BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA —

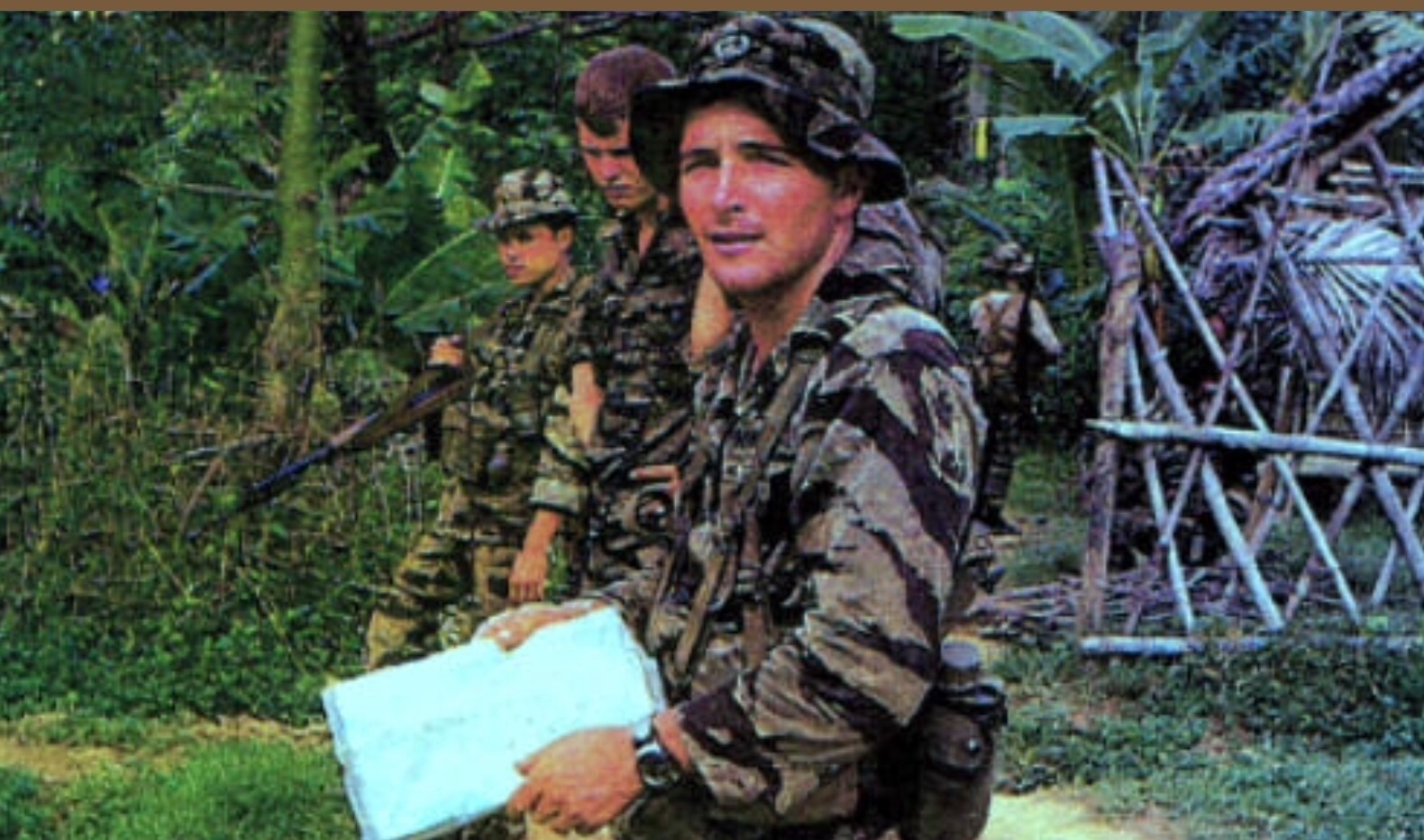

A Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) recovery team finished a joint field activity (JFA) in Bosnia and Herzegovina on May 31, 2024. They worked carefully with local officials and the U.S. Embassy to attempt to recover the remains of a U.S. service member missing since World War II. This team, composed of specialists from various fields, is united by a common mission: to bring our fallen heroes back home.

