Like many stereotypical curmudgeons, as I go about my work here on the Homestead, I spend more time than I probably should relitigating episodes of my life in my mind. Second guessing decisions made or deferred, imagining how my life’s branches and sequels might have taken a divergent course – and perhaps affected the lives of others differently. Cataloging the satisfactory and the regrettable. I suppose it is a natural – albeit inconclusive – mental exercise. Of course, it is self-evident that getting older has not made me any smarter. Over the years, I have not gained a single IQ point despite benefiting from considerable formal education, extensive advanced training, and broad life experiences. I have accumulated considerably more knowledge over time, but not any more brains. I trust that means that I am perfectly qualified to continue to offer unsolicited advice to others. I am going to keep acting like it does.

The best place to start a story is near the beginning. I served as an infantryman in West Germany from 1975 to 1978. In this article, I will start talking about that first formative year or so when I was assigned to Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry (Mechanized), of the 3rd Infantry Division (patch at top left in the picture), stationed at Kitzingen, Germany. Bravo Company of that Battalion had been Audie Murphy’s unit in WWII. The unit crest is shown in the top right corner of the picture above. The unit motto “Can Do” and the dragon date back to the early 1900s and the Regiment’s 26 years of service in China. The four acorns commemorate the major battles the Regiment fought in during the Civil War: Chattanooga, Chickamauga, Murfreesboro, and Atlanta.

Although I had been in the training pipeline for some time stateside, it is safe to say that I did not have any firsthand knowledge of the “real” Army before I got there. Still, even I quickly recognized that the Army in the mid-70s was in pretty sad shape. The Vietnam war had left deep bruises in the Officer and NCO Corps. A number who remained in uniform immediately after the war were of markedly poor quality. Morale was low for those relatively few selfless professionals that had stayed on to rebuild. The draft had ended in 1973. In fact, at Fort Polk, I had in-processed as the last draftees were out-processing. One of them tried to convince me that he was naturally a better quality soldier than I was because he made the Army “come after him.” It was an interesting perspective, but it was not just him. Indeed, VOLAR – or the “Volunteer Army” – was an experiment that most of the leadership expected to fail. In 1975, there was not one leader in the Army that had ever served in an entirely all-volunteer force. Side note: eventually, I observed that the airborne qualified NCOs in my rifle company – who had grown up in always volunteer Airborne units – generally dealt with soldiers more positively as junior teammates. “Leg” NCOs, having grown up principally with draftees, tended to foster a more “us vs them” adversarial relationship with their soldiers.

I got off a chartered commercial plane at Rhein-Main Air Base in September. It was an ordeal that lasted several days to get from there to an actual unit. First, soldiers processed through the theater replacement center on the airfield. Then on to the Division of assignment. There were four complete Army Divisions stationed in Germany at the time and “Forward Brigades” of two other divisions. Not to mention two Corps HQs and an Army HQ and all the ancillary organizations – some 300,000 U.S. soldiers in all distributed throughout the country. In my case, I passed through the 3rd ID Replacement Detachment at Wurzburg, Germany, and then to my battalion in Kitzingen. I got there just in time for REFORGER 1975. In fact, when I got there, part of the unit had already moved out to a staging area. Therefore, I was not immediately assigned to a platoon and barely had enough time to draw my gear (no CIFs in those days, we got our TA50 from our Company Supply Room) before I was heading to the field in the back of a Deuce and a half.

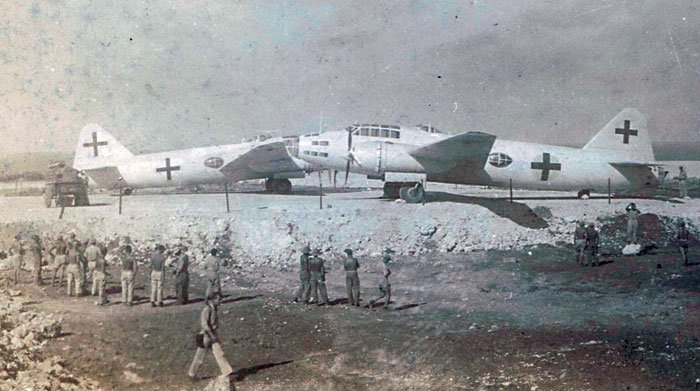

As it turned out, the REFORGER exercises served to bookend – and in some sense define – my tour in Germany. In 1975 it was my first experience. I also played in the 1976 and 1977 iterations. REFORGER 1978 was my last time in the field before I was reassigned to Fort Lewis. REFORGER is an acronym for Return of Forces to Germany (RE-FOR-GER). It involved thousands of soldiers deploying from home stations in the U.S. to fall in on pre-positioned equipment warehoused in Germany, and then participate in a large-scale force-on-force wargame involving German-based American units as well as NATO Allies including the West Germans. Getting the forces from CONUS and drawing equipment was actually the most important strategic element of the exercise. The follow-on wargame itself was mostly for show; both to visibly reassure allies and the German population of our commitment and to – hopefully – deter the Soviet Union from invading. The picture above is from REFORGER 1982, but it perfectly captures the dynamics of the exercise I want to highlight below.

