On September 1, 2024, the U.S. Army Cyber Corps turned ten years old. Some may chuckle at the thought of this branch still teetering on the verge of adolescence compared to the more grizzled veteran branches like Infantry, Field Artillery, and Signal just to name a few. However, there is more than meets the eye with cyber, and as I communicate to my students at the U.S. Army Cyber and Electromagnetic Warfare School (which also turned ten) at Fort Eisenhower, GA, the Cyber Corps has accomplished much in its first decade. While still a pre-teen so to speak, the rate of change in this domain has always necessitated that Cyber act mature for its age. What follows is the first part of a planned series chronicling the history of the U.S. Army Cyber Corps and its school. This first essay provides a general synopsis of the emergence of cyber and how it became a key focus for the U.S. military, tracing its early connections to information warfare and operations. It also details the origins of cybersecurity, alongside the creation of Army Cyber Command and West Point’s Army Cyber Institute. Finally, a major theme of this essay focuses on the cyberspace areas of concentration developed by the Army Military Intelligence and Signal branches – setting the stage for the eventual adoption of cyber as a standalone career field for Army personnel.

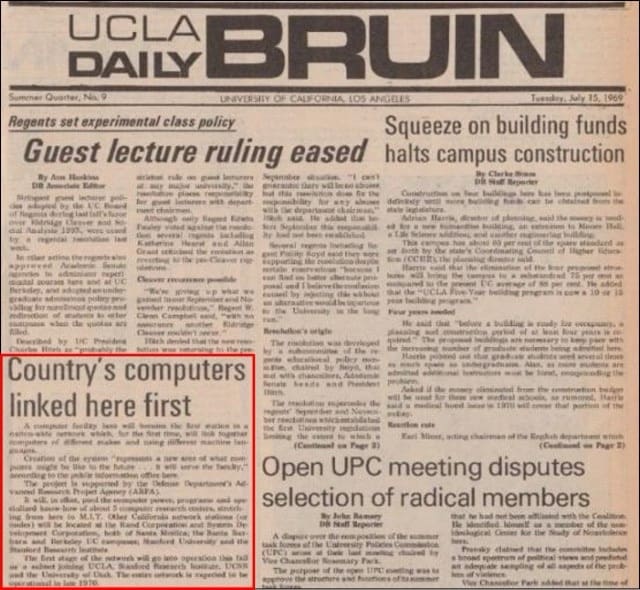

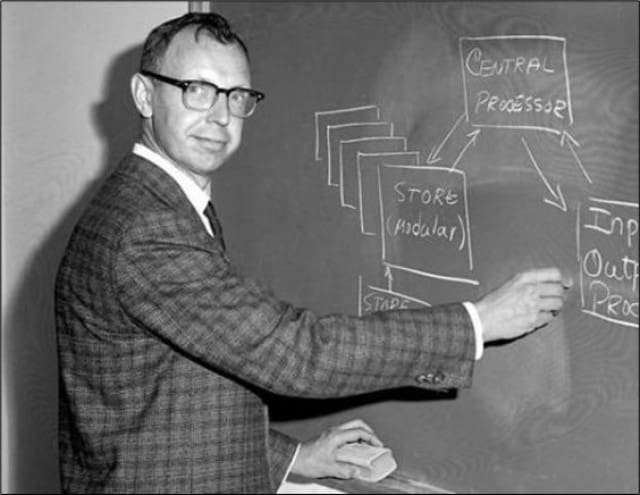

The seeds of this domain germinated in the 1960s as the U.S. military began piecing together computer networks to speed up information sharing and threat detection in the midst of the ever present Soviet nuclear threat. Additionally, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the NSA had hundreds of “internetted” terminals. It was during this environment of early networking capabilities that the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) first came online in 1969. By 1976, “Information War” as it pertained to the information flow between weapons systems and the possible digital disruption of Soviet command and control, was viewed as a worthy pursuit. By 1979, NSA leadership recognized that any computer system could be breached by a knowledgeable user, and ideas about “deep penetration” technical capabilities against U.S. adversaries began to take root. By 1986, and possibly earlier, Special Access Programs overseen by the Joint Chiefs and National Security Agency (NSA) began attempting computer network exploitation. As the opportunities for intrusion into adversary networks widened, the U.S. discovered in 1986 that the Soviets were paying hackers to engage in similar tradecraft against U.S. networks.

