This article is about how to light a fire. Of course, as is my habit, I will meander a bit on the way to the final objective for this Wisdom Walk. The last week of February, I got the opportunity to do something that was both enjoyable and personally rewarding. I was invited to engage with some motivated young EOD members of the Air National Guard (ANG) at an ANG facility in Portland, Oregon. They had gathered in Portland from EOD Detachments as far away as Vermont and Texas for a colloquium, i.e., a series of seminars focused on professionally developing the junior airmen who had the opportunity to participate. My role, over a couple of days, involved facilitating some small group discussions on leadership and team building. We talked about issues relevant to them and their individual detachments and I told a few (hopefully) illustrative war stories to prompt additional thought and discussion.

Most of the attendees were E-4s becoming eligible for E-5, with 2-3 years’ time in service, and in their mid-20s. Some were full-time and others part-time. A couple had prior service in non-EOD specialties in the Army and USMC. Generally, they were not at all confident that the Air Forces’ NCOES system for their grade was adequately preparing them for leadership positions. Therefore, all the Airmen came willing and eager to learn. To their credit, the EOD organizational leadership had authorized and funded the colloquium – and perhaps subsequent iterations – to formally address at least some of the perceived gaps in their training. From my perspective, everyone involved from leadership to the most junior attendee was switched on and dedicated to the mission. By the way, the NCO who did the bulk of the leg work to put it together and then executed the plan was a Technical Sergeant (E-6). It was top-down supported, but not top driven. That is a good way of doing business. A worthy effort by all to light some leadership fires.

I did get off to a less than stellar start on my first day. Those of us not from Portland stayed at the same hotel near the ANG facility. I shuttled with some of the others in a rental SUV to the base. Because I was the oldest – by a wide margin – they let me ride in the front passenger seat. We all passed our IDs to the driver so that he could show them at the gate. Since I retired, I visit a military base about once or twice a year and normally drive my own car. Frankly, since I was a passenger this time, I was sightseeing and not paying attention or thinking about protocol. I was the only officer in the car and when the ANG gate guard saw my ID he saluted – and I missed it. As we pulled away, one of the guys said something about it and I immediately realized my mistake. I asked the driver to turn around and we circled out and back into the gate so that I could apologize to the Airman on duty and render a proper salute.

I was embarrassed by the unforced error. However, in hindsight, making the extra effort to correct my unintentional mistake perhaps served as a better leadership lesson than if I had done it right the first time. One does not get respect without giving respect. The various seminars that the Airmen attended and the small group discussions I already mentioned were not the entirety of the program. Additionally, they had daily homework which involved readings and informal briefbacks to the group and debate on various subjects. I sat in and observed many of those and, again, was impressed that everyone seemed to be putting in the work. I met briefly with the Squadron Commander who was hosting the event and had the opportunity for one-on-one sidebars with some of the senior NCOs on site. I learned a lot.

I did have an issue with one of the books on their reading list. It was, “On Combat” by LTC(R) David Grossman. This is as good a time as any to share my unfavorable opinion of this particular officer and his books. I served with 2LT Grossman in A Company, 2nd Battalion, 47th Infantry, 9th Infantry Division, Fort Lewis, Washington in 1979-80. He was my Company’s Executive Officer and I was a Sergeant (E-5). The silly SOB once tried to put me in for an (undeserved) ARTICLE-15 (Non-Judicial Punishment). Long story short, I had ample reason not to like the guy. Sometimes new leaders will try hard to be “nice” to their subordinates. Rationalizing, I suppose, that appeasement is the quickest way to get the respect they know that is needed to successfully function as leaders. That is a rookie mistake. Soldiers will take advantage of the “nice” leader but will never respect or have real confidence in his or her leadership. It is a cliché but true, soldiers respect leaders they see as “tough but fair.” Soldiers know that “nice” will not cut it when a mission goes off the rails. Of course, some leaders do the opposite. They imagine they will get respect by being dicks to their subordinate leaders and soldiers. That is also a rookie mistake, but that is the way 2LT Grossman decided he wanted to go.

So, I have a very poor opinion of the guy’s leadership skills in 79-80. To be sure, even leaders who start off on the wrong foot can evolve and improve over time. I never served with him again, and for all I know he got better with age. Maybe. Either way, that is not why I find his books problematic. His first was “On Killing” published in 1995 and apparently based on his doctoral thesis in psychology. For those that have not read it, “On Killing” beats two points to death – no pun intended. One, that humans have a powerful and innate inhibition against killing. Two, that modern military training uses “Pavlovian and operant conditioning” to overcome this allegedly “instinctive aversion” to killing. Moreover, Grossman extrapolated that violent movies and video games were doing the same thing to the youth of the world. The book did not get much attention initially. Then the Columbine School shooting happened in April 1999. Suddenly, in the post mass shooting hysteria, Grossman was a hot commodity and on all the TV shows. He was able to conveniently provide the answer that people wanted to hear. It was not bad parenting, drugs, or simply two demented teenagers who were responsible for their own heinous actions. It was violent movies and video games that were to blame for the shooting. His book sales soared.

