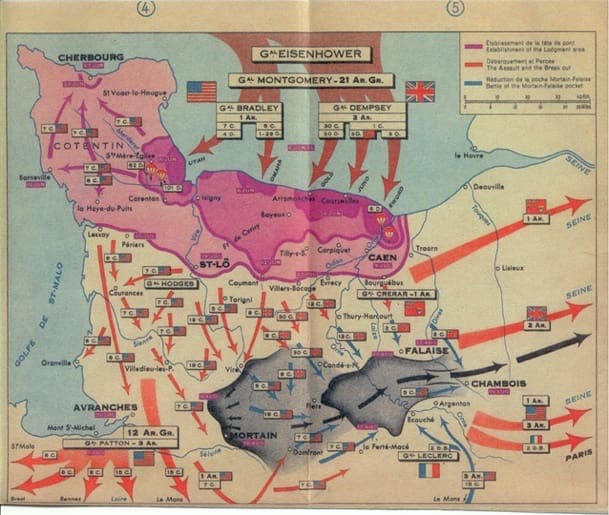

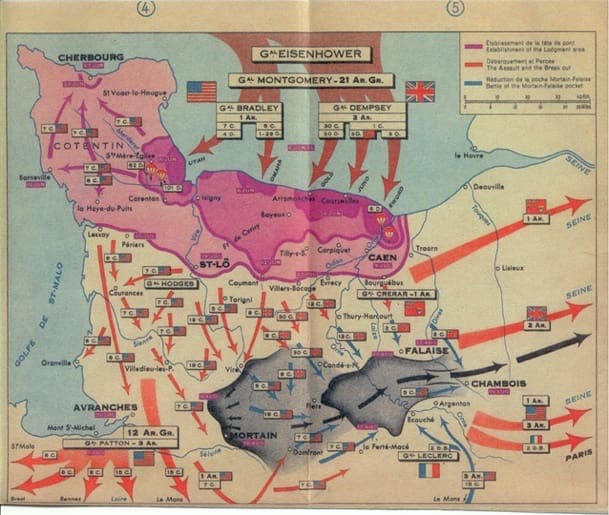

When most people think of Normandy, they think about the invasion on 6 June, and leave it there. But the Battle of Normandy did not end until 29 August when the last German troops crossed the Seine river. The Allies had estimated the casualties on D-day could be as many as 40,000, but they were far fewer – around 10,000. Even on Omaha Beach, the Allies lost about 842 dead. But it could have been a lot worse. German casualty numbers on D-Day are not as precise, but estimates put them at a similar amount. By the end of the battle, the Allies would have over 2,850,000 soldiers on the ground in Europe.

Overlord was the code name for the invasion. The first six weeks had come to a stalemate, an operation on 18 July by the U.K. forces known as GOODWILL did advance them about 10 square miles, but it came at the cost of over 5500 Allies casualties, and about 400 tanks lost. The Germany losses were about 100 tanks and about 200 people captured. It is conceded by many the biggest tank battle fought by the U.K.

General Bradley’s idea was named Operation Cobra, and it was put into motion on 10 July. It started with the carpet bombing of a 4-mile-long line in front of the Germans along the U.S. lines. As soon as the bombs were dropped, the U.S. 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions would punch a hole through the German defenders and finally break out of the peninsula.

As the Allied forces advanced in all directions, the German divisions tried desperately to reorganize. Patton’s 3rd Army advanced towards the east of France during the weeks that follow, only being slowed down because they were outrunning their supply of fuel and ammo. Now the Allies could pursue the Germans into the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany.

This battle would set the tone for the rest of the war, Germany lost about one battalion worth of man a week to death and injury as they retreated about 50,000 German soldiers. They also had approximately 200,000 men captured. The Allies lost more than 36,000 soldiers, and the fighting had also affected civilians living in Normandy; about 20,000 people killed, and around 300,000 homes destroyed.

Overall, the Normandy campaign was one of the most brutal of the war. The combined average daily casualty rate on each of the 77 days of the battle was 6,675: higher than the Somme, Passchendaele, and Verdun in the First World War. The Battle of Normandy was a decisive first step in the liberation of Europe.

###I want to add a note about the number and dates I have used for this article. You can ready about this campaign, and you will get different numbers and dates, depending on who wrote it and when. To this day, the numbers are still changing.

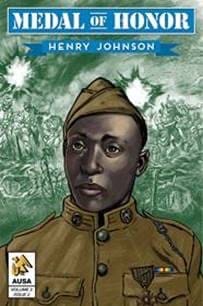

Henry Johnson served on the Western Front of the First World War as member of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an African American unit that later became famous as the Harlem Hellfighters. While on sentry duty, Johnson fought off a German raiding party in hand-to-hand combat, despite being seriously injured. He was the first American to receive a Croix de Guerre with a golden palm, France’s highest award for bravery, and became a national hero back home.

Henry Johnson served on the Western Front of the First World War as member of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an African American unit that later became famous as the Harlem Hellfighters. While on sentry duty, Johnson fought off a German raiding party in hand-to-hand combat, despite being seriously injured. He was the first American to receive a Croix de Guerre with a golden palm, France’s highest award for bravery, and became a national hero back home.