“No one starts a war–or rather, no one in his sense ought to do so–without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by the war and how he intends to conduct it.”

Carl Von Clausewitz

“Don’t ever take a fence down until you know the reason it was put up.”

Gilbert. K. Chesterton

“In war, the moral is to the physical as ten to one.”

Napoléon Bonaparte

“War is not violence and killing, pure and simple; war is controlled violence, for a purpose. The purpose of war is to support your government’s decisions by force. The purpose is never to kill the enemy just to be killing him . . . but to make him do what you want him to do. Not killing . . . but controlled and purposeful violence.”

Robert A. Heinlein

“Basic truths cannot change and once a man of insight expresses one of them it is never necessary, no matter how much the world changes, to reformulate them. This is immutable; true everywhere, throughout all time, for all men and all nations.”

Robert A. Heinlein

Everyone who has read my articles knows that I am a big military history geek. Which explains why I spent a few days recently at Fort Benning, Georgia. Specifically, I was there to attend a History Symposium (March 10-11), the theme was “A 20-Year Retrospective on the Iraq War.” The event was sponsored by The National Infantry Museum and Columbus State University. Many of the people involved in setting it up were associated with USASOC and subordinate elements including SWCS. Several I had crossed paths with in Iraq. Generally, Military Historians dominated the first day’s discussion panels. All were retired career officers (most, but not all, were Iraq vets) who were now PhDs in academia. All had two or more books already published. The second day was a mix of other veterans of the war and published Anthropologists (someone who scientifically studies humans and their customs, beliefs, and relationships). Several were Iraqi Americans who had lived in Iraq before and during the war and as academics are still doing current research in Iraq. One was a veteran herself and Gold Star Spouse. She was deployed to Afghanistan when her husband was killed in Iraq. Her research was focused on surviving families of those service members killed and seriously injured in the war. Another was studying the long-term effects of Coalition Burn Pits and other toxic environmental impacts of the war on Iraqi civilians

As one would reasonably expect, the Anthropologists were generally “anti-war” and brought an impressive and convincing amount of data to support their position(s). A non-veteran might be surprised, but none of the veterans involved – with the full benefit of hindsight – had much positive to say about our county’s involvement in Iraq either. Various potentially provocative questions were presented by moderators for discussion and the panel(s) of experts provided their research, insights, and perspectives in response. For example, “Was the war a success or failure?” It was a spirited exchange and well worth my time. I was especially happy that in the audience were a good number of Army Officers and NCO students and cadre. I got to engage a lot of them, including several Marines going to school there. They were all sharp and surprisingly well informed on the history of Iraq (several had BAs in History). A couple had even been in Iraq, Syria, or Kuwait, recently in support of SOF operations

For those that might not have heard the term before, here is a definition of historiography for context. “The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians [of varying credibility] have studied that topic using particular sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches.” Legitimate historians use analytical skills like, “data analysis, research, critical thinking, communication, [and] problem-solving…” to get as accurate a picture of events as possible. Historians are part storytellers, but mostly operate like detectives. A historian sifts through the available evidence and develops a coherent theory of the crime (event) that can be supported by that evidence. Likewise, the historian also has to judge the reliability of the information provided by all the witnesses (sources). If new credible evidence is discovered then the original theory may be modified or discarded accordingly.

A historical event that is recent or ongoing, like the War in Iraq, has yet to have much truly analytic history written about it. Therefore, our understanding is still relatively shallow and dominated by less reliable and likely biased sources. Political or Military figures intent on justifying or rationalizing their decisions and actions, for example. In terms of storytelling, Historians work by first picking a reasonably objective “lens to look through.” Think of the device that optometrists use when they have you look at an eye chart and tell them which lens gives you the clearest view. In this case, a historian is both the patient and then the optometrist in the scenario. First getting the picture as clear as he can in his mind based on vetted sources and then through his or her writings helping an audience see that picture with the same clarity.

It was good to observe and participate in an event that involved professionals willing to go right up to uncomfortable facts about the war and look them in the eye without blinking or flinching away. It was also good for me to hear so many other perspectives on the subject. While I did not necessarily agree with every argument of every panelist at the Symposium, I thought they all made valid points worth considering. In that spirit, I am going to share some of my own observations about the war – for what they might be worth to the reader. No one need agree with me. In terms of my bona fides, I spent considerable time in the region and the countries bordering Iraq between 1991 and 2003 in 5th and then 3rd SFGs. I was no novice to local players, threats, and civil dynamics. I was there for the final planning and the run-up to the invasion phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). Altogether, I spent four years of my life in Iraq itself. And another three and a half in Afghanistan in between. Moreover, my jobs in SOF units required me to travel throughout the country; and, because I was “mid-management” I got to be close to the senior decision makers in every phase as well. I think, it is fair to say, that access probably gave me a broader perspective on the conflict than most.