Indeed, Grossman continued to repeat his two core assertions over and over again – in all his books. Nevertheless, they are not true nor are they supported by any real scientifically valid data or by the entirety of human history. In fact, the vast preponderance of evidence tends to prove the exact opposite. Humans instinctively averse to killing? Tell that to Cain or Able. Anyone who believes that has not had much contact with homo sapiens or read “Lord of The Flies.” I do not need a doctorate in psychology to have observed that humans kill for any and every imaginable reason – and for no reason at all. I spent some time in 1997 in Liberia. That country was at the end of a twelve-year civil war. One of the signature features of that brutal conflict was gangs of teenage boys roaming the streets hacking their neighbors to death with machetes. They had guns, but liked inflicting maximum pain and terror and enjoyed the kill more when it was slow. These boys had never seen a violent movie, or TV, or video game. Most had never lived in a house with electricity. We had run-ins with quite a few of these misguided “children.” They avoided direct confrontation with us – because they were not suicidal – but continued to terrorize the civilians out of our sight.

I have seen similar albeit less egregious examples in many undeveloped places in the world. Adolescent humans, especially males, are amoral at best. Without proper socialization, supervision, and reinforcement, they are dangerous, undisciplined, and vicious predators. More than that, Grossman claimed in his first book that almost every country in the world was experiencing a surge in violence – especially among teenagers – that was fueled entirely by those evil video games. Wrong. His earnest assertions notwithstanding, even in the 90s, despite high profile events like Columbine, violent crime was – and continued – declining in most developed countries. That is still true today. No matter how realistic the graphics, video games do not cause people to kill. Remember, Grossman also claims that first-person “shooter games” are so dangerous to a young person’s psyche because they virtually replicate the military’s insidious “Pavlovian conditioning.” That is news to me. I have personally trained hundreds of soldiers in shooting and other combat skills. I have routinely applied realistic practical application drills and repetition but I have never used – or seen anyone else use – any “brainwashing” techniques. My mission was to train soldiers not psychos. Grossman knows better and his insinuation about military – and police – training is inaccurate, insulting, and dangerous.

If bellowing out “To Kill, Drill Sergeant” when the NCO in the Round Brown asks “What’s the spirit of the bayonet” during bayonet drills is all it takes to suppress this supposedly deeply ingrained aversion to killing, I would suggest that is further evidence that it was not much of an inhibition in the first place. The American people need not worry. Military training is not going to turn little Jonny and Sally into psychologically damaged killing machines. I have already given this guy more oxygen than I would prefer. But it irks me personally and professionally that these books are still on so many reading lists and taken by some as gospel. I could continue to deconstruct his writings point by point. Many of his other dubious claims – presented as facts – are easily refuted, as are the cherry-picked anecdotal vignettes he provides as “evidence” to support his arguments. However, there are a number of other sources online who already do that debunking in more detail for those interested. Are there any “truths” in his books at all? Sure, there are kernels of valid insight here and there – mostly repeated from earlier writers. But those nuggets are buried deep in the BS that I already described. In my opinion, they are not worth digging out of the surrounding crap.

Since I always try to do my due diligent research for these articles, I did something I never intended to do. I bought Grossman’s “On Killing” and “On Combat” so I could refresh my memory. I looked at them and they were as grossly misleading as I remembered. Now, because I am loath to put them in my bookshelf with better books, I have them sitting on my desk and they annoy me. As a matter of principle, I do not believe in banning or burning books. Nor, in good conscience, could I pass these to someone else. However, if I ever have an emergency and need to start a fire, I will not hesitate to sacrifice these books as tinder for that fire. I do not think that would subtract anything significant from the sum total of humanities’ knowledge. It is probably the most utility I can expect to get from them. I trust that I have explained in sufficient detail why I would never recommend any of Grossman’s books for professional development. Still, I am not trying to make it my business to tell people what to read or not read. Consequently, I intend for this “public service warning” to serve only to more fully inform potential future readers of Grossman’s books.

Now, let us wade out of the swamp and back onto the trail. I would like to more directly address the subject of starting fires. I use fire as a tool a lot here on the Homestead. There is rarely a week that goes by that I am not starting one to burn debris. Just before my trip to Portland, we had an ice storm here. The ice brought down several trees and big branches all over my property. I have already cleared some of the stuff that was in the way, but it will be late in the summer before I get everything cleaned up. Once I get it chainsawed down to a size I can move, I carry or drag it all into an open area to burn. I prefer not to use accelerants like gasoline or fancy fire-starting techniques. I find that a crumpled local newspaper and a Bic lighter gets the job done just fine. I have been trained on a lot of methods to start a fire. I exercise some of those skills – like using flint and steel – from time to time to stay in practice but use the more expedient modern methods to get real work done.

