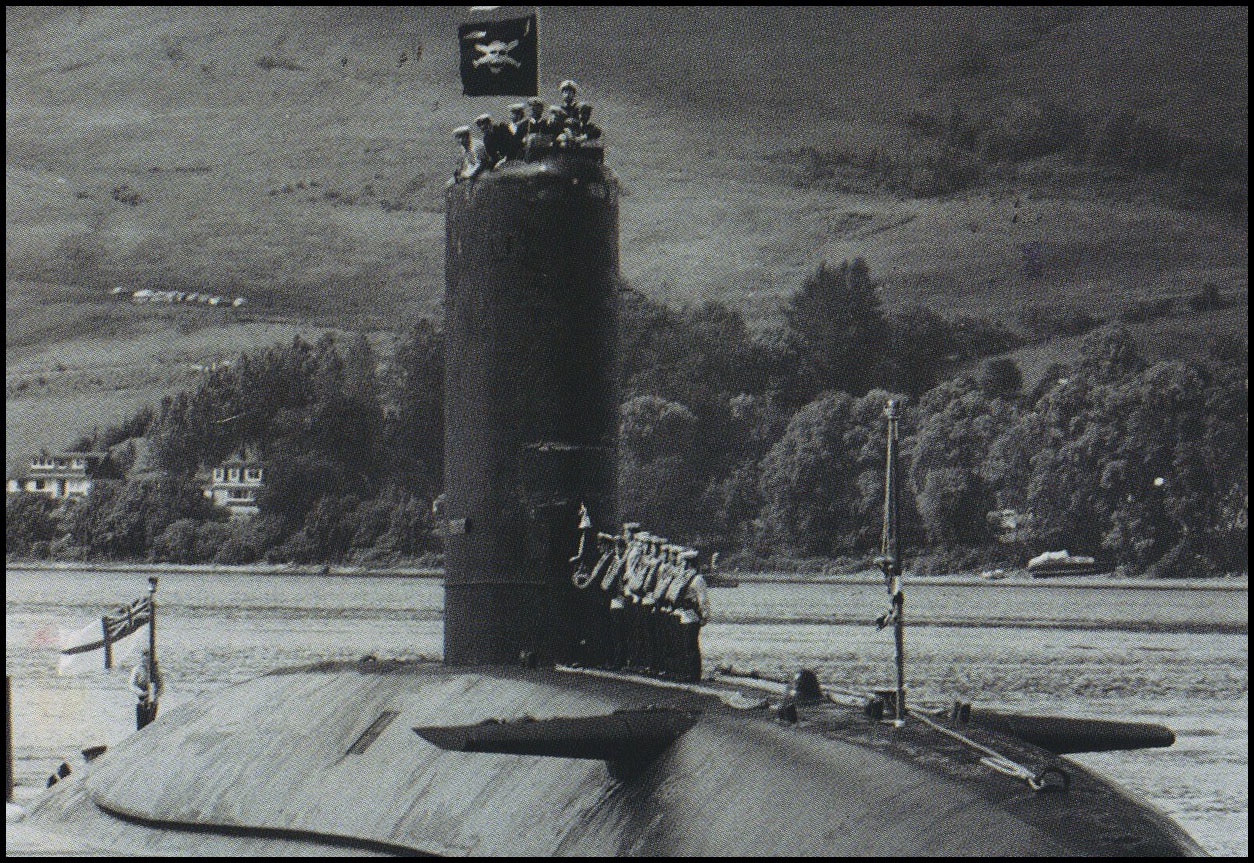

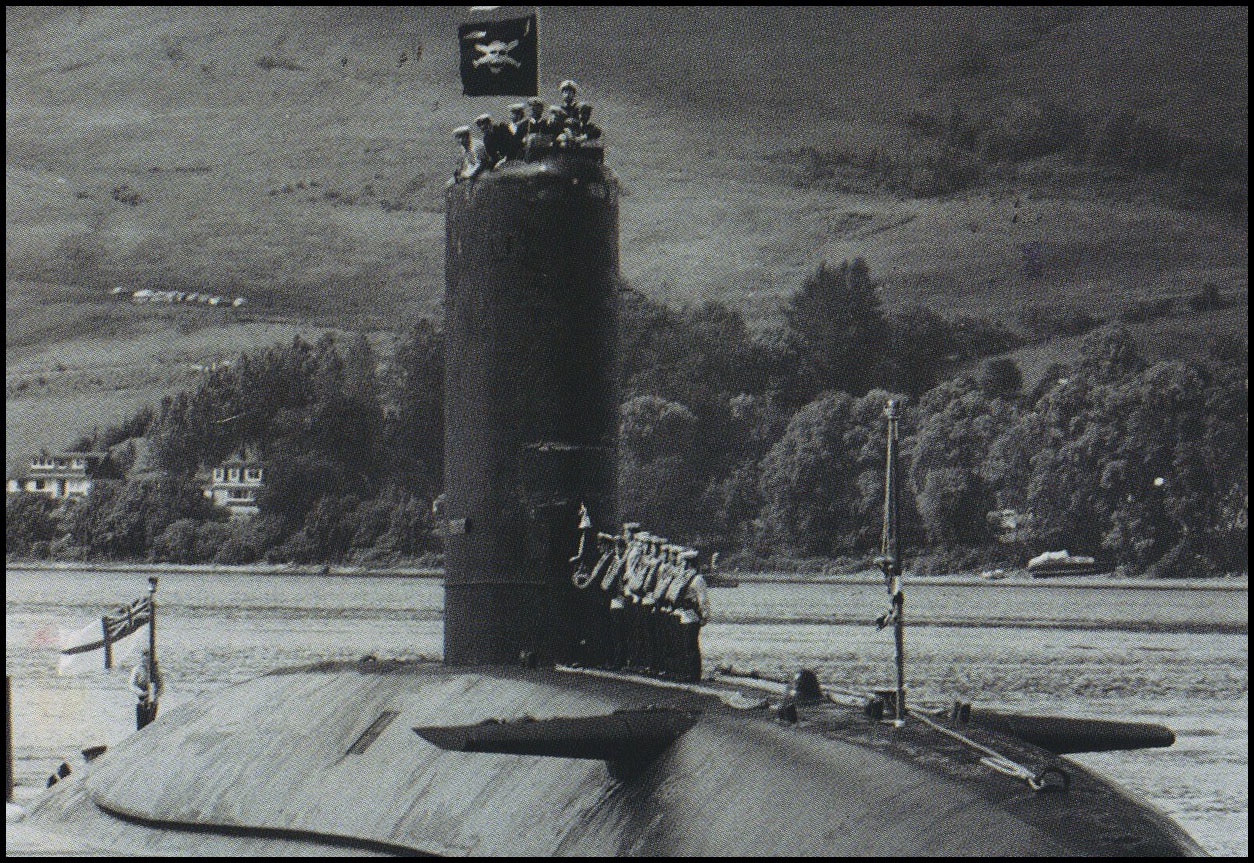

HMS Conqueror was a nuclear-powered attack submarine and one of the Royal Navy’s most powerful ships in the 1980s. As part of the Falkland Islands Re-taken operation, she sank the Argentine Navy light cruiser ARA General Belgrano. It was only the second submarine torpedo sinking since WWII.

After returning to the U.K., the Conqueror would be tasked to steal a secret sonar array from a Soviet Navy ship. It was code-named Operation Barmaid, and the nuclear-powered sub would be fitted with a special pair of remote-controlled heavy steel cutting blades and television cameras, so they could sneak up on a Russian spy trawler towing a sonar array and just cut it off and then float away.