As the proliferation of computer networks spread globally and the ability of these computers to collect, sort, and analyze information at higher speeds, the Department of Defense (DOD) increasingly recognized the high value of information at the strategic and tactical levels of war. During the Gulf War in early 1991 (Operation Desert Storm), information played a crucial role, both in providing Allied forces with enemy intelligence and in disrupting enemy command, control, and communications. Both advantages were greatly increased by technology and computing power, and as one observer declared, “in Desert Storm, knowledge came to rival weapons and tactics in importance…” Unseen, but implicit in the glowing Desert Storm after action reports, were the information systems – “networks of computers and communications that synchronized the awesome air campaign and that turned dumb bombs into sure-kill weapons.” This set the stage for the DOD’s focus on the power of information and further exploration on the role computers could play in this sphere.

The growing emphasis on computing power and information as a force multiplier dovetailed with the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991. With a reduction in defense spending, the Army capitalized on the idea that information dominance could utilize the latest networks, systems, and sensors to gain information superiority while also economizing force in an era of reduced budgets and manpower. For the next several years, the DOD and Army produced doctrinal concepts ranging from Information Warfare, Command and Control Warfare, and Information Operations (IO). For the Army, this culminated in the activation of Land Information Warfare Activity (LIWA) in 1995 at Fort Belvoir, VA. LIWA had personnel engaging in elements of what we now call Offensive Cyberspace Operations (OCO) and Defensive Cyberspace Operations (DCO). The international peacekeeping operation in Bosnia integrated information operations personnel with maneuver staffs, and the success of these missions demonstrated the importance of IO. In order to maintain the permanence of such skilled IO staff, the Army created the first IO career field with Functional Area (FA) 30 in 1997.

While LIWA and the IO community played a large role in forming the concepts and framework of cyberspace within the Army, the Military Intelligence (MI) branch was instrumental in developing the actual cyberspace capabilities associated with OCO today. In the 1990s, the intelligence community began correlating computer network operations within foreign computer networks as another form of signal intelligence (SIGINT). With this mindset, the Army’s SIGINT brigade (704th MI BDE) created a small unit to focus on cyber warfare in 1995; in 1998, B Co, 742d MI BN was tasked to focus on computer network operations. This begat “Detachment Meade” in 2000 – a unit starting with about three dozen Soldiers. Detachment Meade retained a close relationship with LIWA, which by 2002, had been redesignated as 1st IO Command. Over the next decade, the Army OCO unit at Fort Meade grew and changed names often. By 2008, the Army Network Warfare Battalion had close to 200 members. It grew into the 744th MI Battalion and finally culminated in today’s 780th MI BDE (Cyber) in December 2011.

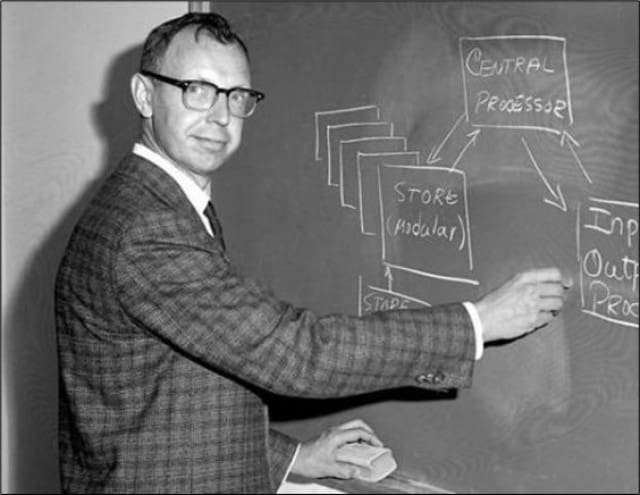

Underpinning all this cyber activity, was the vital need to maintain the security of U.S. digital property. In 1967, RAND computer scientist, Willis Ware issued a clarion call for the military to beef up security of these new networking capabilities. After becoming the Computer Security Task Force lead, Ware further warned U.S. officials in 1970 that corrupt insiders and spies could actively penetrate government computers and steal or copy classified information. In the days before computer networks were regimented into the various classifications we are familiar with today, those with prying eyes had easier access to data they had no business reading.

