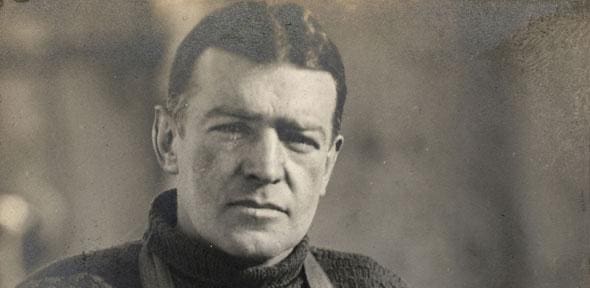

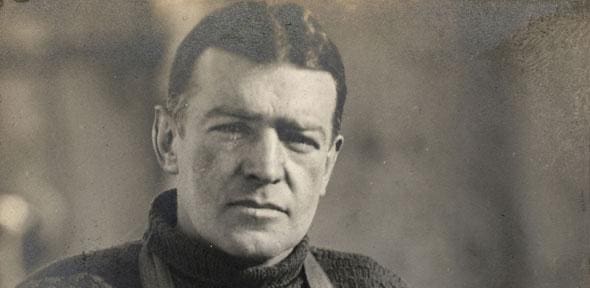

On 5 December 1914, the HMS Endurance left South Georgia for Antarctica, carrying 27 men (plus one stowaway who became the ship’s steward), 69 puppies, and a tomcat named, Mrs. Chippy. The goal of expedition leader Shackleton, who had once agonizingly fallen short of reaching the South Pole twice, was to establish a base on Antarctica’s Weddell Sea coast.

From there, on the first crossing of the continent, a small party, including himself, would eventually arrive at the Ross Sea, south of New Zealand, where another group would be waiting for them, having set up food and fuel depots along the way. Endurance joined the pack ice two days after leaving South Georgia, the barrier of dense sea ice standing guard across the Antarctic continent. The ship pushed its way through leads in the ice for several weeks, gingerly working its way south, but on 18 January, a northern gale jammed the pack hard against the ground and tightly squeezed the floes against each other. There was suddenly no way forward, nor any way back.

They were sailing from their landing place within a day; now, with each passing day, the ice’s drift was slowly moving them farther south. Nothing else could’ve been done but to create a routine and wait for the winter.

The crew saved as many provisions as they could in the time that passed between abandoning Resilience and watching the ice swallow it up entirely while sacrificing anything and anything that added weight or consumed valuable resources, including bibles, books, clothes, instruments, and keepsakes.

The original plan was to march toward the land through the ice, but that was abandoned after the men accomplished just seven and a half miles in seven days. There was no alternative,” Shackleton wrote, “except to camp on the floe again and to possess our souls with what patience we could until conditions would become more favorable for a revival of the attempt to escape.” The ice drifted further north slowly and steadily, and the snow-capped peaks of Clarence and Elephant Islands came into view on 7 April 1916, flooding them with hope.”

“The floe was a good friend to us,” Shackleton wrote in his diary, “but it has reached the end of its journey and is now obliged to break up at any moment.”

It did precisely that on 9 April, breaking with an almighty crack underneath them. Shackleton gave the order to break camp and launch the ships, and all of a sudden, they were finally free of the ice that had alternately surrounded them and supported them.

Now they had to deal with a new foe: the open ocean. It poured icy spray on their faces and threw cold water over them, beating the boats from side to side, and as they fought the elements and seasickness, it took brave men to the fetal position.

Captain Worsley navigated through the spray and the squalls through all of it before Clarence and Elephant Islands emerged just 30 miles ahead after six days at sea. The men had become tired. Worsley had not slept for 80 hours by that time. And although some have been crippled by seasickness, some have been wracked by dysentery. Frank Wild, the second-in-command of Shackleton, wrote that “at least half the party was insane.” But they rowed resolutely toward their target, and they clambered ashore on Elephant Island on 15 April.