A large-scale, free play training exercise like REFORGER requires a lot of overhead. My new unit was going to play in the wargame; while I, and several others, got detailed to support the exercise Umpires. Umpires were only there to move the wargame along by adjudicating engagements (no MILES lasers in those days). They did not evaluate or provide feedback to the units like Observer Controllers do today. Since I did not know much of anything, I had a simple task. An NCO would drop a couple of us off with some water, a case of C-Rations, and wooden signs saying “OBSTACLE.” Whenever a unit approached us, we would inform them, via pre-printed and laminated 3×5 Cards, as to the nature of the obstacle. For example, a minefield or tank ditch – and how long it would take to reduce the obstacle once engineer assets were on site. Of course, an Umpire would show up about this time to keep everyone honest and assess casualties on both sides if the obstacle was defended as most – but not all – were. Then, as the units maneuvered through that obstacle, we would be moved to another location and do it all over again.

This routine went on for most of two weeks. Sometimes we were in place for only a couple of hours; however, in one case, we saw no one for two days because the “war’ had moved in a different direction and that particular notional obstacle had been bypassed with no contact between forces. The engagements themselves were anticlimactic, to say the least. Both sides would fire a few blanks, count coup, and the “losing” side would move off. As I recall, the weather was not too bad, the days were warm enough to go without field jackets and we were able to make fires most nights to ward off the chill. Still, I was in a foreign country and many of the fake obstacles were adjacent to – and even inside – the small towns. We had the German civilians – especially children – to interact with. Thankfully, they knew more English than I did German. I was surprised by how friendly they were, and how they took the major inconvenience of the wargames in stride. During that time, the West Germans took the Cold War and a Soviet invasion very seriously. Indeed, they knew a lot more about the threat than I did at that point.

Later, I became fairly familiar with the practical implications of the strategic “Mutually Assured Destruction” policy adopted by both sides in the Cold War. Elements of that doctrine are still in effect today – albeit not maintained at quite the same level of urgency. Those of us stationed in Germany in the 1970s fully expected to be in a no mercy, no quarter, no prisoners, and – ultimately – no win fight with the Soviet Armies in the vicinity of the famous “Fulda Gap” if war came. We also expected that whatever feats of collective valor or personal heroism or any tactical success we might achieve on the battlefield would be meaningless and unknown to history. Tactical nukes – including short-range tube artillery, and Atomic Demolition Munitions (ADMs) – were expected to be employed within the first couple of days. It did not matter which side used them first because the other would respond in kind immediately. And none of that mattered, because shortly after that line had been crossed, we would very likely have witnessed the contrails of the ICBMs of both sides being launched. So, within days of the initiation of hostilities, those at home that we were supposed to be defending would be dead. Barring a highly unlikely battlefield miracle, that was indeed the plan. I never liked that plan.

In any case, I was oblivious to all of that in the Fall of 1975. I actually enjoyed my tour of the German countryside and my brief cultural immersion. I even picked up a few words of German. What I did not get, was any professional development. I had only the vaguest understanding of what was happening. I do not think anyone ever took any time to explain what the exercise was supposed to accomplish. I had no map or compass and no clear idea where I was at any point. The soldiers I was partnered with were just as clueless. I did not know if the 3rd Infantry Division, or my Battalion, were playing good guys or bad guys in the wargame. I had no idea what patches represented Germany-based units or who the rotational units were. At the time I just thought that was how the Army rolled. Granted, no one needed to waste their time explaining the history of the Cold War and the geopolitical implications of the REFORGER series to PFC Baldwin. I was clearly not ready for that. However, I could have potentially contributed a lot more if I had been told how my role – no matter how small – fit into the bigger picture.

I found out that I hated to be in the dark. Later, I learned that most soldiers hate that. The more I knew about whatever mission was at hand, the more I wanted to know. Additionally, I learned that the more soldiers know about the mission the better they tended to perform. If anything, I came to believe in what some call “over communications.” As I practiced it, that meant routinely giving people more information than they might need immediately at their grade. Of course, a leader still does not want to swamp that PFC with more “strategic” level data than he or she can reasonably process or use. However, I have rarely found that there is any good reason to withhold any tactically relevant information from my subordinates. If you believe knowledge is power – and I do – then the more every member of the unit knows the better the chances for mission success.

I am going to take a couple of paragraphs to talk about tactical gear in those days. The Army was much more frugal then. Even the newest gear I was issued in Germany dated from the mid-1960s. I was issued an M1951 Field Jacket manufactured in 1958. So faded that it was practically white. But it was still “serviceable” so they kept issuing it. A mess kit with utensils and canteen cup all from the 1950s; and a Shelter Half with buttons not snaps from 1948. Although I did not yet know it, the M1956 Load Carrying Equipment (LCE) I was issued was already being slowly replaced with ALICE gear. I had only seen M1956 gear in training and did not see any ALICE until I got to Fort Lewis in the late Fall of 1978. We had no rucksacks in Germany. The nylon and aluminum Lightweight or Tropical Rucksacks had been special issue in Vietnam but were not authorized in temperate zone assignments.