The Signal Corps utilized and maintained computers early on but became increasingly involved as computers became ubiquitous within the Army and essential for communications devices, whether via email or other network-centric methods. Signal’s role with network defense was emphasized after the 2002 activation of Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM), where it assumed the role of Army proponent for network defense. However, complexities within the chain of command for cyber defense kept this from being a streamlined process. Army Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) received mission priorities from NETCOM, but 1st IO Command operationally controlled the defenders. Additionally, Signal culture shaped the priorities of those working within cyber defense. Network defense and network maintenance are inherently different. The former identifies and seeks to defeat threat actors while the latter strives for information assurance through securely maintained networks and is less concerned with outside threats. The aforementioned culture of signaleers leans hard toward the goal of properly functioning networks. Network defense might hinder network assurance, and this mentality contributed to keeping the two spheres distinct.

While the Joint Chiefs of Staff labeled cyberspace a “domain” of military operations in the 2004 National Military Strategy, the Army continued mapping out its overall cyber strategy. A few years prior to this in 1998, the Army designated Space and Missile Defense Command/Army Strategic Command (SMDC/ARSTRAT) as the higher headquarters for cyberspace activity. A decade later, in 2008, the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) directed the different services to establish cyber commands, and the following year, SMDC/ARSTRAT created an interim unit called Army Forces Cyber Command (ARFORCYBER). As the various Army subcommunities already conducting different aspects of the cyber mission (INSCOM, NETCOM, SMDC/ARSTRAT) jockeyed for lead of this new interim unit, SECDEF Gates announced the creation of U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) in June 2009. Per Gates’ memo, the service branches needed to establish component commands to support USCYBERCOM by October 2010. Now the Army reoriented its focus on meeting this requirement, which resulted in the activation of Army Cyber Command (ARCYBER) as a new three-star command on October 1, 2010. The first two ARCYBER commanders held combat arms backgrounds, strongly suggesting that the Army sought leaders who could bring fresh perspectives disconnected from the tribal feuding between the intelligence and signal communities.

In the year prior to ARCYBER’s activation, the Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Commander, Gen. Martin Dempsey, released a memo in 2009 summarizing a Combined Arms Center (CAC) led working group’s findings on how the Army should organize cyber, electronic warfare (EW), and information operations. Based on the group’s analysis, Dempsey did not recommend the creation of a new cyberspace career field, opting to retain the status quo of relying on the MI and Signal fields to perform the functions of offensive and defensive cyberspace respectively. Shortly after the activation of ARCYBER and the continued lack of a separate TRADOC governed cyberspace career field, ARCYBER assumed force modernization proponency for cyberspace.

Even after the creation of ARCYBER and its authority over Army cyberspace proponency, leaders continued to favor the model whereby cyber personnel in the Army held certain Additional Skill Identifiers (ASI) that determined their roles within the cyberspace workforce. The Signal Corps and MI communities still desired more stability within this career field and opted to create new military occupational specialties (MOS) to establish more permanency. The Signal Corps looked to their warrant officer cohort to provide the technical expertise necessary to defend the Army’s portion of cyberspace. Announced in 2010, the new 255S – Information Protection Technician would perform Information Assurance and Computer Network Defense measures, including protection, detection, and reaction functions to support information superiority. The MI Branch unveiled the enlisted MOS 35Q in the Fall of 2012. Originally called the Cryptologic Network Warfare Specialist, the title later changed to Cryptologic Cyberspace Intelligence Collector. A senior enlisted advisor to the MOS stated: “A 35Q supervises and conducts full-spectrum military cryptologic digital operations to enable actions in all domains, NIPRNet as well as SIPRNet, to ensure friendly freedom of action in cyberspace and deny adversaries the same.” The Signal Corps also established an enlisted MOS, 25D – Cyber Network Defender, starting at the rank of E-6, reasoning that “an MOS built on an experienced and seasoned Information Assurance (IA) Noncommissioned Officer workforce, highly trained in Cyber Defense, is the only way to mitigate our vulnerability.” The first 25D class graduated from the Signal School in November 2013.