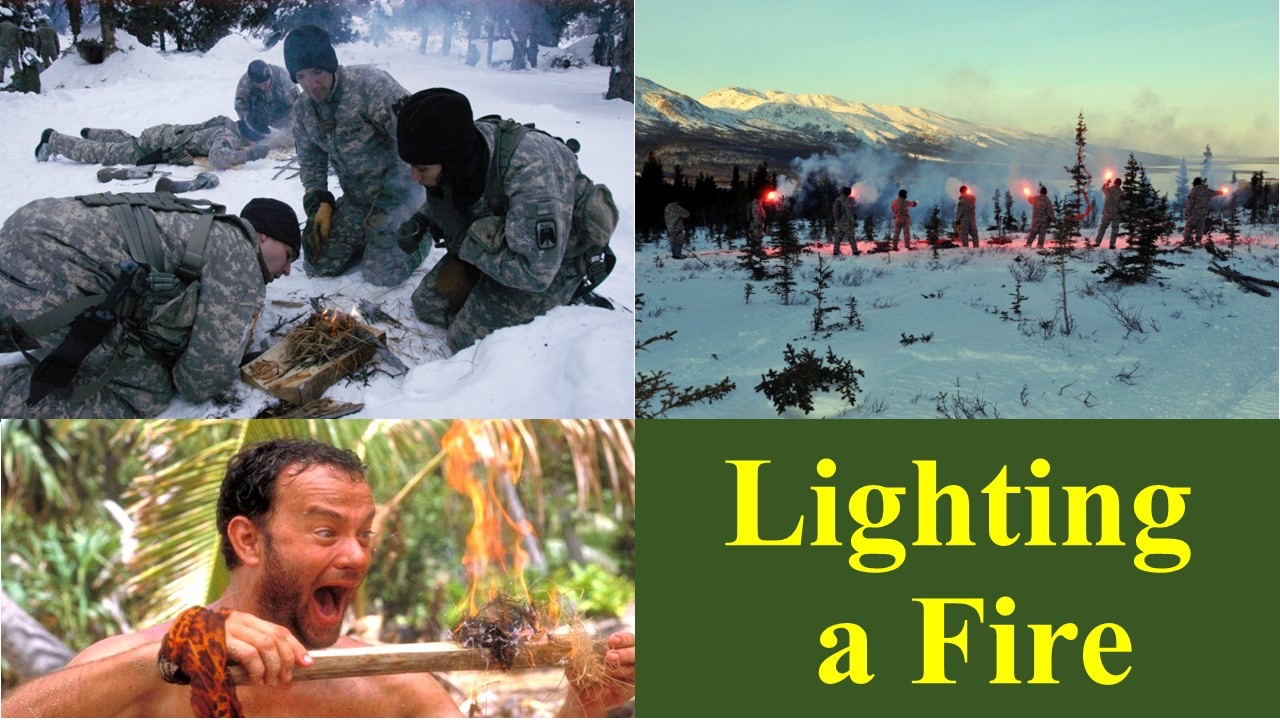

Starting a fire with flint and steel is a neat trick of the trade. It is common practice in survival training to start by introducing this technique first. If I am giving a class, I do the same. It is a confidence builder because the student is rightly impressed that two inherently non-flammable items can produce sparks when struck together. Of course, a spark only lasts a split second – not long enough to actually start a fire. Therefore, it is necessary to capture those sparks on intermediate material like charcloth to produce an ember that will last longer. The ember is transferred to a loose tinder bundle, – a birds’ nest works well – the instructor blows gently into the bundle to introduce more oxygen, and the nest bursts into flames! The flaming nest is transferred under some pre-arranged dry kindling and voila, a fire has been started. There are countless videos on YouTube demonstrating how to use flint and steel and other “primitive” fire starting methods. Of course, in real-life survival situations, flint and steel is sort of the throwaway course of action. Traditional flint and steel are not included in any military survival kits and only someone with training who intentionally wants to go “old school” would even consider those items for everyday carry vice matches or a lighter.

It is probably obvious by now where I am going with this. I truly appreciate the art of making real fire, but I am much more fascinated by the more challenging process of “lighting a fire” in a soldier’s head and heart that eventually – with luck – turns a follower into a leader. I am not talking about motivating a soldier to get the assigned task of the day accomplished. That is different. It is considerably easier to get someone to DO something than it is to get someone to BE something new, i.e., becoming a leader themselves. After Portland, I started giving it some serious thought. At first, it seemed logical to me that starting a fire in the way I described above was directly analogous to inspiring an individual to lead. The premise seemed straightforward enough. An experienced leader provides a spark, magically the spark becomes the ember, the ember becomes a flame, and a new leader is produced. However, the more I thought about my own experiences, the more I realized that I had never seen it work exactly that way. First, a proverbial spark or two from one leader is not enough. Soldiers are not necessarily predisposed to be fire-ready charcloth, tinder, or kindling. Nor, can they simply internalize a spark by osmosis, self-generate an ember, then a flame, without additional outside heat and pressure being applied.