Admittedly, given my intimate personal involvement, I may not always be an entirely detached or objective observer of those events myself. But, for personal and professional reasons, I try. I will start at the beginning of our invasion in March of 2003. The pre-invasion information (psychological operations) campaign was probably the most effective in history. We dropped leaflets and beamed radio and even television signals into Iraq intensely in the weeks leading up to the invasion. We told the Iraqi Army not to fight; the Coalition was only coming to remove the dictator Saddam; once that was accomplished then all Iraqis would be part of a better future. They believed us. For the most part, Iraqi soldiers and their officers abandoned their heavy weapons, shed their uniforms, and went home to await our instructions. In the weeks after the invasion Iraqi (Sunni) Generals and Colonels would visit US Forces and offer their services to re-muster their men at their former bases and immediately “go back to work” rebuilding their country – but they were always told to wait. We were going to renege on our promise.

Moreover, since we had already refused to assume “Occupying Force” status (as required by International Law) or established strict (Coalition imposed) martial law, the U.S. all but guaranteed that their repressed internal political and cultural demons would be unleashed against us and each other. I remember being in the parking lot of a multi-story shopping center in Baghdad in early April watching as Iraqis carried off merchandise as the Mall burned behind them. They waved and smiled at us as they passed by. We could have stopped it easily with a word. But we were under strict orders from Washington not to interfere. After all, they were “repressed people” just “letting off steam.” Bullshit! They were looters pure and simple. With our inaction, we squandered any claim to moral authority we might otherwise have had the chance to exercise. Instead of letting the Iraqi people know that there was a “new Sheriff in town” we sent the clear message that there was NO Sheriff in town, NO laws, and that anything goes.

In the case of Iraq, the Kurds and the Shia had been the classic ‘latent insurgents’ during the decades of Saddam’s Baathist Regime. Of course, Saddam took action to suppress those people by gassing the Kurds in the north and brutally putting down Shia uprisings in the south, particularly after Desert Storm. Our invasion in 2003 turned that repressive but stable arrangement on its head. Now the Sunni minority who had held uncontested power were the targets of immediate reprisal repression by the Shia – and the Sunni were very afraid. At the insistence of our Iraqi Shia “allies,” the US Government foolishly supported the implementation of the draconian “De-Baathification” laws which prevented any former Baathist from holding public office – permanently! That meant that every Sunni of even minor political stature was blacklisted. The Sunnis who could run for office were political lightweights and had no credibility even within the Sunni community. So, the Sunni largely boycotted the first round of national elections in protest. That was a mistake they recognized only too late. The Shia, therefore, consolidated their political control through the ballot box and at that point, the US, for all practical purposes, had done nothing more than replace a Sunni dictator with a de-facto Shia dictatorship.

One must understand something about the culture to recognize why this was so vindictive on the part of the Shia and so devastating to the Sunni pride. Wearing a uniform as a soldier or police officer gave those men a position of respect in their society. De-Baathification did not just take a job away from these men but rather served to effectively emasculate them. Publicly castrating them in the eyes of their families, clans, and tribes. It was an unforgivable insult to the Sunni and the Shia knew it – and the US allowed it. That is when the IEDs started appearing. At first, those devices were not particularly effective because they were mostly designed to send a message rather than inflict damage. But since no political accommodations were made – or even attempted – as the Summer turned into Fall, the situation continued to deteriorate. This was not an unintended consequence that was only recognized in hindsight. Many of us knew it was a major strategic mistake at the time and Military Leaders in country tried – desperately – to get Senior Leaders in Washington to reconsider. But, in their unbridled hubris, those in Washington were certain they knew best.

