FORT BRAGG, N.C. — With the arrival of a new year, part of a new command vision will soon take place in the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) footprint.

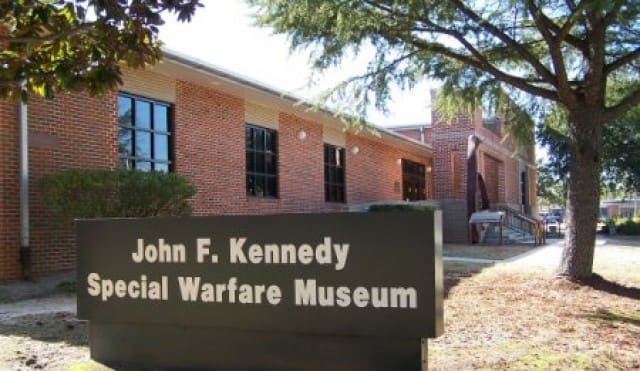

The U.S. Army Special Operations Command initiated a plan to reinvigorate the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Museum. As a result, the museum is temporarily closed to the public while a complete historical inventory is conducted to identify and catalogue items. This will ensure a better understanding of the state of artifacts available to students and Soldiers, and to identify gaps in the history of Special Forces (SF), Civil Affairs (CA) and Psychological Operations (PSYOP).

Upon reopening, tentatively at the end of February, the former U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Museum will be renamed as the U.S. Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) Museum. It will still provide support to the Special Warfare Center and Schools as well as all of the subordinate commands and units under the USASOC umbrella.

“The former SWCS Museum, now the ARSOF Museum, has been reorganized under USASOC to fully represent all of USASOC’s equities,” said Dr. Michael Krivdo, U.S. Special Army Operations Command Historian.

The idea of the reorganization is to take ownership of ARSOF’s proud history and to get artifacts into the hands of Soldiers by intellectually engaging students and Soldiers in areas where they congregate. It is intended to keep artifacts on display engaging, relevant, and fresh.

“Where the ‘old’ museum construct focused only on artifacts and displays at one fixed location, and only featured SF, CA, and PSYOP, the ‘new’ reorganized museum provides museum support for all the subordinate units which fall within the whole ARSOF enterprise,” Krivdo added.

“The ARSOF Museum will expand to include artifacts and exhibits of the Ranger Regiment and the Army Special Operations Aviation Command, which were previously not included in the current museum as it was tied to the regiments that are assessed, trained and educated at SWCS; these are the Green Berets, PSYOP and CA Soldiers,” said Janice Burton, a spokesperson for the Special Warfare Center and School.

Staff Sgt. Keren Solano, a spokesperson for the Special Warfare Center and School said, “It also serves to illustrate the unique and specialized part played by all aspects of the Army Special Operations community both in conflict and during crucial roles in peacetime. The museum has also proven itself to be a valuable recruiting catalyst.”

The updated look and feel of the U.S. Army Special Operations Forces Museum will leverage technology by making displays hands-on and ideally, three dimensional. Active duty students and Soldiers are the ‘center of the bullseye’ as the target audience. The content will focus on informing and educating them about the dynamic history of Army Special Operations.

“This would not only include students, Soldiers assigned to operational units, and support units, but their families and retirees as well,” she added.

With the museum set to have a new name and broader scope of information, U.S. Army Special Operations Command is setting the stage for the implementation of a vision of immersing Soldiers and students in the organizational heritage and history.

By SGT Larry Barnhill, USASOC Public Affairs Office