WASHINGTON (AFNS) —

It’s never too early to start celebrating a major milestone, which explains why the U.S. Air Force and Department of the Air Force kicked off the year with a bang Jan. 1 by highlighting the start of their 75th year at the Tournament of Roses Parade and the Rose Bowl.

Seventy-five years after the Air Force’s birth on Sept. 18, 1947, the spirit of innovation that has driven the service was on display when a B-2 Spirit from the 509th Bomb Wing, located at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, roared over the Tournament of Roses Parade and one of the most prestigious college bowl games, the 2022 Rose Bowl, to kick-off the yearlong 75th-anniversary celebration.

The B-2 has supported the Tournament of Roses and Rose Bowl for nearly two decades, showcasing one of the Air Force’s premier weapon systems over the skies of Pasadena to inspire a future generation of patriotism and aviation.

Joining the B-2 this year to kick off the celebration was an Air Force Total Force Band, comprised of 75 Airmen-Musicians from 14 units. Fittingly, the band marched in the 75th spot in the Tournament of Roses parade lineup.

The Airmen taking part in the start of the year celebration highlighted one of the service’s greatest strengths: the nearly 700,000 active duty, Guard, Reserve and civilian Airmen who remain the heart and soul of the service, said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. CQ Brown, Jr., who currently serves as the service’s highest ranking military officer.

“Ever since the Air Force became a separate military service, empowered Airmen have pushed the boundaries of technology and innovation that have allowed the service to excel and keep pace with the rapid changes and the demands placed upon us,” Brown said. “Our commemoration of this important anniversary provides a chance to reflect on the amazing accomplishments of our service and those who have served among its ranks since 1947, while also celebrating the boundless future that lies ahead.”

Brown added, “As the Air Force approaches its 75th anniversary, we have a responsibility to our nation and our international allies and partners. I am confident that our Airmen will continue to innovate, accelerate and thrive so that we can execute our mission to Fly, Fight, and Win…Airpower Anytime, Anywhere.”

To honor the past, present and future, the theme for the 75th anniversary is “Innovate, Accelerate, Thrive – The Air Force at 75.” That focus captures a range of activities and observations that will take place throughout the year and highlight the anniversary’s significance.

“The 75th anniversaries of the U.S. Air Force and the Department of the Air Force provides a unique opportunity to highlight the contributions of our Total Force Airmen, both past and present, who have fought and defended our nation in air and space,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said. “When you think about what the Air Force has accomplished since its inception in 1947, there’s so much to be proud of – it’s truly incredible.

“These past 75 years have showcased the service’s ability to adapt to any situation and provide unparalleled airpower as well as spacepower right up to the establishment of the U.S. Space Force within the Department of the Air Force in 2019,” he said. “As we look ahead to the next 75 years, we must continue to adapt and modernize so that our Airmen and Guardians have the warfighting capabilities they need to stay ahead of our pacing challenges, while also ensuring they and their families have the resources they need to thrive. One team, one fight!”

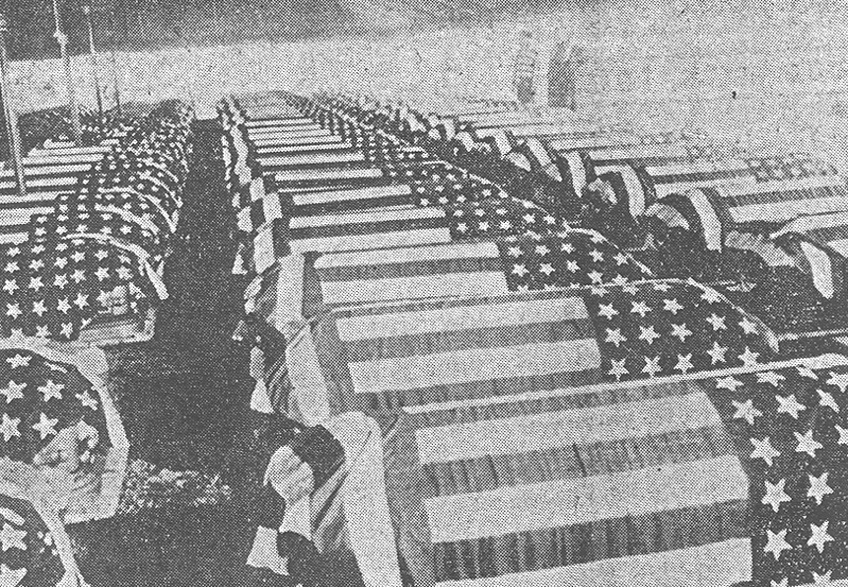

Throughout 2022, the Air Force will celebrate its 75th milestone with various events around the U.S. and worldwide to showcase the values, commitment, and expertise of America’s Total Force Airmen, past and present. In addition, the service will spotlight its history, accomplishments, and many of the pioneering Airmen whose innovation, dedication to mission, and war-fighting spirit helped established the U.S. Air Force of today.

Innovation fueled by Airmen has always been a part of the Air Force’s heritage, even before it became an independent service in 1947.

Maj. Gen. Billy Mitchell, also known as the “Father of the Air Force,” was one Airman who paved the way for the service. According to military historians, his commitment to pushing boundaries and working towards a distinct aerial service branch seeded a renaissance for the airpower legacy that would distinguish itself during conflicts across the globe for years to come.

Likewise, Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, who was designated the first and only five-star General of the Air Force by President Truman, also played a key role in leading, developing and innovating American military airpower during World War II, providing the necessary vision and drive to ultimately create the conditions for an independent U.S. Air Force following the war. Today, Gen. Arnold is considered an airpower pioneer whose efforts helped to lay the foundation for modern Air Force logistics, R&D, and operations, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

The Air Force’s history is also the history of the nation’s advancements in space. Under the Air Force’s early space pioneers such as Gen. Bernard Schriever, the Air Force developed and integrated the technologies that put U.S. rockets and satellites into space. By Operation Desert Storm in 1991, often called the nation’s first space war, space became central to nearly all military operations. These same technologies that brought victory in Desert Storm, such as GPS and communication satellites, are now essential to modern life in America. The importance of space grew to such an extent that the U.S. Space Force emerged as an independent service within the Department of the Air Force in 2019.

“This is what is being celebrated as the U.S. Air Force and the Department of the Air Force enter their 75th years and what was on display in the skies over California when the B-2 roared overhead: 75 years of American airpower, spacepower, and innovation that have secured our nation and made us stronger,” said Brig. Gen. Patrick Ryder, Department of the Air Force Public Affairs director.

Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs

Photos by Nicholas Pilch