Based on unit requests SOTech has introduced a PALS compatible Pouch for the Magpul D-60 5.56 drum

They are ready to adapt the Pouch to the larger D-50 drum for 7.62 ammo once it begins to hit the field.

Team Wendy has introduced a new communications system called C2 or Comms Controller.

They partnered with a leader in the communications industry to create a proprietary designed in-ear communications system that serves as a solid complement to their helmet system. The initial focus of the system will be for SAR communities.

C2 consists of in-ear headset, control box, dual comm splitter, Motorola APX adapter, and Smartphone adapter.

C2 not only offers dual comm capability with independant volume and push-to-talk, but also a noise re-education rating of 25dB. It also incorporates impulse noise protection and extended sound localization.

It operates for 40 hours on a AAA battery as well as drawing power from the radio.

C2 is intended for use by LE, first responder and SAR teams. As you can see, it is available with a PALS compatible chest rig which will carry a radio as well as other items.

The front can easily be dropped forward to access checklists, admin items or even smartphones.

The rear yoke offers attachment for other items as well.

Made from Polartec’s heaviest weight Powerstretch, it features a nylon face to reduce pilling.

Featuring classic three button styling, it also incorporates thumb holes.

The BRN-180 is the latest product from Brownells’ Retro line. It’s an upper receiver group designed for use with AR-15-style lowers but use the piston operating system from the AR-180, including the reciprocating side charging handle.

Naturally, this means that it doesn’t require the AR’s action spring and buffer to function, making use of a folding stock a cinch.

It features an original 3-prong flash hider, M-LOK handguard and a barrel with 223 Wylde chamber and 1/8 twist.

Shipping on April, the Force-On-Force Mandible from Ops-Core incorporates a removable mesh neck skirt. Additionally, the mandible itself connects via the ARC rail and is adjustable fire and aft as well as up and down.

It stops up to the 7.62 UTM round at 375 FPS but you’ll still feel the hit.

The Laser Early Warning Detection System is one of those technologies that is going to save lives. In fact, it was developed by Attollo Engineering from their OMNir technology at the direction of Air Force Research Labs because of a friendly fire incident in Afghanistan where a US aircraft mistakenly bombed US troops.

LEWDS is lightweight and mounts to the top of the helmet or other equipment. It uses a common CR123A battery.

It offers a haptic alert (user programmable) if it is lased with 1064 & 1550nm energy which is generated by:

– Low Eye-safe military laser rangefinders (LRFs) used for precision target locating

– Low frequency gimbal-mounted LRFs

– High frequency handheld LRFs

– PRF-coded Laser Target Markers (LTMs) used for handoff to laser designator systems

– PRF-coded Laser Target Designators

(LTDs) used for guiding laser guided bombs

In addition to direct targeting LEWDS also detects “Danger Close” illumination and is designed to reject false alarms.

LEWDS does not need to be fielded to all. Because it detects Laser energy generated from above, Terminal Attack Controllers and small unit leaders are the best use of the device as they are most likely to have contact with Close Air Support aircraft to alert them they are placing friendly troops in danger.

LEWDS is available from www.quanticotactical.com.

January 23, 2019

Redmond, Oregon

Radian Weapons is pleased to announce that its new Raptor/Talon Competition series will be present at the Radian booth, #959, during SHOT Show 2019.

The new lineup features Radian’s classic Raptor/Talon design and is built with aircraft grade 7075 aluminum, with Type III hard anodized handles. The new additions to our accessory line come in both red and blue – perfect for the action match shooter who wants to upgrade their build! Like all Raptors and Talons, they are Made in the USA.

Like its predecessors, this Raptor is truly revolutionary in design and function. Its fluid designed designed to streamline motion and increase manipulation speed. Rapid palm blading or finger-thumb charges are fast whether from the support or “strong” side. Don’t forget you will receive a discount on a Talon Safety Selector if purchased along with a Raptor Charging handle.

Learn more by connecting with Radian on social, @radianweapons on Instagram, @radianweapons on Twitter, and on Facebook, /RadianWeapons/. Or, you couldjust go straight to site the and buy one. That would probably be best (and you’ll thank yourself later).