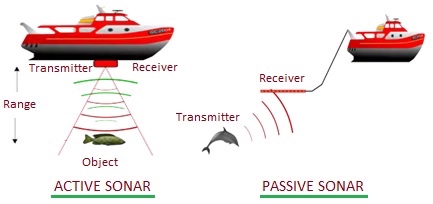

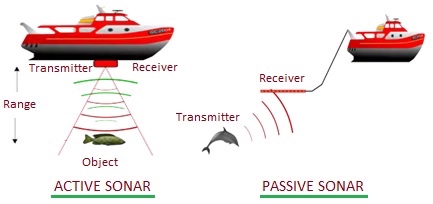

During the Cold war, the U.S. and the U.K. had a significant advantage over the Soviets regarding submarine warfare. We had two different types of SONAR, Active and passive. Active sonar sends out pings, which travel through the ocean before returning to the ship that sent them. Active sonar pings and machinery noise are detected by passive sonar. Passive sonar is challenging to use effectively due to the ship’s noise, particularly the propeller noise. A mile or more behind a boat, passive sonars are used. The easiest way to put it active SONAR is to put pings out and wait to hear if it bounces off anything. Passive is when you drag a cable behind you that has a bunch of microphones(hydrophones) on it, and you listen.

They noticed that Russian submarines were becoming quieter and faster in the late 1970s and feared that they were not making enough progress in naval technology. Because the array itself made no noise, learning about it required sitting in front of one and dismantling it. So, the U.S. and U.K. decided to steal one to see if the one the Soviets had was anything like the one they used. The plan was to sneak up behind the towed ship, a Polish intelligence vessel, and use the pincers to free the array.

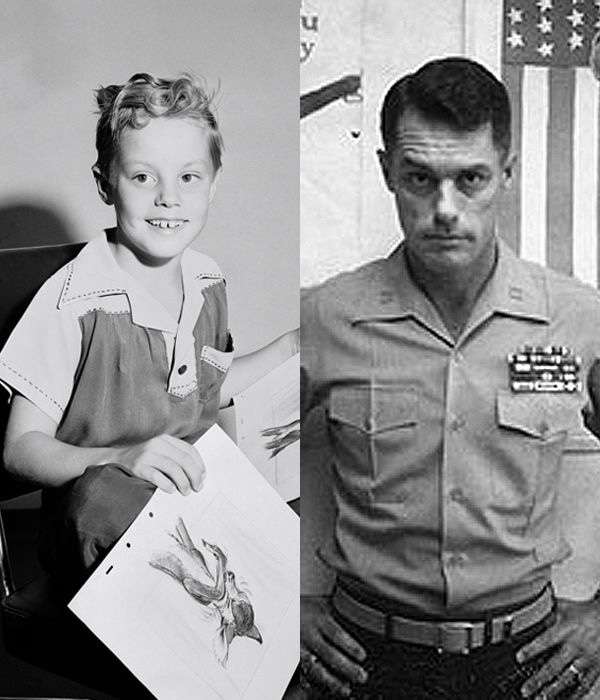

It was a complicated plan. First, the Conqueror, led by Captain Christopher Wreford-Brown, had to intercept a Soviet intelligence ship in international waters. Detected would have meant immediate, lethal retribution to cut through a three-inch-thick steel cable.

Second, the sub had to operate while both ships were moving. Third, the submarine had to avoid the passive SONAR array and remove it from the trawler without being seen.

The submarine was ordered to steal a two-mile string of hydrophones from a Polish-flagged spy trawler near Russian waters. Known as AGIs (Auxiliary General Intelligence), these trawlers were common during the Cold War, often disguised as fishing trawlers. But most had no fishing nets.

They used American-made pincers to make it look like it had snagged and been torn off accidentally; it would make a lot of small compression-type cuts and not just one straight throw cut again so it would look like it was ripped off and not cut. The Conqueror had to enter the ship’s blind spot and cut the cable just yards from the vessel and its propeller.