Units literally could not even request items not already on their property books. If it had not already been issued, it was not authorized. To get a replacement, a Supply Sergeant had to first turn in some unserviceable remnant of the item to be replaced. There was no such thing as unit purchases either. I have attached a couple of pictures for those unfamiliar with M1956 LCE. At the bottom are five stalwart young troopers probably at some training base in CONUS. I am not one of them, but that is how I looked during REFORGER. We had the two-sided “Mitchell” camouflaged helmet covers with a brown side and a green side. These guys have the green side out. I probably had the brown side out during the exercise but I cannot swear to it. Change over dates were put out at the highest level and soldiers all switched on cue – regardless of the status of the surrounding vegetation.

On the top right (above) is a picture of the LCE as it appears in the manuals of the day like FM 21-15, Care and Use of Individual Clothing and Equipment. It shows the harness set up as a six-point system with the ammo pouch attachment straps spread out from the front suspender straps. That is not how it was normally worn. With three 20-round M16 magazines in the ammo pouch and a grenade or two mounted on the sides of the pouches, there was quite a bit of weight that needed to be counterbalanced. Most everyone aligned the ammo pouches with the suspenders with both straps running more or less down the center of the uniform pockets as you see in the top left picture. With a couple of C-Rations, a change of socks, and a poncho in the buttpack on the back the load balanced out quite well.

However, there was not a lot of free real estate on the belt or harness once both ammo pouches, a buttpack, canteen, entrenching tool, flashlight, and first aid pouch are added. That is why in the M1956 system, the bayonet piggybacks off the E-Tool in the picture. Again, despite what the manuals said, I never saw anyone set up their gear this way. In the Mechanized Infantry, we used the M113 Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) as our foxholes. The E-Tool was stowed in the duffel bag on the side or top of the track and rarely used. We just wore the bayonet directly attached to the left side of the belt instead. By the way, it did not matter if you were right or left-handed. The unit SOP and uniformity dictated which side the canteen and bayonet were required to be carried. Most SOPs were based on the pictures in the manuals – canteen on the right, E-Tool and/or bayonet on the left.

Furthermore, if you wore the M1956 E-Tool as shown it would beat your thighs black and blue in short order – even just walking at a quick pace. There was only one time when I remember mounting the E-Tool on my LCE. We were required to wear all the LCE components for the EIB 12 Mile Roadmarch. We turned the E-Tool carrier upside down and tied the handle as tight as we could to the suspenders. It was not entirely satisfactory, but was better than doing it “by the book.” We had to work with what we had. Back in the day, there was no such thing as an after-market gear source so options were limited to adapting what was issued. I have mentioned before that the Airborne Units of WWII famously used their organic Rigger detachments to manufacture Airborne specific items that did not exist in the Army supply system. To the Army’s credit, the post-Korean War M1956 system was well thought out, fairly comfortable, and, therefore, generally popular with the troops. Indeed, it was more comfortable than the follow-on ALICE harness. M1956 gear served as a system throughout the Vietnam War and some individual items – like buttpacks – soldiered on for a couple more decades after that. However, the fact that “extra” M1956 parts were not readily available to soldiers served to limit opportunities to hack or supplement that generation of tactical gear in any way.

Jumping ahead, ALICE gear was treated differently by the Army. The most important change was that the Army decided, unlike previous “field gear” items, to make ALICE components available at Clothing Sales Stores (CSS) for individual soldier purchase. And ALICE items were cheap. $4.00 for the Y-suspenders/ shoulder straps as I recall. Now soldiers finally had the option to buy more than they were issued. That meant even privates could have one clean new set for parades and another for the field. It meant that troopers could experiment and make adjustments to their gear in ways we could not with M1956 – adding extra ammo pouches for example. Concurrently, non-issue ALICE compatible items began to appear on the market from companies like Eagle, Blackhawk, and Brigade Quartermasters. I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that ALICE and that CSS decision by the Army gave birth to the extensive tactical gear industry we know today.

I know a lot more now about how things work than I did then. Our M1956 LCE was already obsolescent in 1975 but still worked pretty well. We had battle-tested major end items like the M60A1 tanks shown in the first picture, and M113A1 APCs and UH1 Huey and Cobra Helicopters. We had a good number of truly great NCOs and Officers with extensive combat experience. Unfortunately, we had quite a few more that were not up to the Herculean challenge of rebuilding the Army after Vietnam. We had serious “indiscipline” problems and drug and alcohol abuse were endemic. A week after we got back to Kitzingen from REFORGER, two soldiers in my company overdosed on Heroin and died in the barracks. As Dorothy said, I was not in Kansas anymore. Like it or not, it was my Army now too.

De Oppresso Liber!?

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.