If you’re at the NSSF SHOT Show, come and see us!

Radian Weapon Systems is dedicated to excellence in firearms design and manufacturing. Home of the Raptor charging handle, Talon safety, Model 1 rifle series and numerous top-tier rifle accessories.

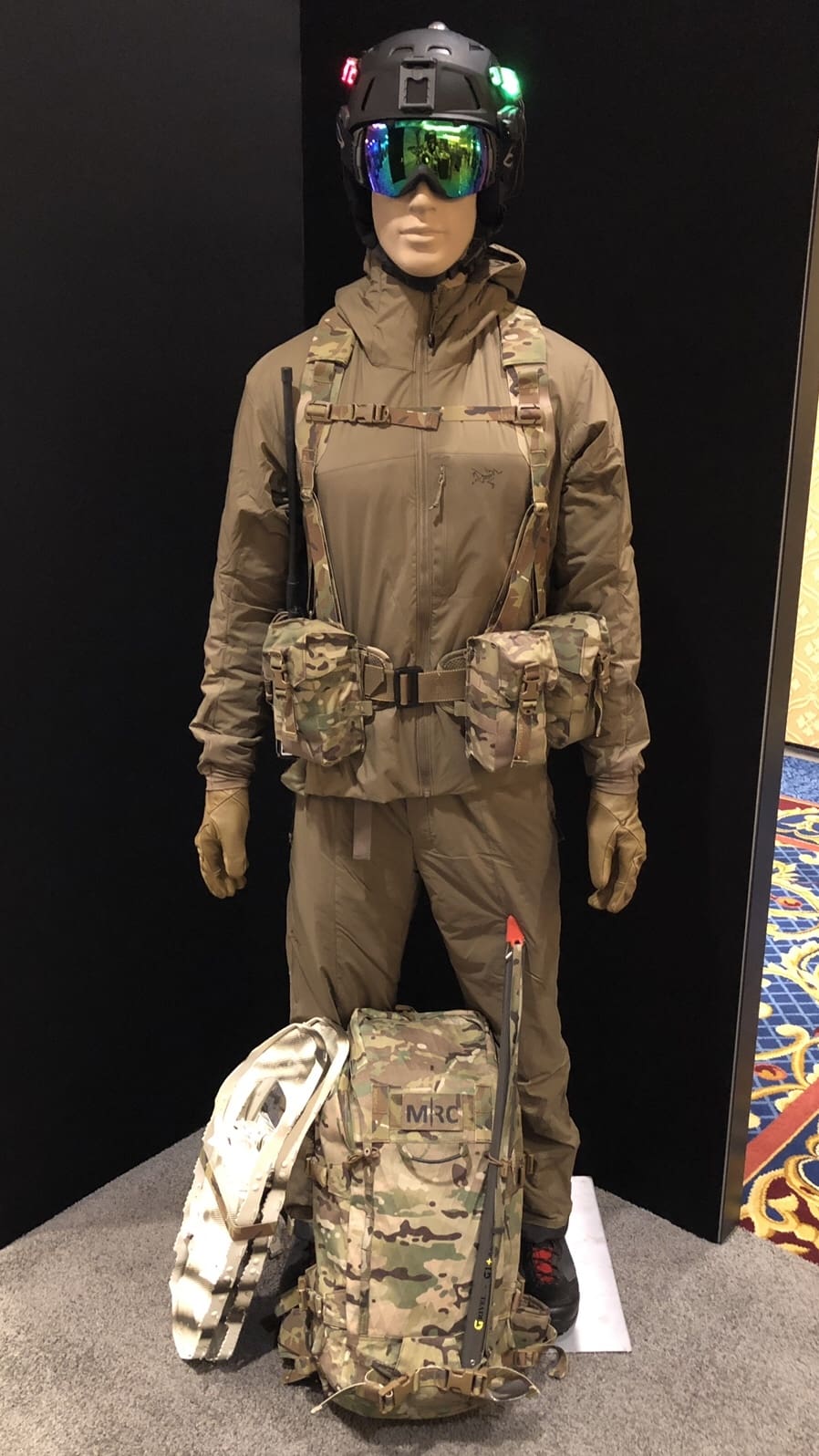

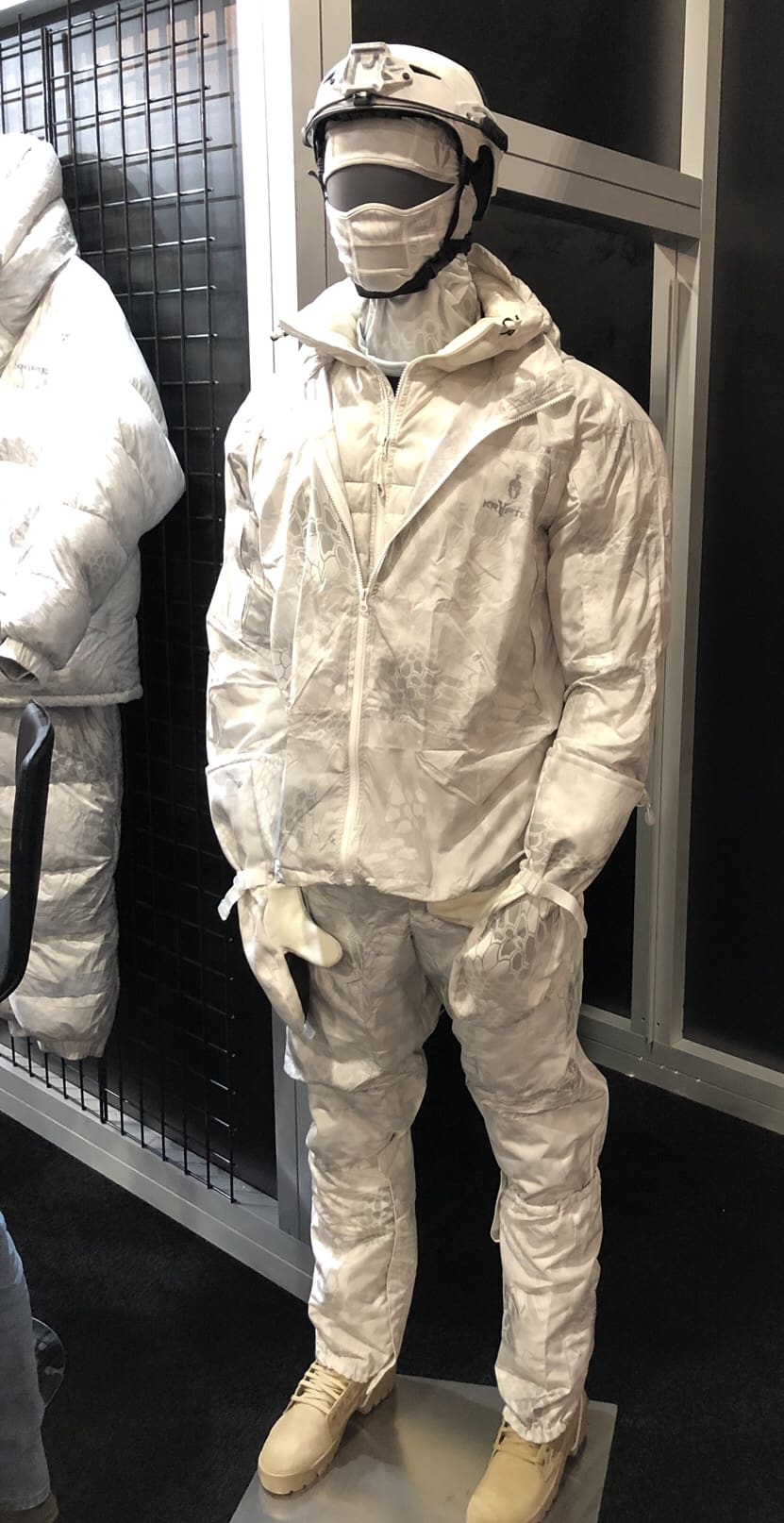

Lots of companies employ manikins in their booth. This post features some of my favorites.