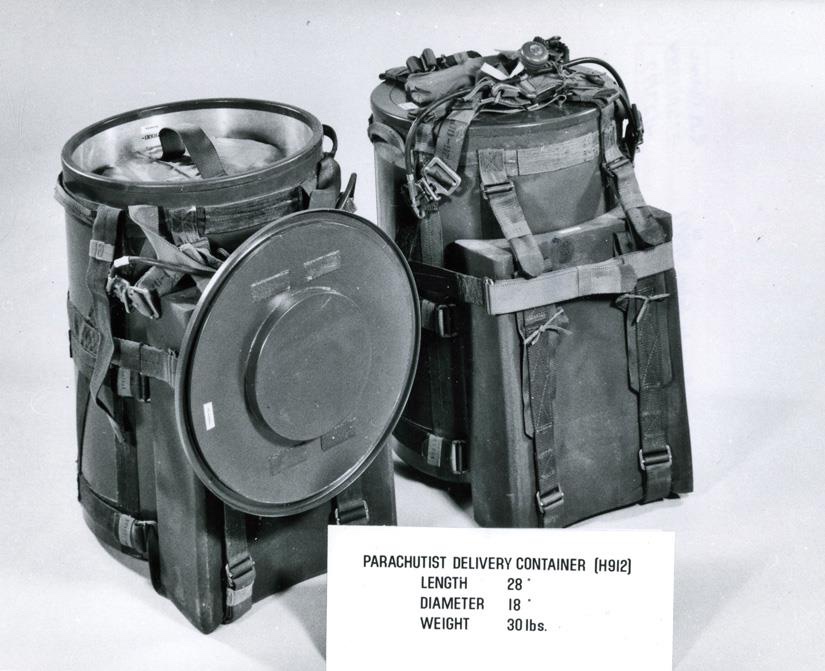

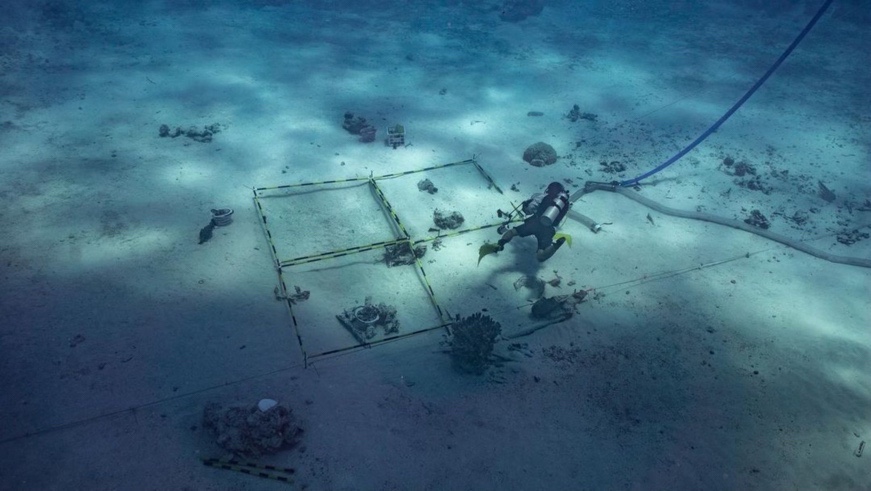

It was on station for a while during the cutting phase, all nonessential equipment was turned off, and all hands were not allowed to move from their assigned stations. Once the cable was cut, the sub started to sink from the extra weight of the cable, and the crew had to allow this to happen until they could get away from the trawler. Once they were far enough away, the Conqueror crew sent out divers to retrieve the cable after being sent to the U.S. for analysis.

According to Stuart Prebble’s book Secrets of the Conqueror, one minor miscalculation could have spelled disaster for the entire operation.

‘The control room was tense,’ said one crew member. We expected to be discovered at any time and were prepared to flee.’

The Conqueror had twice attempted to cut the cable from the boat before succeeding in August 1982. It did not take the U.S. long to realize that the cable was made to the specification as the ones used by the U.S. and U.K. It is believed that John Walker, who spied on the U.S. for the Russians from 1967-1985, was the person that gave them the information.