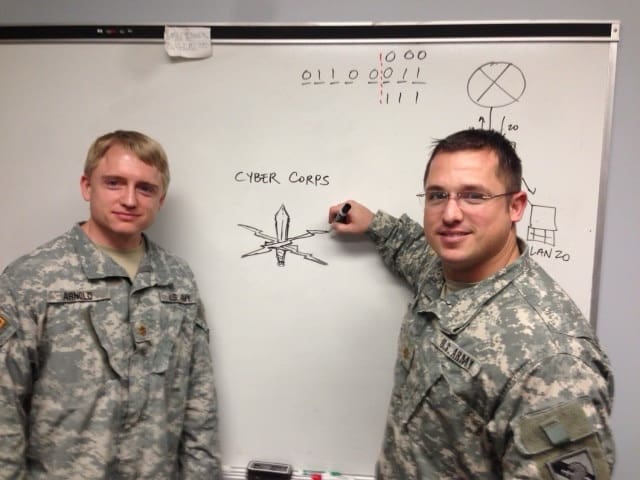

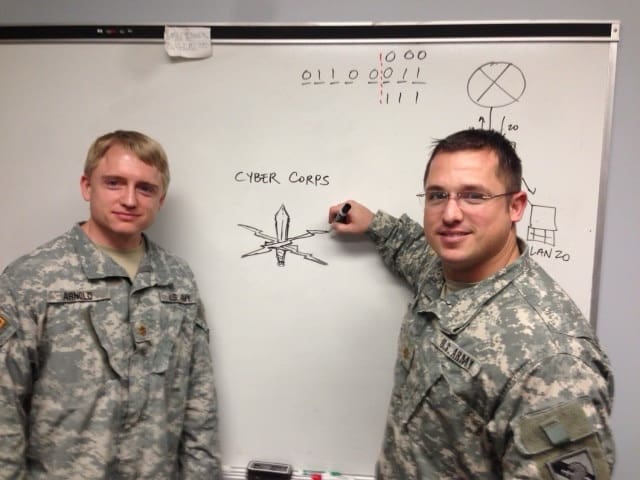

During the first decade of the 21st century, the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) Department at West Point advocated for a standalone Army cyber career field. A NSA partnership fueled cooperation and internships between the organizations, and the creation of a cadet cyber security club were just some of the initiatives moving EECS personnel towards advocacy of a new career field. Meanwhile, the EECS program continued training cadets proficient in cyberspace despite not having a branch for them to naturally land. The head of West Point’s Cyber Security Research Center, Lieutenant Colonel Gregory Conti, wrote several articles advocating and theorizing about a dedicated cyber work force within the Army. In 2010, Conti and Lt. Col. Jen Easterly contributed a piece on recruiting and retention of cyber warriors within an Army that still did not seem to understand what to do with these specialists. As a testament to the reputation of the EECS department, the Secretary of the Army in 2012 directed the establishment of a U.S. Army Cyber Center at West Point, to “serve as the Army’s premier resource for strategic insight, advice, and exceptional subject matter expertise on cyberspace-related issues.” This ultimately became the Army Cyber Institute at West Point, which officially opened in October 2014 with Col. Conti at the helm. However, before this occurred, Col. Conti and two EECS instructors, Major Todd Arnold and Major Rob Harrison, wrote a draft theorizing what an Army cyber career path might look like, specifically for officers. While they did not know whether the Army would indeed create a new branch, this detailed study covered multiple courses of action and analyzed the relationships with MI and Signal. The paper even included a proposed cyber branch insignia designed by Arnold and Harrison-with crossed lightning bolts superimposed on a dagger-which ultimately became the basis for the approved insignia.

While the West Point EECS leadership conceptualized the professionalization of a cyber career field, and the MI and Signal branches had created the aforementioned cyber related MOSs, top leadership-including Chief of Staff of the Army (CSA) General Raymond Odierno and General Robert Cone, the Commanding General of Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC)-was coming to the conclusion over the course of 2012 and 2013 that the existing split-branch solution was inadequate.

With the approval in late 2012 of the Cyber Mission Force (CMF), it became essential that personnel had the right abilities to go through a very long and exquisite training. Normally, by the time an individual completed this training, they had well over 24 months on station, and as members of the MI or Signal branches, they were often reassigned. Besides the issue of losing skilled personnel due to the normal PCS cycle, Generals Odierno and Cone, as well as many of their subordinates, felt strongly that the cyberspace domain needed to be viewed from a maneuver perspective, which was beyond the MI and Signal Corps’ normal mission set. On 20 February 2013, during an Association of the U.S. Army (AUSA) symposium in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, GEN Cone publicly called for the formal creation of a cyber school and career field. He stated the Army needed to, “start developing career paths for cyber warriors as we move to the future.” After GEN Cone’s remarks, the wheels were in motion to turn this new school and career field into reality.

Endnotes

Called the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment or SAGE, it consisted of hundreds of radars, 24 direction centers, and 3 combat centers spread throughout North America. For more information, see www.ll.mit.edu/about/history/sage-semi-automatic-ground-environment-air-defense-system.

