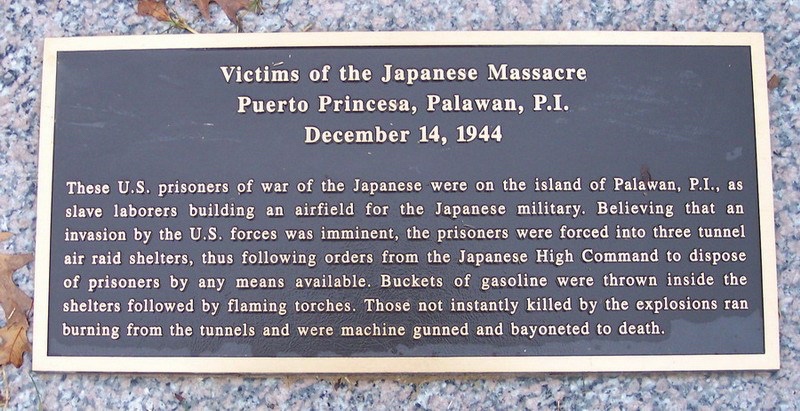

The Palawan massacre occurred on 14 December 1944, during World War II, near the city of Puerto Princesa in the Philippine province of Palawan. The Japanese Imperial Army massacred 139 of 150 American POWs. The Palawan compound was named Camp 10-A by the japanese, and the prisoners were quartered in several unused Filipino constabulary buildings. Food was almost nonexistent; the prisoners received a daily meal of wormy Cambodian rice and a canteen cup of soup made from camote vines boiled in water (camotes are a Philippine variant of sweet potatoes). Prisoners who could not work had their rations cut by 30%.

The Japanese unit in charge of the prisoners and the airfield at Palawan was the 131st Airfield Battalion, it was command of Captain Nagayoshi Kojima, whom the Americans called the Weasel. Lieutenant Sho Yoshiwara commanded the garrison company, and Lieutenant Ryoji Ozawa was in charge of supply. Ozawa’s unit had arrived from Formosa in 1942 and had previously been in Manchuria. There was also a Military police and intelligence unit, called the kempeitai at Palawan, they were feared by anyone who fell into their hands because of their brutal tactics.

In September 1944, 159 of the American POWs at Palawan were returned to Manila. The Japanese estimated that the remaining 150 men could complete the arduous labor on the airfield, hauling and crushing coral gravel by hand and pouring concrete seven days a week. The men also repaired trucks and performed a variety of maintenance tasks in addition to logging and other heavy labor

An attack by a single American Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber on 19 October 1944, sank two enemy ships and damaged several planes at Palawan. More Liberators returned on 28 October and destroyed 60 enemy aircraft on the ground. While American morale in the camp soared, the treatment of the prisoners by the Japanese grew worse, and their rations were cut. After initially refusing the prisoners’ request, the Japanese reluctantly allowed the Americans to paint American Prisoner of War Camp on the roof of their barracks. This gave the prisoners some measure of protection from American air attacks. The Japanese then stowed their supplies under the POW barracks.

On 14 December, Japanese aircraft reported the presence of an American convoy, which was headed for Mindoro, but which the Japanese thought was destined for Palawan. All prisoner work details were recalled to the camp at noon. Two American Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter aircraft were sighted, and the POWs were ordered into the air-raid shelters. After a short time, the prisoners re-emerged from their shelters, but Japanese 1st Lt. Yoshikazu Sato, whom the prisoners called the Buzzard, ordered them to stay in the area. A second alarm at 2 p.m. sent the prisoners back into the shelters, where they remained, closely guarded.

Suddenly, in a deliberate and planned move, 50 to 60 Japanese soldiers under Sato’s leadership doused the wooden shelters with buckets of gasoline and set them afire with flaming torches, followed by hand grenades. The screams of the trapped and doomed prisoners mingled with the cheers of the Japanese soldiers and the laughter of their officer, Sato. As men engulfed in flames broke out of their fiery deathtraps, the Japanese guards machine-gunned, bayoneted and clubbed them to death. Most of the Americans never made it out of the trenches and the compound before they were barbarously murdered. Still, several closed with their tormentors in hand-to-hand combat and succeeded in killing a few of the Japanese attackers.

Marine survivor Corporal Rufus Smith described escaping from his shelter as coming up a ladder into Hell. The four American officers in the camp, Lt. Cmdr. Henry Carlisle Knight (U.S. Navy Dental Corps), Captain Fred Brunie, Lieutenant Carl Mango (U.S. Army Medical Corps) and Warrant Officer Glen C. Turner, had their dugout, which the Japanese also doused with gasoline and torched. Mango, his clothes on fire, ran toward the Japanese and pleaded with them to use some sense but was machine-gunned to death.

