If you follow history, there is a lot said about how different battles were, this group took this hill, or this guy did this. But a lot needs to be said about what goes on behind the scenes. While the United States Army Signals Intelligence Section (SIS) and the Navy Communication Special Unit worked in tandem to monitor, intercept, decode, and translate Japanese messages during World War II, Operation Magic was the cryptonym used to refer to the United States’ efforts to break Japanese military and diplomatic codes. The Office of Strategic Services received the intelligence information acquired from the transmissions and forwarded it to military headquarters (OSS). It is widely acknowledged that the capacity to interpret and understand Japanese communications was a crucial component of the Allied triumph in the Pacific.

Early in 1939, the United States began its efforts to decipher Japanese diplomatic and military communications, even before the outbreak of World War II in Europe. In 1923, a United States Navy intelligence officer got a contraband copy of the Japanese Imperial Navy Secret Operating Code from World War I. Afterward, after all of the additive code keys had been discovered, the codebook was photographed and sent to the Research Desk, arranged in red folders by the cryptologists. The simple additive code was given the name “Red” in honor of the directories in which it was initially kept.

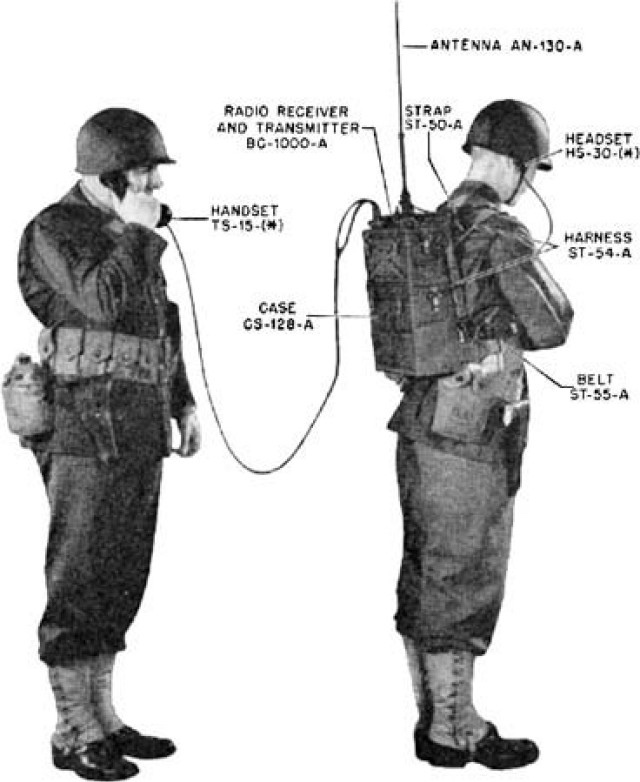

In 1930, the Japanese updated the Red code with Blue, a more sophisticated code for high-level communications. However, because the new code was too similar to its predecessor, cryptologists in the United States could fully decrypt the new code in less than two years after its introduction. At the onset of World War II, the Japanese were still using both Red and Blue color codes for various communications purposes. Listening stations were set up all across the Pacific by the United States military intelligence to monitor ship-to-ship, command-to-fleet, and land-based communications between ships.

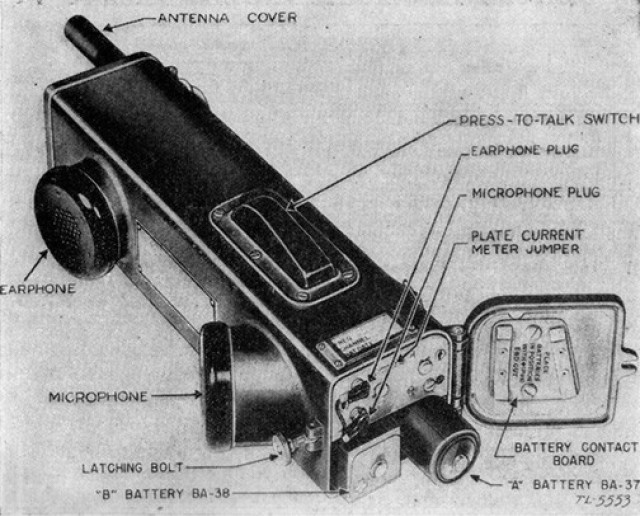

The Japanese acquired encryption and security assistance from Nazi Germany after World War II erupted across Europe. Since 1935, the Germans have known that U.S. intelligence is monitoring and decoding Japanese communications, but they have not instantly informed the Japanese of this fact. Later, Germany delivered a modified version of its iconic Enigma encryption machine to Japan to assist the country in securing its communications. As a result of this, American intelligence was unable to understand Japanese intercepts. The tedious job of United States cryptologists was restarted.