Therefore, it would be accurate to say that political inaction and cultural ignorance on the part of the US to restrain the blatant Shia moves to oppress the Sunni created the insurgency in Iraq. And we could have stopped it relatively easily and bloodlessly in that earlier stage. The key takeaway is that none of this required resolution through a counterinsurgency campaign – or a traditional military strategy of any kind. This quite probably could have and should have been negotiated politically and equitably but it would have required the US to ‘force’ the parties –especially the Shia – to some compromise. We deliberately chose not to explore that course of action and instead proceeded to conduct combat operations to eliminate the “handful of dead-enders” supposedly responsible. For all the fighting and destruction involved, the war has – to this day – still not resolved the underlying issues between those actors. It is worth noting for the historical record, the vast majority of the civilian casualties in the conflict were inflicted by the various native sects, paramilitaries, and insurgents on each other – not by Coalition Forces. Bottom line is, had we not helped set the fire in the first place we would never have been struggling to find the right way to put it out after it becomes a blazing inferno in the following many years.

That also illustrates one of the almost insurmountable challenges of COIN. We call it “counterinsurgency” and that name implies that the primary focus is on stopping the insurgent. But the insurgent is just the visible – and in many ways the smallest and least dangerous – manifestation of the massive subsurface “iceberg’ of societal issues that need to be addressed. The fundamental problem is one of Host Nation (HN) government legitimacy with their people. Your “partners” in the HN government are usually less than trustworthy or virtuous. Their own people know that. They are likely just the most ambitious and often ruthless rather than the best or brightest from that society. It is the harder, more complicated, and sometimes dirtier business to deal with the people who are supposed to be on “your side” in the conflict than it is to overcome the insurgents. That is also why it is HARD to convince the population in the affected area that their future is brighter with a government they do not trust and not with the insurgent.

One of the enduring misconceptions of the war is that FM3-24 Counterinsurgency (COIN), finally gave US Forces a “winning” doctrine. The popular mythos of that manual is that GEN Petraeus brought it down from a mountain on a stone tablet. It is supposed to be doctrinal lightning in a bottle, holds all the answers, and was not to be questioned. I am exaggerating only slightly. Unfortunately, FM3-24 relies a great deal on the US experience in Vietnam. The fact is that most of our COIN initiatives in Vietnam failed miserably. Obviously, we should want to avoid the well-studied pitfalls of that not-so-distant historical debacle. Yet, instead, we have made a point of reapplying the exact same flawed methodologies in Iraq and Afghanistan these last two decades. It does little good to study history if you do not learn the right lessons. Remember: in Vietnam, we won all the battles, and we won all the gunfights in Iraq and Afghanistan. So what? As a North Vietnamese General famously said “That is true but it is irrelevant.”

That is why the COIN fighting forces can have high morale and unbroken will and achieve those tactical successes…and still not be winning at the strategic level. No matter how hard or fast we “whack the moles,” if the insurgent can absorb those losses and maintain their collective will it is almost impossible to eliminate them by direct combat. That is where it gets complicated. In order to defeat the insurgents, you have to “attack” and resolve or at least mitigate the political, economic, or social issues that created the insurgent in the first place. He is the weed; you can cut him down endlessly with no lasting effect. It is vital to go after the roots. An unbroken string of tactical victories not only does not guarantee success, but it may also actually contribute in a counterintuitive way to ultimate failure. I would argue that FM3-24 was not the doctrinal miracle cure it was sold as but rather at best a placebo, at worse snake oil. Real innovation is needed in how we as a nation (and Allies) approach this kind of conflict. If we do it, we have to accept that it is harder and more complicated than we would like; and to be successful requires a longer –rather than shorter – commitment on our part.

I would suggest something on par with US involvement in rebuilding and shaping post-WWII Germany and Japan. Granted, in those cases, there was not an inherently unstable trifurcated society like Iraq. But, those are important valid historical examples where US Military guided nation-building or re-building worked well. I have often argued that we had no issue with potentially violent insurgencies in occupied Germany or Japan after WWII precisely because we established military “Law and Order” immediately, committed ourselves to remain in place as long as necessary to achieve our goals, and task organized ourselves as a “Constabulary” to maintain the civil peace. I had an Uncle, who served as a paratrooper in the Pacific in WWII. He airlanded in Japan a few days after the surrender. Surprisingly, he and his compatriots were not met with hostility. In fact, after a few weeks, off-duty American soldiers would walk the local streets unarmed. The situation was much the same in Germany. That hard won peace allowed new – truly functional and legitimate – governments to be established in relatively short order – without additional violence. I am convinced that we had the real opportunity in those early days in Iraq to do just that. But we squandered the chance and we and the Iraqi people paid a terrible and unnecessary price for our lack of imagination and vision.

