expert to provide feedback from a user perspective.

The feedback included how the hands of Soldiers interact with prototype components.

“How do they feel, how do they work, are they getting in the way, are they too big,” said Agriesti. “Especially with the new generation of Soldier[s] coming along they are a lot more gaming oriented based on what studies have told us.”

Engineering psychologists facilitated discussion and evaluation in the STP focus groups, meticulously documenting Soldier interactions with the prototypes and their verbal feedback.

Colleen Gerrity, one of several engineering psychologists who evaluated feedback at STP 0, said it is crucial her team is involved early on

“I feel like this Soldier touch point is unique because we are involved at the beginning of the process,” said Gerrity. “This is great because we are able to apply the academic rigor of research, design, and evaluation to ensure that the feedback is robust.

The feedback gathered during the event will accelerate the design process by enabling the early identification and mitigation of potential design flaws

STP 0 also underscored the importance of having fire support specialists and calvary scouts at future touch points, as their feedback, particularly on the GUI and operation of FALCONS, is essential to ensure vendor designs translate into something both intuitive and operationally effective

“STP 0 will inform future vendor designs as they prepare to transition into the initial design phase of the FALCONS prototyping,” Welch said.

He added that feedback from the touchpoint included Soldier preferences on handgrip design and button layout, the benefits of biocular versus binocular display, and the formatting of basic GUIs.

“The information gleaned will result in a more ergonomic design optimized for usability and employment in the diverse battlefield conditions that our Soldiers fight in across the globe,” Welch said.

Story by Michael Bortot, Capability Program Executive – Intelligence, Electronic Warfare & Sensors