We received this info from a sponsor who asked if we could share it.

Hello Dear Friends,

My name is John Mumby and I am a proud Gulf War Veteran from Operation Desert Storm (1990- 1991). I would like to take a moment of your time to share with you the lasting effects of what is called “Gulf War Syndrome”. In the spring of 2020, I started developing neuromuscular and skeletal symptoms from the inhalation of Saran gas and other chemical agents due to improper exposure and disposal during the war. These symptoms are debilitating and chronic and have taken me out of the work force like so many other Gulf war vets. The hardest part about this is I have passed on progressive debilitating health issues to three of my children.

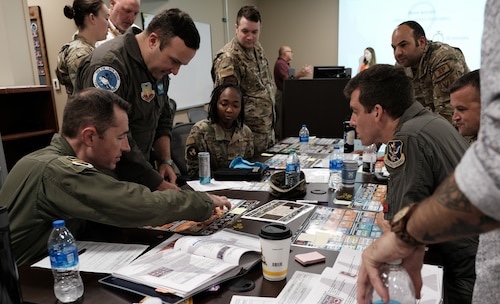

I am setting out on my last road march from Waskom Tx, to El Paso TX in an effort to raise awareness for other veterans suffering from Gulf War syndrome and to gain the attention of our state congress and senators to press forward with legislation to force the Veteran’s administration to recognize Gulf War Syndrome as a disability and all of its symptoms.

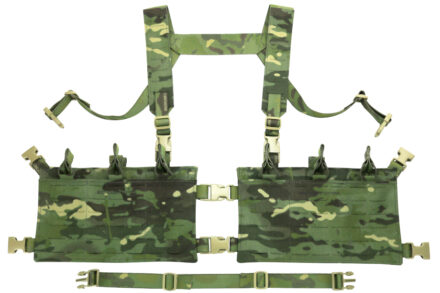

I am humbly requesting your assistance in this endeavor. I will need financial support on the road march to El Paso, TX. This a planned, 6O day walk with military backpack (rucksack or ruck) and I am asking that you go the distance with me and sponsor me by the miles walked for the Gulf War Syndrome Research at UT Southwestern, in Dallas, TX. Any amount will provide hope for this and other broken warriors!

All funds are to be directed to the Col. Bill Davis fund at engage.utsouthwestern.edu/donate-vets. If you wish to support me personally, please present all donations to my wife Lisa Mumby. Her contact info is 903-975-3144

Thank you in advance for your support and donations to finding a cure.

John Mumby

Disabled Veteran, US Army

PO Box 1102

Winnsboro, TX 75494

////

Date: 26 SEP 2022

Logistical Support for Ruck March

Needs:

Meal Ready to Eat 28 ea $12.00 ea 336.00

Mileage Pledge $_______ Per Mile

Donation Amount $______

This letter of contribution from _________________________________________________

Is to support John Mumby in raising awareness for Gulf War Syndrome

And his Road March endeavor across the state of Texas.

Date: /— Originally Signed –/

John Mumby