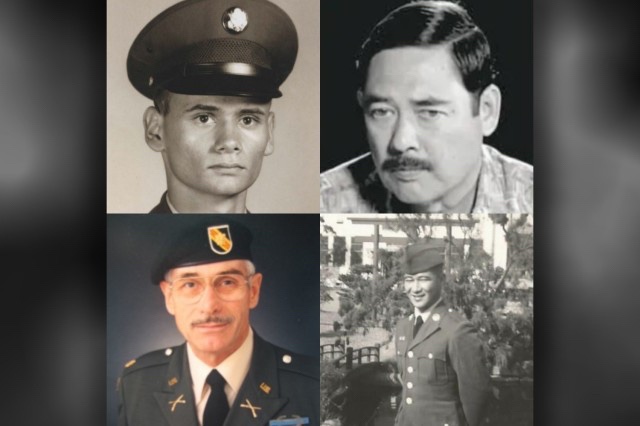

WASHINGTON — Four Vietnam War Soldiers who repeatedly put themselves in harm’s way to defend injured comrades will be awarded the Medal of Honor during a ceremony at the White House on July 5, 2022, according to the White House.

Two of the recipients, Spc. 5 Dwight Birdwell and Maj. John Duffy, rebuffed multiple enemy attacks while leading fellow Soldiers and allies to safety. Both Birdwell and Duffy sustained wounds but continued to engage the enemy.

Spc. 5 Dennis Fujii, a combat medic, refused rescue attempts after facing a wave of enemy fire, remaining on the ground to treat the wounded.

Staff Sgt. Edward Kaneshiro, an infantryman, who will receive the medal posthumously, helped rescue trapped survivors of two U.S. squads who had been ambushed by enemy forces in a Kim Son Valley village. Kaneshiro later died while continuing his service in Vietnam.

KANESHIRO

In a village near Phu Huu 2, a large North Vietnamese contingent ambushed two squads from Kaneshiro’s platoon on Dec. 1, 1966. Kaneshiro, a squad leader with Troop C, First Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, was scouting land east of the village at the time of the attack.

Kaneshiro directed his squad toward the sound of the fire, where enemy forces had killed his platoon leader and several other Soldiers, and had his two sister squads pinned down. Kaneshiro swiftly read the situation and realized that the fire from a machine-gun bunker and large concealed trench had to be stopped if anyone were to survive. Kaneshiro deployed his men to cover, then crawled forward, alone, to attack the enemy force.

While flattened to the ground he was somehow able to throw a grenade through the aperture of the bunker, eliminating it as a threat. Next he leapt into the trench and single-handedly worked his way down its entire 35-meter length, destroying one group of enemies with his rifle and two more enemy groups with grenades.

Kaneshiro’s assault allowed the pinned-down squads to survive and prepare their casualties for evacuation. His actions enabled the orderly extrication and reorganization of the platoon.

Kaneshiro would continue his tour in Vietnam until his passing on March 6, 1967, when he died by enemy gunshot wound at the age of 38.

BIRDWELL

On Jan. 31, 1968, a large North Vietnamese element attacked Birdwell’s unit — Troop C, 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry, 25th Infantry Division — at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, just outside of Saigon on the first day of what would later become known as the Tet Offensive. Birdwell’s unit bore the brunt of the initial attack, which destroyed many of the unit’s vehicles and incapacitating Birdwell’s tank commander. Under heavy small-arms fire, Birdwell moved his commander to a place of safety and slid into the commander’s hatch.

Armed with the tank’s machine gun and cannon and his M16 rifle, Birdwell fired upon the North Vietnamese. When he exhausted all of his ammunition, Birdwell dismounted and maneuvered to his squadron commander’s helicopter, which had been downed by enemy fire, and retrieved two machine guns and ammunition, with which he and a comrade suppressed the enemy. His machine gun was struck by enemy rounds and exploded, injuring his face and torso.

Birdwell refused evacuation and moved amongst the disabled vehicles and defensive positions, collecting ammunition to distribute to the remaining defenders. While under harassing fire, Birdwell led a small group of defenders past the enemy force and engaged the enemy with hand grenades, disrupting their assault until reinforcements arrived. Birdwell continued to treat wounded until he was ordered to seek medical attention.

FUJII

As a crew chief serving with the 237th Medical Detachment, 61st Medical Battalion, 67th Medical Group, Fujii engaged in rescue operations that transported injured South Vietnamese personnel over Laos and the Republic of Vietnam on Feb. 18, 1971. During a second approach to a hot landing zone, the enemy concentrated a barrage of flak at Fujii’s helicopter, causing it to crash in the conflict area, injuring Fujii.

A second helicopter was able to land and load all of his fellow downed airmen. However, Fujii was not able to board because the enemy directed fire on him. Rather than endanger the lives aboard the second helicopter, Fujii waved it off to leave the combat area. Subsequent attempts to rescue him were aborted due to the violent anti-aircraft fire. Fujii secured a radio and informed the aviators in the area that the landing zone was too hot for further evacuation attempts. Fujii remained as the lone American on the ground, treating the injuries of South Vietnam troops throughout the night and the next day.

On the night of Feb. 19, their perimeter came under assault by an enemy regiment and artillery fire. He called U.S. gunships to aid their small force in the battle. For more than 17 hours, Fujii repeatedly exposed himself to hostile fire as he left his entrenchment to observe enemy troop positions and direct air strikes against them. At times the group’s survival was so tentative that Fujii was forced to interrupt radio transmittal in order to place suppressive rifle fire on the enemy while at close quarters.

Though wounded and severely fatigued, Fujii’s actions led to the successful defense of the South Vietnamese troops and their encampment.

Then, after a helicopter was finally able to airlift him from the battle, enemy rounds pierced its hull forcing it to crash-land at a friendly camp, where Fujii would spend another two days before being evacuated.

DUFFY

During April 14-15, 1972, Duffy, part of Team 162 Military Assistance Command-Vietnam, was senior advisor to the South Vietnamese 11th Airborne Battalion at Fire Support Base Charlie in South Vietnam. In the days before, the enemy had destroyed the battalion command post, and the 11th’s commander had been killed; Duffy himself was twice wounded.

But instead of being evacuated, Duffy led a two-day defense of the surrounded FSB against a battalion-sized enemy force.

During the attack Duffy moved himself close to the enemy, to an exposed position, in order to call in air strikes. Despite being injured again after being struck by fragments from a recoilless rifle round, Duffy stayed and directed U.S. helicopter gunships onto enemy anti-aircraft and artillery positions.

After a severe, 300-artillery-round attack on the base, Duffy personally ensured the wounded troops were moved to safer positions and distributed ammunition to the remaining defenders.

That afternoon, the enemy began a ground assault on the firebase from all sides. Duffy moved from position to position to spot targets for artillery and to adjust fires. The next morning, after the 11th survived an ambush, Duffy led wounded to an evacuation area while in continual pursuit by the enemy.

By Joe Lacdan, Army News Service