They were on dry land for the first time since leaving South Georgia 497 days ago. Their ordeal was far from over, however. After nine days of healing and training, Shackleton, Worsley, and four others set out on one of the lifeboats, the James Caird, to seek aid from a whaling station in South Georgia, more than 800 miles away. The chance of someone coming across them was vanishingly slight.

They fought monstrous swells and furious winds for 16 days, blowing water out of the ships and beating ice out of the sails. Shackleton recorded, “The boat tossed endlessly at the great waves under grey, threatening skies.” Each surge of the sea was an adversary to be watched and circumvented.” The elements hurled their worst at them even as they were within touching distance of their goal: “The wind screamed as it ripped the tops off the waves,” Shackleton wrote.” “Our little boat swung down into valleys, up to tossing heights, straining till her seams opened.”

The wind eased off the next day, and they made it ashore. Help was nearly at hand, but this was not the end, either. The winds had driven the James Caird off course, and from the whaling station, they had landed on the other side of the island. And so Shackleton, Worsley, and Tom Crean set out to reach it by foot, scrambling over mountains and sliding down glaciers, forging a route that no human being had ever forged before they stumbled into the station at Stromness after 36 hours of desperate hiking.

In no possible circumstances could three strangers possibly arrive at the whaling station from nowhere, definitely not from the mountains’ direction. And yet here they were: their stringy and matted hair and beards, their faces blackened with blubber stove soot, and creased from almost two years of tension and deprivation.

And the old Norwegian whaler remembered the scene when the three men stood in front of Thoralf Sørlle, the station manager:

The boss would say, “Who the hell are you?” ‘And in the middle of the three, the awful bearded man says very quietly:’ My name is Shackleton.’ I turn away and weep.’

Once the other three James Caird members were rescued, attention turned to the rescue of the remaining 22 men on Elephant Island. Yet, despite all that had gone before, this final mission proved to be the most challenging and time-consuming of all in many respects. Although attempting to cross the pack ice, the first ship on which Shackleton set out ran dangerously low on fuel and was forced to turn back to the Falkland Islands. The government of Uruguay provided a vessel that came within 100 miles of Elephant Island before being beaten back by the ice.

Every morning on Elephant Island, Frank Wild, left in charge by Shackleton, issued an appeal for everyone to “lash up and stow up” their belongings. Might the boss come today! “He proclaimed every day. His friends became increasingly bleak and questionable. Macklin reported on 16 August 1916, “Eagerly on the lookout for the relief ship.” “The hope of her coming was quite abandoned by some of the party.” Orde-Lees was one of them. “There is no longer any good in deceiving ourselves,” he wrote.

But Shackleton acquired from Chile a third ship, the Yelcho; eventually, on 30 August 1916, the Endurance saga and its crew came to an end. When they spied the Yelcho just off the shore, the men on the island were settling down to a lunch of boiled seal’s backbone. It had been 128 days since James Caird’s departure; everyone ashore had broken camp within an hour of the Yelcho emerging and left Elephant Island behind. Every one of the Endurance crew was alive and healthy twenty months after setting out for the Antarctic.

Never did Ernest Shackleton reach the South Pole or traverse the Antarctic. Another expedition to the Antarctic was initiated, but the Endurance veterans who accompanied him found that he seemed smaller, more timid, drained from the spirit that kept them alive. On 5 January 1922, he had a heart attack on a ship in South Georgia and died in his bunk. He was a mere 47.

Wild took the ship to Antarctica with his death, but it proved inadequate to the task, and he set course for Elephant Island after a month spent futilely trying to penetrate the pack. He and his comrades, from the safety of the deck, peered through binoculars at the beach where so many of them had been living in fear and hope.

“Once again, I see old faces and hear old voices, old friends scattered all over,” Macklin wrote. “It is impossible, however, to express all I feel.”

And with that, one last time, they turned north and went home.