Thomas Misa, “Computer Security Discourse at RAND, SDC, and NSA (1958–1970),” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing Volume: 38, no.4 (Oct.-Dec. 2016): 17, tjmisa.com/papers/2016_Misa_ComputerSecurity.

Researchers at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (now DARPA) created the ARPANET. By 1989, most were calling the network by a more ubiquitous name – “Internet.”

The Boeing Aerospace Company for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Weapon Systems and Information War, Thomas Rona. (Seattle, WA, 1976).

Craig J. Wiener, “Penetrate, Exploit, Disrupt, Destroy: The Rise of Computer Network Operations as a Major Military Innovation” (PhD diss., George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, 2016), 81; 85.

Wiener, “Penetrate, Exploit, Disrupt, Destroy,” 93; 98; 352.

Clifford Stoll, The Cuckoo’s Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage, (New York: Doubleday, 1989).

Alan D. Campen, ed., The First Information War: The Story of Communications, Computers, and Intelligence Systems in the Persian Gulf War (Fairfax, VA: AFCEA International, 1992), x-xi.

MAJ Sarah White, “The Origins and History of U.S. Army Information Doctrine,” (Thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2022), Chapter 5; MAJ Sarah White, Chapter 3 Edit provided to author from: “Subcultural Influence on Military Innovation: The Development of U.S. Military Cyber Doctrine” (PhD diss., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 2019).

White, Chapter 3 Edit, 12-16.

Willis Ware, “Security and Privacy in Computer Systems” (Paper presentation, Spring Joint Computer Conference, Atlantic City, April 17-19, 1967).

The RAND Corporation for the Office of the Director of Defense Research and Engineering, Security Controls for Computer Systems: Report of Defense Science Board Task Force on Computer Security, Willis Ware. (Washington D.C., 11 February 1970).

White, Chapter 3 Edit, 27-29.

Ibid., 24-26.

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Memorandum: “Establishment of a Subordinate Unified U.S. Cyber Command Under U.S. Strategic Command for Military Cyberspace Operations,” 23 June 2009.

U.S. Army Cyber Command, “Our History,” www.arcyber.army.mil/About/History.

White, “Subcultural Influence,” 133.

Ibid., 134.

CW5 Todd Boudreau, “Repurposing Signal Warrant Officers,” Army Communicator 35, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 21.

David Vergun, “Army Opens New Intelligence MOS,” Army.mil, 30 November 2012, accessed 18 October 2021, www.army.mil/article/92099/Army_opens_new_intelligence_MOS.

Craig Zimmerman, “SUBJECT: Recommended Change to DA Pam 611-21, Military Occupational Classification and Structure, to Add Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) — Cyber Network Defender,” (Signal Center of Excellence and Fort Gordon, 30 May 2012).

Wilson Rivera, “Cyberspace warriors graduate with Army’s newest military occupational specialty,” Army.mil, 13 December 2013. Accessed 20 March 2025, www.army.mil/article/116564/Cyberspace_warriors_graduate_with_Army_s_newest_military_occupational_specialty.

White, “Subcultural,” 157-160.

Lt. Col. Gregory Conti and Lt. Col. Jen Easterly, “Recruiting, Development, and Retention of Cyber Warriors Despite an Inhospitable Culture.” Small Wars Journal, 29 July 2010, smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/recruitingdevelopment-and-retention-of-cyber-warriors-despite-an-inhospitable-culture. Jen Easterly went on to become the Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) from 2021-2025.

John M. McHugh, Memorandum, “Establishment of the Army Cyber Center at West Point,” 19 October 2012.

Sgt 1st Class Jeremy Bunkley, “SecArmy officially opens Cyber Institute at West Point, Army.mil, 10 October 2014, www.army.mil/article/135961/secarmy_officially_opens_cyber_ins.

Todd Arnold, Rob Harrison, and Gregory Conti, “Professionalizing the Army’s Cyber Officer Force,” Army Cyber Center, Vol 1337 No II (23 November 2013); Email between LTC Todd Arnold and Scott Anderson, 7 November 2018.

White, Chapter 3 Edit, 36-37.

Mr. Todd Boudreau Oral History Interview with Scott Anderson, 22 February 2021.

Unknown Author, “Army leaders see much cyber work to do,” Taktik(z), 24 Feb 2013.

By Scott Anderson – Cyber Corps Branch Historian