Cryptanalysts in the United States gave the new code the moniker Purple. Purple, used to decrypt numerous variants of the original Enigma code, was the most severe obstacle to American and British intelligence throughout World War II.

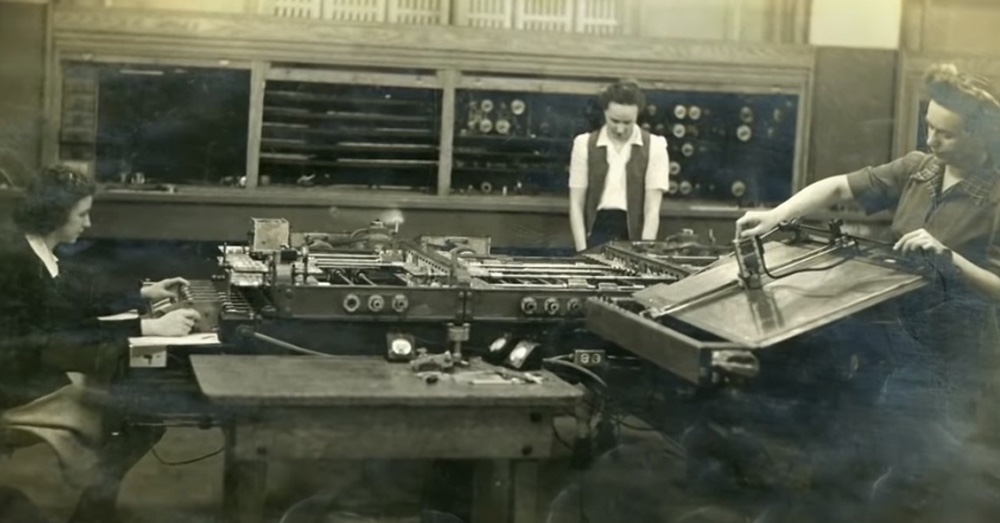

After receiving information from Polish and Swedish cryptologists, the British military intelligence cryptanalysis unit at Bletchley Park became the first in the world to decrypt the German Enigma code in 1942. They then created advanced decoding bombes and the world’s first programmable computer to aid in the deciphering of the complex Enigma cipher. By 1943, British intelligence could use information obtained through translated Enigma intercepts received in near real-time.

For years, cryptologists in the United States sought to break the Purple code by hand. However, the format of Japanese signals, always opening with the exact introductory phrase, enabled code breakers to establish the sequencing of the multi-rotor Japanese cipher machine. By 1941, code breakers in the United States had made significant headway in cracking the Purple code, and they had gained the capacity to decipher multiple lines of intercepted messages. The procedure remained sluggish, and the information obtained from Purple was frequently outdated when translated into another language.

United States military intelligence became aware of British victories against Germany’s Enigma machine and requested that their allies share code-breaking information. Top Bletchley Park cryptographers and engineers were dispatched to the United States to assist in training code breakers and constructing decoding bombes. But they were highly protective of and didn’t want anyone to know about their Enigma code-breaking activities (codenamed Operation Ultra), which involved Colossus, the Bletchley Park decoding computer, and which they were involved.

United States intelligence made significant headway against Purple in a short period, thanks to the assistance of the British. A copy of the Japanese Purple machine, created in 1939 by American cryptologist William Friedman, was used to adapt a German Enigma bombe to decode Japanese Purple, which was then used to decode the Japanese Purple machine. Even though each message’s settings had to be determined by hand, United States intelligence improved its ability to read Japanese code with greater ease and timelier by 1942, six months after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into World War II.

With the help of their vast network of listening stations in the Pacific, the United States intelligence services could intercept and decode various other sorts of communications. In conjunction with JN-25 intercepts, the Diplomatic Purple transmissions, another broken Japanese Navy code, provided critical information to the United States military command about Japanese fortifications at Midway. The intercepts from Operation Magic provided valuable input during the ensuing Battle of Midway, which helped to turn the tide of the Pacific War in the allied forces’ favor and ultimately win the war. Approximately a year later, Purple intercepts provided the United States with intelligence about a diplomatic aircraft on which Japanese General Yamamoto, the mastermind behind the Pearl Harbor assault, was scheduled to travel. The Japanese aircraft were shot down by American planes.

Operation Magic was a vital source of intelligence information in both the Pacific and European theaters of conflict during World War II. Diplomatic messages between Berlin and Tokyo, encrypted with the Enigma and Purple codes, provided British and United States intelligence with information about German defenses in France during the Second World War. This information aided leaders in their preparations for the D-Day invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

The Japanese government remained uninformed despite the fact that the United States had broken the Purple code. According to the United States government, Japanese Imperial forces continued to employ the principles decrypted by Operation Magic throughout the war and in the weeks following the Japanese surrender in 1945.