It eventually came to me that a more accurate analogy is that soldiers are like lumps of coal. I grew up with coal fires. Most people reading this probably never used coal to heat their homes or cook their food like we did when I was young. Even before electricity and natural gas were available options for heating, coal was only accessible in certain limited areas of the country – like the hills of Eastern Kentucky. Therefore, most people alive today have only experience with burning wood in their fireplaces – if at all. Coal is funny stuff. It is not easily combustible. Sparks could shower on it all day and nothing happens. You can hold the flame of your trusty Bic on a piece of coal until your hand gets tired and it still does not light. It takes more direct heat for a longer period of time. So, to burn coal, one has to start a hot wood fire first and only then throw in a couple lumps of coal. Once the coal ignites there is no need for additional wood unless the ashes go cold and you have to start over. The coal burns hotter than wood and is not consumed as fast so the fire does not have to be refueled as often. If you have used charcoal briquettes that are not pre-infused with lighter fluid in your grill you might have some idea how hard it is to work with coal. In other words, one does not start a fire with coal. The fire has to come first.

That means that a leader cannot get by just producing sparks, embers, or small flames. A leader has to have a full-on leadership coal fire in his or her belly first. A leader, in direct proximity, has to provide enough heat and pressure to get a subordinate lump of coal (soldier) to ignite and burn independently. It takes time and probably multiple leaders reinforcing the process to make it happen. It is not easy. At least, when lighting an actual fire, one has the benefit of real-time feedback. Sparks, embers, and flames are visible. You can tell immediately if you are producing the results you want or not during every stage of the process. Not so with a leadership fire. Even the best new soldiers are only at entry-level and are still figuring out how to do their individual jobs right. It takes weeks or months – maybe years – for them to recognize, absorb, and internalize, more complicated leader skills.

We often talk about teaching, coaching, and mentoring, in the military almost in one breath. We practically say it as one word “teachcoachmentor” as if the three are interchangeable leader tasks. They are not. I may discuss them in greater detail at a later time. For now, suffice to say that I think of teach and coach as a mostly “push” process. The teacher or coach has knowledge that he or she is pushing down to the students and the student is generally in the receive mode. Mentoring is more of a “pull” process, with the person being mentored pulling the specific information they need from the mentor. I have found that tactical level leaders are fairly effective at providing push (teaching and coaching style) support, training, and guidance to their subordinates. Mentoring, not so much. Additionally, a subordinate may or may not be comfortable trying to reverse the normal dynamic and take the lead to pull information from his supervisor. That is why I recommend soldiers seek to find mentors outside their chain of command. There is just too much baggage between a soldier and his immediate leadership to overcome.

That is also why command directives for supervisors to “professionally develop” their subordinates by mentoring them on a strict schedule never produce the desired positive results. Not to mention the inevitable follow-on tracking and reporting requirements. Real mentoring is not something that can be top driven or one size fits all. Besides, no matter how hot they are, Battalion Commanders and leaders at Brigade and higher are just too far away for their heat to reach the individual lumps of coal (paratroopers) on Ardennes Street. Too far away to pass on that leadership fire. It is Sergeant’s business. It is Company Grade Officer’s business. It has to be done by hand on an individual basis. That does not mean that senior leaders do not have a role. One thing that all leaders can do is set the right example. Remember that a leader is always on parade. Be the best possible role model you can be for your subordinates. Do not try to be nice and avoid being a dick. Make an honest effort to earn respect. Do it right. You are being watched.

In fact, reflecting on my experience, I realize that I got my fire by watching leaders I respected and had the privilege of getting close to over many years. I observed intently their daily successes – and occasional failures – as they strove to achieve mastery of the art and science of war and displayed sincere dedication to principled leadership. I followed in their footsteps as best I could and hopefully provided enough heat of my own to light other fires and pass the torch of leadership successfully to those that followed me. That is the point of this article, and that was the intent of the colloquium. We will not really know if any of our efforts worked until sometime in the future when those E-4s become NCOs and we find out if the fire in their bellies is hot enough to ignite the generation of EOD Airmen coming on their heels. That is when we will have our Tom Hanks happy moment and know that we have done our part to perpetuate a fire that endures.

De Oppresso Liber!

LTC Terry Baldwin, US Army (Ret) served on active duty from 1975-2011 in various Infantry and Special Forces assignments. SSD is blessed to have him as both reader and contributor.