DPAA conducts extensive historical research on each case before excavation. Matt Cheser, a historian working at DPAA assigned to the Bosnian region, emphasized the importance of the work.

“There are still approximately 12 personnel missing from World War II in Bosnia,” Cheser stated. “It is our sacred obligation to bring them home.”

DPAA is committed to providing closure and peace to the families of the missing. To achieve this, each team deploys either a forensic anthropologist or forensic archaeologist as a scientific recovery expert (SRE) to study each case and lead excavations. This recovery team’s SRE, Dr. Laurel Freas, a DPAA forensic anthropologist, has been with the agency for 15 years. She explained how her extensive experience has prepared her for this mission.

“Every field mission I’ve done in the past has taught me important lessons that help me prepare for each new, upcoming mission,” Freas said. “For this mission, the most valuable past experiences relate to traveling to a new country, interacting with local officials we’ve never met before and who’ve never collaborated with DPAA before, and working with the team to bridge our differences in culture and language to convey the humanitarian nature of the agency’s mission.”

Freas highlighted the importance of earning trust and support from local officials.

“On this mission, we’ve been very fortunate to have excellent support from the local health inspector who has jurisdiction over the site where we were working,” said Freas. “I attribute that to the professionalism and dedication of the entire team.”

Garnering support from local officials is imperative to mission success but each mission and case are special and hold their own unique set of challenges.

“On most of my past missions, we were working in remote and isolated areas that are difficult to find, and even harder to get to,” said Freas. “On this mission, we’ve been working in and around a well-known local memorial monument, with all the concerns and sensitivities that go with that. It’s very important that we be conscious of our activities at all times, to make sure we’re always being respectful to the space we are working in.”

To face this challenge head-on and ensure collaboration success, DPAA works in partnership with multiple different organizations, commands, and programs. They acquire short term individual augmentees (STIA), such as linguists, who are valuable assets on every recovery team. Among the team members was U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. Nikola Bozic, a STIA linguist who previously assisted the DPAA in investigating this case back in 2022. Bozic’s unique language skills and cultural awareness proved invaluable for navigating the complex cultural landscape of Bosnia. His expertise, combined with the wonderful hospitality of the local officials, ensured the entire mission ran smoothly.

“Growing up in Bosnia has had a profound impact on how I approached various situations during our mission,” Bozic shared. “My deep understanding of the local culture and customs has allowed me to bridge the gap in understanding how the local community perceives our team’s efforts. This understanding has been crucial in navigating sensitive conversations and building trust, leading to more successful operations.”

To gain a better understanding of not only the language but the cultures and customs, linguist such as Bozic undergo extensive training in their backgrounds. Bozic received further training from the Air Force Cultural Language Center, specifically through the Language Enabled Airman Program (LEAP) and eMentor language training.

“This training has equipped me with practical skills for current and future DPAA missions or partnerships,” Bozic noted. “It has underscored the importance of cultural understanding in our missions.”

Prior to 2022, Bozic never thought that his training would contribute to such an operation.

“I was initially unaware of what DPAA does,” said Bozic. “However, after participating in DPAA missions, I can confidently say that these were the most fulfilling experiences of my military career. These missions allowed me to contribute to a noble cause and help bring back our missing service members. If given the opportunity to be part of DPAA’s missions, I highly recommend seizing the chance to do something that you will remember positively for the rest of your life.”

Bozic is one of the many linguists invited back by DPAA to increase mission success. He, like other STIAs, returns because he holds a deep belief in DPAA’s mission.

“It’s a noble cause dedicated to locating and bringing home the remains of missing service members.” Bozic said. “The tireless work of DPAA signifies its commitment to fulfilling the promise made to our service members that they will never be forgotten or left behind. This dedication offers reassurance to families that one day, their loved ones’ remains will be located and returned home.”

Freas echoed this feeling, stating, “I feel incredibly honored and privileged to be a part of DPAA and contribute to the Agency’s mission. I am proud of the work we do to provide answers to the families of the missing.”

As the DPAA team continues its work in Bosnia, they carry with them the hope and determination to bring closure to the families of those who served and sacrificed so much during World War II. Their efforts are a testament to the enduring promise that no service member will ever be forgotten.

See the full image gallery here: Bosnia and Herzegovina

By SSgt John Miller