I was in country before, during, and after the so-called “Surge Strategy” period. The initiative that became known as the ‘Sunni Awakening’ began in earnest in early 2006 before FM 3-24 was even published. So, the new doctrine was not a factor. Nor had any of the promised US “Surge Forces” arrived in country at that time. The Sunni Awakening did not ‘stabilize’ Iraq either. The Sunni tribes cut a deal directly with U.S. Forces rather than actually reconciling with the Shia dominated government in Baghdad. The Shia government was never on board and, in fact, resented this ‘sidebar’ bilateral arrangement. The Shia were also opposed to the ‘accommodation’ for semi-autonomy we had pushed with the Kurds in the north. Perhaps if U.S. Forces had stayed, we might have mitigated the collapse of the Iraqi Army in front of the ISIL advances in 2014. But the Shia began to reassert themselves – refused a Status of Forces Agreement – and moved to re-disenfranchise the Sunni and re-marginalize the Kurds even before U.S. Forces withdrew at the end of 2011. Our continued presence was not stopping or even slowing that process. Nor is it likely it would have if we had stayed even longer.

I left Iraq for the last time in March, 2011. It was already crystal clear that the Iraqi Government intended to undo much of what we had done toward the end to bring the factions marginally closer together. And we knew that process would begin in earnest immediately after we got out of their way. The Sunni Awakening itself was very helpful in reducing the immediate sectarian violence – but it solved nothing. It served only to defer the pressing need to resolve the intractable internal political issues of the Iraqi government. In fact, because the reduction in violence was so encouraging, the American people were led to believe that the war was won. And that public misperception precipitated the withdrawal plan first negotiated toward the end of the Bush Administration. In short, the alleged ‘success’ of the surge strategy gave us the adequate military pretext and the convenient political excuse to declare victory and leave.

We consistently made the fatal mistake of confusing enthusiasm with capability. The War in Iraq is not something I can be completely dispassionate about. I lost people there. My generation will carry scars from the war for the rest of our lives – as Vietnam veterans did before us. I have said this before, but I will repeat it now. We paid in blood to buy the politicians of all the countries involved, especially the Iraqi and American governments, precious time to resolve those underlying challenges we talked about in the Symposium and I elaborated on in my comments. I am certainly not satisfied with the clearly suboptimum outcome we ended up with, but Iraq is stable for the moment. The professionals I served with – including every Service of the US Military, Inter-Agency Partners, Allies, and Iraqi Security Forces – did their duty. I do take satisfaction in the fact that we did everything that was asked of us – and then some. We kept the faith! I can live with that.

De Oppresso Liber!

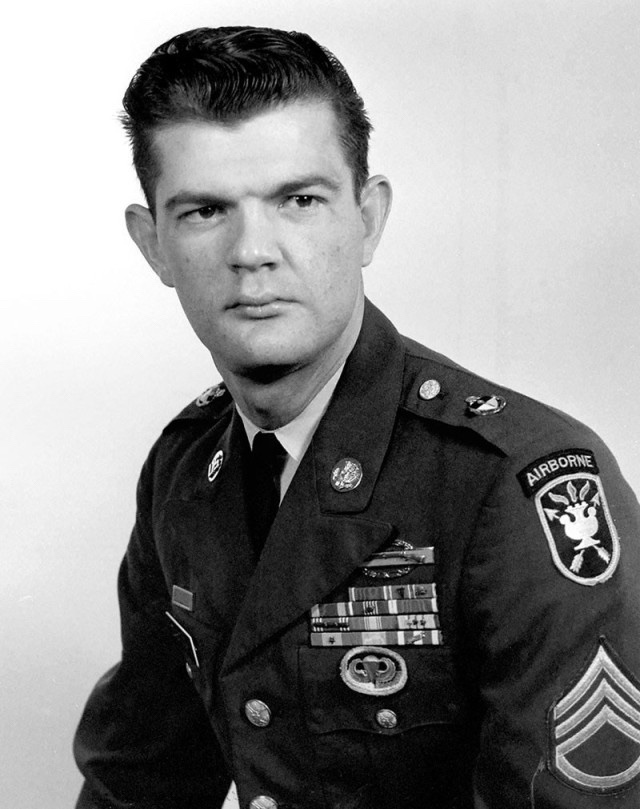

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.