About 30 to 40 Americans escaped from the massacre area, either through the double-woven, barbed-wire fence or under it, where some secret escape routes had been concealed for use in an emergency. They fell and/ or jumped down the cliff above the beach area, seeking hiding places among the rocks and foliage. Marine Sergeant Douglas Bogue recalled: Maybe 30 or 40 were successful in getting through the fence down to the water’s edge. Of these, several attempted to swim across Puerto Princesa’s bay immediately but were shot in the water. I took refuge in a small crack among the rocks, where I remained, all the time hearing the butchery going on above. They even resorted to using dynamite in forcing some of the men from their shelters. I knew [that] as soon as it was over up above, they would be down probing among the rocks, spotting us and shooting us. The stench of burning flesh was strong. Shortly after this, they were moving in groups among the rocks dragging the Americans out and murdering them as they found them. By the grace of God, I was overlooked.

Eugene Nielsen of the 59th Coast Artillery observed, from his hiding place on the beach, a group of Americans trapped at the base of the cliff. He saw them run-up to the Japs and ask to be shot in the head. The Japs would laugh and shoot or bayonet them in the stomach. When the men cried out for another bullet to end their misery, the Japanese continued to make merry of it all and left them there to suffer. Twelve men were killed in this fashion. Nielson hid for three hours. As the Japanese were kicking American corpses into a hole, Nielson’s partially hidden body was uncovered by an enemy soldier, who yelled to his companions that he had found another dead American. Just then, the Japanese soldiers heard the dinner call and abandoned their murderous pursuit in favor of hot food. Later, as enemy soldiers began to close in on his hiding place, Nielson dived into the bay and swam underwater for some distance. When he surfaced, approximately 20 Japanese were shooting at him. He was hit in the leg, and bullets grazed his head and ribs. Even though he was pushed out to sea by the current, Nielson finally managed to reach the southern shore of the bay.

He was one of 11 prisoners of war who escaped the December 1944 massacre on Palawan Island in the Phillippines, where around 140 soldiers died when the Japanese put them into trenches, dumped gasoline on them and set them on fire. He was later a key witness in the War Crime Trials of 1945.

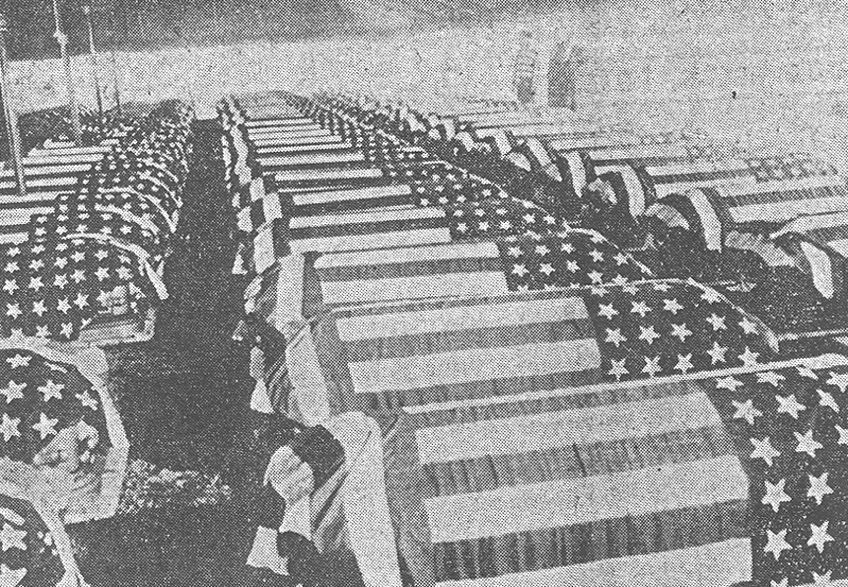

This biography tells the story of Glenn (“Mac”) McDole, one of eleven young men who escaped and the last man out of Palawan Prison Camp 10A. Beginning on 8 December 1941, at the U.S. Navy Yard barracks at Cavite, the story of this young Iowa Marine continues through the fighting on Corregidor, the capture and imprisonment by the Japanese Imperial Army in May 1942, Mac’s entry into the Palawan prison camp in the Philippines on 12 August 1942, the terrible conditions he and his comrades endured in the camps, and the terrible day when 139 young soldiers were slaughtered. The work details the escapes of the few survivors as they dug into refuse piles, hid in coral caves, and slogged through swamp and jungle to get to supportive Filipinos. It also contains an account and verdicts of the war crimes trials of the Japanese guards, follow-ups on the various places and people referred to in the text, with descriptions of their present situations, and a roster of the names and hometowns of the victims of the Palawan massacre.

www.humanitiestexas.org/news/articles/interview-rufus-w-smith-world-war-ii-pow